Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Mexico

The Magnum co-founder roams the Mexico streets where he honed his signature style

Henri Cartier-Bresson was 26 when he first arrived on the shores of Mexico, having signed up for a French ethnographic mission to photograph the construction of the Pan-American Highway. But he was most drawn to Mexico, where the trend for surrealism had taken hold. This was not his first trip abroad. He’d travelled from France to Spain and Italy, and an exploratory trip to France’s African colony the Ivory Coast was cut short by blackwater fever. On each occasion, he had received little in the way of recognition or encouragement. Mexico, he decided, was to be his moment – a demonstration of what he could do with a camera.

Cartier-Bresson placed his trust in the head of the expedition to Argentina. Yet, one morning in Mexico City, he woke to find the older man had quietly left in the night, taking the group’s funds with him. Cartier-Bresson was penniless, hundreds of miles from home, and with his early photography career in tatters. The Trocadero Museum had advanced him $1,200, and wanted its money back. His fellow Frenchmen disbanded. Write to your father, he was urged. Return to Paris and start again, but Cartier-Bresson stayed.

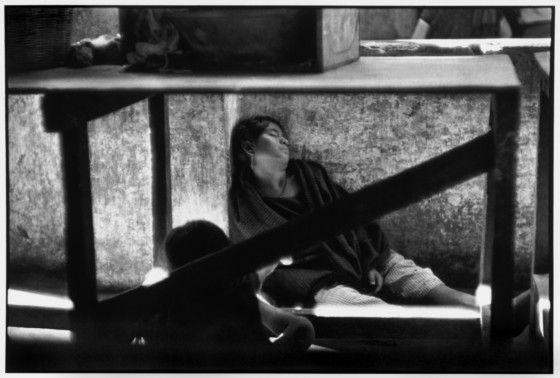

The Mexico City Cartier-Bresson began to discover had 53 different ethnic groups, each with its own heritage, language and customs. He couldn’t speak any of them. He was deeply out of place. Yet, in a cafe, he met African-American poet, novelist, and playwright Langston Hughes, from Harlem, who was then scratching a living by translating Mexican poetry for the American market. Cartier-Bresson must move into his home and meet his artist friends, Hughes declared. His home was a small hovel in la Candelaria de los Patos, a lawless hive of prostitutes, thieves and gangsters, a no-go area for the city police.

