Through the Window

Kate Simpson, of Aesthetica, explores the role that windows play across the Magnum Archives, considering the acts of looking and seeing between public and private worlds

In Susan Sontag’s seminal collection of essays, On Photography (1977), she states: “Photographs are a way of imprisoning reality…One can’t possess reality, one can possess images – one can’t possess the present, but one can possess the past.” With this in mind, all images are frameworks. They offer a version of a particular moment, as Sontag posits, that we can never really “possess” or understand in all its entirety. We can only “see” what the photographer allows us to, in the same way that we can only “perceive” that which our physical body allows.

This, of course, is part of the human condition. We cannot experience everything. We are not omnipresent, (though we may feel this way with the rise of smartphone activism, increasing connectivity and news feed algorithms providing constant updates.) In reality, we are still bound by the same physical laws. When we look at an object, the cornea acts like a window at the front of the eye – controlling the amount of light that enters the pupil. The iris acts like a muscular curtain, pulling back to allow us to make sense of an image before us.

In the same way, photography is bound to its contextual parameters – location, time, angle and camera settings. Given that all photographs exist in the past, and are ultimately self-conscious of this, what role do windows play in furthering this metaphor? How have photographers utilised the window as a way of drawing attention to the lens? How do they separate those “in” the shot, from those “outside”?

