Shore Leave

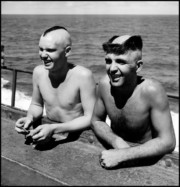

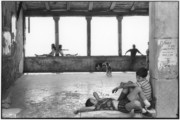

Wayne Miller travelled to Hawaii in the guise of an enlisted man to photograph the reality of US sailors at leisure — the images are now publicly available for the first time

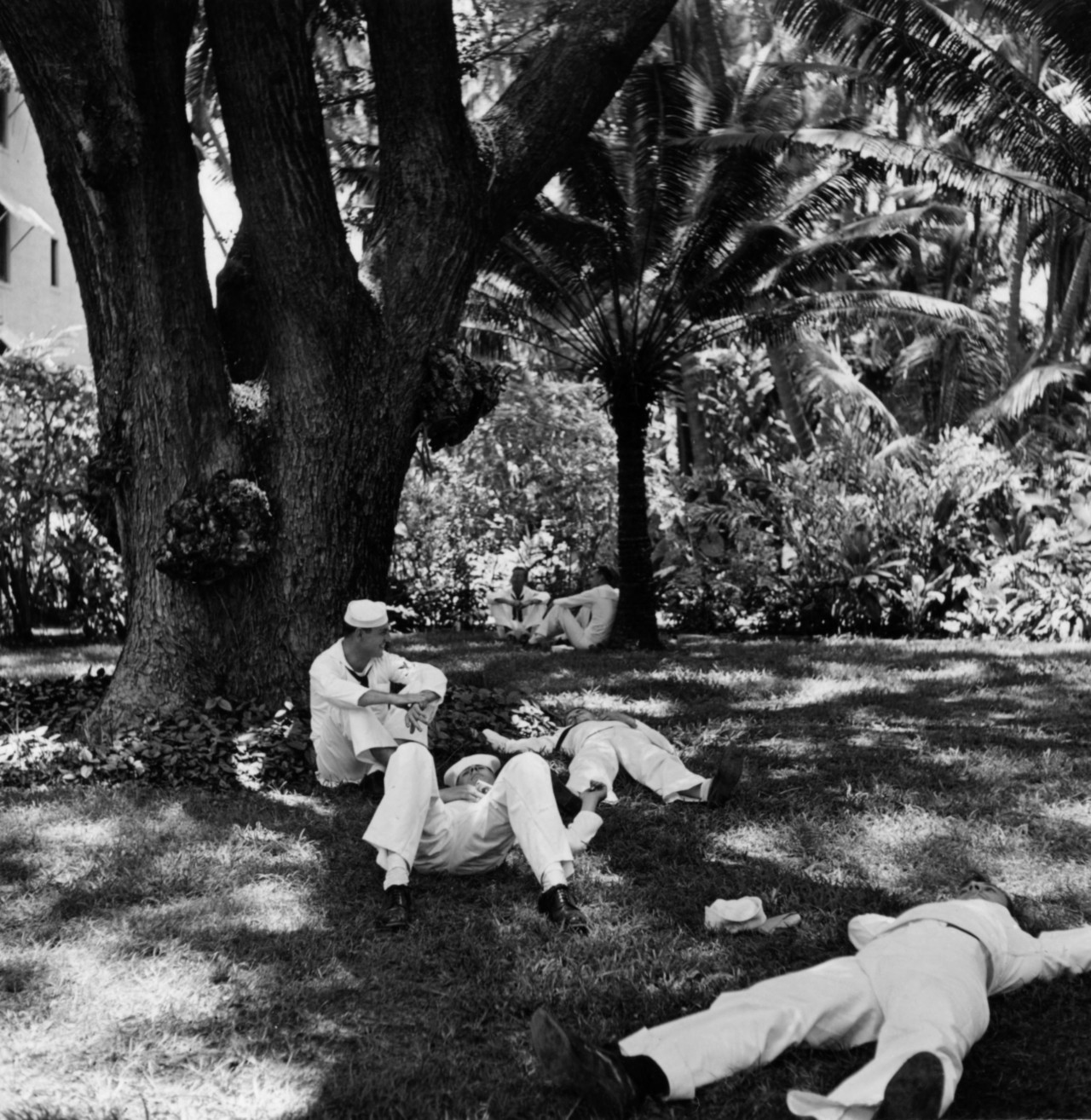

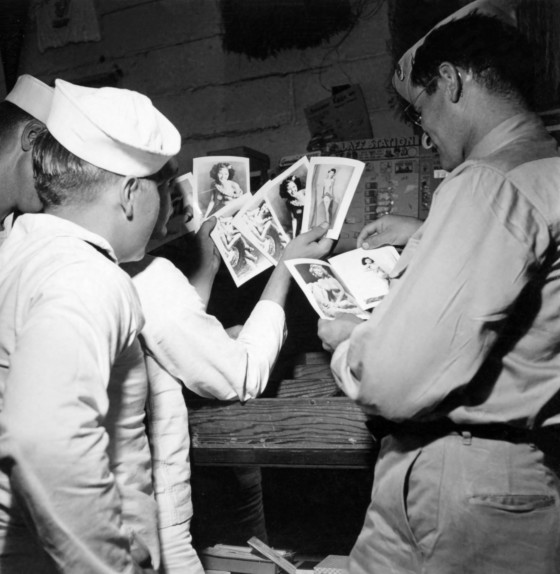

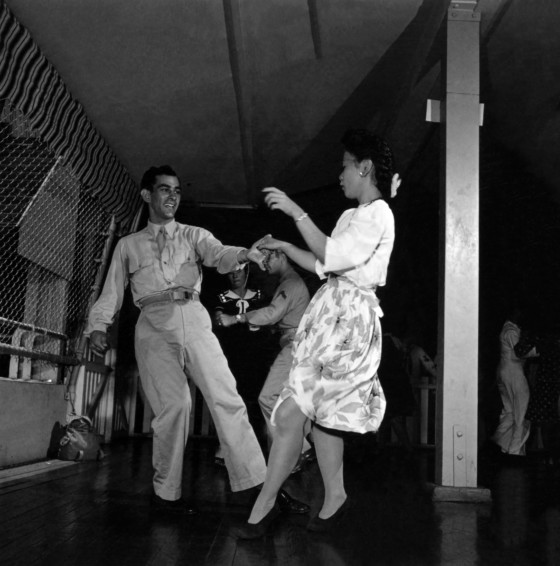

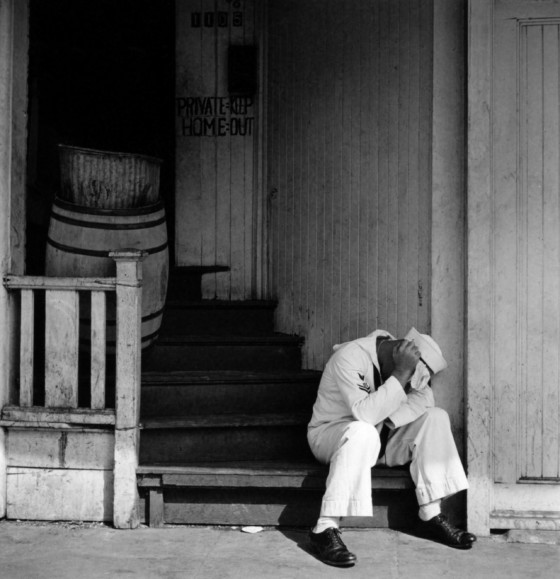

