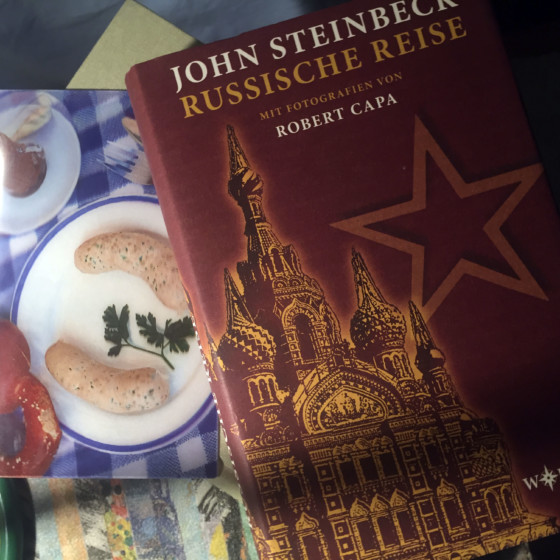

A Russian Journal Retold, Part 3: Travelling to Georgia

On the last leg of their journey retracing Capa and Steinbeck's footsteps, Dworzak and Strauss find themselves in Georgia including the Russian-occupied, de facto independent Abkhazia, plus an exclusive interview with the photographer

From Ukraine we travelled to Georgia. In 1947 Steinbeck had enthused about Georgians, their hospitality, their food and their irrepressible love of life.

He wrote in A Russian Journal that Russians “spoke of Georgians as supermen, as great drinkers, great dancers, great musicians, great workers and lovers…. Indeed, we began to believe that most Russians hope that if they live very good and virtuous lives, they will go not to heaven, but to Georgia, when they die.”

Perhaps as a consequence we were welcomed like royalty. Just like Steinbeck and Capa, we gorged on rich food and light white wines.

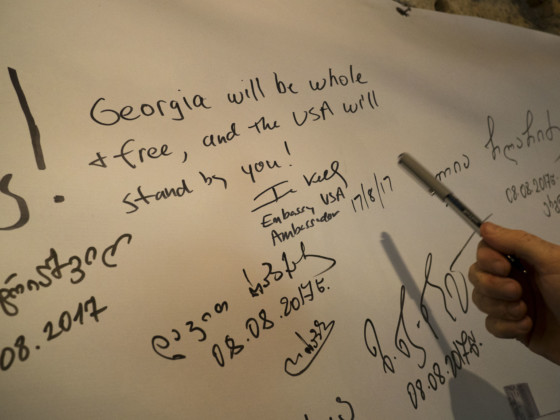

We were taken to the room where the local Writers’ Union had welcomed the American duo all those years ago. Shutters clicked, TV cameras were raised, and we were asked to explain our project and describe our impressions in detail.

We visited Stalin’s birthplace, and a forest fire.

Unlike Canada, my home country, where fire is fought by men in red jackets with hosepipes and heavy equipment and the public are kept well away, in Georgia it occasioned something of a social event.

The Prime Minister came to see it, as did the Patriarch of the Georgian Orthodox Church, and other notables. Songs were sung, prayers were intoned, and amid the swanky German limousines, officials gossiped about family and politics.

We went to a mineral water factory, to Batumi on the Black Sea Coast and then on to the unrecognised state of Abkhazia. To make the crossing from Georgia proper we had to take a horse and cart.

We found a statelet replete with its own army uniform, flag and endless cages of monkeys, some of whom were still traumatised from the fierce fight for the capital, Sukhumi, in 1992.

Pictures of the dead from that war, which still flares up occasionally in violent clashes, had been put up by the roadside on large posters in each village we drive through.

“This is a proper war going on between Russia and the West,” a former Georgian minister told me when I spoke with him two days later. “You in the west just haven’t fully understood that yet.”

An Interview with Thomas Dworzak

As the trip rounds to an end, Anne Bourgeois-Vignon speaks to Magnum photographer Thomas Dworzak to gather his impressions of the project.

What motivated your travels in Capa and Steinbeck’s footsteps?

I think it was the right moment to make this trip. 2017 marks Magnum’s 70th anniversary, as well as 70 years since Capa and Steinbeck made their own trip to the Soviet Union. In fact, I believe Capa’s trip to Russia was his first trip as a Magnum photographer (Magnum was founded in May and he left for Russia in July).

There is an obvious parallel between what Capa and Steinbeck set off to document, and what is going on in Russia right now, however you want to call it – “the new cold war”, the third way – and Russia’s relationship with the West. I wanted to capture a little slice of that.

What were you hoping to capture photographically?

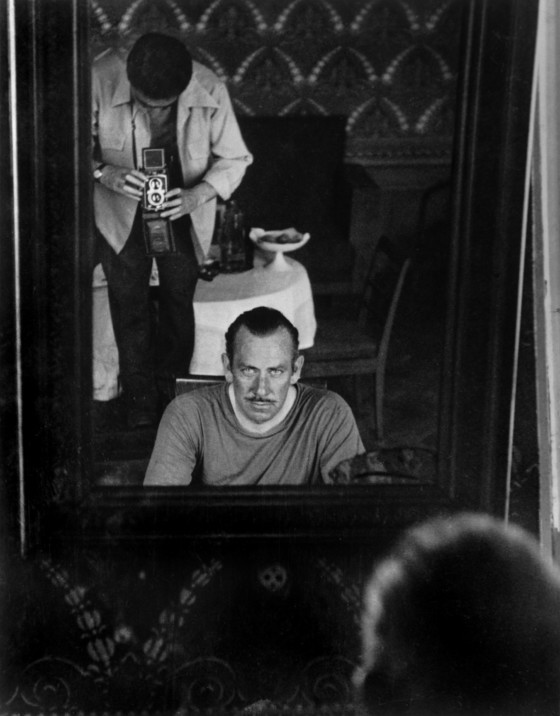

Creatively, my approach, along with Julius’, the writer who I travelled with, is normally quite different from what Capa and Steinbeck did for the Russian Journal. They only went for 6 weeks, whereas I have been documenting Russia for the best part of 25 years.

