Past Square Print Sale

Conditions of the Heart: on Empathy and Connection in Photography

Explorations of the notion of empathy and the vital connections between photographer, subject and audience by Magnum photographers

Inspired by Magnum co-founder David ‘Chim’ Seymour’s lasting legacy, Conditions of the Heart explores the notion of empathy and the vital connections between photographer, subject and audience. Explore the full slideshow of 72 images below, the sale here, and read more to uncover the connections at the heart of this project, spanning the classic and contemporary practices of Magnum photographers.

"Chim picked up his camera the way a doctor takes his stethoscope out of his bag, applying his diagnosis to the condition of the heart"

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

Magnum co-founder Chim is perhaps the least well-known of the four founders who, at the end of World War II, together created what has been described as the world’s most prestigious photo agency. Yet, his reportage work leaves an enduring legacy within the agency and the photographic community at large. Prolific during the Spanish Civil War (where he met Robert Capa) Chim remains best-known for his empathetic relationship to the refugee children he photographed in the wake of the war in Austria, Hungary, Poland, and Germany. Chim became President of Magnum Photos in 1954, after Capa’s death. Only two years later, he died in Egypt under machine gun fire. His engagement, the connections he created through his life and work, and his commitment to reporting on the important stories of his day, reflect a deeply-rooted belief in a collective sense of our own humanity which still imbues the agency’s spirit today, and which we explore in this Square Print project. “We are only trying to tell a story. Let the 17th-century painters worry about the effects. We’ve got to tell it now, let the news in, show the hungry face, the broken land, anything so that those who are comfortable may be moved a little.” —David ‘Chim’ Seymour

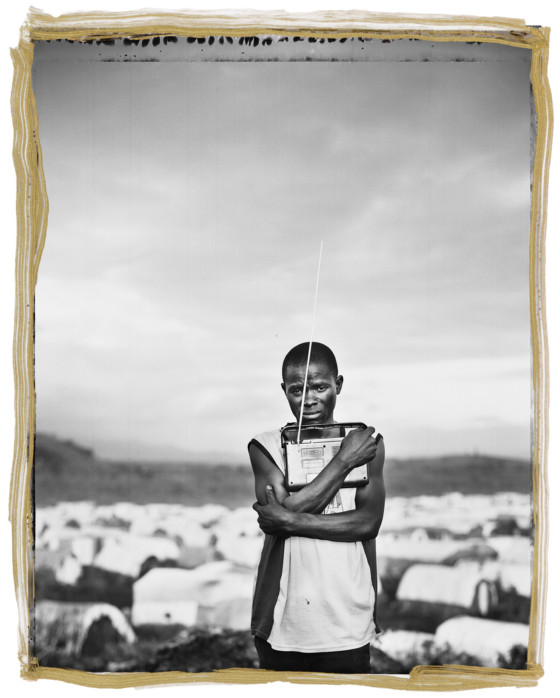

Connecting to our Fellow Man

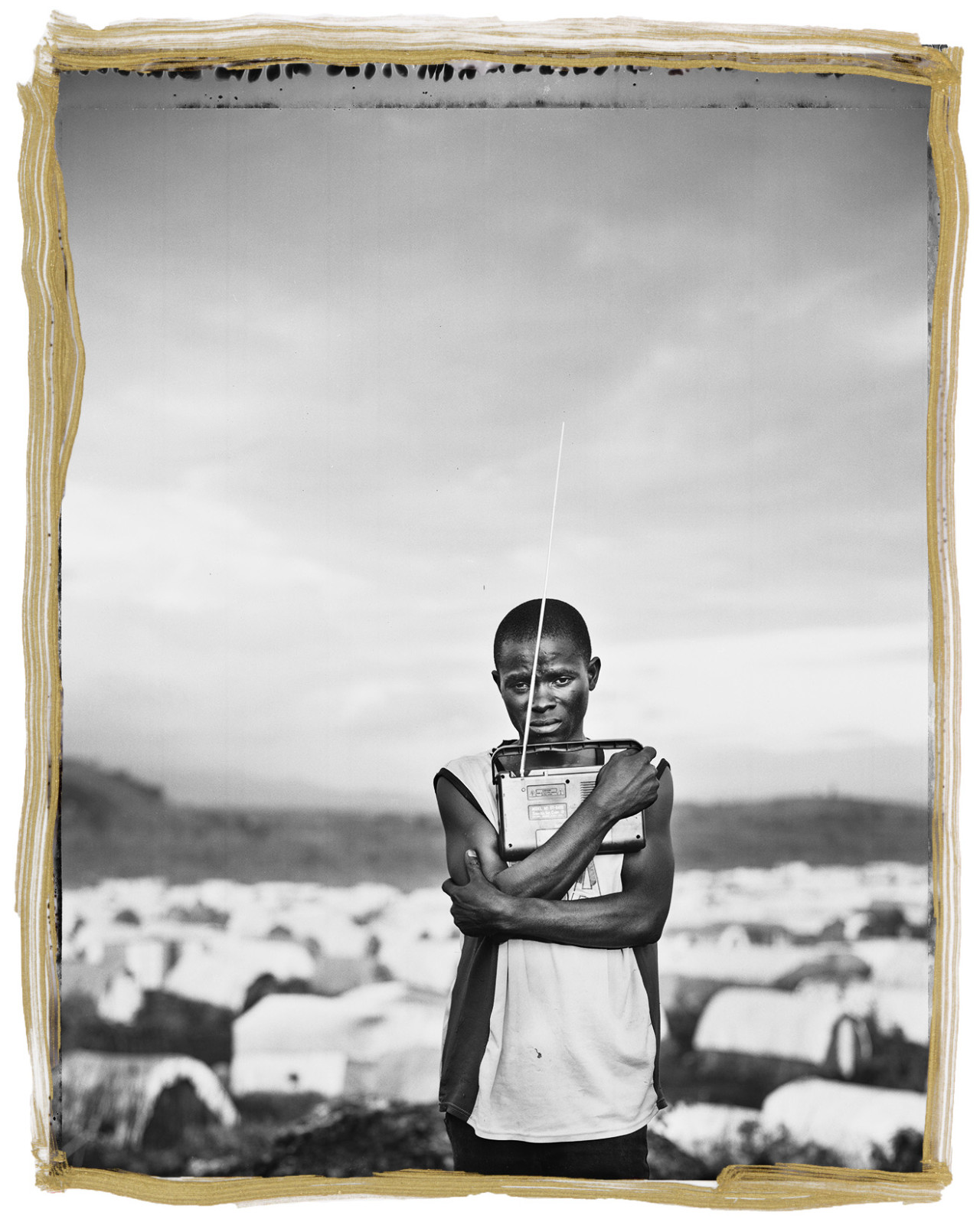

“Photojournalists are part of a continuous line that goes back to the Age of Exploration. They spread out across the world, seeking and discovering along the way. They are adventurers as the explorers of the past were. […] But they are not in search of treasure or new science. They are in search of moments that will connect us to our fellow man,” said Kathy Ryan, New York Times Magazine Director of Photography, in a speech at the W. Eugene Smith Grant Ceremony at the School of Visual Arts, on October 13, 2016. Jim Goldberg’s portrait of Wembe and his prized radio is a testimony to this deep need to connect our fellow men: a refugee at the Mugunga Refugee Camp, “Wembe had had this radio ever since escaping a rebel attack in his village, one year before. It was the only possession he was able to keep. Wembe told me that he climbed the hill every day to listen for good news.”

