The Levee by Sohrab Hura

This body of work made in the Mississippi Delta saw Sohrab Hura reckoning with his own history, as curator Nathaniel Stein writes

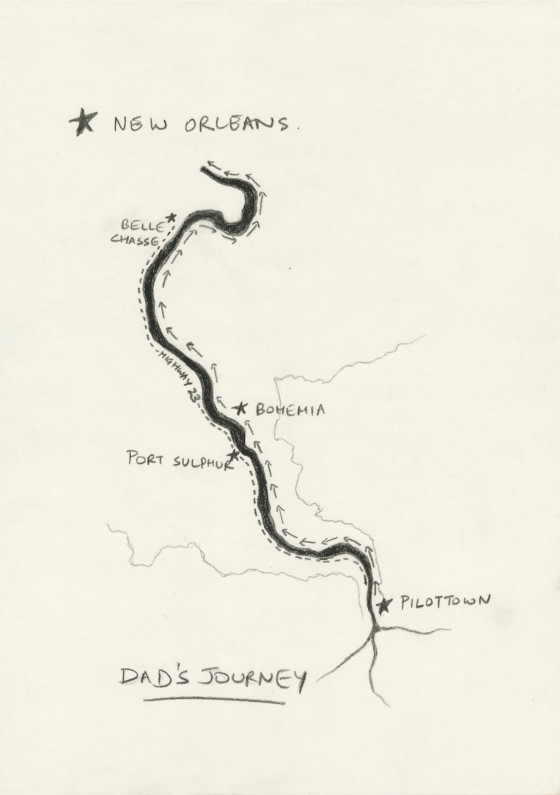

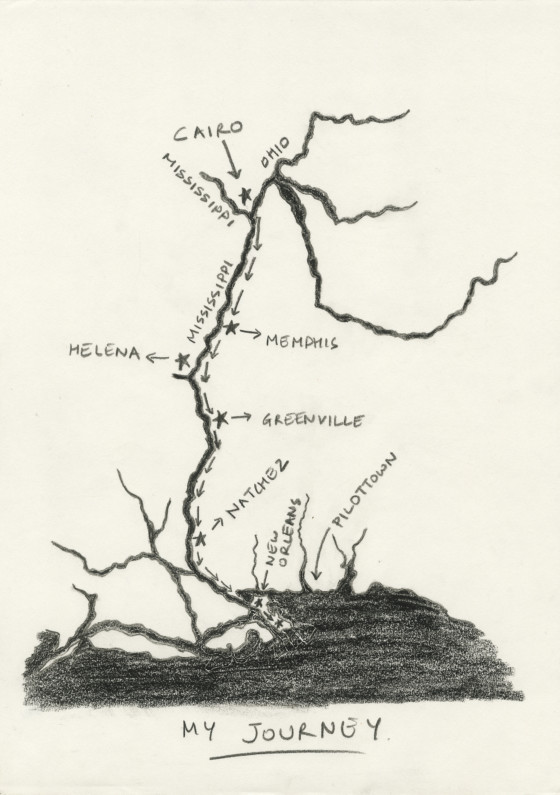

The Levee is a project by Sohrab Hura that was formed from a series of road trips made by Magnum photographers around the United States from the years 2011 to 2017. Hura, who is based in India, built his individual exploration around communities and landscapes along the lower Mississippi. The project is inspired by an appeal by the photographer’s father — who previously travelled to the river, but never stepped foot on the shore — for his son to document “what’s beyond the levee”.

In conjunction with the exhibition which displayed at the Cincinnati Art Museum from October 2019 to February 2020, the show’s curator Nathaniel Stein wrote an introductory essay for a catalogue of the works, published by the museum and titled The Levee: A Photographer in the American South. Below, you can read excerpts from the essay.

Signed copies of The Levee, the book published by Hura’s own imprint, Ugly Dog Books, are available to buy on the Magnum Shop here.

It’s April 2016. Sohrab Hura packs his camera and boards a flight from his home in New Delhi, India, to New York. In the two years since his nomination to Magnum Photos, his attention has flowed between bodies of work including one about his relationship with his mother as they live through her mental illness and one in which, partially inspired by the writings of Gabriel García Márquez, he evokes the searing delirium of summer in a central Indian village. But this latest current is sweeping him into an improvisational documentary project halfway around the world: Hura is flying to the US to join a handful of esteemed photographers on a road trip along the lower Mississippi.