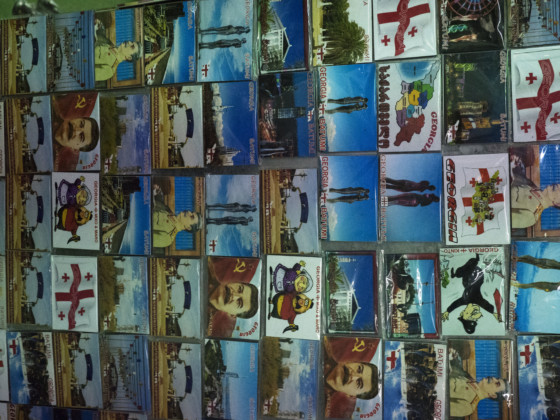

I had to find a way to recreate their freshness of outlook. My approach was to look at the surface of things, and to ask: what are the Russians, Ukrainians, Georgians trying to show us, what is their propaganda?

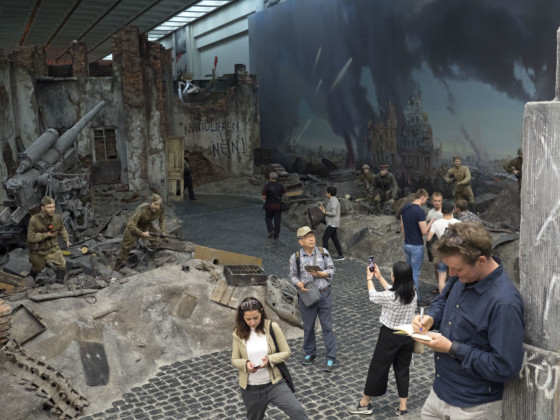

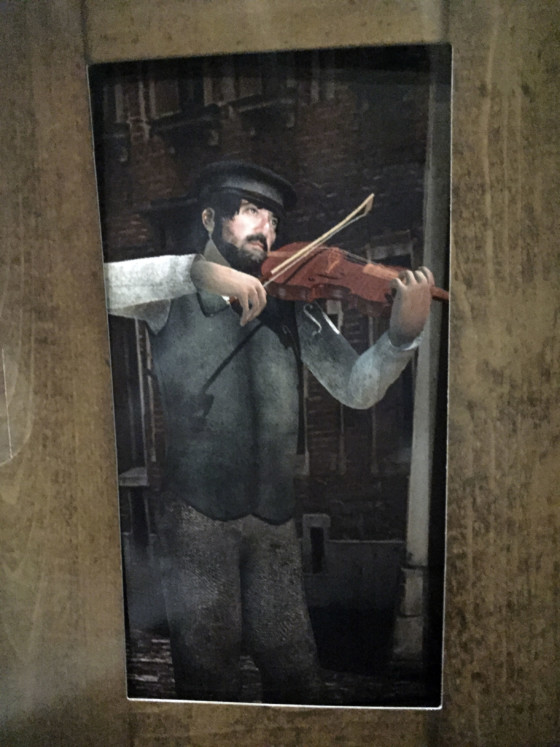

Capa and Steinbeck were extremely controlled in their movements in Russia and what they saw. A recent study showed how much the reality they saw was prepared in advance of their arrival. I was trying to recreate that situation by going on official tours, visiting and photographing museums, and the like. In my photographs, I wanted to play on the real and the fake.

How did your documentary approach as a photographer differ from Julius’ approach as a writer?

In fact, there was a bit of a creative conflict between me and Julius, who was looking for “the real thing”, journalistically – wanting to go up to the war front, for example. In such a short space of time, six weeks, I didn’t think it was possible to go far beneath the surface; I felt it was much more relevant to photograph what was being offered up for us to see, like a museum in Kiev where the government is already showing what the on-going war looks like – in the way it wants us to see it.

Our approaches were also complementary. For example, Julius interviewed someone who is considered one of Putin’s main, key, propagandists. It was right to speak to him, and of course he gave us propaganda. But it totally made sense to do this.

What was it like travelling and working with Julius for six weeks?

He’s great, probably much better than Steinbeck! No excessive drinking and only ate gluten-free food. It was all very 21st century. We’ve known each other over 15 years. Our work together was a playful trade off, and our differences became a bit of a game between us, like ping pong. What weird thing would I be looking to photograph, what serious, meaningful situation did he want to go to next?

What was the most important part of the trip for you?

Looking back, I think Russia was the most important part of the trip for me. I always have Russia in my neck; Russia and the former Soviet Union have been an essential part of my life for the past 25 years.

That said, I haven’t really shot a lot in Moscow in recent years. So, for me to come back and really engage in Moscow was something new, as usually I spend most of my time in the Caucasus.

I know the country pretty well – but that makes the challenge of photographing it even harder. It’s frustrating because I found it difficult to create enough distance, overcome my habits, to provide a new perspective.

Everything I have always done in Georgia has been trying to get into it as deeply as possible, and this time I don’t know if I really managed to do very much; but in Russia and Ukraine, I think I found the right space, I hit the right spot.