On the Trail of The Grapes of Wrath

Mark Power found that echoes of Steinbeck’s poignant novel abound in contemporary America

In 2015, Mark Power, as part of Magnum’s Postcards from America project, found himself travelling through the states of Oklahoma and the Inland Empire region of California. This, the third of Power’s Postcards trips, drew influence in both geographical and inspirational terms from John Steinbeck’s seminal novel, The Grapes of Wrath, which took it’s title from a line in the Civil War anthem Battle Hymn of the Republic, “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord / He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored”.

Steinbeck’s tale of desperation and resilience, set against the harrowing economic deprivations of 1930s dustbowl America, saw the fictional Joad family travelling westward in the hope of relief from poverty and new opportunities in California. The novel was controversial in some arenas at the time of its release, being publicly burned by some who saw it as a scurrilous attack on the American agricultural industry.

Power’s own trip followed this same broad route, punctuated by specific moments of cross-over as he passed through towns like Sallisaw – the home of the Joads, Paden, Daggett, and finally Barstow, CA, all mentioned explicitly in Steinbeck’s narrative.

However, more than allowing the book to direct his route minutely, Power took Grapes’ themes as inspiration, themes which are today – worryingly but perhaps unsurprisingly – as relevant as they were when Steinbeck released the book in 1939: economic hardship, migratory populations, predatory financial institutes and practices, and of course environmental change and agricultural upheaval.

Fifty years on from Steinbeck’s death, with The Grapes of Wrath enjoying an unhappy level of relevance, here Power discusses his work in Oklahoma and the Inland Empire, the influence of the novel upon his approach to photographing these States, and how and why his particular practice allows for a unique approach to documenting social issues.

The work made in Oklahoma and the Inland Empire of California which features in your ongoing Good Morning, America project was inspired, and geographically directed to an extent, by Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. You have spoken about being someone who works out what they want to do by doing it, on the move, more than premeditating at length. How longstanding was your interest in The Grapes of Wrath as a means of viewing America? Or was it something that became of interest to you after you started working in the American West?

Be careful about using the term, ‘American West’. My project is much broader than that. In fact, I harbor a secret ambition to make work in all 50 states. I’m somewhere around 30 at the moment. This is not an imperative, nor is it a driving force behind the project, but the nearer I get to it the more seductive it sounds.

As for Steinbeck, I remember reading Of Mice and Men some years ago; it was one of my daughter’s prescribed texts for her GCSE English course and I wanted to show some solidarity in sharing it with her. I loved it so much that I became a little Steinbeck-obsessed, and started to read a lot of his other books. I discovered he’d been in Russia with Robert Capa [see A Russian Journal], and I duly studied that, but it was The Grapes of Wrath which really touched me. I believe I’ve read it four times now, and listened to it as an audiobook while walking my dog. It was strange to be walking the English South Downs while listening to such an evocative description of the American plains.

Steinbeck, who was as much a journalist as he was a novelist, travelled with several families as they journeyed west from the American dustbowl to the promised land of California. The Joad’s, the family at the centre of the novel, are an amalgamation of those he met on along that road.

My trip to Oklahoma was, in theory, part of Postcards from America, although I broke away from the conventions of working in a team and instead travelled alone. Steinbeck had evoked in me – in my imagination – a landscape of such intensity (the opening paragraph describing the pathetic attempts of the last rains to nourish the parched gray and red earth is unforgettable) that I wanted to see it for myself. I thought it might be interesting to begin my journey in the eastern part of the state, in Sallisaw, from where the Joad family begin their journey.

I found myself trying to find the farm they’d left behind. Clearly, at this point, I was getting fact mixed up with fiction (or the other way around) and I had to keep reminding myself that the family didn’t actually exist. Nevertheless, there was something deeply moving about being in the very place the story begins.

Of the many visits to America that I’ve made since 2012 (my initial adventure with the Postcards team) this particular trip sits slightly ajar from the rest because of its close ties with the narrative of a novel. But it’s important to understand that I wasn’t trying to illustrate The Grapes of Wrath; instead, I simply followed the described route and stopped all the locations mentioned in the book as well as others in-between that many real migrant families (as well as the Joad’s) would have passed through. I tried to look at those places as if I were in the midst of the story, but within the context of the social and political landscape of America today. It gave my journey a structure, and forced me to visit specific places and not others, which rather differs from the meandering paths I normally take while working in America.

Sometimes fact and fiction came together. Okemah, for instance, which is mentioned in the book is also (as I learned when I arrived there) the birthplace of Woody Guthrie, the great American folk singer who wrote such poignant songs about dustbowl America. It’s wonderful when two pieces of the same jigsaw unexpectedly come together. I can imagine one feeding off the other.

The Grapes of Wrath deals with issues which have come full circle since it was written in the 1930s: the neglect and mistreatment of rural and migratory workers, the alienation of the working classes, and of course the impact of climactic shifts and extreme weather – be it the American dustbowl of the 30s or the California wildfires of recent weeks. Did the permanence, or perhaps alarming recurrence, of these issues form a big part of your motivation to make this work?

