Searching for the Light

His life was marked by almost constant war. And it was war that took him, just nine years after he co-founded Magnum Photos. Peter Hamilton previews Carole Naggar's exhaustive new biography of David 'Chim' Seymour.

Carole Naggar’s remarkable new biography of perhaps the most enigmatic figure among Magnum’s founding fathers – born Dawid Szymin, but known through much of his short but extraordinary life more simply as ‘Chim’ – leaves you thinking, “I would have loved to have met that man.”

Speaking to the photo historian and author ahead of the launch of Searching for the Light. 1911-1956, published today by De Gruyter, we agreed on the ways in which Chim’s life stands as a symbol of the guiding ethic of the committed photographer, and what Magnum, as a collective, stands for.

Photographers may often be called upon – or more properly feel the need – to be shapeshifters, trading their own personal individuality for the anonymity of the person behind the camera, rather than the subject of its lens. And this is especially the case where their subject matter is predominantly situations of human conflict and their consequences for those caught up in the maelstrom, and which marked almost the entire lifetime of Chim.

Born in Poland in 1911, he also grew up to know a lot about antisemitism and its rapid growth in the period of his youth. His Jewish family owned a prominent publishing house in Warsaw that produced books in Yiddish and Hebrew, so although his background was one of middle-class ease, it was set against a backdrop of mounting antisemitism in the 1920s and ‘30s – although such insecurity had been evident even earlier.