The itinerary is timely; the South is much in the news. A divisive presidential primary has tapped anger among a so-called forgotten majority and North Carolina’s public bathrooms are active fronts in an American culture war. Soon, a gunman will mow down revelers in a gay nightclub in Florida. Come August, historic flooding will inundate the parishes of southern Louisiana. After meeting in Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio River flows into the Mississippi, the photographers will follow the Father of Waters to the thin fingers of its delta, finding their own perspectives on a complicated world from the shared nuclei of meals and car rides. They do not know, but will realize near New Orleans, that despite living and working in India Hura is personally connected to the Mississippi. His father—with whom the artist has a complicated, stilted relationship—has just been on the river captaining a cargo vessel. But water moves, as do all things on it. By the time Hura is on the river’s shore the vessel is already gone, and the levee is only as close as he can get to where his father no longer is. For Hura, as for many of those on the trip, tenderness is the emotional keynote. The times are raw, full of pain and gentleness.

The Mississippi Delta trip is the last of ten organized under the umbrella of Postcards from America, a loose collaboration conceived in 2011 by photographers including Alec Soth and Jim Goldberg and writer Chris Klatell. Prior journeys have taken participating artists to places like the Southwest; Florida; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Rochester, New York. The idea is to experiment with visual polyphony, to push through the inhibiting weight of representational politics and cliché, break out of ingrained photographic habits, and see what happens.[1] At the same time, by taking to the road to picture neglected quarters of America, the Postcards endeavor echoes photographic touchstones ranging from Depression-era documentary to Robert Frank’s The Americans to Soth’s own Sleeping by the Mississippi.[2]

In its six years of existence, Postcards has framed important questions about documentary photography and fostered rich reflections on contemporary American life. Yet the body of work that comes from Hura’s time along the Mississippi is not a documentary account of a particular social issue or political event, not a position on the Deep South, but the sense Hura makes of his experience there. Like his work in other contexts, The Levee is a response to an encounter, in which the photographer embraces an unfolding interplay of emotion, intuition and point of view. In fact, it is not until he reaches the delta that he fully understands why he is making pictures at all.

[ … ]

Although he was cognizant of his father from the beginning of his own journey, it was on the way to Pilottown and during solitary time spent on the deep delta afterward that Hura fully connected the tenderness he perceived in the world along the lower Mississippi to the tender experience unfolding within himself. Thus when he writes [in his artist statement] of Pilottown “it was here that the river opened into the sea,” it is not merely a description of the place on the map where he reached his father’s landfall, but a reference to a painful opening in his own awareness. Many of the pictures that make up The Levee came after this breaking point. Broadly stated, in The Levee Hura registers what he observed along the river in light of and through his parallel emotional journey. Tenderness was the point of contact between two realities: the outside world and the interior life through which it is inevitably seen.