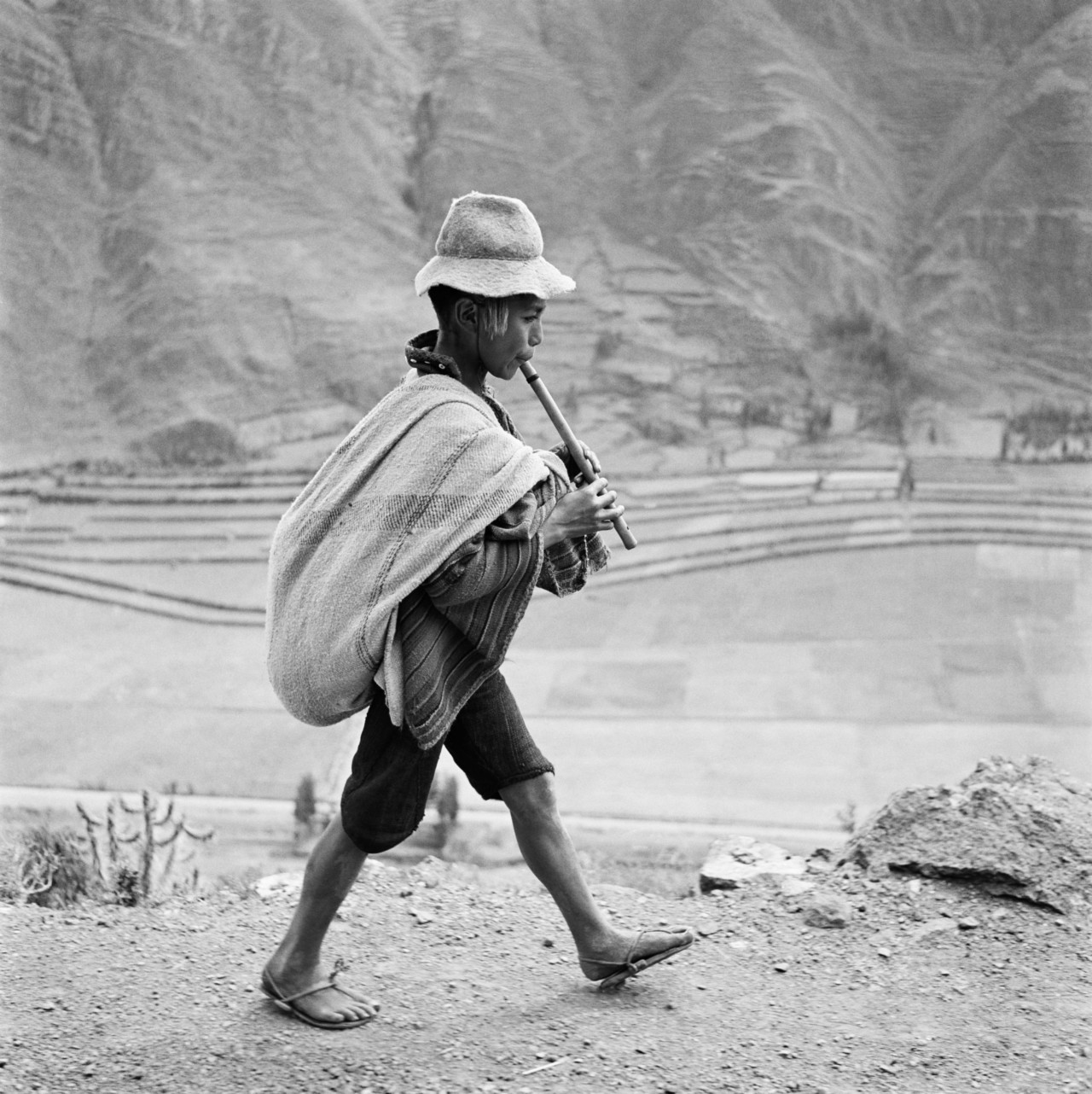

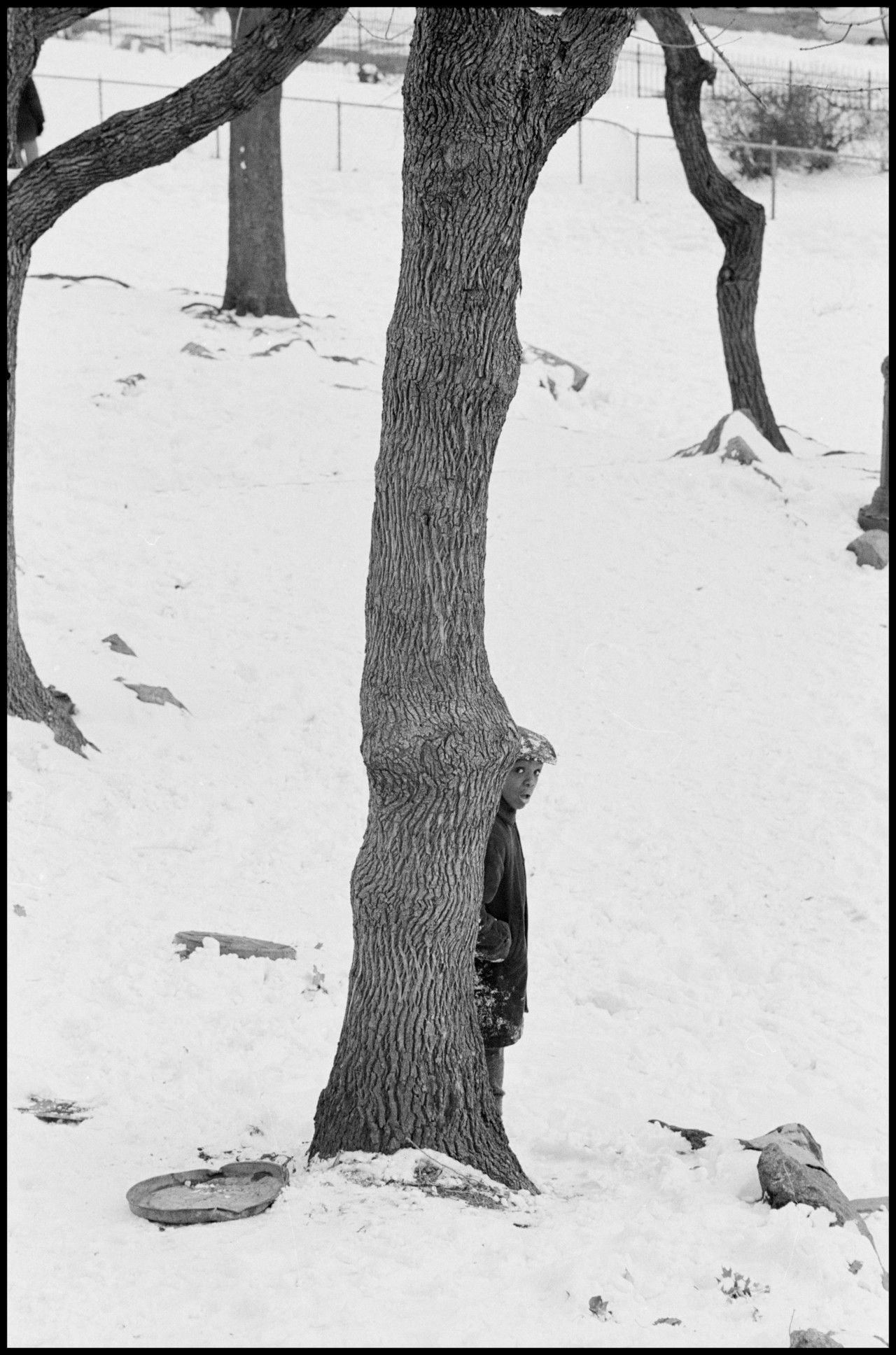

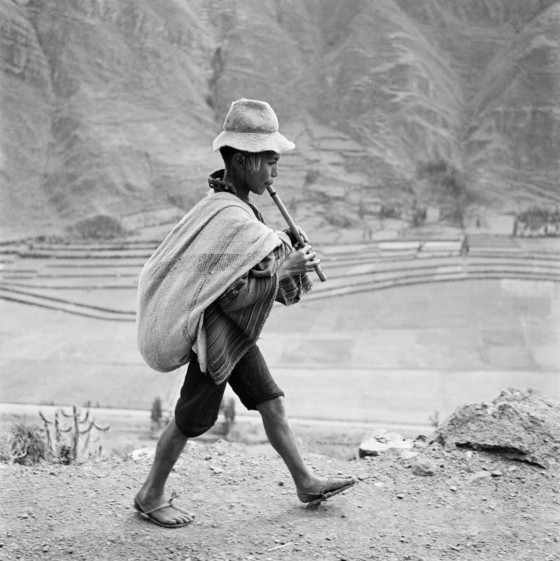

Werner Bischof’s advice was to take pictures with your heart; in this project we show the last picture taken by the photographer before his tragic death in the Andes. The flute-playing child echoes down the decades to resonate with other images of children in this selection: Eve Arnold’s photograph of a Cuban family living in poverty, so poor that they begged the photographer to adopt their child; Tim Hetherington’s longstanding relationship with the blind pupils of the Milton Margai School for the Blind, in Sierra Leone, who referred to him as ‘Uncle Tim’; Hiroji Kubota remembering a youth he photographed in Harlem in 1967; Herbert List buying the child in his photograph a bag of candy, a gesture which the young shepherd would remember forever. Cornell Capa is well-known for his adoption of the term ‘concerned photography’: “The Concerned Photographer produces images in which genuine human feeling predominates over commercial cynicism or disinterested formalism.”

The Responsibility of Representation

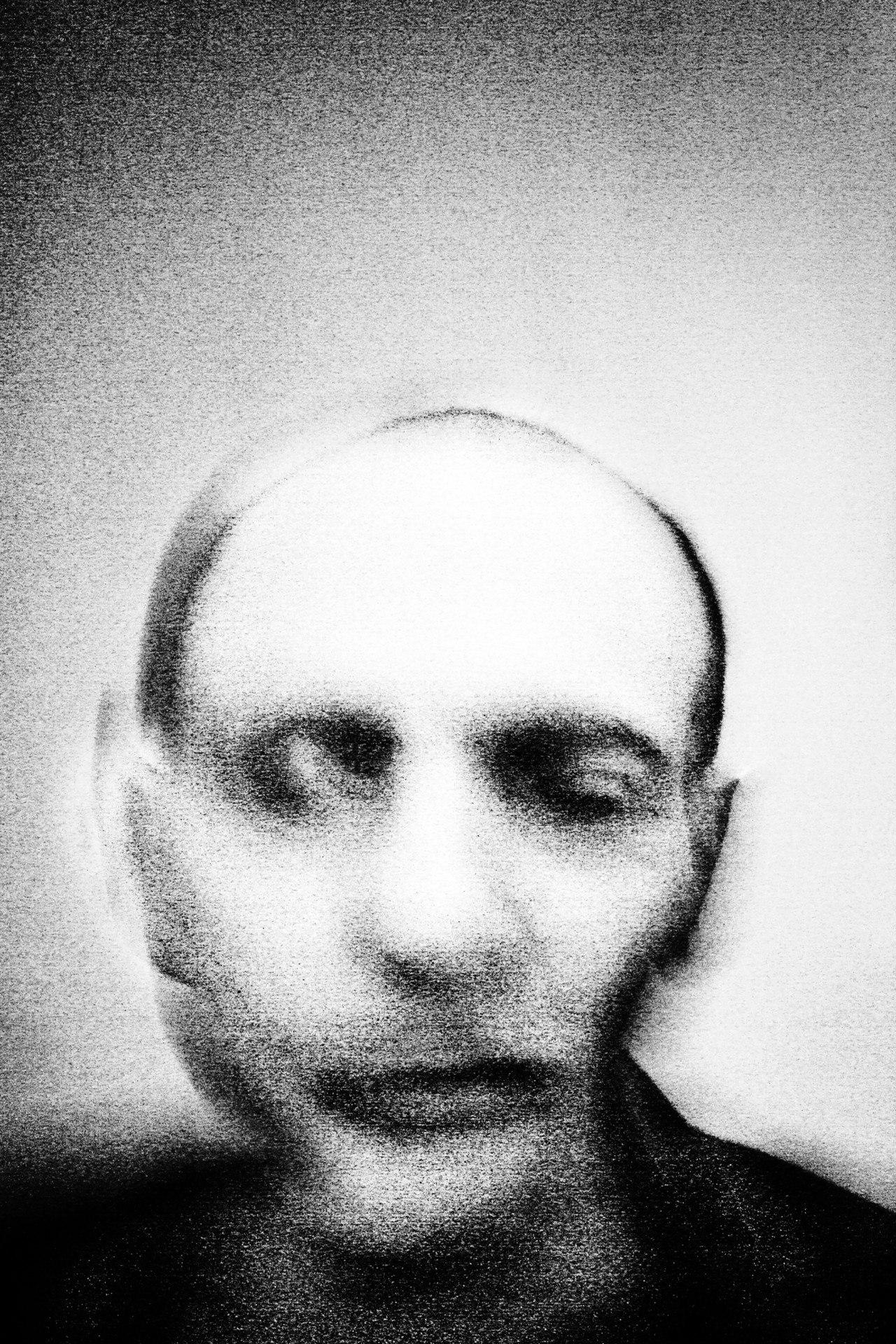

As Kathy Ryan noted in her speech, “pictures are intended to have consequences.” For some, there is a burden to being a photographer, the price to pay being that of a heightened sense of responsibility. Often “complete outsiders” to the situations they photograph (Jonas Bendiksen), the photographers have to make decisions about how, why and when they make the images they do, for these are the images that connect the subject and their viewers. For his portrait of Chuck Close, Chris Anderson notes, “I wanted to feel his presence in the image. I wanted to sense the passage of time on his face and his isolation, without actually seeing the wheelchair. Intimacy and empathy go hand in hand.” “A situation that one thinks might lead to feeling empathy can instead leave one feeling detached and alienated. But sometimes, a fleeting moment caught just from the corner of the eye draws you in and connects you. It cannot be planned or managed. Good photographs are the same,” says Matt Black, whose Geography of Poverty project endeavours to comprehensively document high poverty areas in the USA.