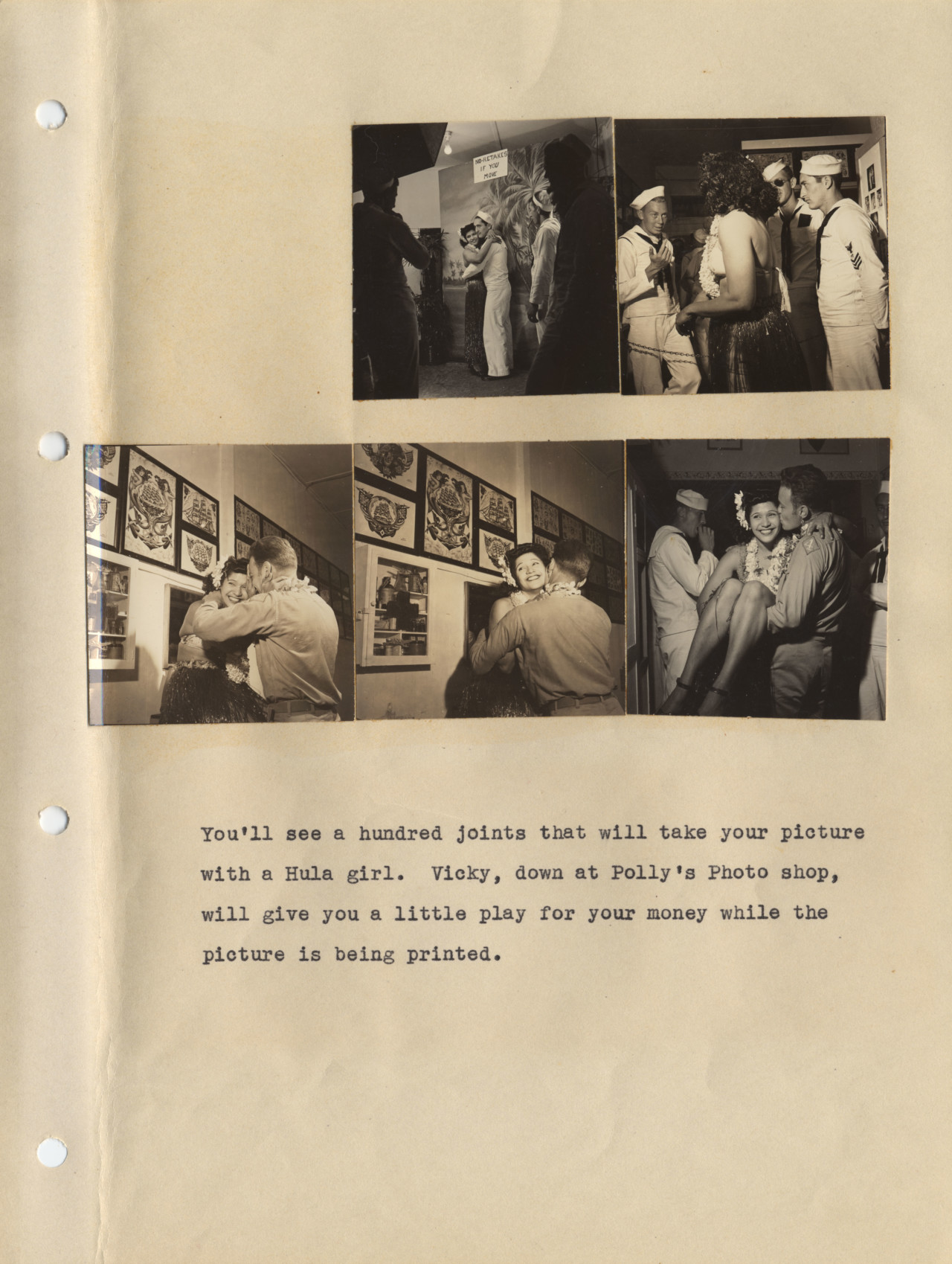

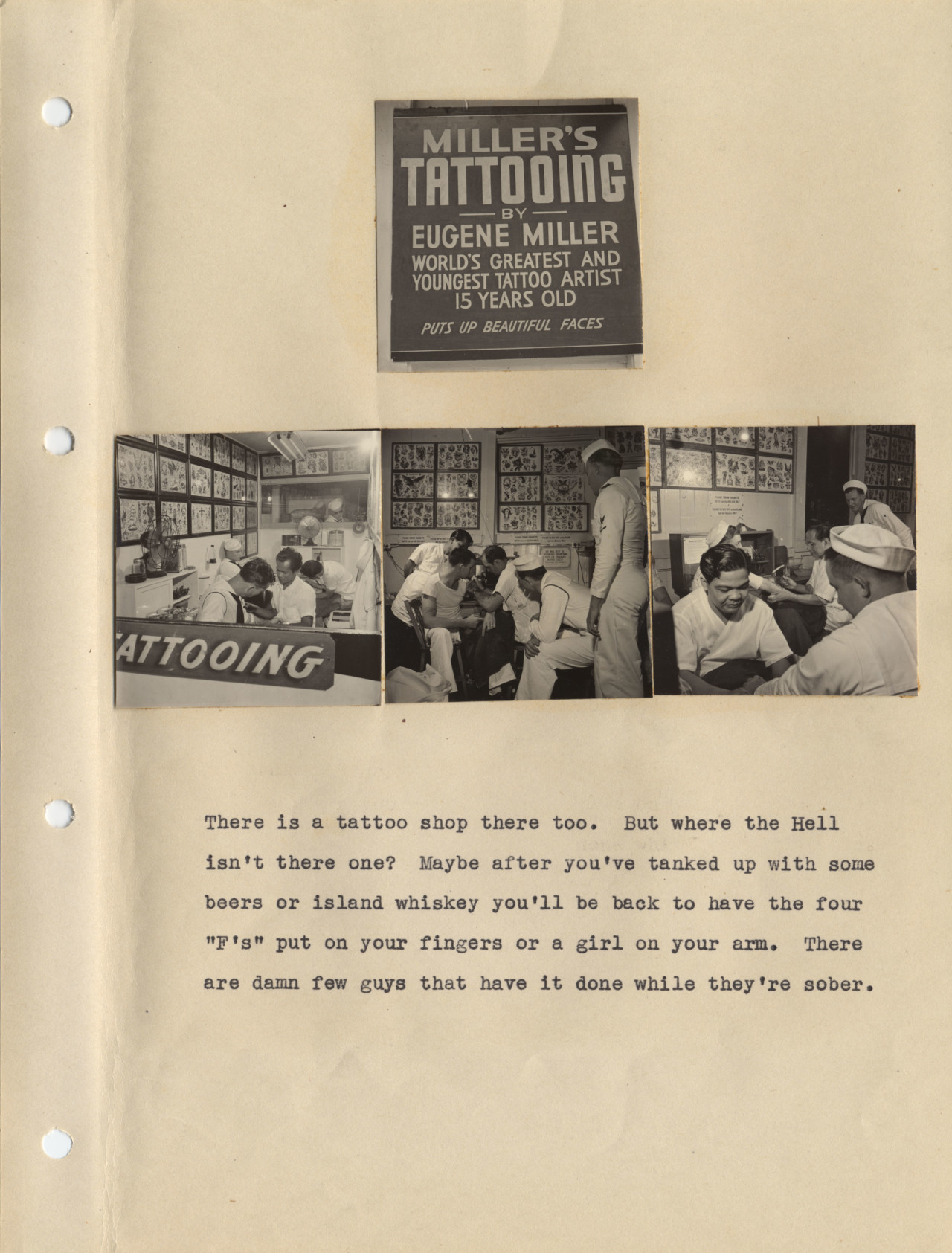

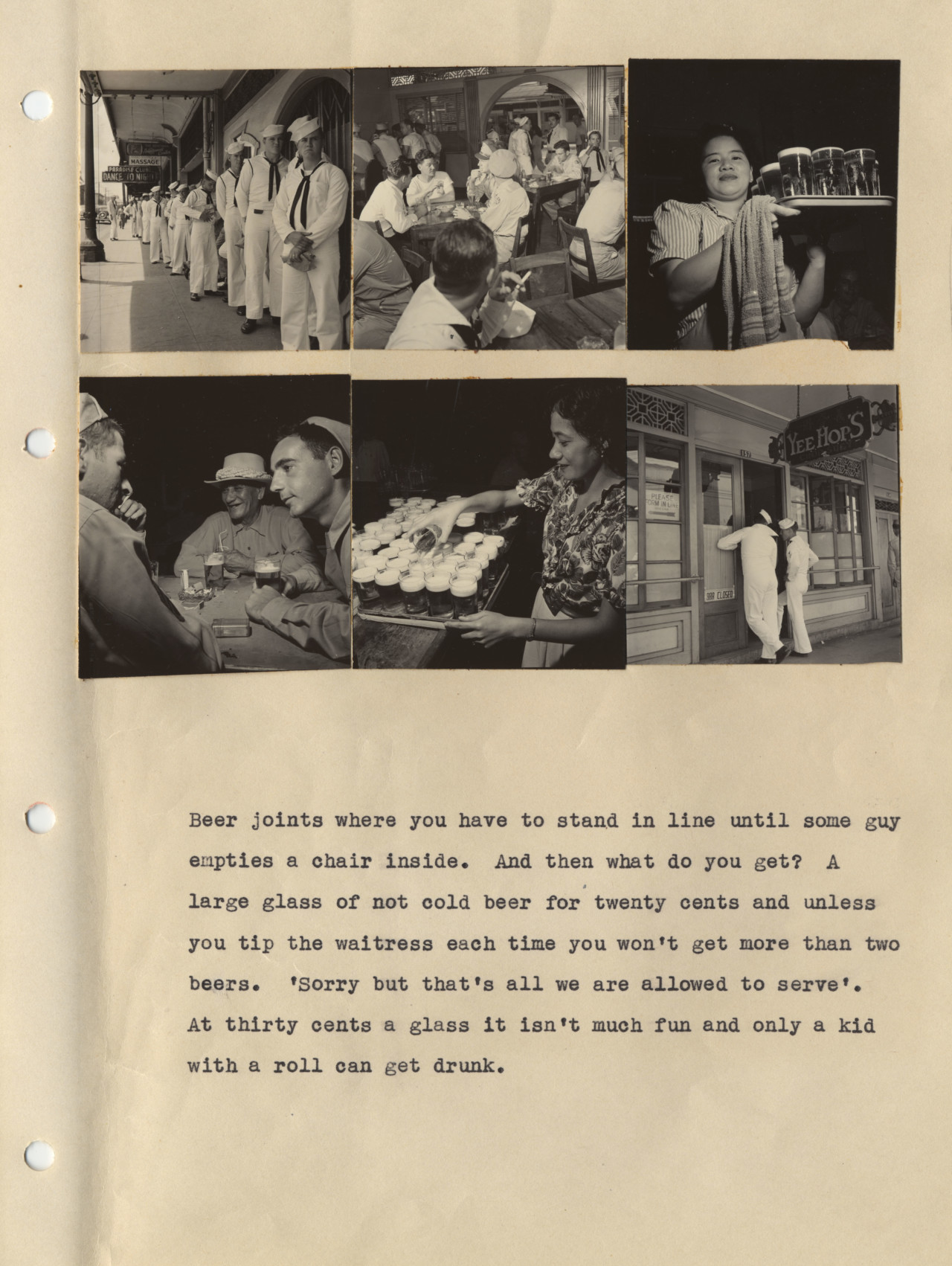

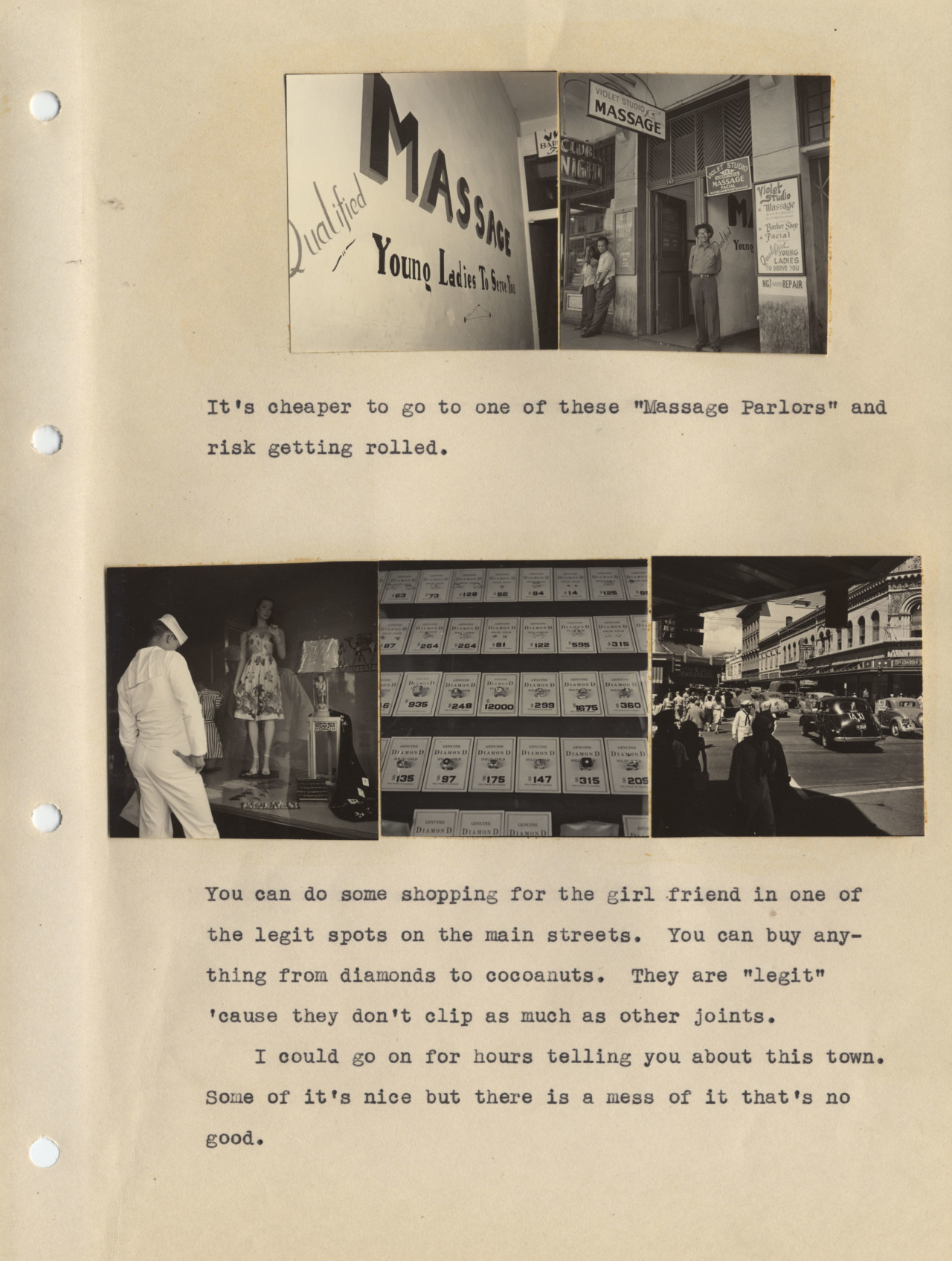

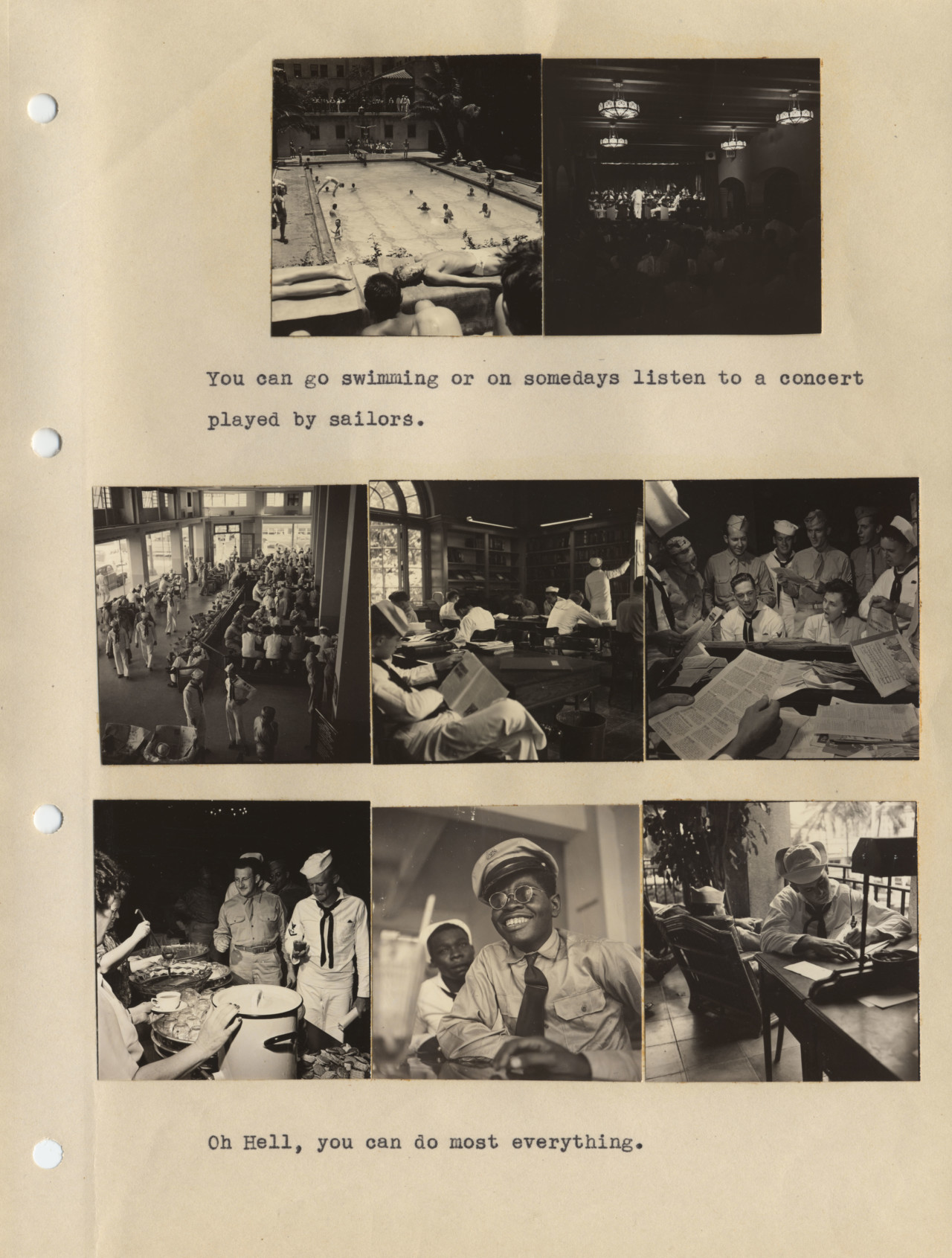

Shore Leave, Wayne Miller’s 1945 project made in Honolulu, Hawaii, revealed the vacationing activities of US Navy servicemen during their time off. Working undercover in the guise of an enlisted man, Miller captured his subjects engaging in a range of activities