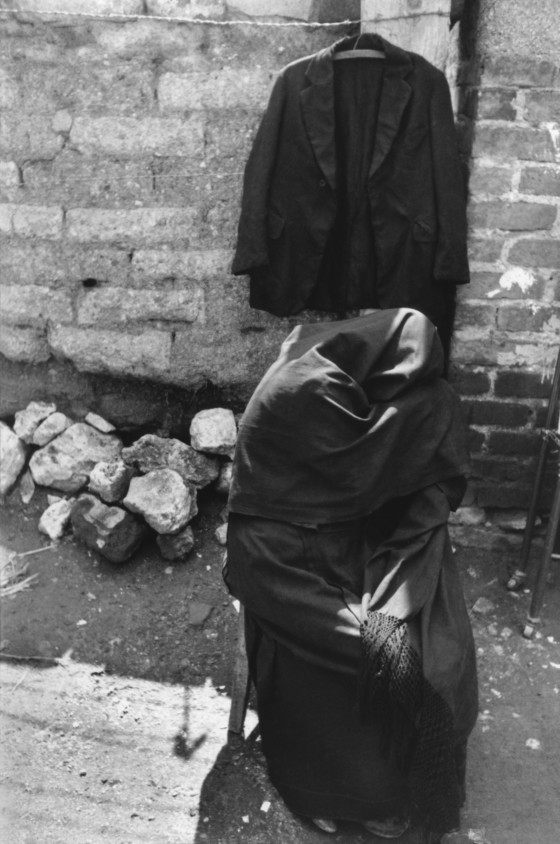

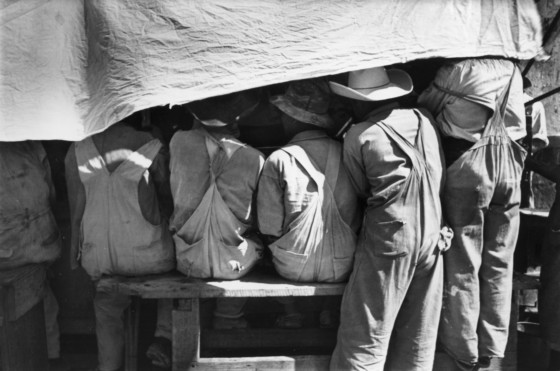

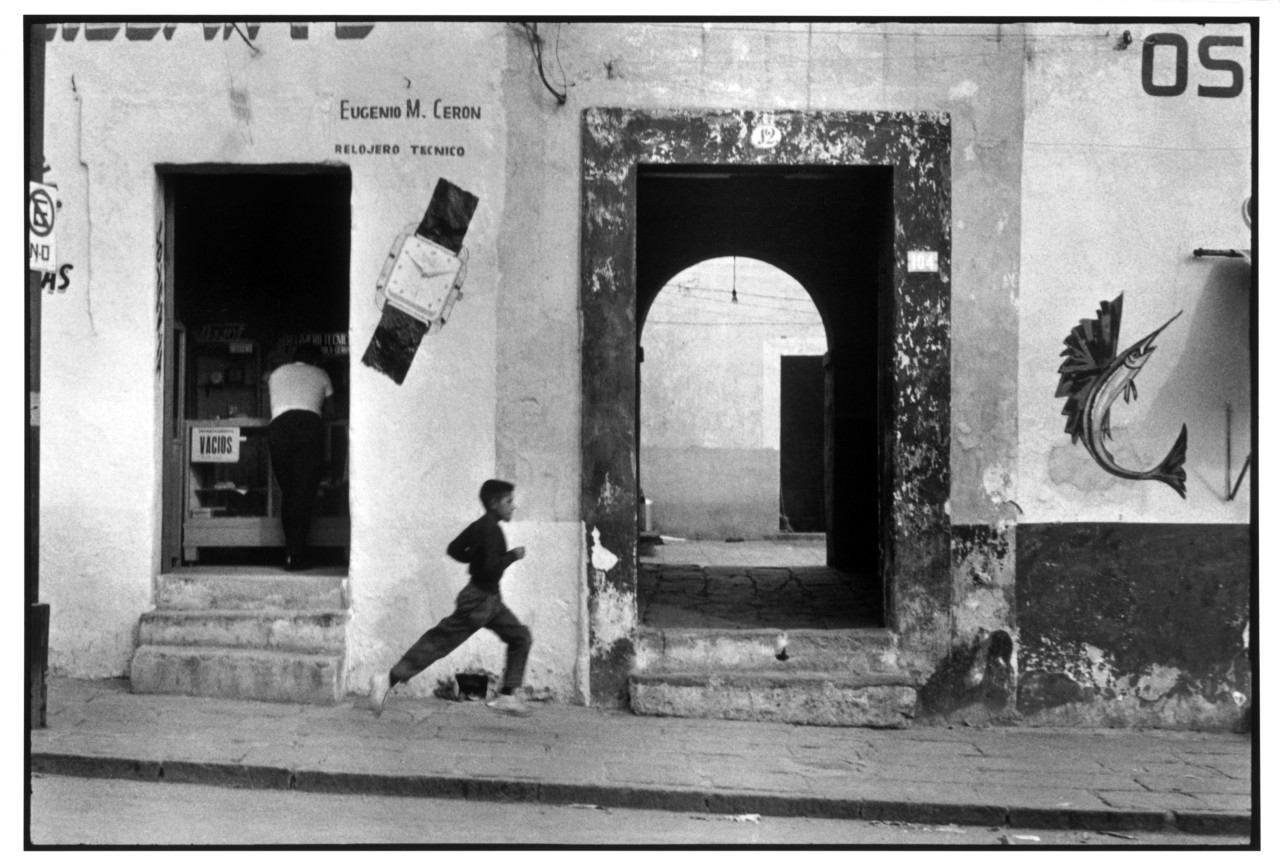

Cartier-Bresson became known locally as “the little white man with the cheeks of a shrimp.” He worked for the local press, and walked the streets of Mexico City, photographing street scenes in the long angular shadows of the afternoon sun, often from high vantage points. It was here, as he produced shots with dramatic lighting and experimental framing, that he first began to reconcile his fine-art schooling with an impulsive and intuitive eye for roaming street photography. Here was the gestation of Cartier-Bresson’s most influential idea: “Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera,” he famously later wrote.