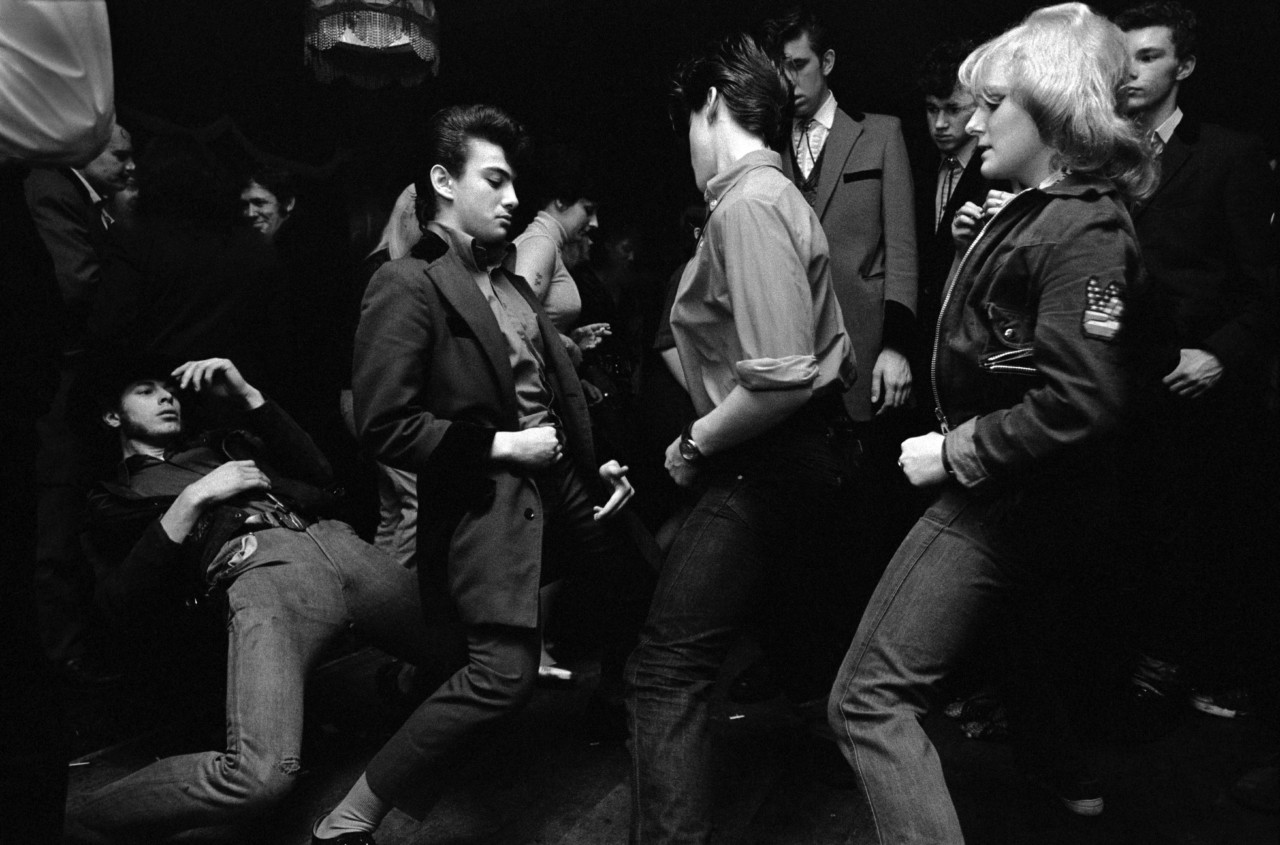

Embarking on long-term projects, photographers spend long periods of time in a region or documenting a specific issue, such as Michael Christopher Brown has done in the Congo. His optimism for the future fate of the country shines through his portrait of a young sheep herder. “I have always wondered if photographing without empathy is even possible,” asks John Vink. Chris Steele-Perkins, who documented the British ‘Teddy Boys’ for many years, writes “All of my working life I’ve been drawn to subcultures, small worlds which have the whole world in them.” These long-term investigations are deeply rooted in the agency’s DNA.

Witnessing History

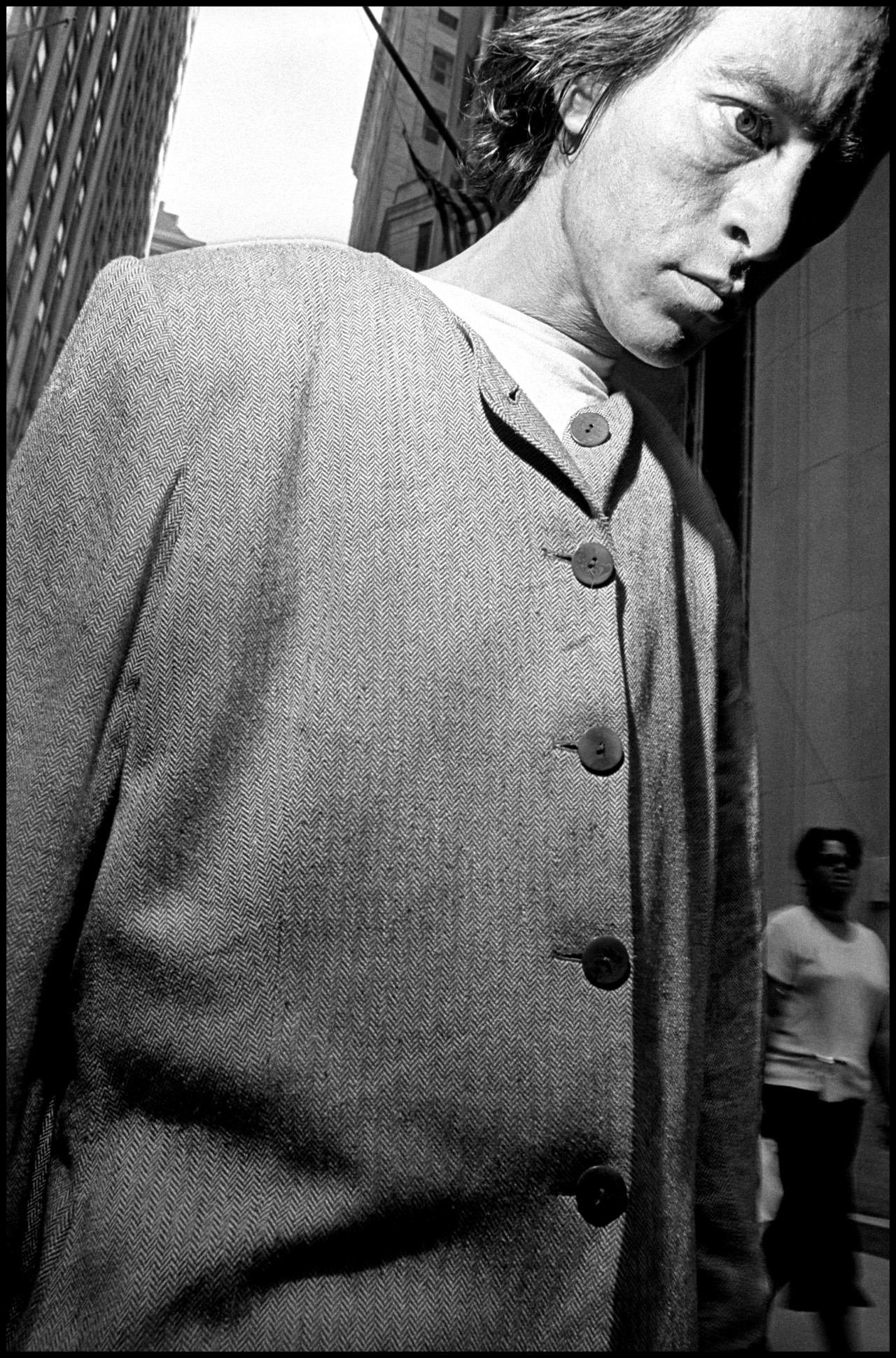

“When I do my work and I’m exposed to the suffering of others – their loss or, at times, their death – I feel I am acting as a witness; my role and responsibility is to create a record for our collective memory,” writes Paolo Pellegrin. From Micha Bar-Am’s emotive image of the moment of safe arrival of freed hostages from a Paris – Tel-Aviv flight to Bruce Gilden photographing people on the day Wall Street reopened after 9/11, the need to record, to communicate through images, without language, yields important documents that become icons of our shared history.

Robert Capa’s portrait of Gunnar Moe, a Generation X boy, speaks to his early recognition of the disenchantment and fatalism of the post-war generation.