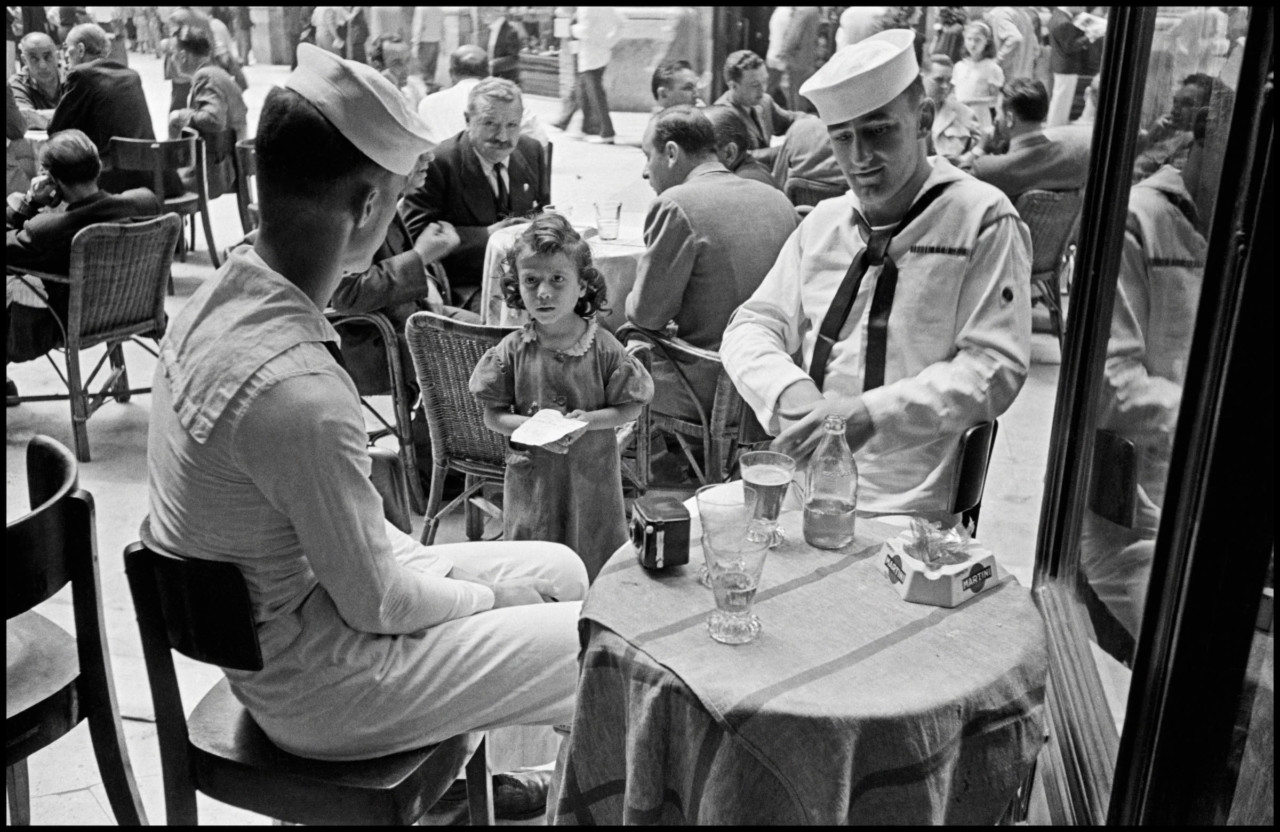

This perhaps explains why his life was also marked by so many linguistic journeys, from the Yiddish, Polish and Hebrew of his family, to his acquisition of Russian, German, French and English – although the latter was only acquired when he ended up in New York in 1939, and it prefigured his final acquisition of Italian in the 1950s when he was working on his great documentation of children’s illiteracy after the war in Southern Italy for the newly created UNESCO.

Naggar’s profound and exhaustive research into Chim’s life covers every possible base, and also touches on contemporary issues, with so many parallels that can be drawn out between the current conflict in Ukraine as an echo of the 1930s.

Naggar (whose previous books include Magnum Photobook: The Catalogue Raisonne, Saul Leiter: In My Room, and Bruno Barbey: Passages), tells me about her access to the Magnum archives and to Chim’s contact sheets tracing his photographic travels from 1934 to 1956, and to the surviving fragments of his correspondence. I tell her that it feels like being immersed in Chim’s world whilst reading the book, so clear and vivid is its account of what was, by any measure, a most remarkable life – though one ended by a cruel and pointless death in a stupid and random accident of war.

She believes that Chim’s family background in publishing may well have been decisive in his career as a photojournalist. “If you are born into that world, you have a very much more sophisticated perspective on how photographs can be used,” she says. “One thing I discovered was that whilst still a student he was an intern for a Leipzig newspaper, and that is where he got his first view of the press.”

He possibly knew Gerda Taro at that time, as both were students in the city and probably had friends in common, with a similar political outlook, and both were Jewish. A fascinating insight into their later relationship came about when the famous ‘Mexican Suitcase’ was discovered, containing long-lost negatives from the 1930s by Chim, Taro and her companion, Robert Capa.

