“History is what’s written, my pictures are what happened”

Diane Smyth speaks to former friends and colleagues of Chris Killip, whose estate is now represented by Magnum Photos, as a retrospective goes on show at The Photographers' Gallery in London, accompanied by a major new monograph published by Thames & Hudson.

I interviewed Chris Killip a few times and, despite his reputation as one of the most influential photographers of his generation, I always felt he was someone I could easily relate to. I thought this might be because he, like my mother, was born on the Isle of Man in the mid-1940s. But very many people became close to him over the years, from his colleagues in the early days of Side Gallery in Newcastle, near to where he made so much of his most iconic work in the North East of England in the 1970s and 80s, to his photography students at Harvard University in the US, where he taught for more than 25 years up until his retirement in 2017.

Most striking of all are his long relationships with the people he photographed, some of whom he stayed in touch with for decades. My feeling was less about a shared connection to a small island in the Irish Sea than about Killip’s empathy for others.

During one of our conversations, he told me that the thing that made him most proud was seeing his photographs in his subjects’ homes, up on their walls or in their family albums. He once asked Gregory Halpern, one of his former students at Harvard who became a friend and is now an associate at Magnum, if he ever visited the people he’d photographed without his camera.

“I remember being a bit startled by the question, and slightly ashamed,” writes Halpern in Chris Killip, a new book published by Thames & Hudson alongside a retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery in London that opens today (October 7) and runs until February 19, 2023. “Going back without my camera hadn’t occurred to me.

“My notion of a great photographer at that point was something akin to an explorer, whose success was measured by how well they extracted images,” Halpern continues. “Chris, of course, had a very different idea of how to measure a photographer’s success, and spent a lot of his time talking about things that were bigger than photography. He spent a lifetime photographing in places where he had built relationships, where there was trust and respect.”

It’s a more nuanced way of thinking about Killip and his work, for so long defined by one extraordinary book, In Flagrante. Published in 1988, this coruscating vision of the effects of de-industrialization in the North East of England is often cited among the greatest photobooks of the 20th century. And rightfully so.

But it’s also a book of just 50 photographs, selected from thousands more shot between 1975 to 1987. A deeper dive into Killip’s work and life reveals the longterm commitment that went into making those images, and so many more.

“I was really taken by In Flagrante,” Susan Meiselas tells me, “and looking back at it, it’s because I felt that deeply lived experience in the place – his connection to that community of which he was a part.

“A gifted photographer can go someplace and see a world they don’t come from,” she adds. “But there is this tension that when you belong, or you stay, or the more you live within a community, the more you see in a subtle way. I think you feel that with In Flagrante. You feel it in some of the expressions, the gestures, particularly because of the [large] format Chris was using. He’s very positioned, there’s no feeling of passing through.”