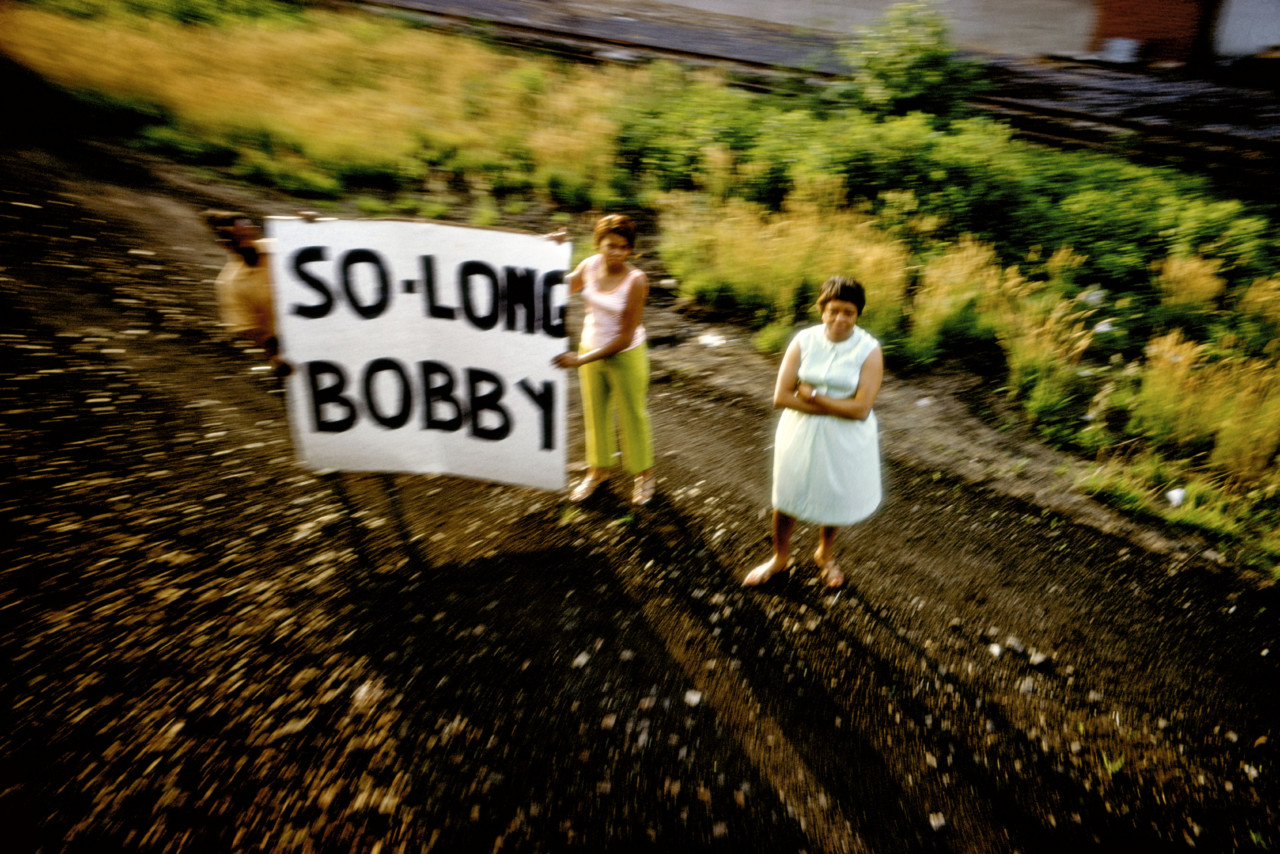

Eli Reed’s portrait of President Obama is an image which for the photographer elicits a kinship of feeling as two pioneering African-American men. Paul Fusco’s photograph taken from Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral train captures some of the 2 million or so people who came to witness its passage, waving a last farewell to the much-beloved president.

Leonard Freed’s image embodies a silent connection between an American photographer and an American soldier guarding the Berlin Wall, in 1961, an image which went on to become the introductory photograph of his Black in White America book and, spanning cultures and continents, is displayed both at the Checkpoint Charlie Museum in Berlin and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C. Thomas Hoepker also recalls the Berlin Wall for this project, photographing the children who played in its vicinity, oblivious to the disconnection the Wall embodied: “children on the western side used the ugly edifice as a playground. They climbed up to take a peek of the other side or bounced their football against the bricks.” Early documenter of the Civil Rights movement Bruce Davidson says of the power of photographs: “Sometimes they don’t tell stories, they simply speak as images. They express feeling, increase knowledge. Photographs can draw passion, beauty and understanding. And then there is love.”

Family and Other Animals

Eugene Smith once said: “The journalistic photographer can have no other than a personal approach; and it is impossible for him to be completely objective.” The intimate bonds shaped by familial relationships provide the backdrop for some of the photographers’ most personal work. Alec Soth shares an image from his project Dog Days, Bogota, where he spent two months waiting for his daughter’s adoption papers to be processed by the Colombian court, so that he would be able to take his daughter home. Of his image of a small dog, he writes, “During my long walks I regularly encountered homeless children. Seeing these kids was a profound part of my experience, but I couldn’t bring myself to make pictures. I suppose my feeling of connection with my new daughter overwhelmed my desire to be a photographer. As a substitute for the kids, I photographed the city’s many homeless dogs.”