traditionally associated with holidaymaking sailors: sightseeing, gaming, tattooing, seeking female companionship, and of course, drinking.

The images were restricted by officials upon the project’s completion and accordingly have not been widely seen until now. Below, we share a selection of the photographs as well as selected pages from Miller’s original maquette he made for the project.

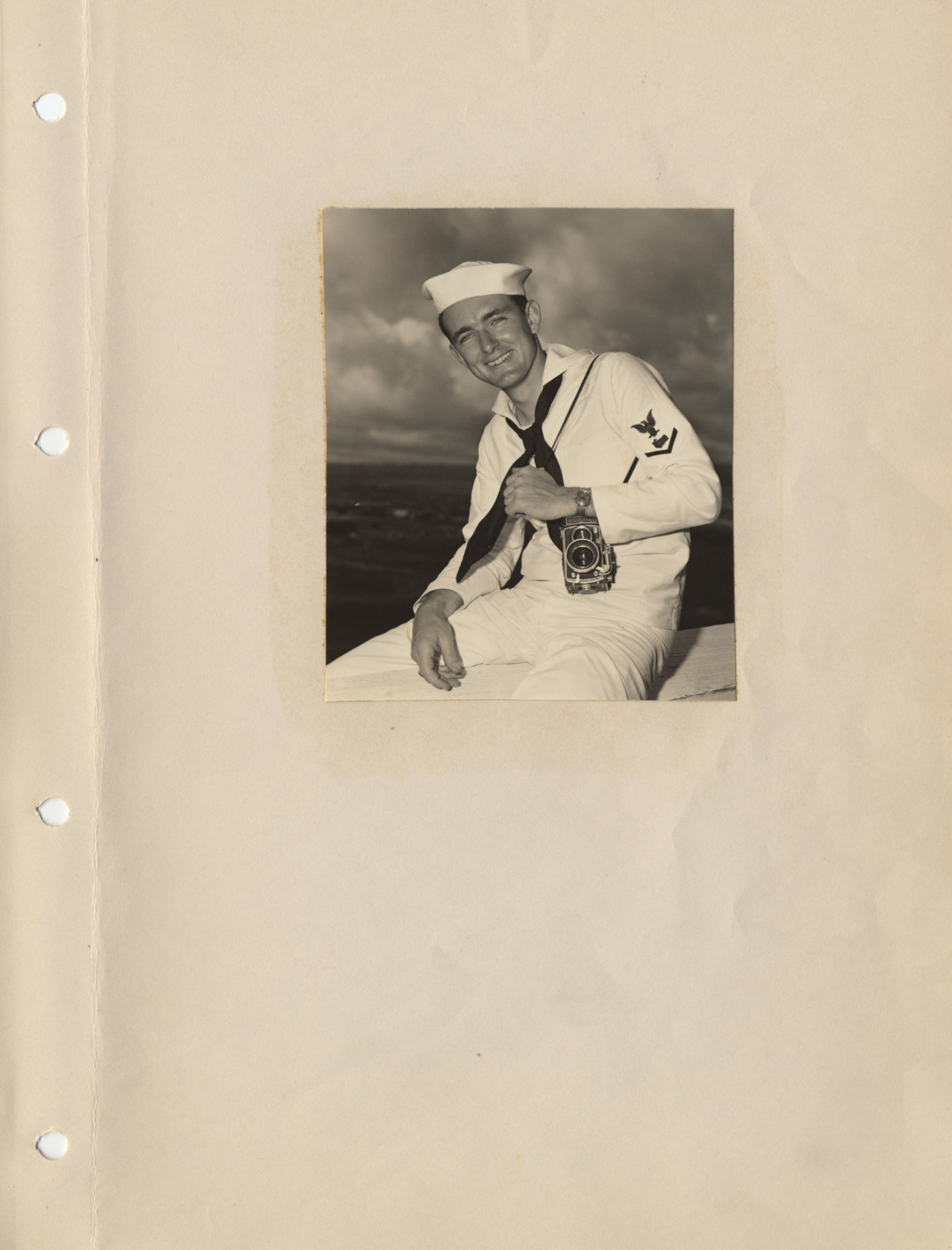

In 1942, as America mobilized for World War II, 24-year-old Wayne Miller, a newly-graduated student of photography with a background in banking, joined the US Navy. He was assigned to the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit, commanded by established photographer and painter Edward Steichen. Over the next three years Miller documented the Pacific War, from the lower decks of aircraft carriers to the skies above beach landings. He was one of the first photographers to visit Hiroshima after its destruction.

Though Miller’s unit was tasked with documenting Naval aviation for the purpose of recruiting new pilots, Steichen told him “I don’t care what you do, Wayne, but bring back something that will please the brass a little bit, an aircraft carrier or somebody with all the braid; spend the rest of your time photographing the man.” With this guidance, he was able to dedicate his attention to the common sailors.