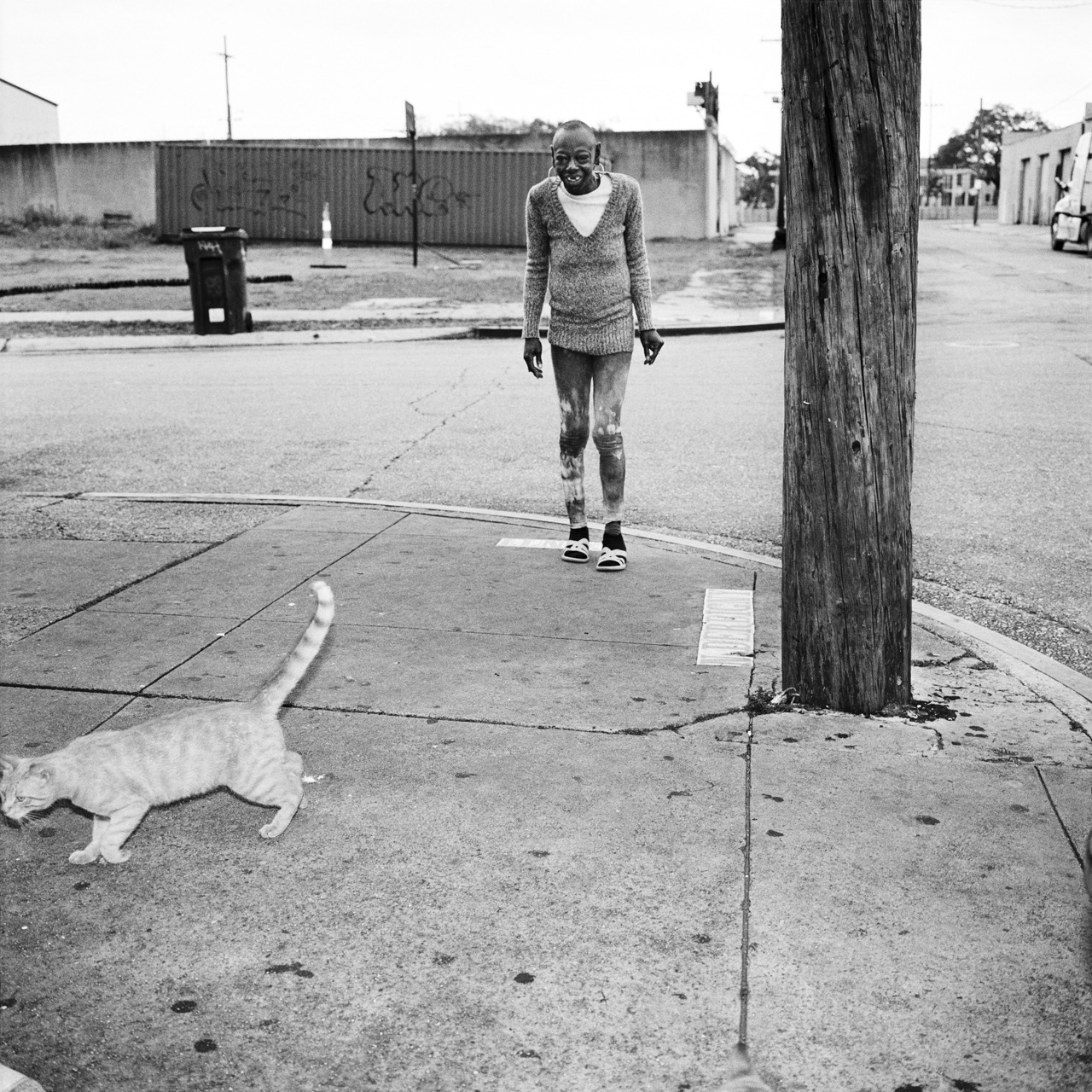

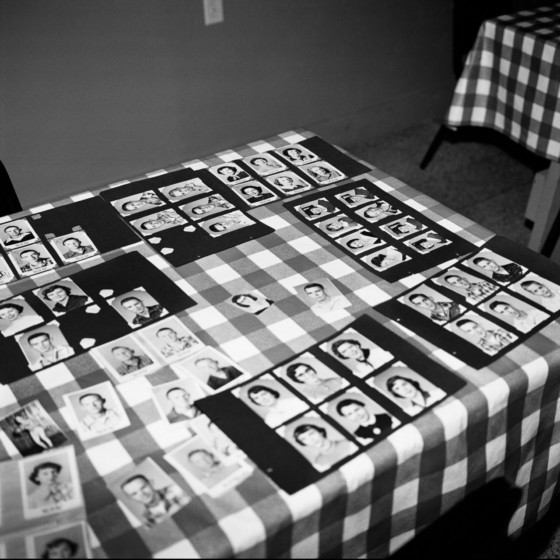

Broadly speaking The Levee consists of portrait and landscape photographs, in which intuitive composition conveys the unstaged, stream-of-experience character of Hura’s impressions. Overall the suite portrays complex human relationships in an environment with a long, continuing story of unresolved beauty and pain. Sequencing and spatial relationships among pictures have varied across presentations.[3] Yet, although there is no single authoritative layout, the images do create different inflections within the whole depending on how they are organized. To identify some navigation points: an opening group of six images has remained relatively constant. These touch on subjects, symbols, and feelings that structure the suite—the aching grace of the weeping willow, a young man bearing a burden, a lone bird on a branch, a woman on her threshold, domestic and natural spaces that suggest violent disruption, whether from social causes or the force of the river when it overflows. There is also a group of images that usually cluster toward the end of the suite. These reflect Hura’s geographical progress toward the far delta, but just as importantly, they include increasingly poignant allusions to the nearness and unreachability of the river. Animals are significant throughout the suite, and, as Hura’s statement suggests, birds are especially important. Birds and birdhouses punctuate the work, at times appearing as surrogates for the human characters we know are in play, at times suggesting the proximity of land and river or acting as guides toward the water, and often evidencing unexpected gestures of care or kindness.