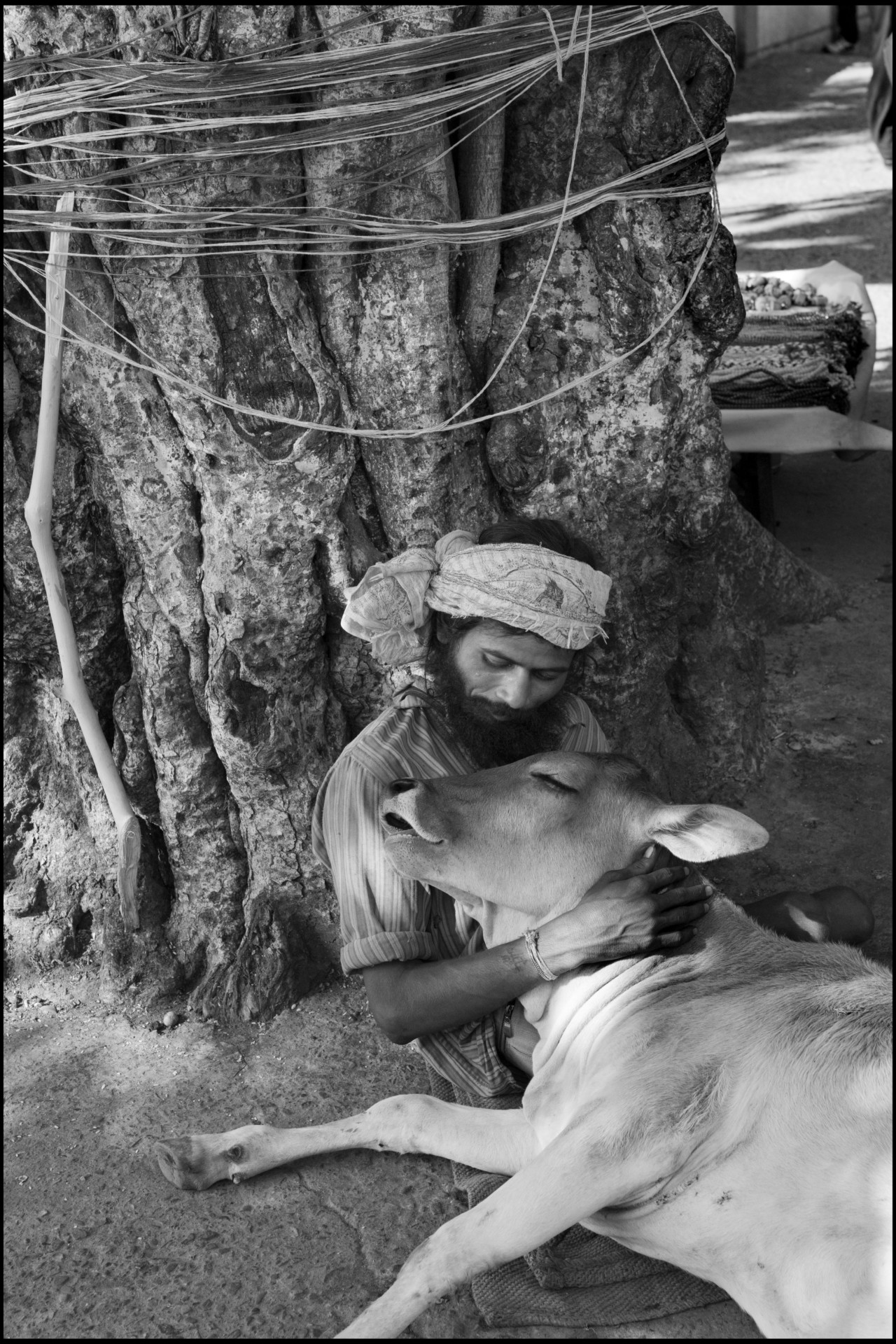

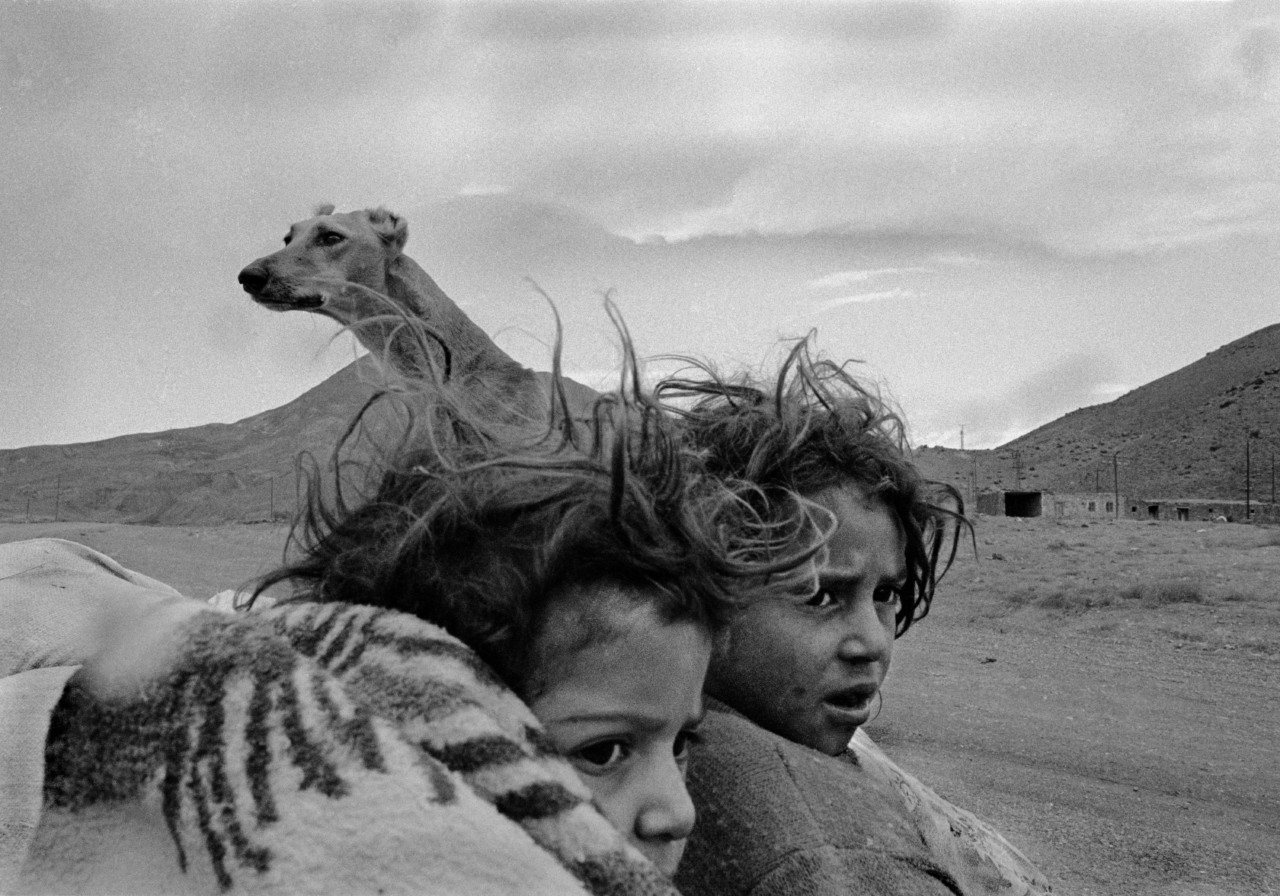

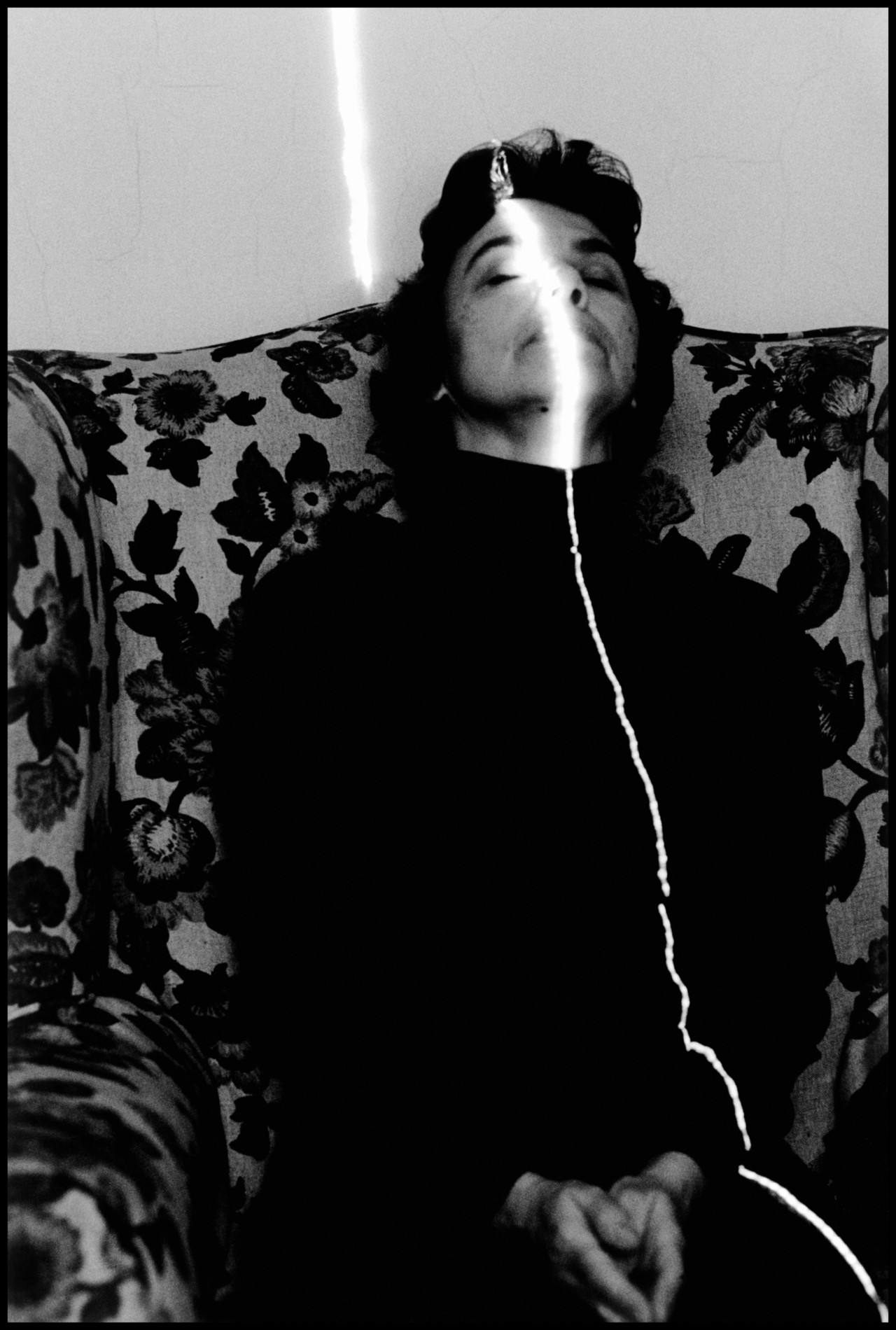

Harry Gruyaert’s vivid of photograph of his daughter lit by Venetian sunlight, Wayne Miller photographing his son David in robot costume on his way to school, or Erich Hartmann playing with lasers to create an experimental portrait of his wife Ruth (who lives to tell the tale for this photographer’s contribution to the project), all speak to the bonds that bind humans together. Intimate connections such as the sisterly dynamic captured by Olivia Arthur or Peter van Agtmael’s photograph of a war veteran and his kids playing represent the appeal of this universal connection to the other. “Sometimes I mark time through this photograph,” says Peter van Agtmael. And sometimes, the bonds between humans and their animals are just as strong as these bonds, as shown in Jacob Aue Sobol’s or Steve McCurry’s photographs.

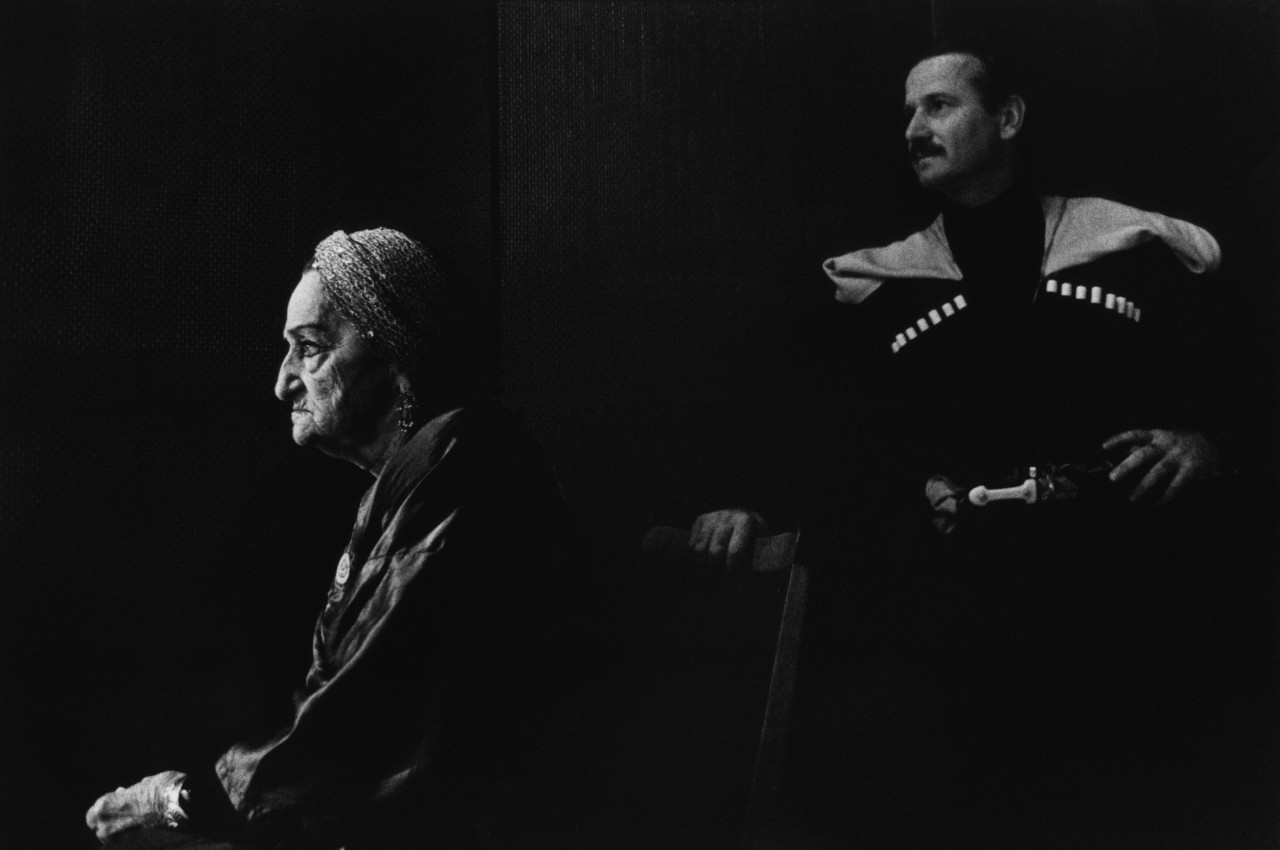

In Diana Markosian’s personal quest to find her father, she speaks to the capacity photography has to help forge these bonds: “My work often deals with memory, time and things that aren’t visually descriptive. This image was taken at my father’s home. We were separated when I was seven, and it took me fifteen years to find him in Armenia. I don’t think photography can ever bridge that gap between us, but it has allowed us to confront our past, to be vulnerable, in the process of building a relationship together.”