Most definitely. Throughout my ongoing work in America I’ve noticed a theme of transience emerging. I have many pictures of people apparently moving from one place to another, as if something better awaits around the next corner. This is at the core of photography too, and it’s something I’m constantly at war with. Instead of succumbing to the urge to move on because the next place must surely be more interesting, instead I try to stick it out and wait, because there’s always something where I already am. It just takes patience to find it.

Oklahoma, it seems, is now a leading centre of new technology. Oklahoma City is booming and its population increasing. Meanwhile, climate change and increasingly ferocious forest fires in California, along with a movement of people eastwards into the desert, where land is cheap but life is hard, encourages and suggests, a movement of people in the opposite direction. Of course, it would be too simplistic to suggest that there are thousands of people making their way back from California to Oklahoma, the opposite of the journey described in Steinbeck’s novel, but there is a kind of ironic metaphor at work here. That’s part of what I was tapping into.

Your approach is famously particular, and to those unfamiliar with it, the idea of it being a fitting practice for photographing ‘issues’ may seem surprising… When it comes to documenting society, or social issues, what are the benefits your specific approach offers?

Generally speaking, my pictures rely on an accumulation of details. Showing them online, rather than as a print or in a book, can be frustrating because these details often disappear. It’s my way of making work about several issues at the same time, all interlocked with each other. I’m rarely addressing just one theme; life is far more complex than that. I’ve spoken in the past about making what I might call ‘democratic pictures’, by which I mean that a viewer can bring their own interests or prejudices to an image, and take from it whatever they wish, simply because everything is in focus. It does not insist that a viewer should look at one thing and not another, which selective focusing would do.

Do you think the sense of distance in your work, which you have described previously, makes literature an especially alluring source of inspiration for you? That contemplative slowness, and care in your work?

Yes, I think that’s correct. When I read a novel I’ll often go over passages again and again to savour the beauty and complexity of the language. If I find a writer I like the plot tends to recede into the background and I find myself obsessing over the writing style. Cormac McCarthy, for instance, who I’m usually reading while travelling through America, is a good example. I’ve not thought about this before in relation to my own picture making, but yes, I suppose I’m trying to make my own well-constructed ‘visual sentences’ that say something poignant, without using any more ‘words’ than I need to, and in the most evocative and beautiful way that I can.

The series included a number of what might be called ‘traditional’ portraits. Your more recent work often contains people as part of a land or city-scape, indeed sometimes only a very small part. Your earlier work – like Sound of Two Songs – featured more close-up portraits. What do the more tightly focused portrait images in this series lend to the wider body of work and what made these people stand out to you in terms of the project?

As my work in America has progressed I’m making fewer and fewer portraits. I don’t know why this is, except that I find it extremely difficult to flip between a wider landscape and specific details. I tend to get into a ‘zone’ and stay there.

I’m not sure what to do with the portraits I’ve already made. There are none in Volume One of Good Morning, America and it’s doubtful there’ll be any in Volume Two either. There’s a possibility they’ll all be gathered together in the final book along with a number of texts I’m about to start commissioning in order to contextualize the entire body of work. We’ll see. But right now I’m content to photograph people in the distance, to use them as symbols of human presence rather than anyone specific. Or they add a sense of scale. While I do of course speak to numerous people throughout the course of a day, mostly because I’m constantly being asked what I’m doing, I find that negotiating a portrait tends to break the concentration I need to retain in order to somehow ‘separate’ myself from the landscape around me, to be observational, and to retain my stance as an outsider, as someone from somewhere else.

Some might see your ongoing work in the States as dwelling upon the grim realities of middle America, and indeed the challenging realities facing many Americans. Your work in Flint, MI, for example homed in on a place that has gained almost emblematic status for the problems America faces. The Grapes of Wrath is, perhaps, a positive book about a very negative situation – at least in as much as the resilience of the Joads, and their survival is a core part of the novel. Do you see your work in America as having an overriding tone or message in a comparable way?

Your use of the word ‘realities’ suggests that you agree there is something wrong, something broken at the very core of America. I believe most people feel the same. And while I don’t go out of my way to search for this it does seem to crop up again and again. I wanted to go to Flint because of Michael Moore’s associations with it… through his films I felt a connection with the town and I wasn’t disappointed. Likewise, I started a recent trip in Fargo, North Dakota because I love the movie of the same name so much, and ended it in Rapid City, South Dakota (close to Mount Rushmore) where much of North by Northwest is set, again a touchstone for me.