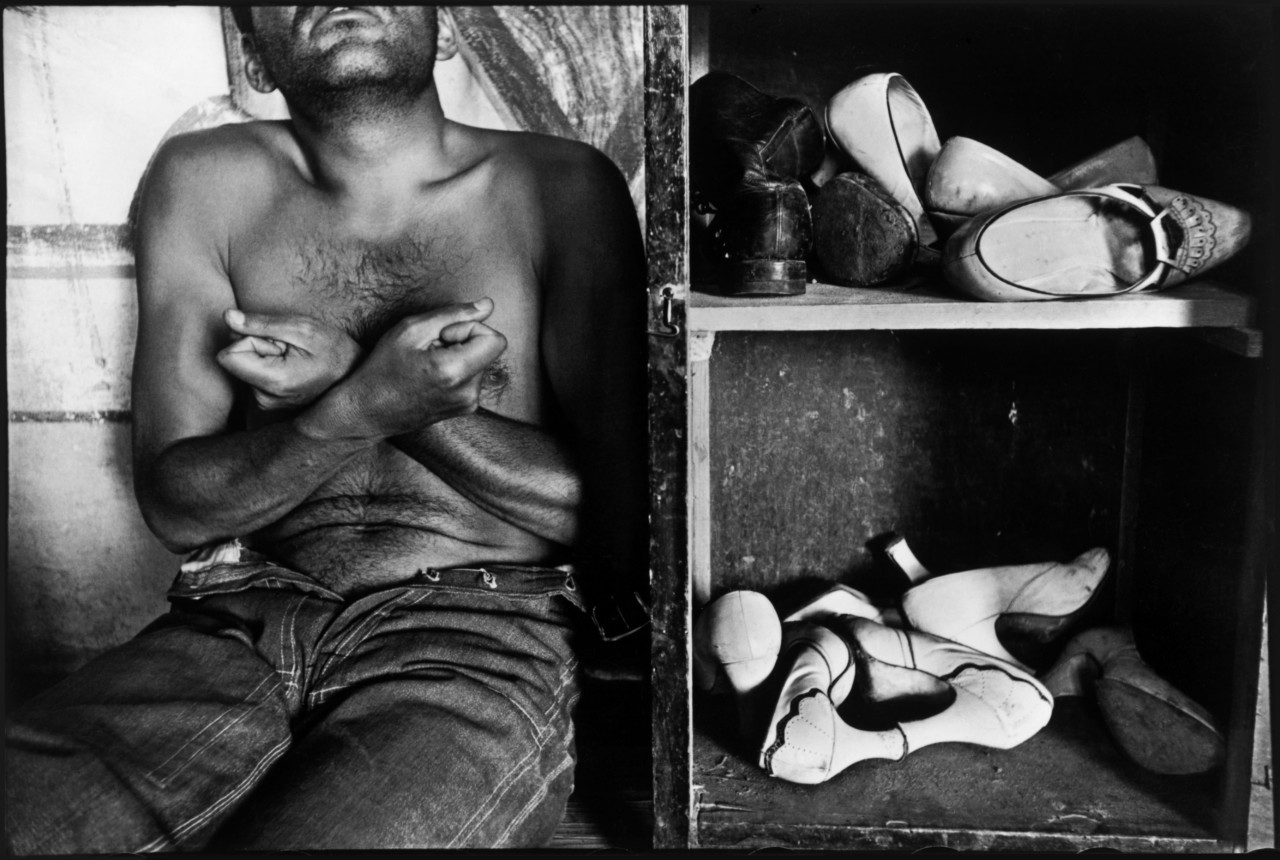

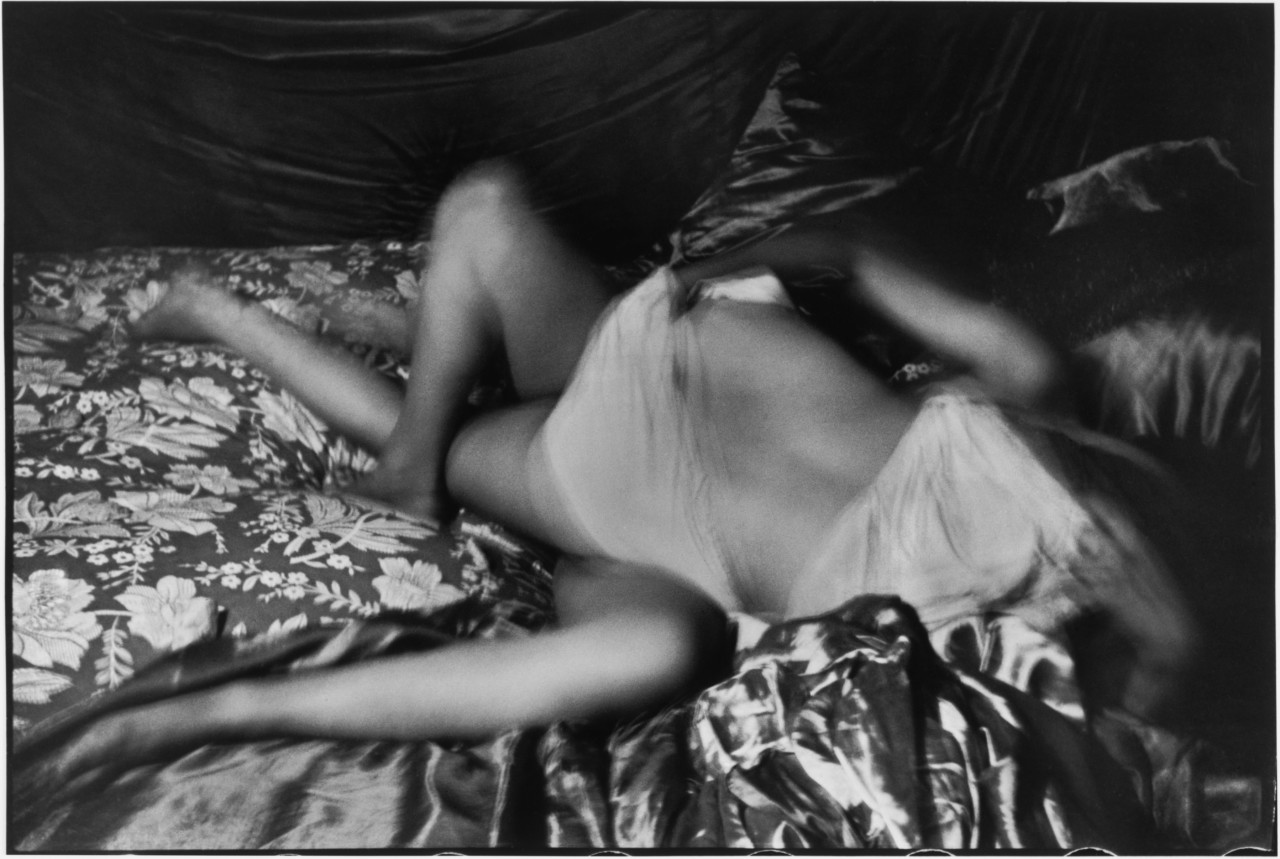

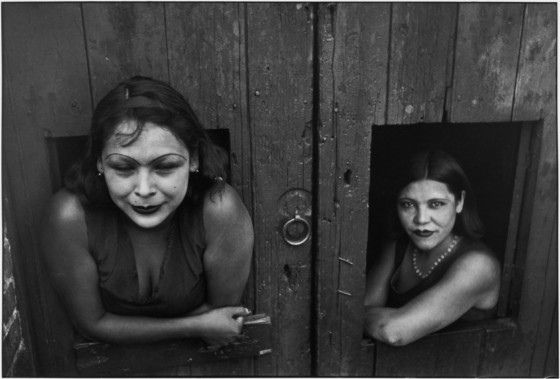

One picture, in all its serendipity, seems to capture such a syntax. Cartier-Bresson was at a local party with his new artist friends. The tequila flowed, but he remained sober. He left the party to explore the higher rooms of the building. In one room, the door ajar, he could hear two women making love. “I couldn’t see their faces. It was miraculous – physical love in all its fullness,” he later recalled. “There was nothing obscene about it,” he said.

The picture became known as ‘The Spider of Love.’ In Henri Cartier-Bresson, A Biography, Pierre Assouline writes of the picture: “It was a photo bursting with life, movement, eroticism and emotion, making an accomplice of the observer; it has duly found its way into the pantheon of Cartier-Bresson icons.”

In March 1935, Cartier-Bresson’s Mexico photography was exhibited at the Palacio de Bellas Artes with Mexican photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo. A famous New York art dealer became his benefactor. Recognition had found him.