Elliott Erwitt sums it up with his pithy aphorism: “The ability to understand and share the feelings of another is the reason everyone should have a dog.”

Connecting Places

From Mark Power’s “passionate love affair” with Poland to Jerome Sessini’s “close connection” to Mexico, a deeply-rooted sense of connection is often borne out of a photographer’s relationship to a place. Nikos Economopoulos’s trips to Turkey or Thomas Dworzak, whose image is a “toast to the Caucasus”, a region he has photographed almost obsessively, are testament to this. “Connection in photography can take many forms. While one typically thinks of the connection in photographing people one knows, there can also be a kind of intimacy with a place or a culture itself. As a street photographer, it is this latter connection that intrigues me,” says Alex Webb.

Similarly, on photographing Morocco, Bruno Barbey said, “Here, it is sometimes so difficult for a photographer to do his job that he must learn to merge into the walls. Photos must either be taken swiftly, with all the attendant risks, or only after long periods of infinite patience…” Donovan Wylie is known for his recursive work on places and spaces. Steve McCurry’s vivid images of faraway destinations have graced the pages of many National Geographic magazines. Matt Black travels the length and breadth of America for his project. Stuart Franklin has poetic relationship to the landscapes he photographs, seeing our humanity reflected in them: “I’m interested in the nature-society phenomenon, the way in which we anthropomorphize aspects of the landscape and see ourselves reflected in it or as shadows across it.”

Cultural Connections

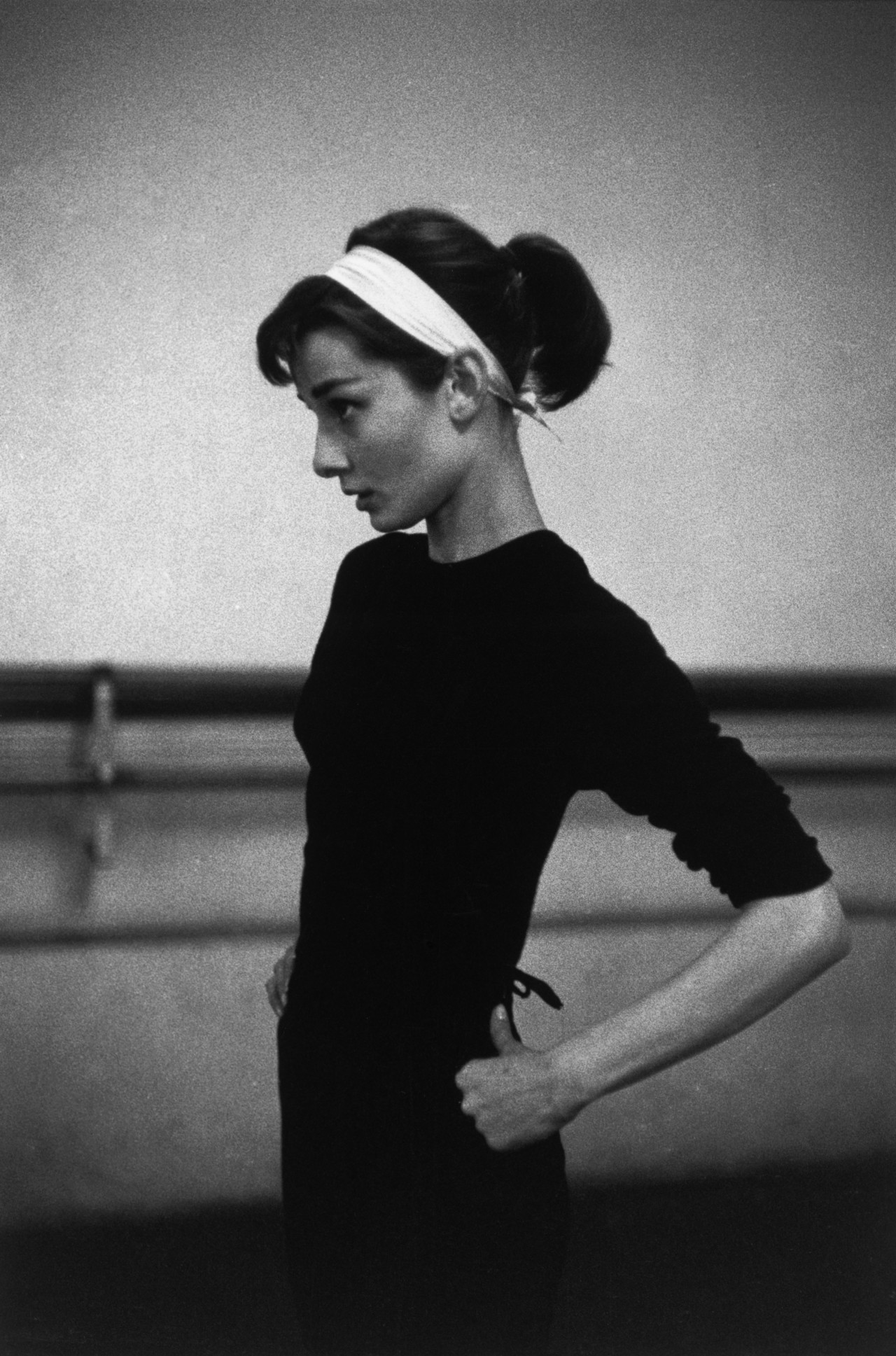

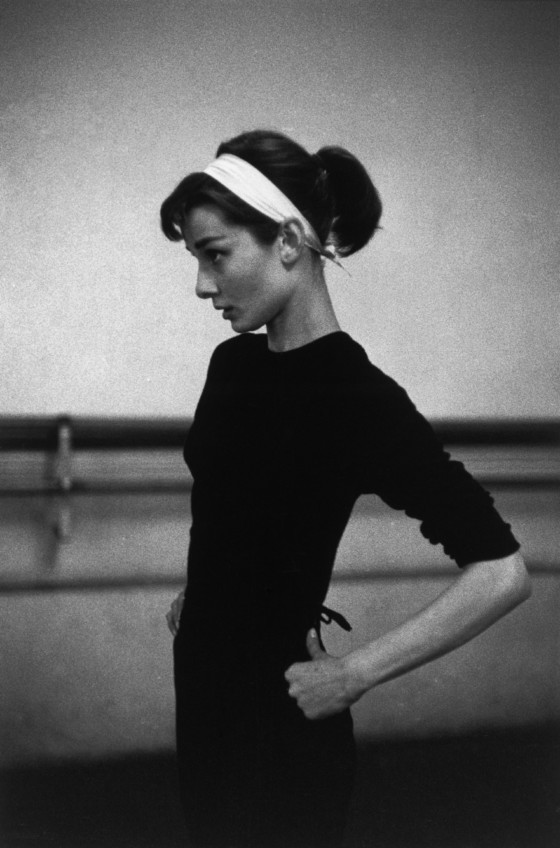

“Chim’s capacity to connect with people, and indeed humanize them, also translated to Hollywood superstars… This tranquil moment shows Audrey Hepburn in deep concentration at a ballet studio. Chim captured her quiet intensity, self-confidence and graceful composure,” says Ben Shneiderman, nephew of David Seymour. Magnum photographers often have interesting and longstanding creative relationships with their cultural landscapes, photographing writers, thinkers, actors, and musicians, their experience in the field serving them well.