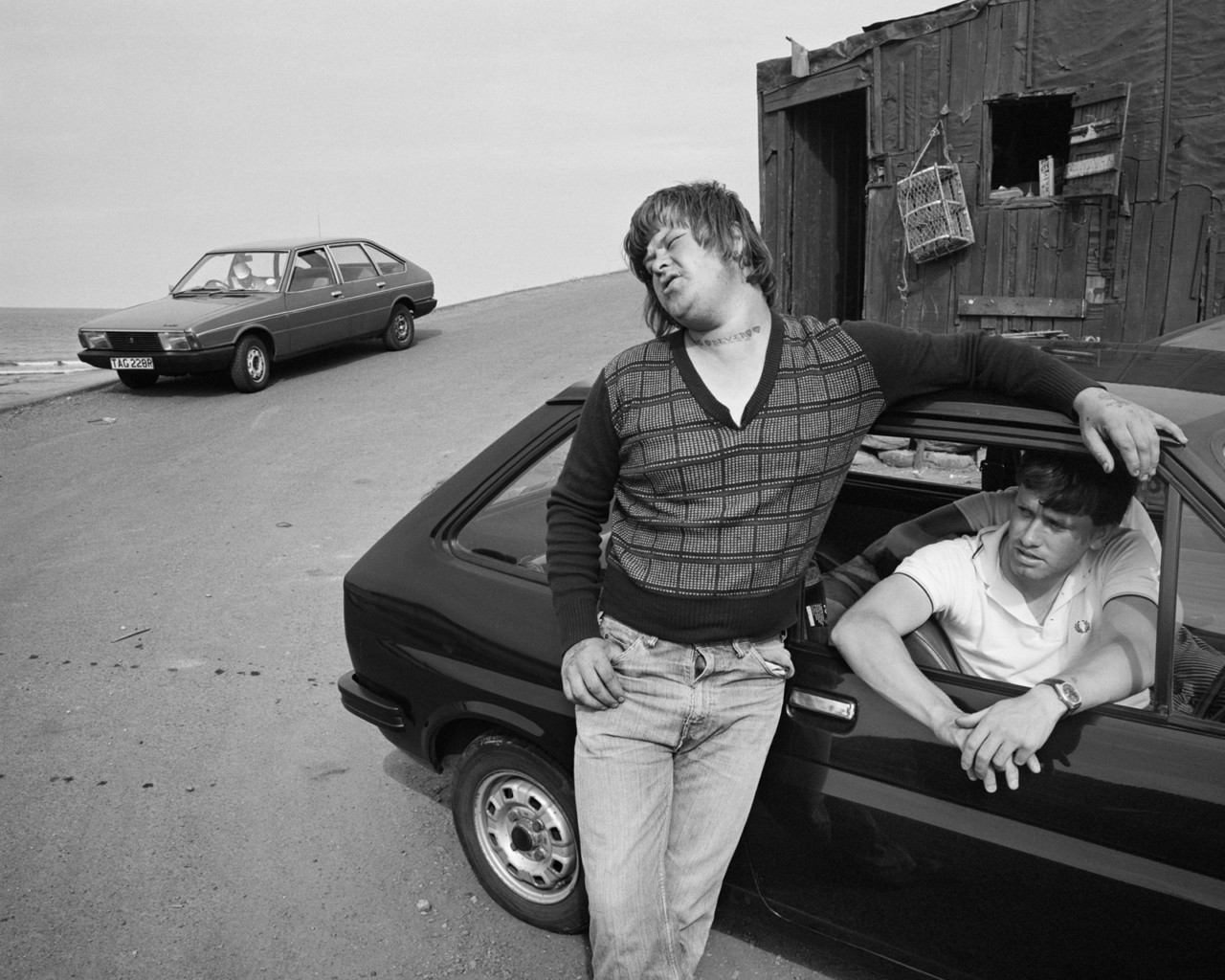

The cover of the original version of In Flagrante features the above photograph of Rocker and Rosie, for example, shot on the beach at Lynemouth. Killip spent years trying to work on this beach, a desolate stretch on which an impoverished community eked out extra cash collecting discarded coal from the sea. These people were wary of strangers but he ended up living alongside them, moving into their camp in February 1983 and staying, on and off, for the next 14 months.

He also made friends with them, forming relationships that endured through the years. Brian (below) and Rosie Laidler always wanted to feed him, even when money was tight, he wrote in a later book, Seacoal, published by Steidl in 2011, adding that their grandchildren “are now older than their children were when I took the photographs.”