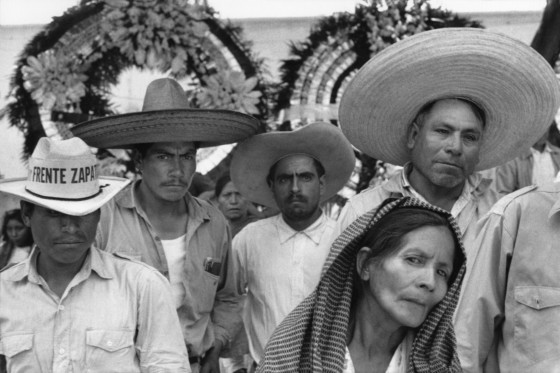

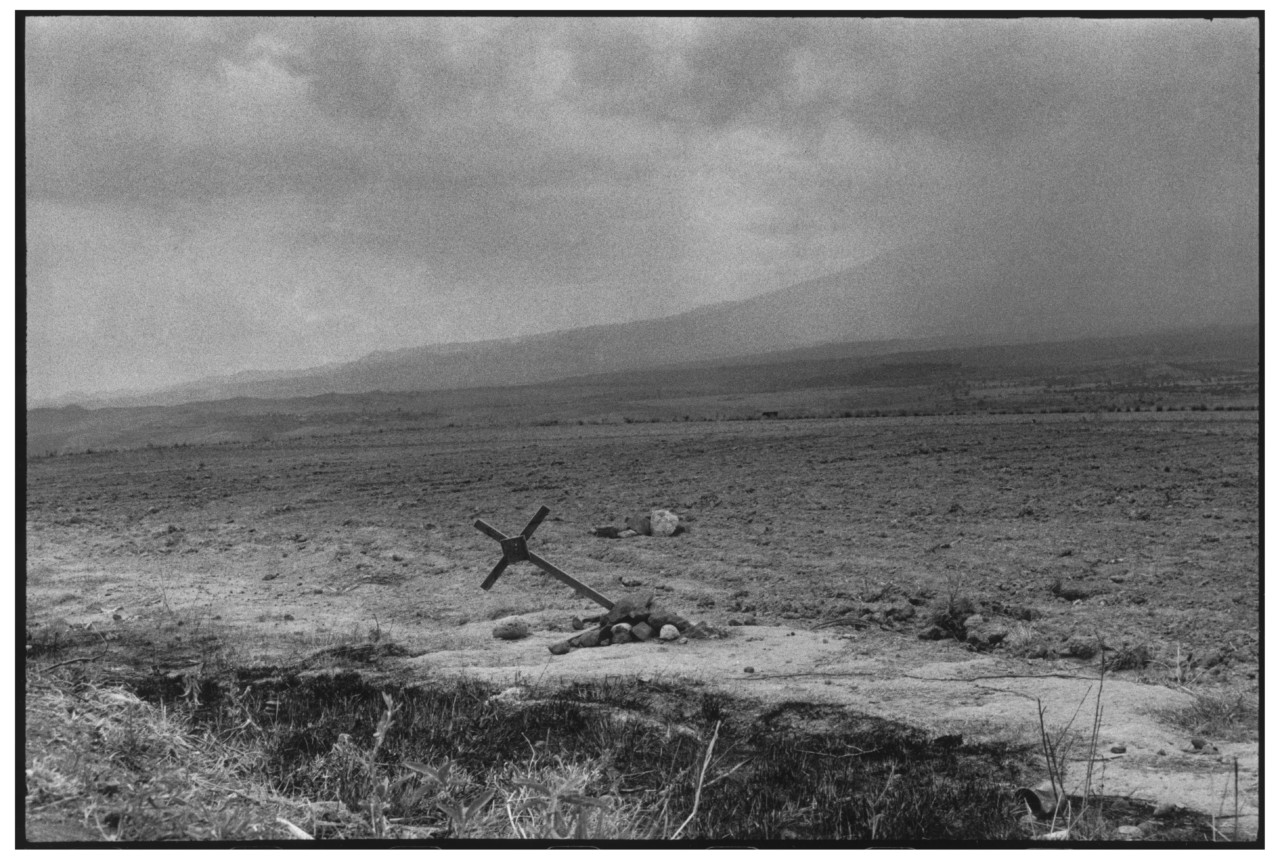

Cartier-Bresson would not return to the country for almost 30 years. The world had changed rapidly in the interim; not least the devastation of his home country caused by WWII. By the time he returned to Mexico, on commission for LIFE magazine, he was one of the most celebrated photographers in the world. His access, and means were now far greater – he photographed a black-tie reception at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, trekked to the foothills of the Popocatepetl volcano, and stood on the frontline of the anniversary celebrations of the death of Emiliano Zapata, the Mexican Revolutionary.