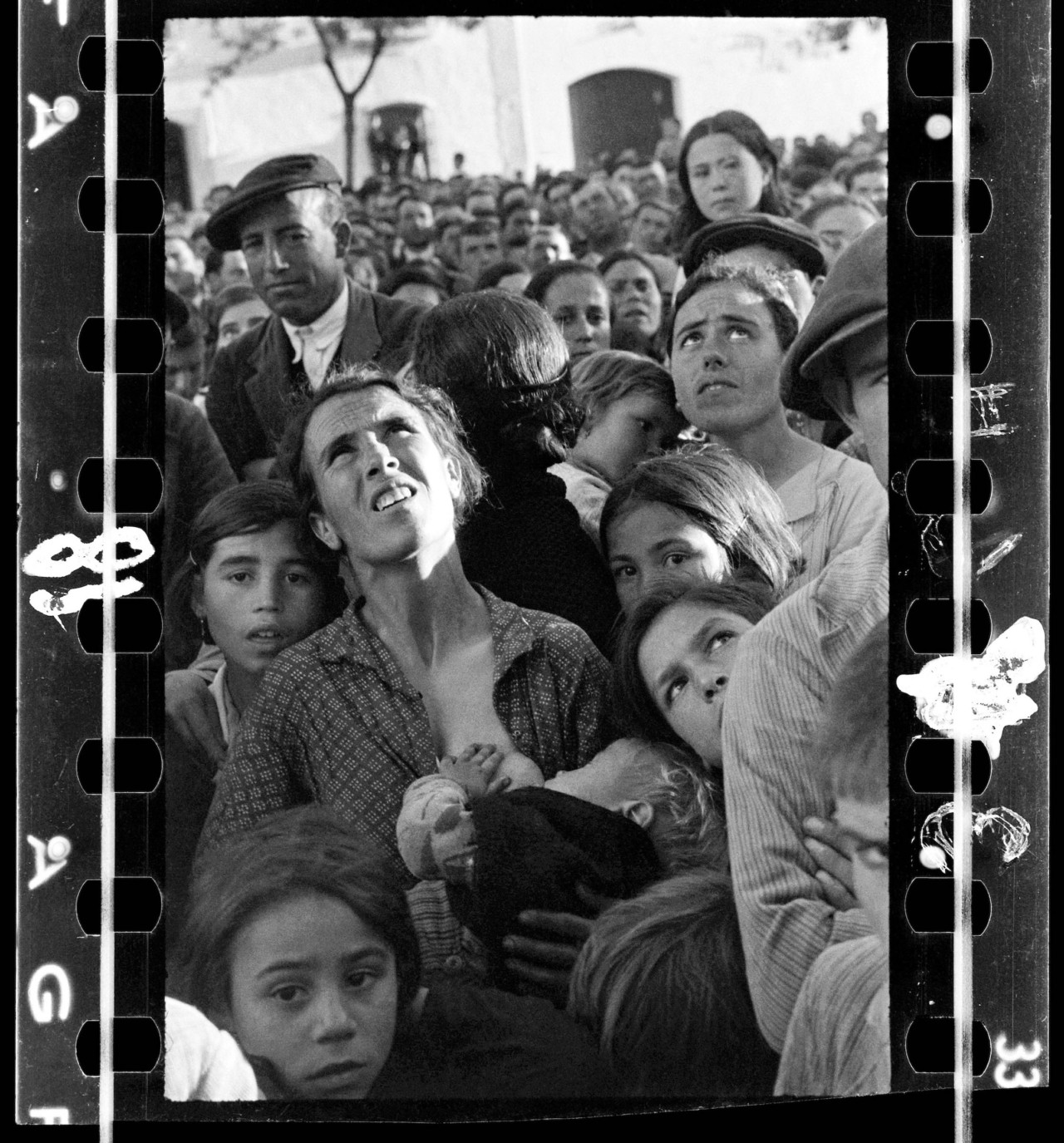

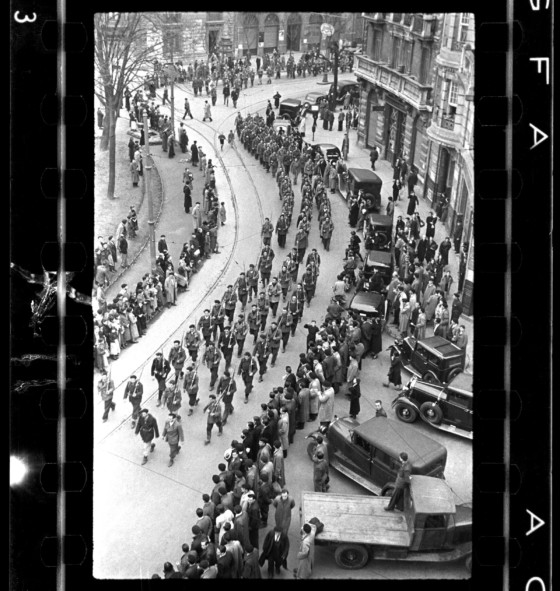

Naggar sees Chim’s profile being raised by her biography, particularly among young photographers, in part because “his work emphasizes the fact that photographers can see things that only photographers can.” As in the 1930s, the power of the single image, especially against the backdrop of press reports, can be very powerful in placing the focus on the savagery of dictatorial power, as displayed in Spain in the 1930s and contemporaneously in Ukraine. Where Chim’s world had the newsreels, we have 24/7 television coverage, but it remains a striking fact that a single image is potentially much stronger than a plethora of video clips.

Chim was, of course, working in a different world, and as Naggar points out, he came to his maturity as a photojournalist in the 1930s, when the French magazine Regards hired him as a full-time contributor. Its philosophy was that “while photography may be truthful, it is not neutral.” Chim adopted the convictions of his colleagues that they wanted to use photography to redress social inequality, and ultimately to “change the world whilst recording it.”

Indeed this credo came to underpin the rest of his working life as a photojournalist, which lasted until his final assignment to the Suez conflict of 1956.

Naggar’s exhaustive research highlights all of the encounters and experiences that were the way stations of his life and career; the points of connection to other photographers and the many different assignments that his profession introduced him.