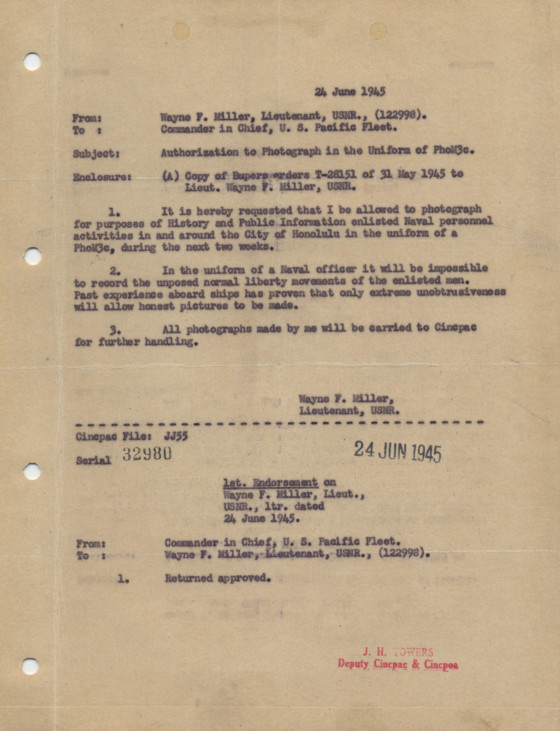

In June 1945, as the war in the east entered its closing months, Miller sent a proposal to his superiors: he asked that he be permitted to disguise himself as an enlisted man in order to pursue a project documenting naval personnel on leave. Miller knew that his subjects would not act naturally during their free time in port if they were approached by an officer with a camera (he and the rest of the photographers in his unit had officer ranks).

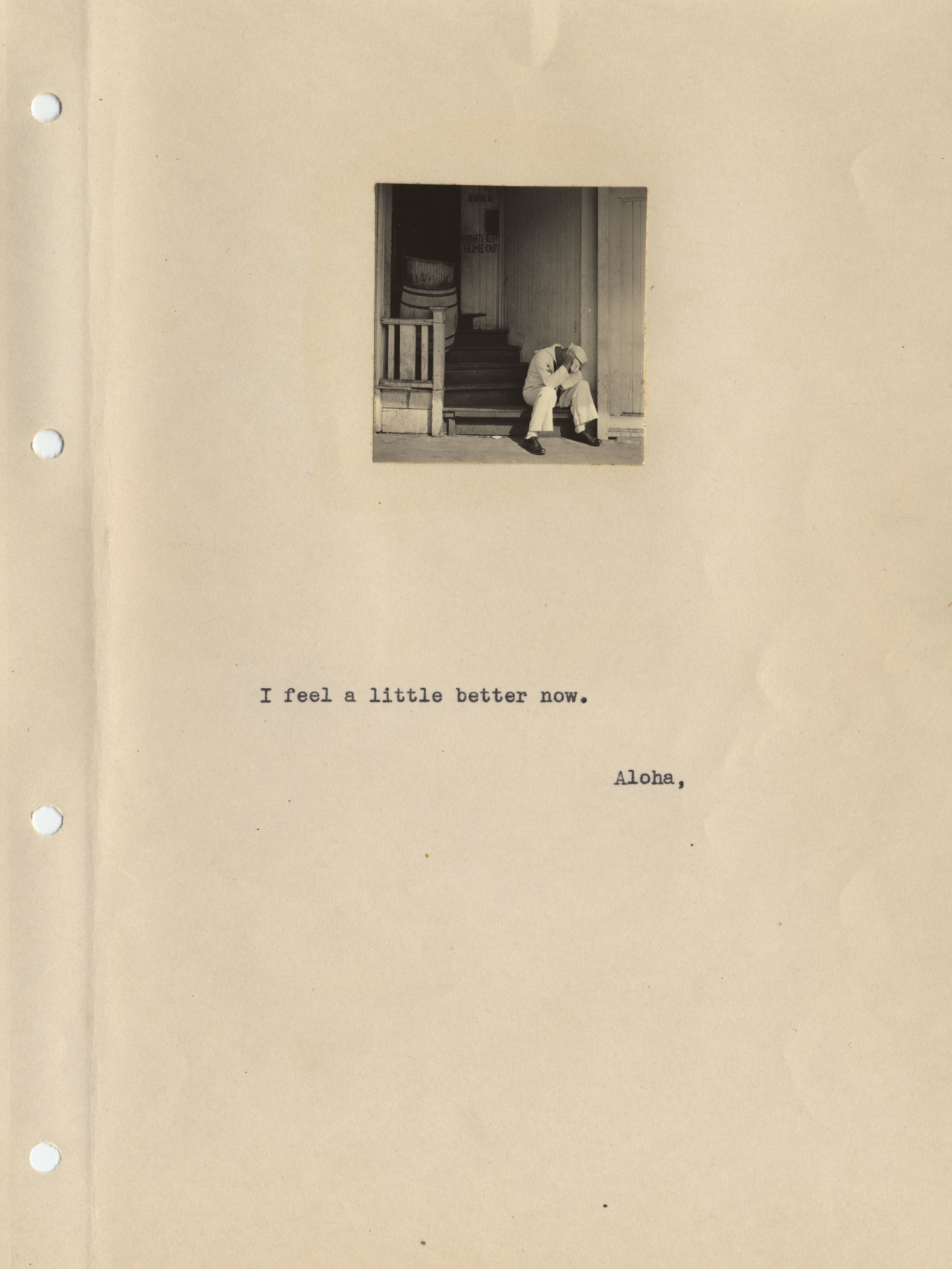

With approval granted and in disguise, Miller travelled to Honolulu. He documented the activities of the sailors, and compiled the resulting images into a maquette. Miller accompanied his images with a letter from the perspective of an ordinary serviceman, framing it as an irreverent guide to the Hawaiian destination for a prospective holidaymaking sailor.

“Dear Mac,

So you are all hepped up about coming to Honolulu? Sweet Leilani: Heavenly Flower: Romantic music of island guitars.”