The Levee is formally and technically different from much of Hura’s prior work. It was shot with a medium format film camera rather than the 35mm, instant, disposable, and sometimes even homemade equipment Hura has used in other situations. Subjects tend to be centrally placed within the square frame of the image, and the picture plane is often closed or relatively shallow. Exposure and contrast are more balanced, and grain far less in evidence. Apart from a few significant instances almost all the photographs use standard focus—and indeed, while telling, the occasional uses of selective focus are well within the conventions of photographic composition. Overall the images of The Levee give an impression of compositional stability; they are visually straightforward, stripped-down and direct—which is not to say they are reportage, or without symbolic weight. In contrast to the panoramic, generalizing images his father could offer from the deck of a ship, Hura relates a series of specific, close-range, and consciously limited impressions from his own vantage point on land.

Hura’s understanding of The Levee’s pared-down visual language is as clear as the language itself: it is form that flows from the character of the relationship he experienced with the world around him. Indeed, one could argue that for Hura form is itself a kind of mimetic device, in which his handling of materials analogizes the specific sensibility he perceives in a setting. The beauty Hura found in the landscape of the delta (“the blues and the wetness of the land”) affected him, but so too did the unlikely optimism, earnestness and, sometimes, grace he perceived in the people he encountered. The photographs of The Levee are comparatively gentler than much of his previous work by being quieter, more formal, and more whole. They register the sense of directness the artist felt among the people he met along the levees. In fact he found this forthrightness “unburdening” in comparison to his experience in India, where for him “everything feels enmeshed in layers.”[4] At the same time, the relative formality of Hura’s visual language in The Levee has symbolic meaning.

In contrast to the Sweet Life trilogy, The Levee stems from an encounter with a foreign place, in which the artist knows he is photographing people enmeshed in lives he cannot fully enter or read. Some of the images express limits as literal as they are metaphorical. For example, although most people Hura encountered were open, curious about him, and willing to engage, he found that domestic spaces were inviolable. Many images in The Levee are set outdoors, in public or in liminal spaces. Architectural thresholds often appear as impenetrable boundaries. In other images, property lines, transition points between public and private space, social groupings, and even features in the landscape become barriers; Hura is close to connections among others, but he is almost always looking from a position outside.