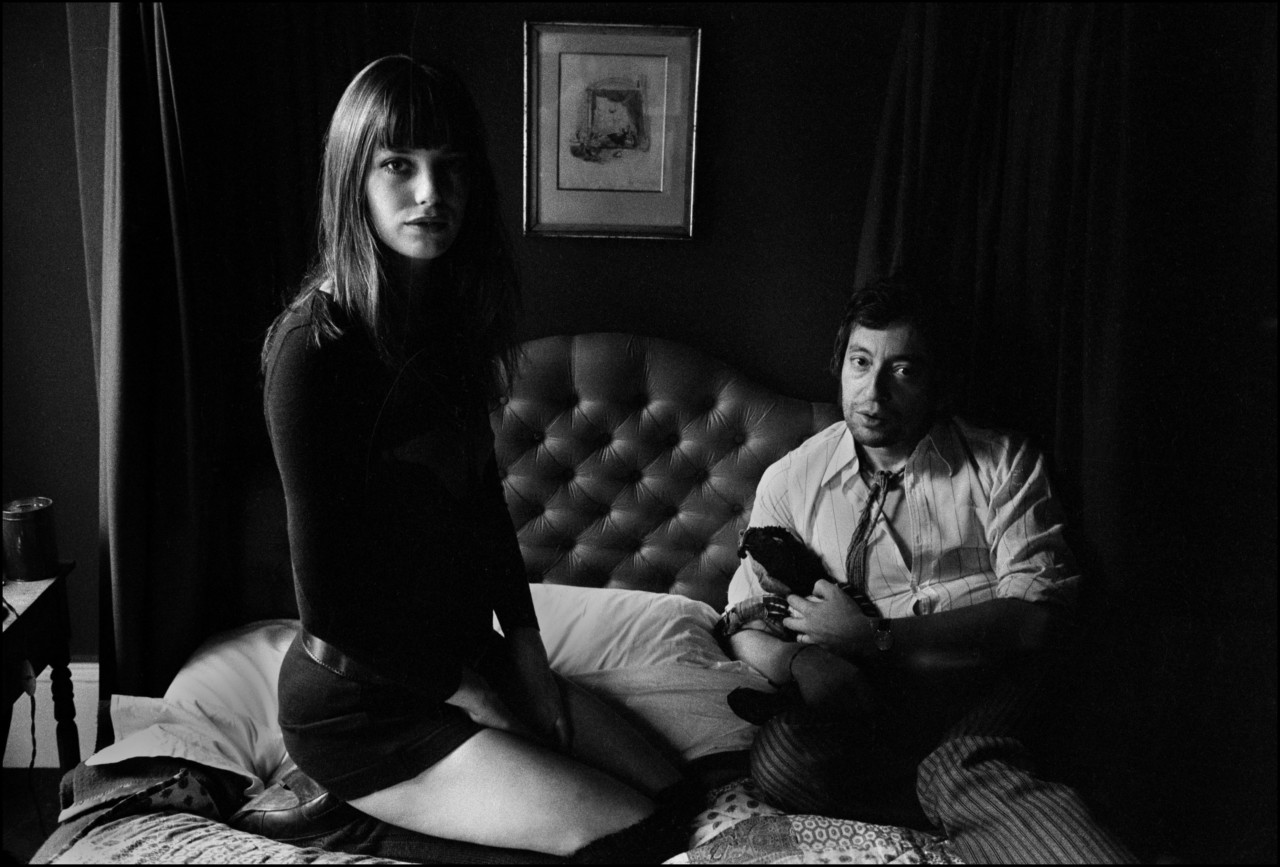

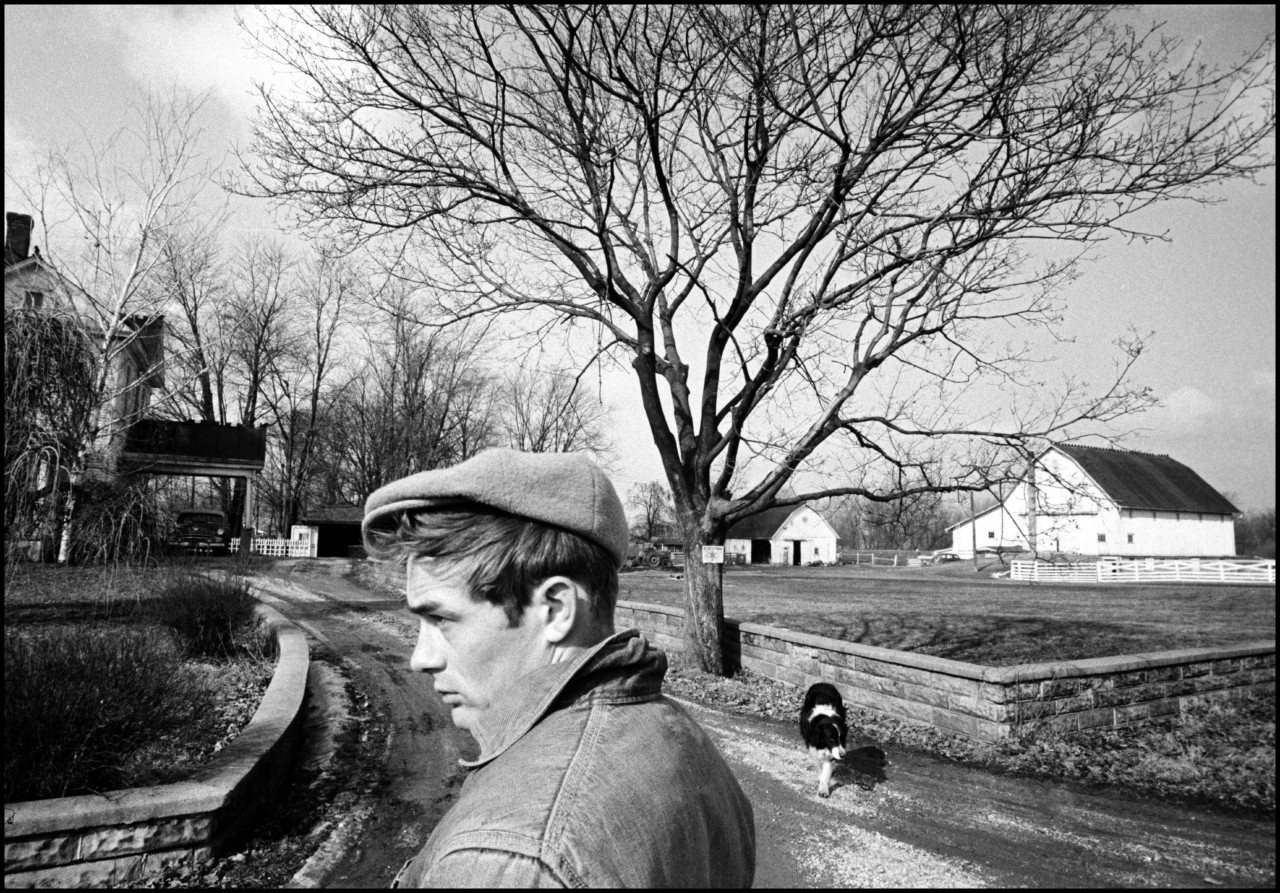

Dennis Stock’s portraits of James Dean are some of the most recognised images of the actor, but his early photograph of Dean at home marks a fleeting moment of transition. “There is a moment when we are not quite sure where our place in the world is, though we all must undertake the search to find it. Dennis has captured this moment. Perhaps this is why this photograph was one of his favorite images of James Dean; in fact, he often said it was his best-composed photo,” writes Susan Richards, wife of the photographer. In 1970, Ian Berry photographed Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin: “I spent the whole day with them, and they were totally relaxed, obviously in a great relationship. They attempted in no way to direct or influence what I was shooting, which made my life very easy.” When Inge Morath photographed Marilyn Monroe on the set of The Misfits, she waited patiently for the rare moment when the hyper-aware star wasn’t actively posing, to capture a single and subtly vulnerable shot of the actress, as what she called “the unposed person”.

Connected Moments

Kathy Ryan notes, “photographers have committed themselves to telling the stories of others. They cannot just stand by and watch the turmoil going on in the world today. They need to explore it and make sense of it. They have the clarity of vision and the purity of heart to do so.” Moises Saman survived a helicopter crash, and, once on board a second helicopter, took a picture of his fellow survivors inside, “almost unconsciously” photographing a shared near-death experience, which electrified his sense of being alive. This experience prompts him to write, “I had adhered to a false sense of distance from my subject, one that allowed for the pursuit of a sort of superficial creativity over genuine empathy. I was simply trying too hard.”

This immediacy speaks to the power of photography to create lasting connections. Another long-term project, Susan Meiselas’ Prince Street Girls project encapsulates many years of friendship between New York Italian women, but also serves as an anchoring point in the photographer’s life: ”It was important for me to keep on photographing them as they grew up, especially when I came back from abroad where I had been photographing wars. Looking at these pictures now reminds me of how difficult it was to integrate my two lives – family and friends at home, and my life as a photographer on the road. It was often a painful separation, though not one I regret having chosen.”