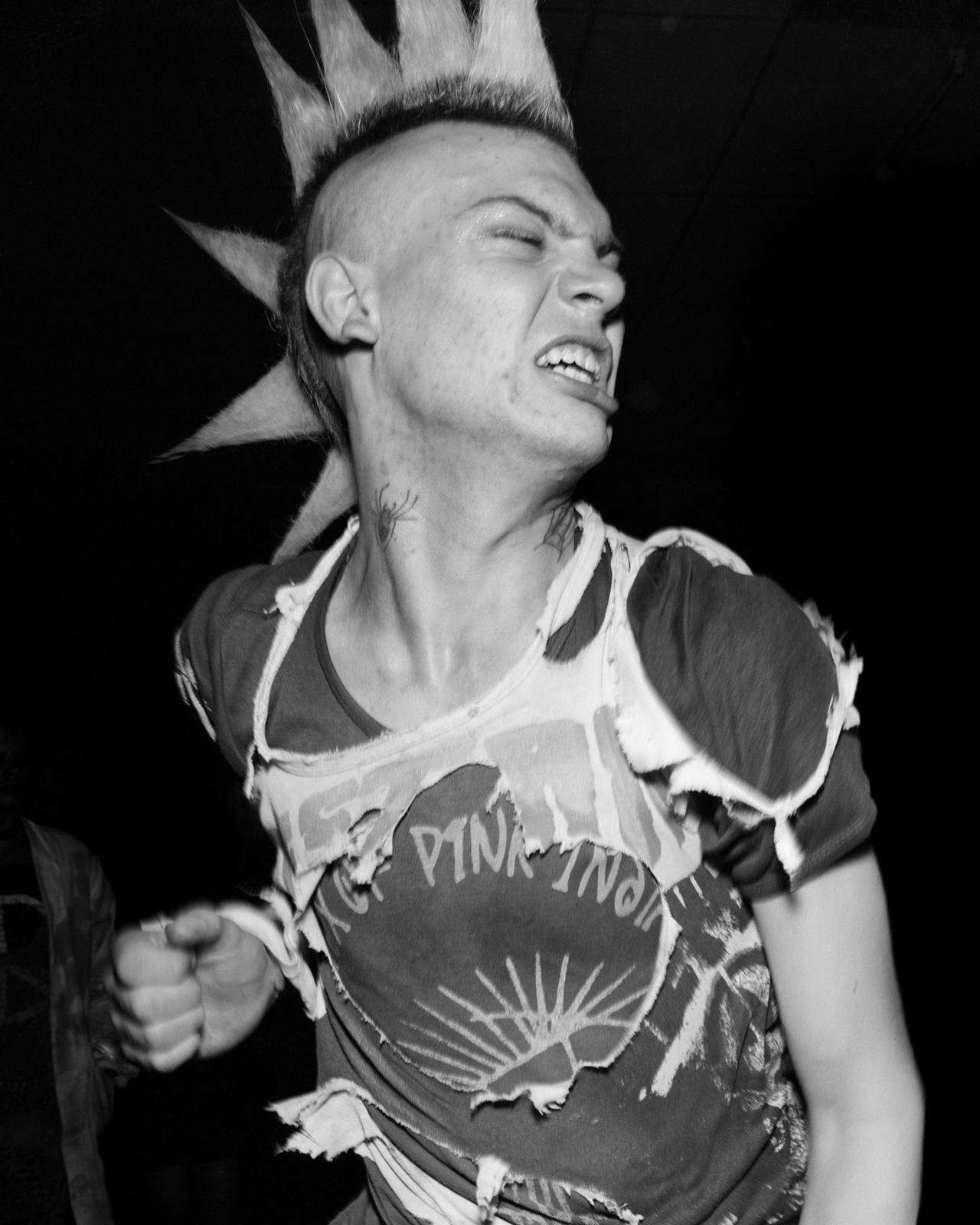

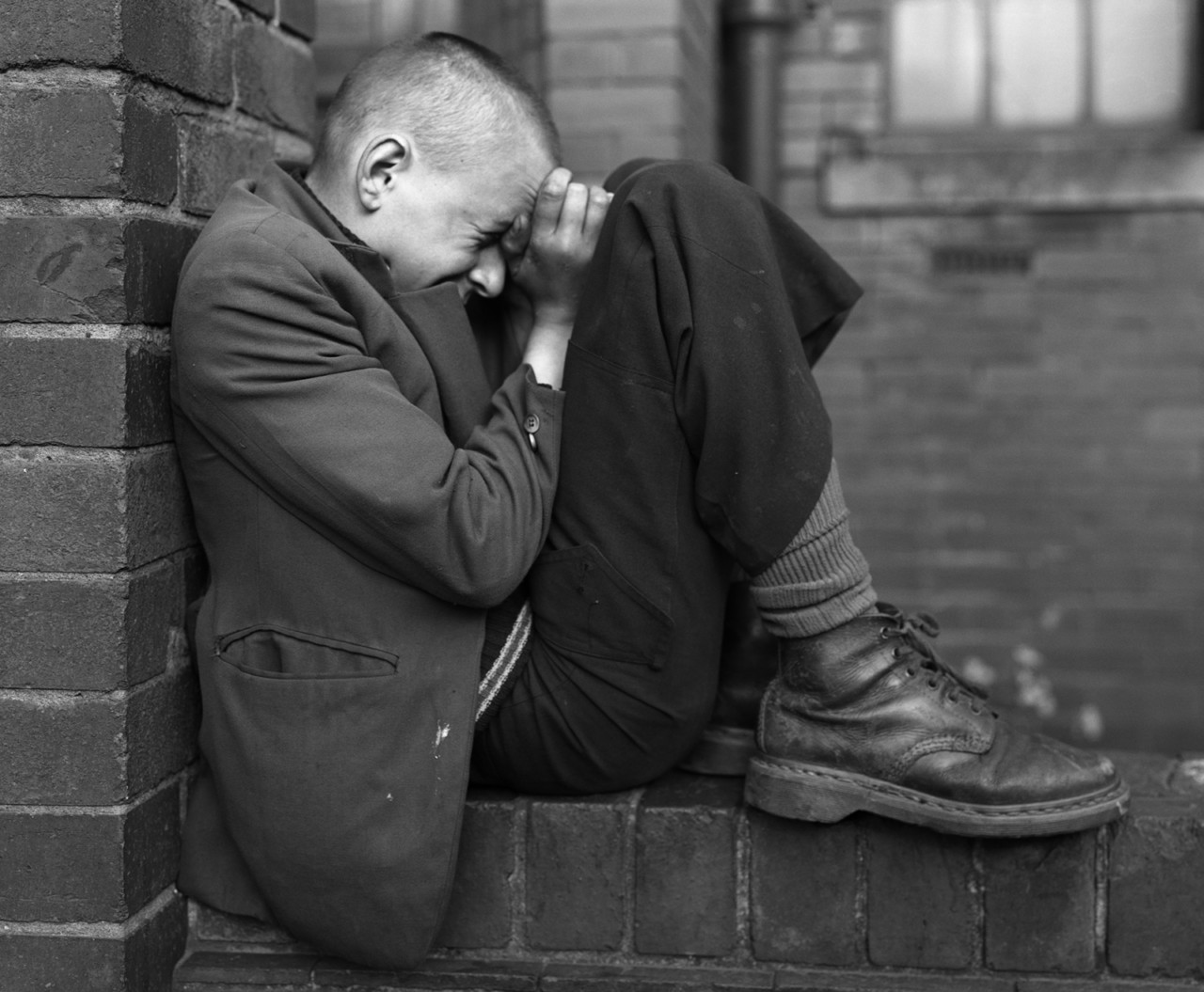

In Flagrante includes a cathartic image of young punks at a sweaty gig. Killip spent six months photographing at the Anarcho-punk, self-organised venue The Station in Gateshead in 1985. There are also three images that relate to the miner’s strike, the industrial dispute so decisive during Margaret Thatcher’s reign. Killip threw himself into covering its 51-week stretch, photographing parades, union meetings, soup kitchens, and much more.

In the new Thames & Hudson book there’s a photograph of him arm-in-arm with Arthur Scargill, then-president of the National Union of Mineworkers. Shortly before he died in 2020, Killip donated a portfolio of images from this time to the Archive of Modern Conflict. He thought it was the best place for them because they document an epic fight.

Some of the best-known photographs from In Flagrante come from the fishing village of Skinningrove, which Killip photographed from 1982 to 84. It was a close-knit community, not particularly welcoming to outsiders, yet he became a trusted member of it – so much so that, when a terrible accident killed two young men, one of the mothers asked Killip for his photographs of her boy. Killip went back to his contact sheets and made an album of three dozen shots, showing him between the ages of 13 and 17. And in 2018, when Killip made a newspaper publication of his work in Skinningrove, he anonymously put a copy through every letterbox in the village.

“When you went to his place in America, he had a beautiful display [of photographs] with all these different people on it,” says Ken Grant, a photographer who knew Killip for well over three decades, and the co-editor of the Thames & Hudson book. “There was Leso, the guy who drowned; there was [fellow-photographer] Graham Smith; I was there as a young lad from when we worked together in Ireland. He’d come in and look at that wall every morning and say hello to the people. He had a connection with them, a deep connection. Even though he was in America, those connections were absolutely current in his mind, in his thinking, in the way he treated that work.”

And those connections underpin the book and exhibition that Grant has put together with curator Tracy Marshall-Grant, his partner in life and sometimes work. Including several texts by Grant describing the arc of Killip’s life, as well as Halpern’s text and two other essays, Chris Killip takes a near-chronological look at his work, from his first book, Isle of Man (1980) to a much later body of work shot in Ireland, published as Here Comes Everybody in 2009.