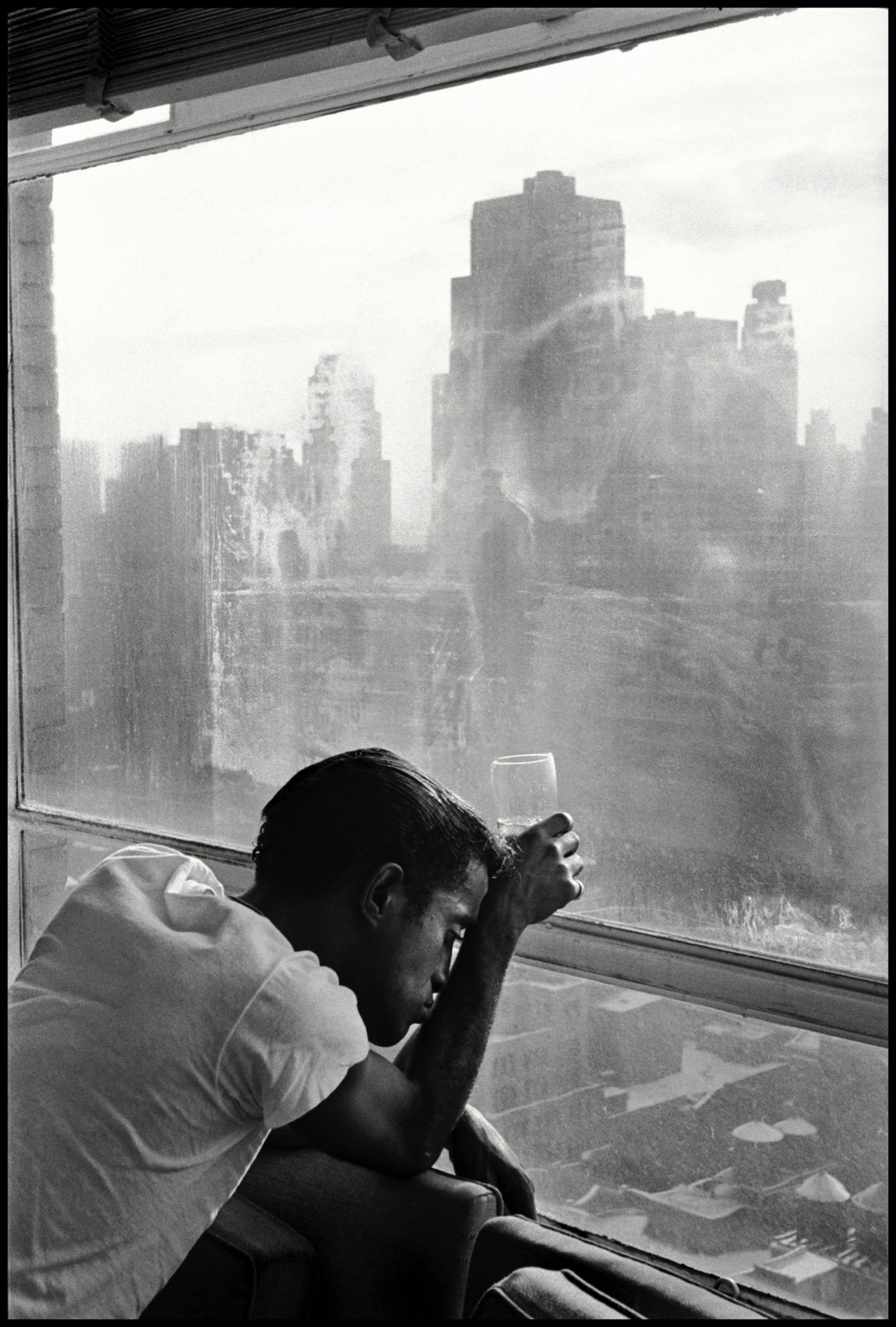

For many Magnum photographers, windows play with a sense of freedom – a concept that feels increasingly alien as we head towards a second surge of Covid-19 cases and nationwide curfews. In the works of Christopher Anderson, for example, expansive New York skylines and golden afternoon light scintillate through the panes, whilst physical gestures point towards relaxation, liberation and ease. In an image from his 2012 book, SON, legs are outstretched – dangling off the bed – one knee bent towards the sun.

In another image, a tilted head basks in the glow of another passing day. Interesting to note here is a figure who seems flippant – carefree even – as she approaches a casual flick of the hair in her home on the 86th floor of the Trump Tower. The image was taken in 2016, on the run up to the US election, and is hauntingly calm. Still, Anderson’s photograph is prophetic, capturing a cityscape that’s heading, unbeknownst, towards a new era of complete upheaval, seeming almost to revel in the last few moments of summer – of promise. To look at the image in 2020 is to see the red jumper like a flag, popping out against the pale-blue shimmer on the horizon line – a state line.

Whilst windows can be a symbol of leisure – of potential and promise – they can also denote a kind of border or boundary line, separating public from private; outside from inside. In 2019, the year before Covid-19 swept the world, Gueorgui Pinkhassov captured a figure turning away from an open window, adjusting the belt on a winter coat. The photograph is a distinct separation between that which we present to the outside world, and the moments spent inside. The figure is turned away from the light pouring through the opened shutters, preparing them-self, it seems, for a journey outdoors.

It is, perhaps, just as likely that the figure might just have returned, ready to take off their layers and unpeel into domesticity – beyond the public gaze. Pinkhassov plays with the ambiguity. Meanwhile, the figure stands directly in-between the camera in the window, closer in proximity to the lens, suggesting an intimacy that would be otherwise unlikely to strangers in the public realm. A warm orange glow bounces off the coat fabric; the sky is a cold grey. There is a sense that the figure is retreating into the security, safety and comfort of the room, changing slightly to the new location and social parameters.

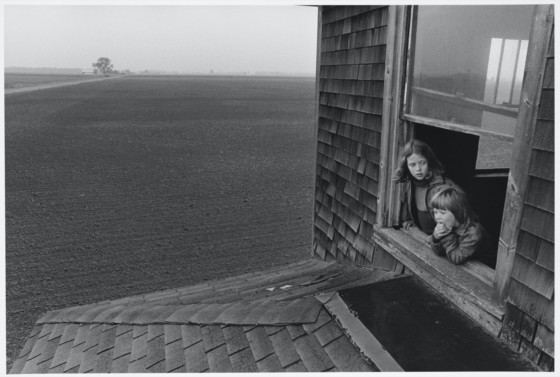

In instances where windows clearly separate inside from out, there are – again – multiple avenues for interpretation. In the works of Larry Towell and George Rodger, frames are fully opened, figures leaning out to exercise their gaze. Here, windows are like portals – allowing a further sense of connection or wonder. These structural features allow the characters to imagine and explore with their eyes. In these two examples, the figures take up less than a quarter of the images at hand, instead encouraging the viewer to look intently upon the rolling hills and sweeping landscapes. Here, the photographs marry form and subject successfully. Both Towel and Rodger replicate a sense of curiosity – the sense of potential and boundlessness felt when looking towards the horizon. As an audience, we are forced to consider the limitless of the single moment – of what the individuals might have been thinking, feeling or experiencing in the second that the shutter clicked shut.