Willy Ronis first met him in the mid-1930s, shortly after Chim came to Paris from Poland. They became friends, and for a while, Chim was able to use Ronis’ father’s photographic studio darkroom in the Belleville district. They sometimes covered the same event, and on one occasion the two photographers made almost identical photographs of a communist demonstration by the Mars group, a four-man choir at the Mur des Fedérés in the Père Lachaise cemetery (1937). Chim’s photo made it into Life magazine, but for a while Ronis suspected it was his version of the same event (wrongly, as it turned out).

He also met Capa and Cartier-Bresson whilst in Paris, with whom he would later be a co-founder of Magnum, along with George Rodger.

"His work emphasizes the fact that photographers can see things that only photographers can."

-

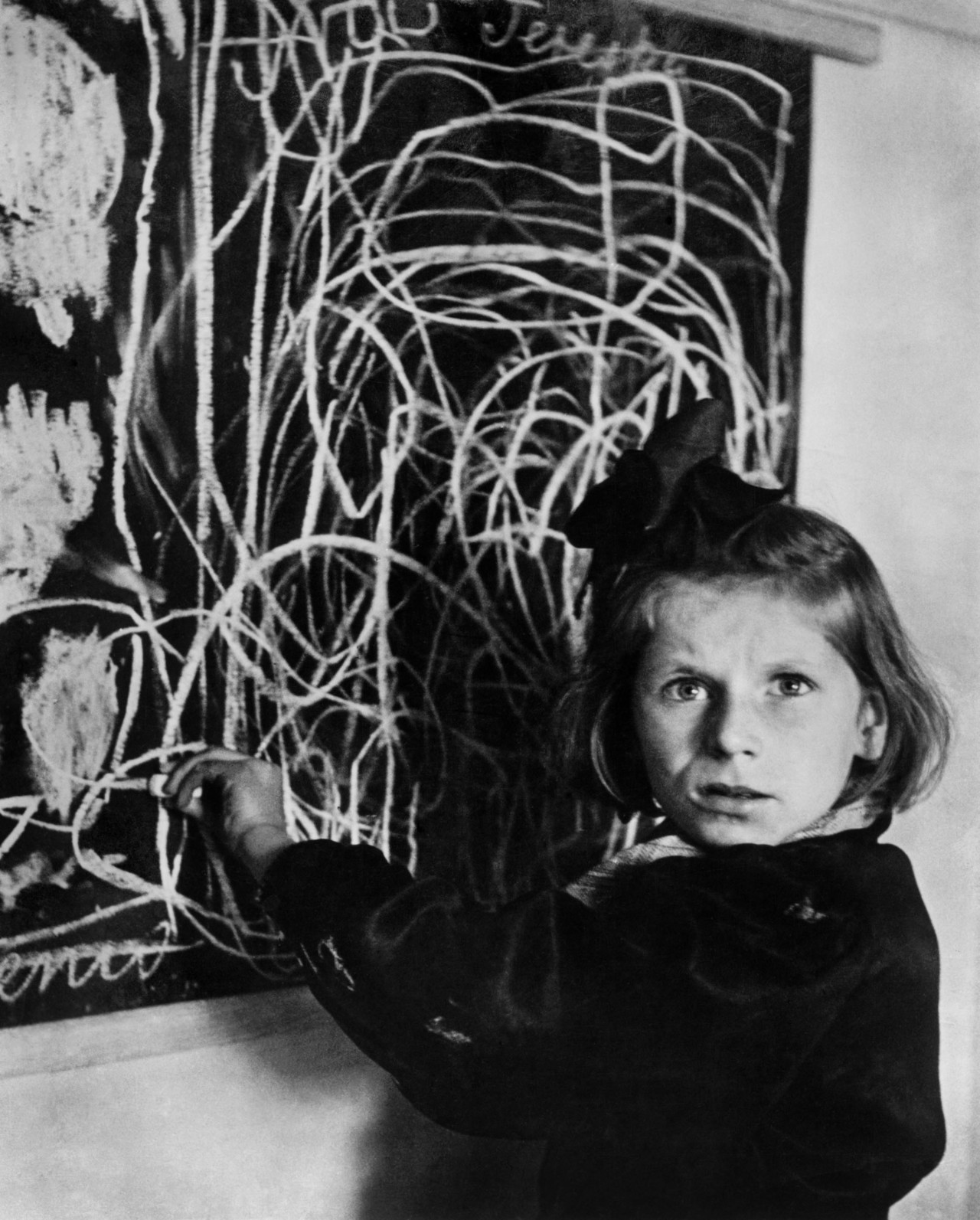

Chim’s postwar work was marked by a very important assignment in 1948 for the nascent UNICEF organization, Children of Europe. His war-time work had also found a place for children, often as a counterpoint to the scenes of death and destruction so often figuring in his images.