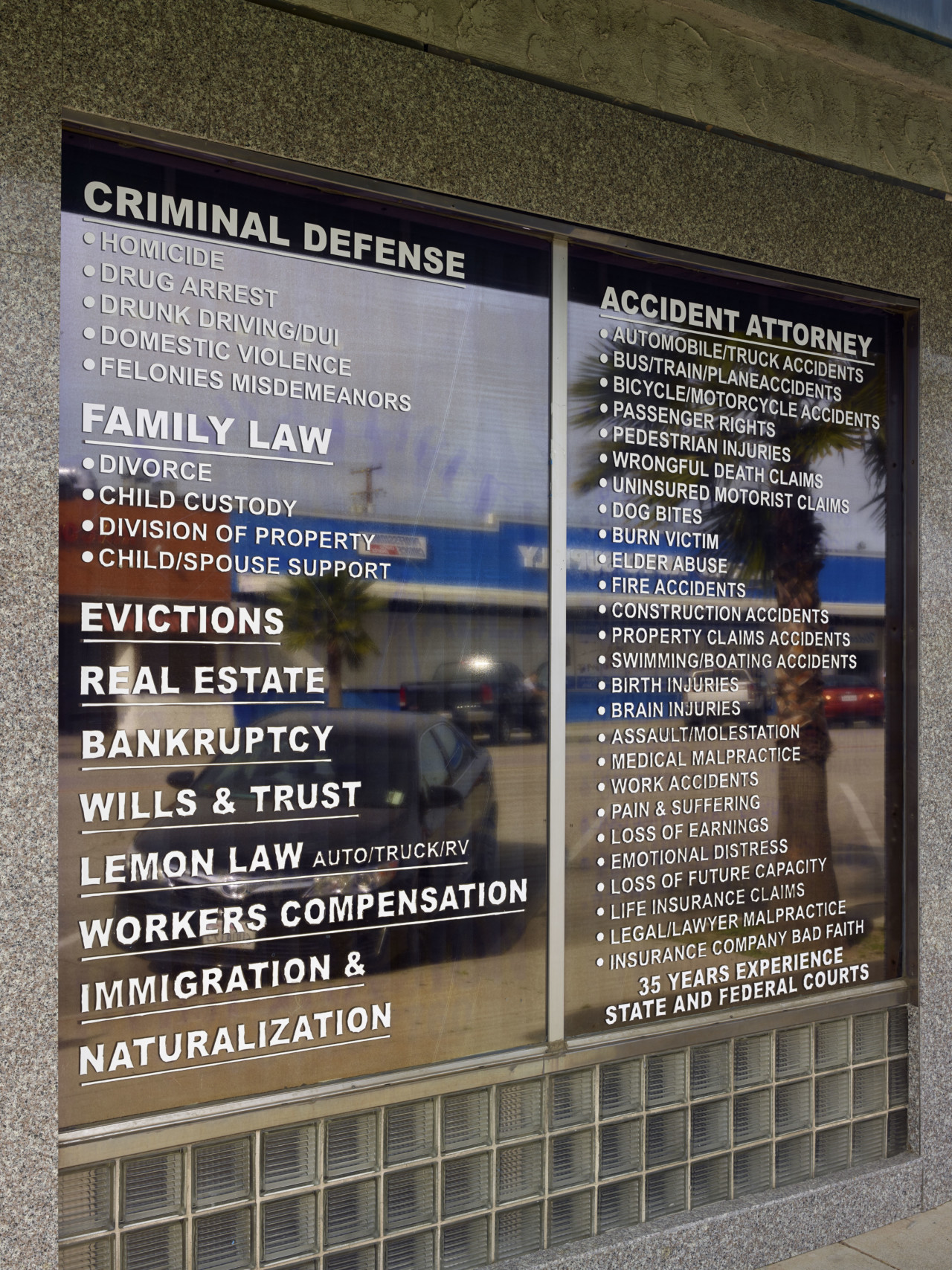

Another – if not perhaps the main – enemy of the Joads in the book is the financial system, and its taking advantage of the vulnerable. Images in the project, most specifically the vinyl window stickers advertising legal aid for those facing eviction or bankruptcy seem to nod to that aspect of the book. How much do you see that particular theme of Steinbeck’s novel being played out again today during your ongoing work in America?

Indeed, Steinbeck’s novel remains remarkably poignant. The picture you refer to (Attorney’s office. Fontana. California. USA. January 2015) is a response to one of the themes of the book, which I was reading (yet again) while I was there, but in an updated context. Also in California I made another picture (San Bernadino. California. USA. January 2015) of a sign advertising an organization called fastevict.com … bad typography stating the name of the company followed by a phone number. It’s already chilling enough, but, to make matters worse, it sits protected behind a brutal metal fence covered in barbed wire. Again, it was a response to the book. But, as we know, not only does good literature enable us to see the world differently… it also helps us notice things we might otherwise have missed.

This project has become so large that this specific trip forms only the first of a five-part book series. How does this particular chapter fit into the wider project, and how do you see the rest of the America work unfurling?

There’s something you shouldn’t misunderstand about the process at work here: with each subsequent book we’ll always be able to go right back to the beginning of the project, in 2012. The publication of Volume One does not mean that everything I’ve done up to this point is now done and dusted, finished with. It’s very likely that pictures from my Oklahoma and California trip of 2015 will crop up throughout the entire series, but removed from the context of my original idea. We may even use the same picture twice, but in different sequences. Let’s see.

I’ve committed to continue my project until 2022 (fingers crossed) so that it covers a decade. That’s an arbitrary period of time, certainly, but it appeals to my sense of neatness and logic. As I near the end the question of what I might do next occasionally crosses my mind. This is certainly my (excuse the pun) Magnum Opus, the biggest and most ambitious project I have ever done, and probably will ever do. I suspect I may feel bereft at the end of it all.