In just as many cases, windows demonstrate disconnection – moments of retreat from the community, a sense of shutting out or being shut out. In 2017, Paolo Pellegrin accompanied two UNICEF workers as they travelled the Lake Chad region in Africa to document refugee communities after the Chadian military forced 50,000 islanders to relocate to an inhospitable mainland. In one particularly poignant example, Pellegrin photographs an individual (named Rosaline for the purposes of the investigation) who is turned away from the window, looking down at a device between her hands. The composition is intimate and mournful – the gesture forlorn as she faces into the shadows.

In the same year, Fujifilm invited Mark Power to reflect on the notion of “home” across Britain. In one image, a slumped figure leans across the desk in a moment of concentration, boredom, or perhaps even, sleep. The image connotes the idea that any of these emotions or states is possible within the confines of the home, where people take centre stage and define their own domestic reality; the individual sits directly in the middle of three windowpanes.

Beyond separating indoor and outdoor worlds, windows are often also a reminder of the lens – of the presence of the photographer, the camera, and the practice of trying to – as Sontag describes – “possess reality.” In many cases, windows are structural features that draw the eye and exemplify the construction of the image in all its intricacy and complexity. Carl De Keyzer, for example, shoots the interiors of a Moscow hotel room. The television screen shows a body in motion, which in turn sits in front of a window overlooking high rises. Here, the dialogue between movement and stasis, humanity and infrastructure, is accentuated. De Keyzer’s work is self-conscious of its own assembly line – of its own intentional fabrication. Frames sit within frames like Russian nesting dolls.

Other self-reflective examples reference the development of photography as a technological tool as well as a creative medium that continues to grow, develop and become increasingly accessible. In 1826, the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce gazed upon his studio view in Le Gras, eastern France. Niépce set up a camera obscura, which captured and projected scenes illuminated by sunlight. The scene was cast on a treated pewter plate that, after many hours, retained a copy of the buildings and rooftops outside. The result was the first known permanent photograph.

In 1997, René Burri journeyed to the same location with a print copy of the Niépce image. A woman holds it against the landscape it depicts. The concurrent photograph is meta-fictional – a hybrid between fine art and documentary. At the second it was taken, the image combined past with present, layering over 150 years of innovation, practice and craft. Compositionally, the work is cyclical, moving from landscape to window, window to viewer, viewer to camera, camera to print, and back through the whole process again. Conceptually, it assesses the nature of human perception, revisiting a landscape and re-writing the narrative. It considers history and memory, as well as inspiration and authenticity.

Burri’s image also highlights the difference between “looking” and “seeing” – the contrast between active and passive participation – as well as the viewer as voyeur. This is a constant source of investigation for almost all Magnum photographers, seen clearly in the juxtaposition of a Harry Gruyaert image taken in Gao, Mali, and a Martin Parr piece taken three years later in England. In the former, figures outside of the window remain untouched by the photographer’s gaze, unaware of its lingering presence. The frame is a way of “looking” onto a plane, where people happen to be walking, playing or talking. In the latter, the window acts as a kind of theatrical backdrop, where figures pose – plush pink against clashing red – turning away from the lens back into the room. Here, they are seeing – aware of the camera – and are seen. Plurality is rich – with the double take of (presumably) mother and daughter, alongside duplicate armchairs. There are small moments of asymmetry, though, with one pane opened on the right-hand side, and a cushion on the left-hand chair. One could read into this as a sign of maturity and “slowing down” for the figure on the left, with the promise of youth for the figure on the right. Meanwhile, the red clothing sits sharply against the greenery outdoors, which moves freely, organically, against a manicured, controlled interior.

As restrictions return across the UK, as well as the rest Europe, and we apprehensively await the outcome of the 2020 US election, it’s an interesting time to consider the distinctions between public and private, and the ways that we “see” and understand information from interior to exterior. It’s never been a better time to celebrate the power of photography as a window in itself – to understanding our position in relation to others, whilst being wary of who’s shooting and the message behind the lens.