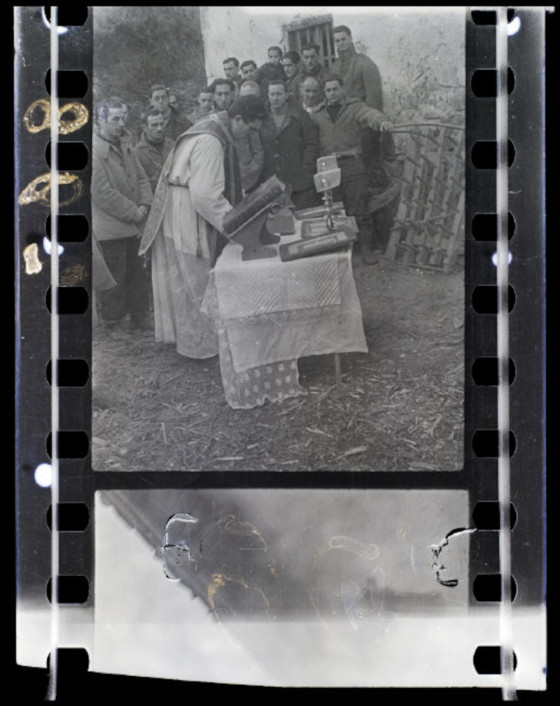

His approach to war photography seemed subtly different to that of Capa and Taro, being “thoughtful and analytical,” and often focusing on “life behind the scenes” of military action, concentrating more attention on civilians. Naggar’s careful reference to analysis of his notebooks, vintage prints and publications (as rediscovered in the long-lost ‘Mexican Suitcase’) reveals him to be to even more different than first thought, being “more secretive, more critical, more demanding of his own work.”

Naggar uses the careful recovery of Chim’s Spanish Civil War negatives from this source to demonstrate that his approach was, despite the pressures of war reportage, more careful and considered, and very precisely composed, as if he was taking more time to assess the pictures he wanted to make in his head before pressing the shutter release.

Although he was a well-published and proficient war photographer, the outbreak of World War II in 1939 would have another surprise in store for Chim: he did not return to Europe until the war was in its last throes, in 1944 when he had become a photo interpreter for the US military (and an American citizen now known as ‘David Seymour’). However, although he had his own cameras, his photographs from this period are mainly of personal subjects, without an assignment in sight.

The end of the war was a disturbing time, but Chim, now back in New York, would soon start to pick up new assignments. They included one from This Week magazine to document the progress of the US Army in Europe as war ended, and – unusually for him – it was to be mostly in color. By this time, a new agency – Magnum Photos – had been properly founded, with Capa, Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and Chim as its photographer directors, all of whom were about 40 years old. As Inge Bondi, who began work there in 1950, noted, “Chim and Capa both had the idea that they needed a community of like-minded people to flourish.”