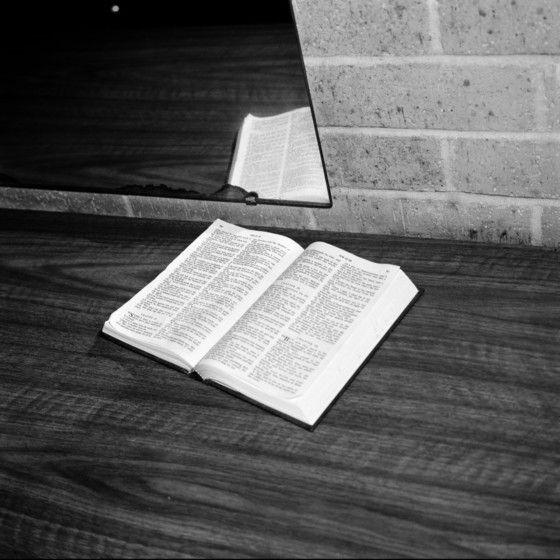

There are also images that touch on cultural difference and limits to the right to represent. One such picture depicts an open Bible on a motel room vanity. The photograph was taken at a point in Hura’s journey when he was perhaps most in the grip of his own emotions. Feeling the need to remain alone near Pilottown, he had decided to stay at a roadside motel while other members of the Postcards group returned to New Orleans. His travel companions felt uncomfortable leaving him behind there, for fear of racist or xenophobic attack.[5] The picture is a close, stark composition cut by sharp lines, in which the book is partially doubled in a mirror reflection. By contrast, another image that is often presented near the motel Bible picture depicts an African American man standing on a sidewalk, embracing himself with a Bible in hand. In white shirtsleeves and a bowtie, the man appears deeply self-possessed, rooted in front of a telephone pole. Among other things, these two pictures express the complexity of an outsider’s encounter with Christianity in the American South. Christianity is not a foreign construct to Indian observers. Though a minority faith in India, it has been observed in South Asia for centuries. Yet the history and cultural formations of Christianity in the American South are particular and complex; they can be alienating to outsiders, as even many Americans can attest. On the one hand, the motel room picture suggests a private confrontation with a faith that can have illegible or even threatening dimensions. On the other hand, the following photograph is an observation of the granular integration of faith in others’ lives—the Book as pillar, lovingly held in the context of a community.

The image of the Bible in Hura’s motel room is not inherently disrespectful, but in Hura’s estimation his making of the photograph was a transgression that resulted in a forceful rejection from the place and culture he in which was interloping.[6] It was the last photograph he made on the trip. To include the motel room picture alongside counterpoint imagery was to be forthright about a complex and contradictory experience of otherness, in which one’s own difference feels sharp amid observed connectedness and connection. In a similar way, the formal remove from which Hura seems to photograph in The Levee describes his position as an outsider to the physical and social world he is moving through. It also visualizes the other barrier he is working toward and across: the levee between himself and his father.

[1] Chris Klatell, Alec Soth, Jim Goldberg, and Christopher McCall have generously contributed to my understanding of Postcards from America through telephone and email conversations. The most helpful published source on Postcards is Jim Goldberg, Chris Klatell, and Donovan Wylie (eds.), Rochester 585/716 (New York and San Francisco: Aperture Foundation, Pier 24 Photography, and Postcards from America, 2015).

[2] Britt Salvesen has expanded upon this lineage in “American History,” in From Here to There: Alec Soth’s America, ed. Siri Enberg (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2010), 104-111. See also Geoff Dyer’s “Riverrun,” reprinted at 78-82 in the same volume.

[3] Indeed, Hura is interested in provisionality and has used revision as an artistic strategy throughout his career. At the time of writing, The Levee has been exhibited in its entirety twice. The presentation at the Cincinnati Art Museum went on view in October 2019 and a separate but related presentation at Experimenter Gallery, Kolkata opened in August 2019. The Cincinnati project was the first complete presentation of The Levee outside India and Hura’s first solo museum exhibition. The Kolkata presentation occurred within Searching for the Stars Amongst the Crescents, a group exhibition celebrating Experimenter Gallery’s tenth year. Active planning for Cincinnati began in January 2019, following several months of conversation around the museum’s acquisition of the complete body of work. Organization of the Experimenter show began later in 2019, such that Hura was able to draw on thinking already accomplished for Cincinnati. By the same token, certain installation decisions made in Kolkata fed back into late-stage planning for Cincinnati. While these exhibitions were being prepared Hura was also at work on the layout and design of The Levee photobook, published under his Ugly Dog imprint. In practice, an Experimenter Gallery PDF presentation of The Levee has acted as another distributed statement of sequencing. In addition, selected images from The Levee were on view at the FotoFest Biennial, Houston, 2018, and one image from The Levee was included in For Freedoms at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, June 7–August 30, 2016 (see discussion later in this essay). More provisionally, images that would later become part of The Levee were included in an informal pop-up show at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, on April 23, 2016. This was not an exhibition in the conventional sense, but rather an event that occurred under the rubric of public programming for another exhibition then on view at Crystal Bridges. Finally, it should be noted that works from The Levee were originally slated for inclusion in the Pier 24 exhibition This Land (June 1, 2018–April 25, 2019, San Francisco). They were dropped from the project when a section titled “When the Levee Breaks” was cut due to space constraints. Several other photographs made by artists during the 2016 Postcards trip appeared in This Land. I thank Christopher McCall for sharing information about preliminary plans for the Pier 24 exhibition.

[4] Hura, conversation with the author, January 19, 2019.

[5] Chris Klatell, telephone conversation with the author, July 30, 2019.

[6] For fuller account of events surrounding the making of this photograph, see Chris Klatell’s travel notes, reproduced later in The Levee: A Photographer in the American South.