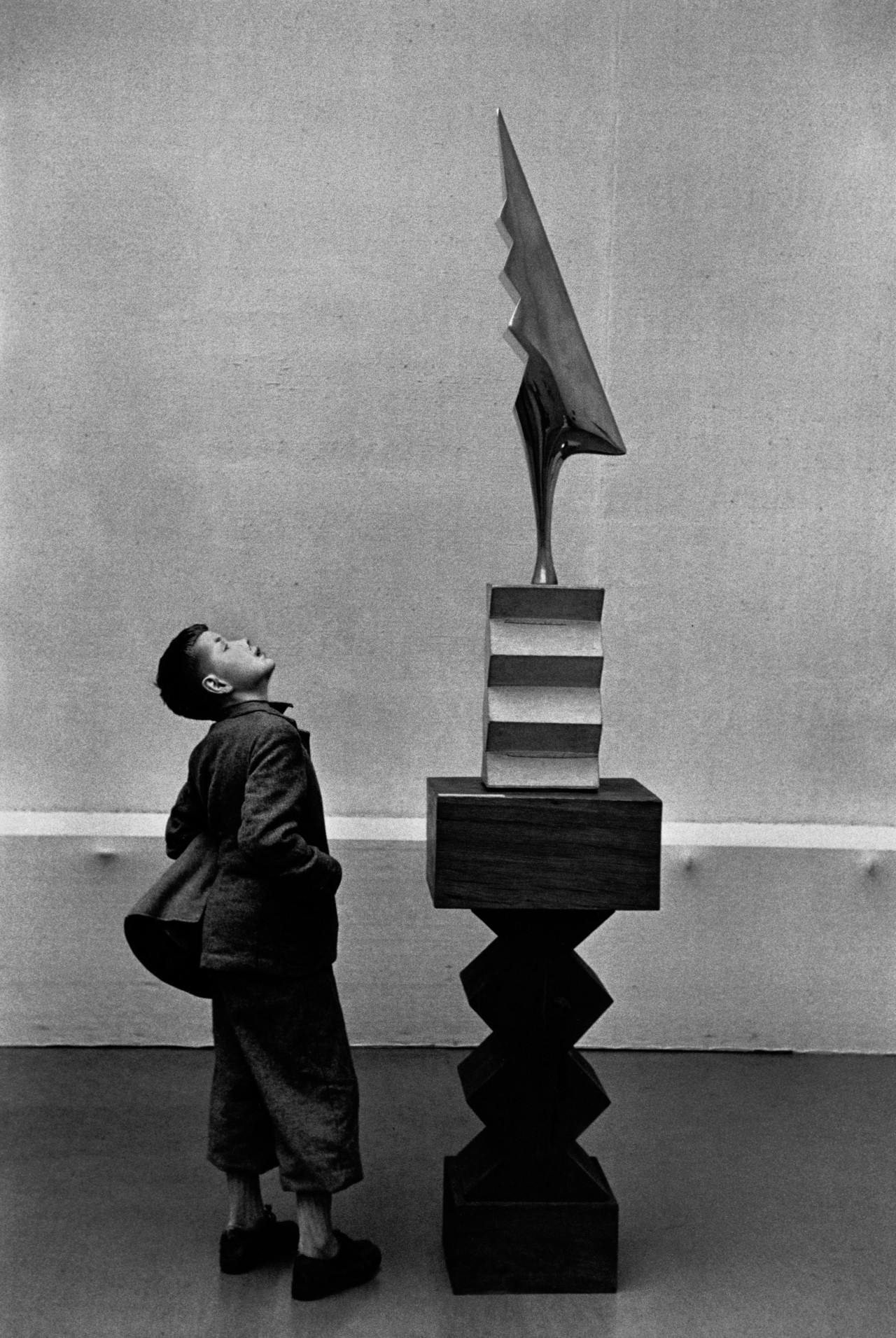

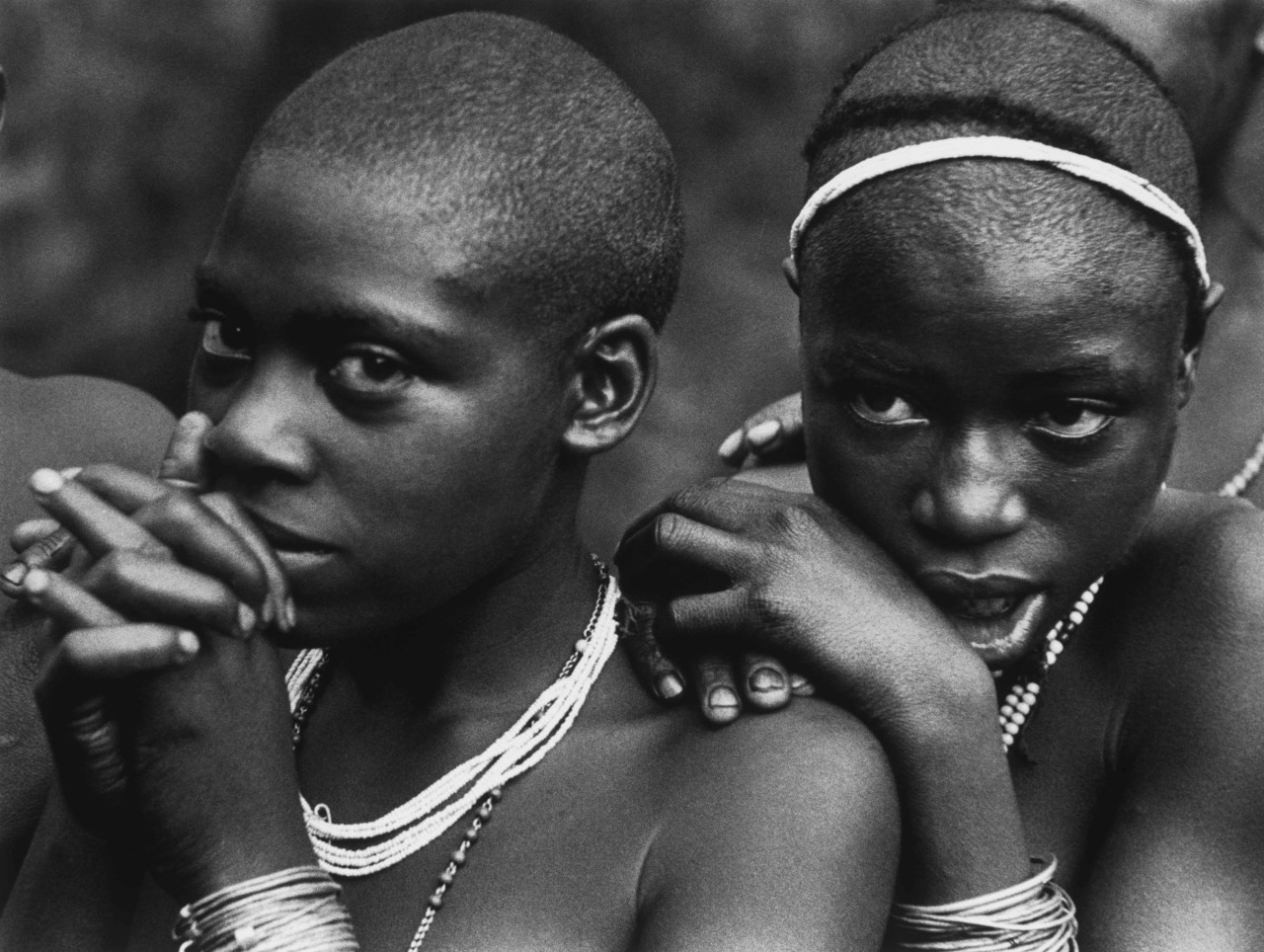

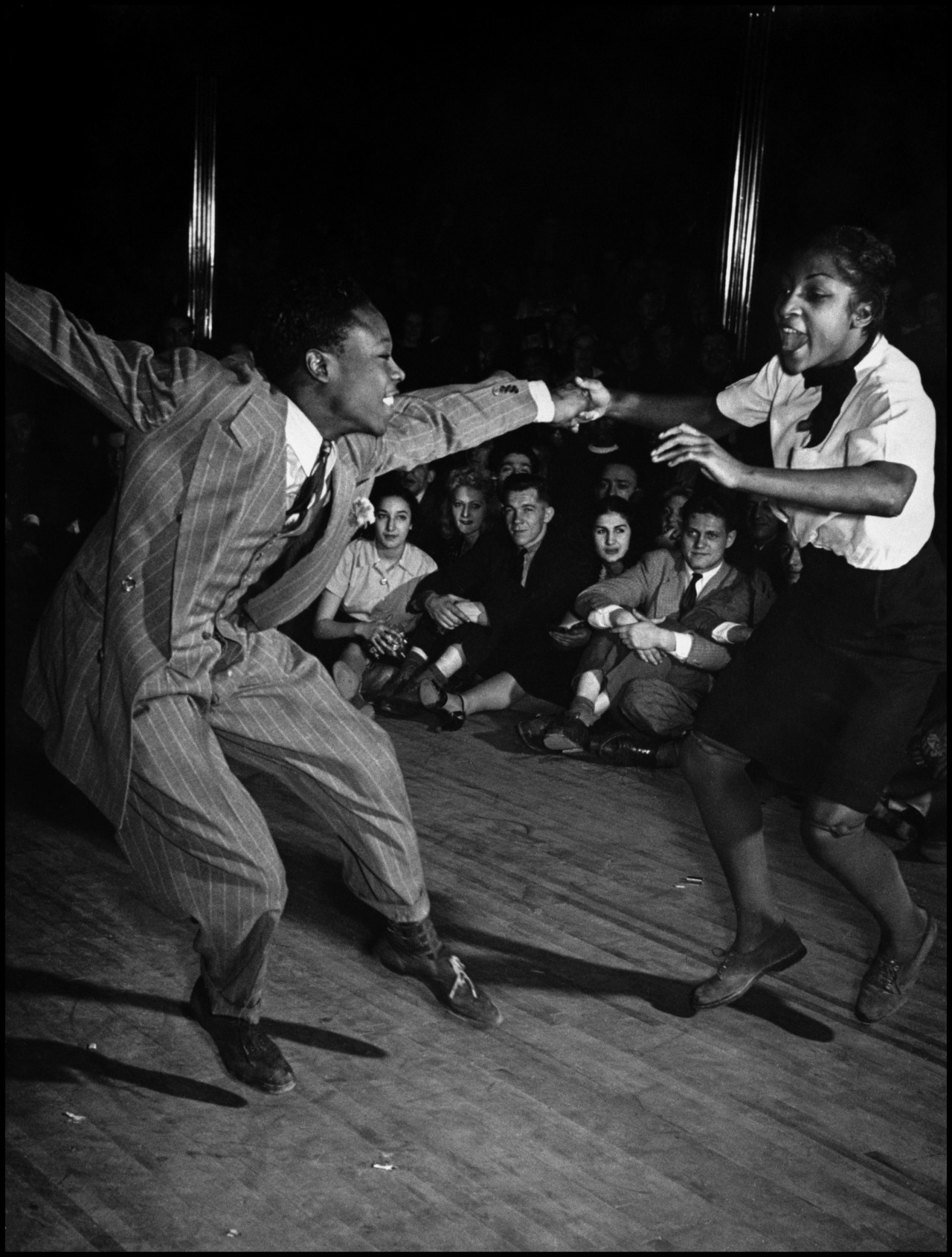

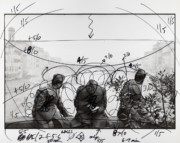

These fleeting moments create lasting connections that echo still today: Patrick Zachmann photographing a lone ice cream seller in the middle of the Atacama desert; the empathy and welcome shown George Rodger by the Nuba and Dinka tribes in 1949; Rene Burri’s photo of a little boy gazing up at a statue by Brancusi, capturing a fleeting moment of pure, distilled connection between child and art; two men captured mid-digestion by Richard Kalvar; Matt Stuart’s ground level view; David Alan Harvey photographing a gang of Parisian teenagers on the cusp between adolescence and adulthood.

Jean Gaumy describes his encounter with a weary, sea-wizened Spanish fisherman as total understanding without need for a common language. The connection between the young cheerleader and her sweetheart football player remains frozen in time in Burt Glinn’s photograph, a testament to his long documentation of the city of Seattle for LIFE in the 1950s.

Photographic Connections

In many ways this project reveals the relationship between the photographers and their connections to photography. Bieke Depoorter, whose contribution to the project is the single image that made her realise what photography meant to her, describes the moments she shared with her subject, just before taking the picture: “Without saying a word, she took me under her arm, brought me to her tiny house, fed me and showed me how to wash myself in a little basket. Still arm in arm, still in silence, we then went for the most peaceful walk I had ever taken.” In the same way, Alessandra Sanguinetti’s contribution speaks to the act of photography itself, revealing how it can shed light on the self: “I was a kid then, but I’m still making those same pictures.”

Newsha Tavakolian reveals her working process: “When I take a camera in my hand, the world around me slows down. As do I. I love to work slowly, to have time. People, in an event like the one in this picture, will start to trust me in this way, which allows me to blend in.” Trent Parke highlights the power of emotion and imagination in making his work: “I take documentary photographs and turn them into something else. They are what they are, but when they come into my world, I place them into different contexts. Nothing is ever what it seems to be.” Max Pinckers, ultimately, leaves it in the hands of his viewers, creating the conditions in his work for the “viewer to form their own interpretation of the scene.”

Pinkhassov defines empathy as “that rare point of intersection between ethics and aesthetics” – the photographs in this Square Print project, indeed, weave a path between visual representation and duty to record, between emotion and fact; dualities overcome by the power of the image to connect us in our shared humanity.