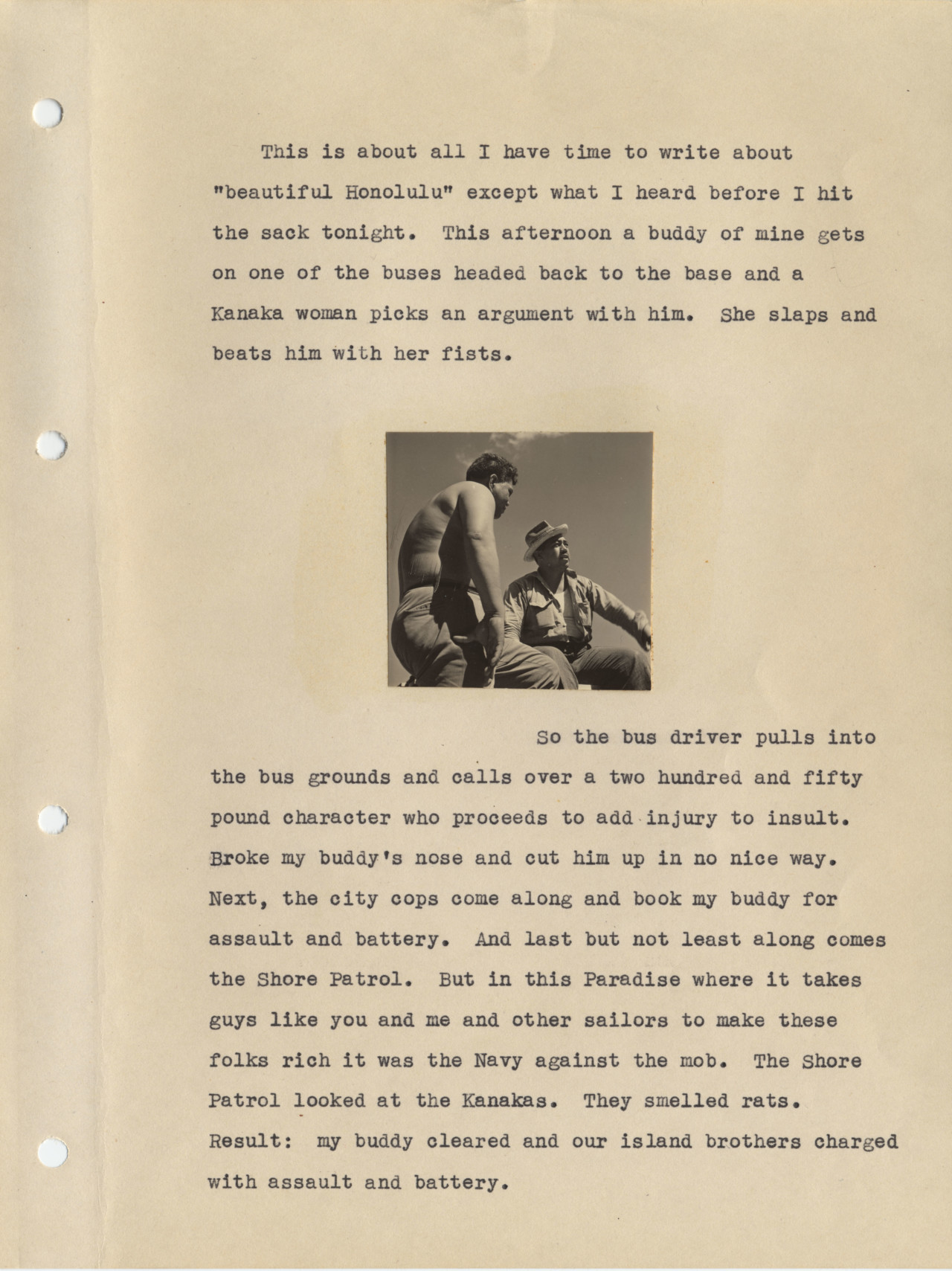

Miller pithily describes tensions between Hawaiians and American servicemen: accusations of swindling from locals, resultant disagreements and the physical altercations which follow.

“The monthly Navy Pacific payroll is 50 million bucks and a lot of it comes in here.”