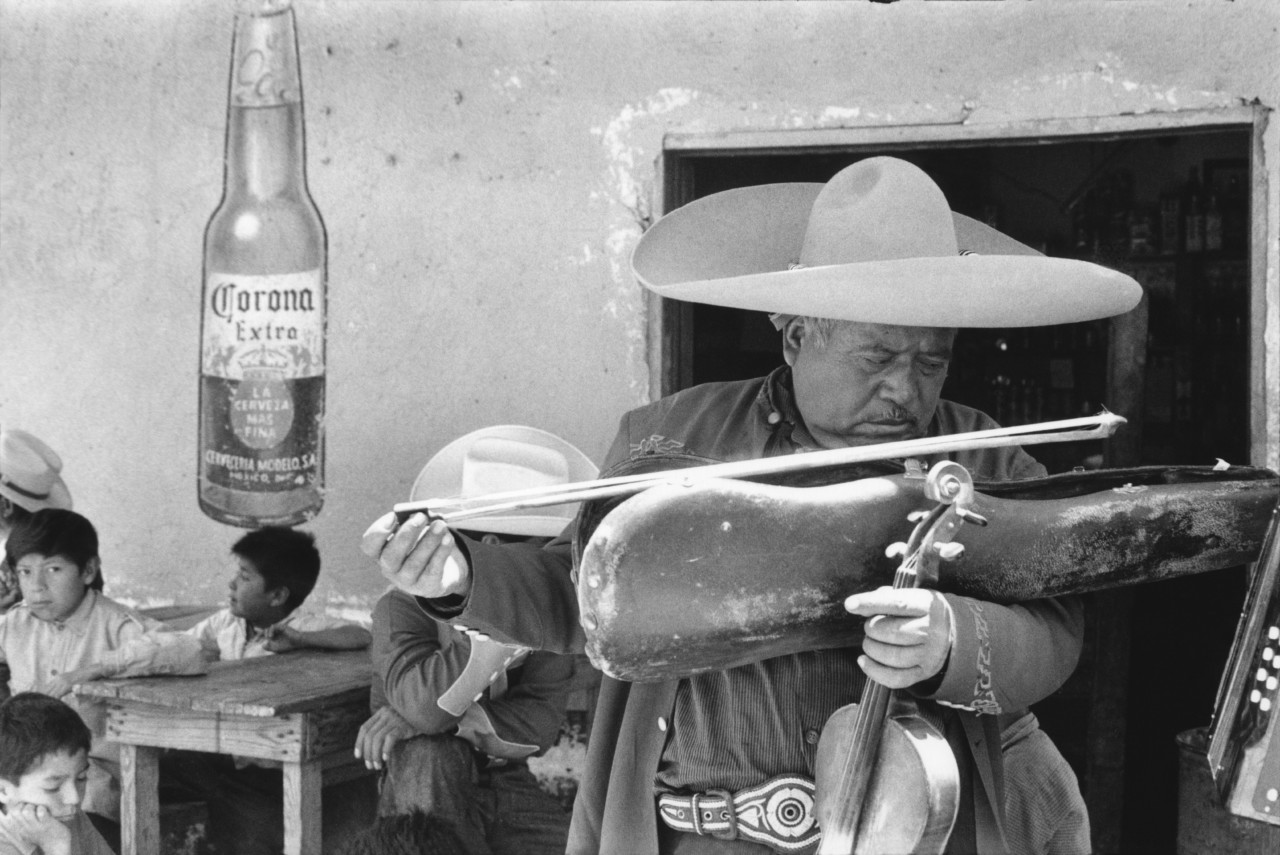

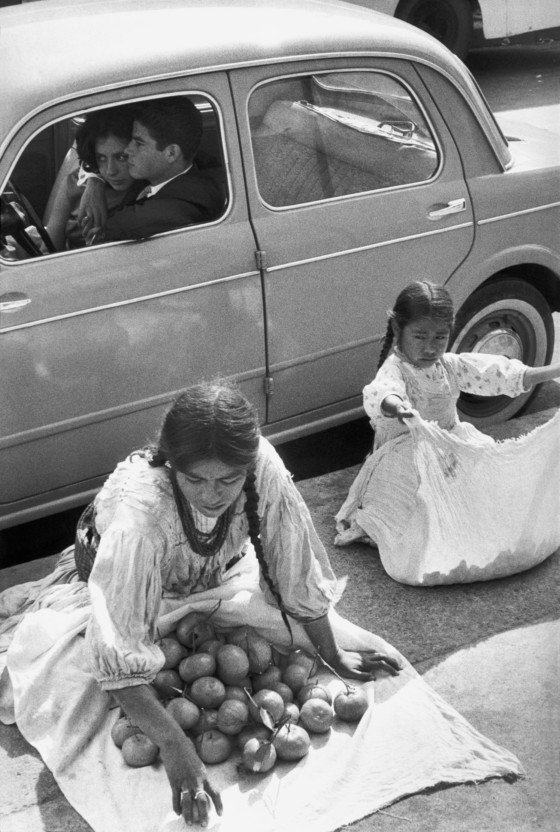

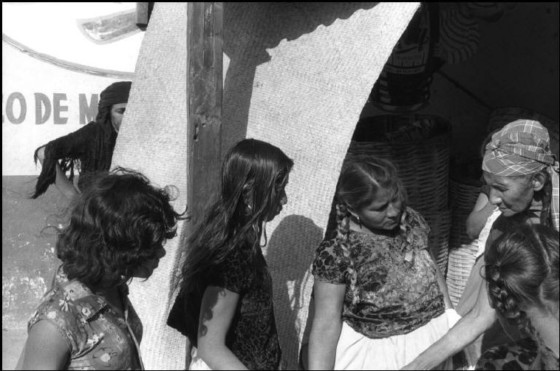

But Cartier-Bresson returned to the figures that had so fascinated him as a 26-year-old; his curiosity still drew him to roam the streets. It was a pilgrimage to his younger self, a personal testament to the place where, for Henri Cartier-Bresson, it all started. The resultant work, as well as his 1930s work, has become highly regarded by some of the world’s most influential cultural institutions. A photograph of a street musician with his violin sits in MoMA’s collection, and an image of two little girls dressed in white dresses selling apples by the side of the road is in the Victoria & Albert museum’s collection of Prints, Drawings and Paintings.