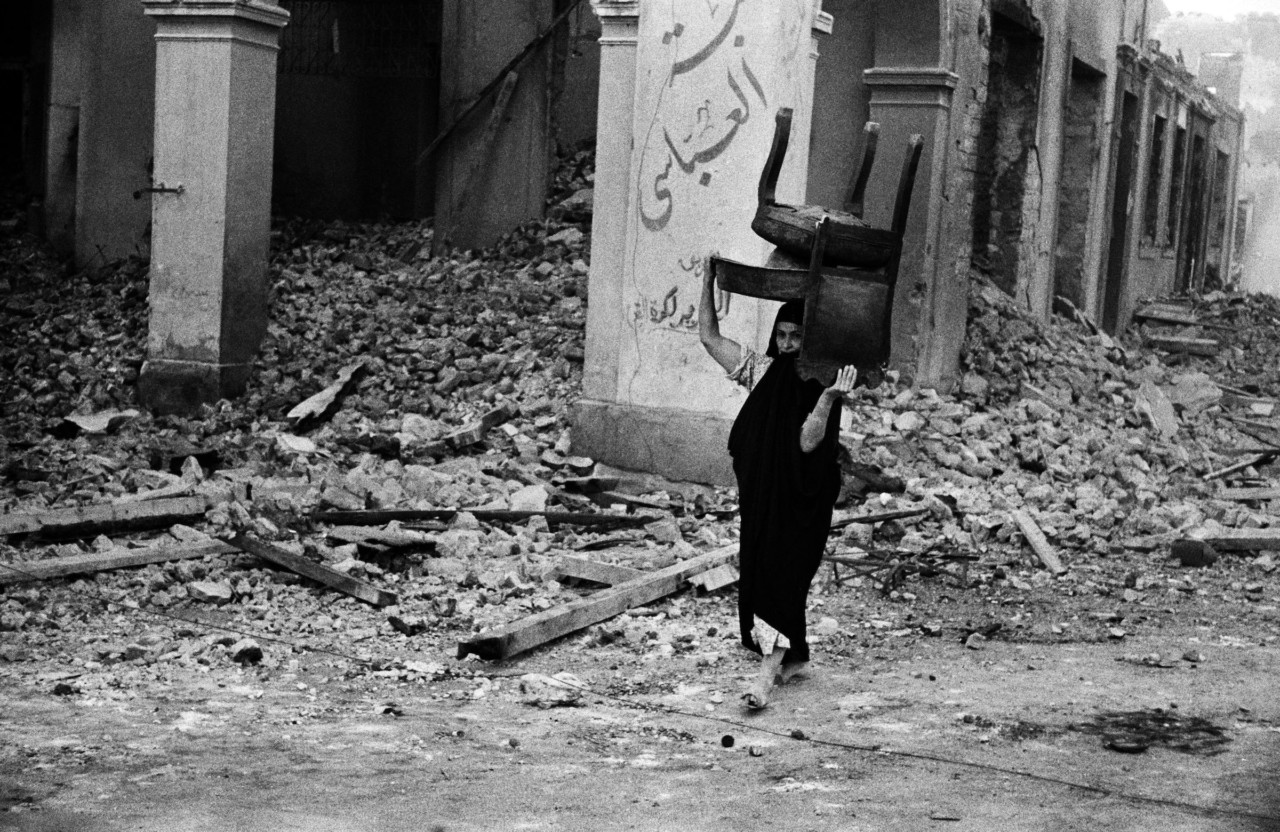

The rest, as they say, is history. Chim played his part in the organization of the new collective. Then, in 1956, the leader of Egypt, Colonel Nasser, suddenly seized control of the Suez Canal and nationalized it. Three months later, Israeli troops invaded. Chim wanted to cover it, though he had not been in a war zone since the end of World War II. He wanted to be involved in photographing the conflict, as he felt that Magnum “cannot stay out of world events,” and being in Greece, thought he was near enough to be able to get over fairly easily.

The Israeli invasion was rapidly followed by the involvement of Britain and France. This was eventually brought to an end by the arrival of a UN peace-keeping force and the pull-out of the British and French forces. On Friday, November 10, 1956, Chim and colleague Jean Roy, a reporter for Paris Match, had heard of a prisoner exchange at Al Quantara, the last post before the Egyptian lines. Although warned to be careful by a British officer, Chim and Roy drove towards the post despite further warnings from an outpost of French troops about the Egyptian soldiers being nervous.

Indeed, they were, and they opened fire. The jeep zigzagged and fell into the canal. Only three days after the ceasefire, both men were dead, their bodies riddled with bullets, Chim only 10 days from his 45th birthday. After a brief ceremony in Egypt, his body was flown back to the US and he was buried in New York.

As Naggar writes, though he was “an owlish, scholarly figure who would seem the antithesis of the heroic war photographer, Chim was killed in the Suez war of 1956, during a supposed ceasefire, when his jeep strayed through the Egyptian lines.”

Sixty-six years later, his spirit and the photographers’ collective he co-founded, still lives on as the world-renowned Magnum Photos agency.