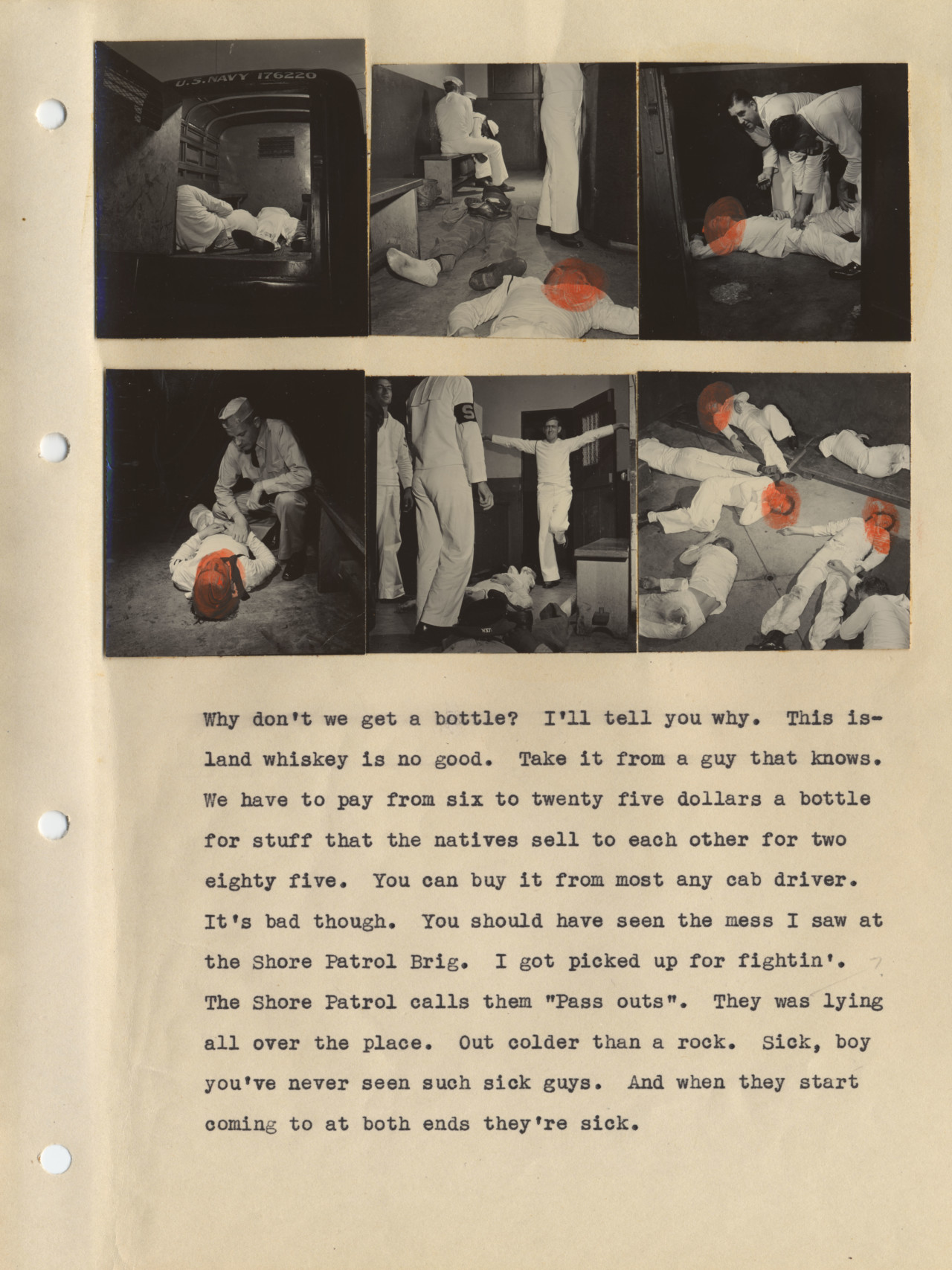

“This island whiskey is no good. Take it from a guy that knows. […] You should have seen the mess I saw at the Shore Patrol Brig. I got picked up for fightin’. The Shore Patrol calls them “Pass outs”. They was lying all over the place. Out colder than a rock.”

“A lot of fellows come in to town for it [church] but I don’t cause you’re probably sitting next to the guy that rolled you the night before. Can’t explain why but it makes me feel dirty all over.”

Miller also captures universal feelings of discontentment many may have felt whilst on holiday abroad — “They have some beer there too but if I were you I’d forget it. While you’re standing in line for two cans you’ll sweat out three.”

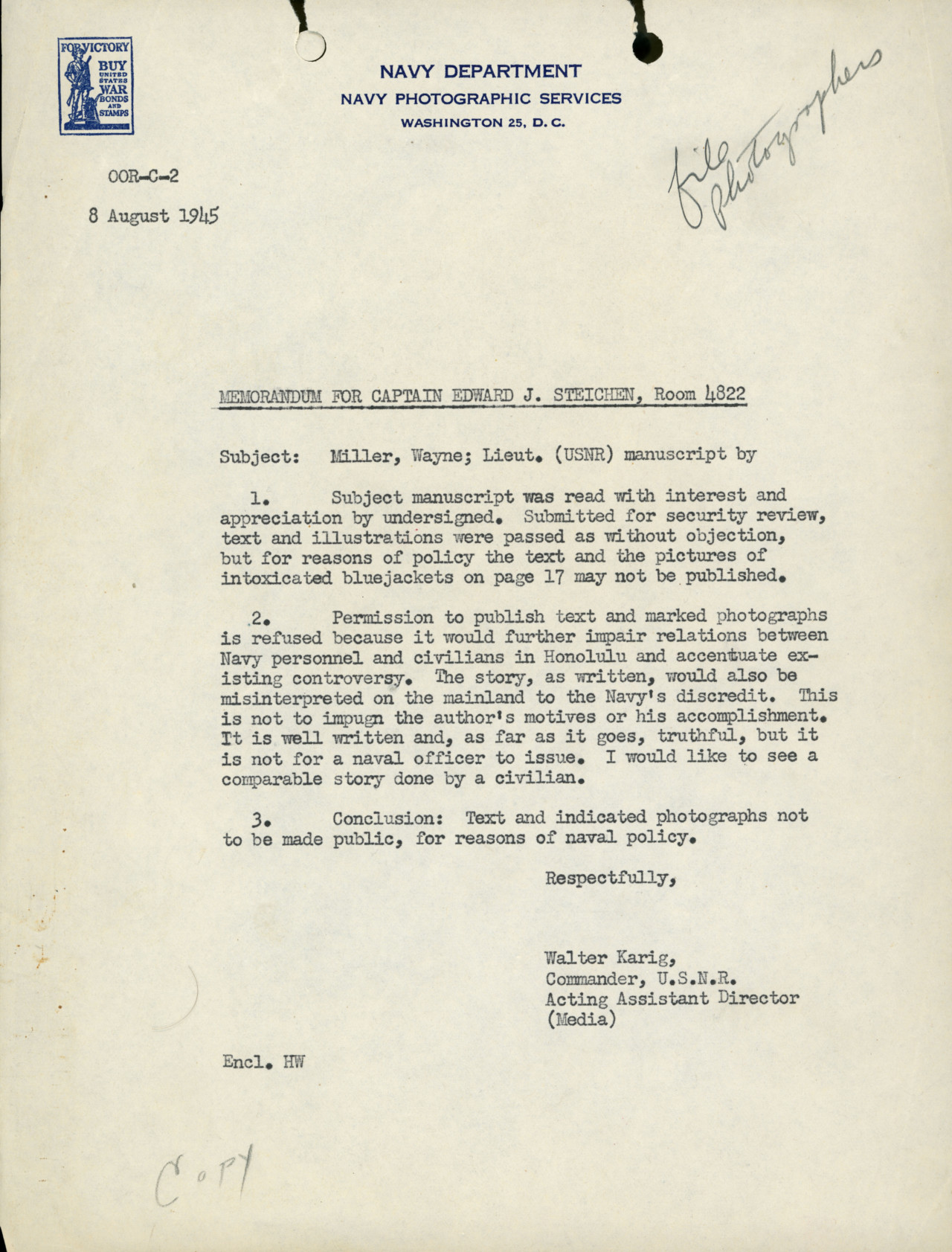

Upon seeing the finished project in August, the Navy deemed the images and accompanying text too susceptible to misinterpretion. While truthful, they could not be made public due to a concern that the project might “further impair relations between Navy personnel and civilians in Honolulu.” The images and the accompanying maquette were filed away until 2018, when Miller’s family found the work once again.

After the war Wayne Miller returned to his native Chicago. He won two consecutive Guggenheim Fellowships which enabled him to dedicate three years to a project about African-Americans living in the North, most notably in Chicago’s South Side. Miller taught photography at the Institute of Design in Chicago, then in 1949 moved to Orinda, California, and worked for LIFE until 1953. During the following two years he was Edward Steichen’s assistant on an historic exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where Steichen was director of photography. The landmark exhibition, titled The Family of Man, centered around the theme of Humanism in photography; it went on to become highly influential in the establishment of documentary photography as an art form.