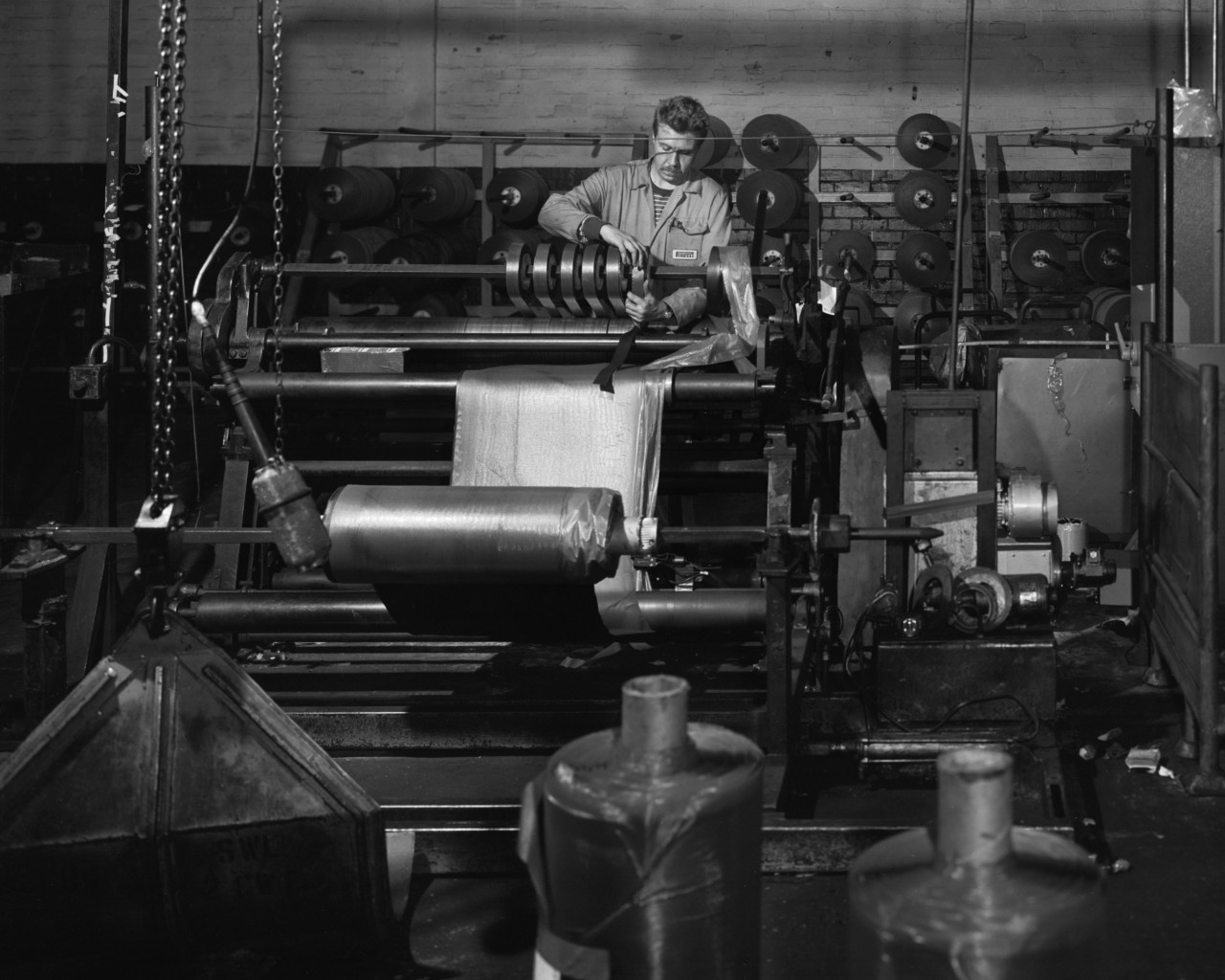

It also includes less known photographs, such as Killip’s early project on the Isle of Man’s TT Races, and his (1989-90) commission to shoot a Pirelli tyre factory in Burton-on-Trent. And though it includes many images from In Flagrante, it situates those images in a wider context, within the work Killip shot in the North East, and within his own life too.

“Some of it reflects what his work had amounted to, things that have been missing or haven’t been represented so much,” Grant explains. “But then it came down to the structure. I thought it would be very easy to say, ‘Here’s In Flagrante, here’s this series and here’s that.’ But I saw something maybe a little bit more philosophical about the idea of Chris staying connected to the places he’d made work.”

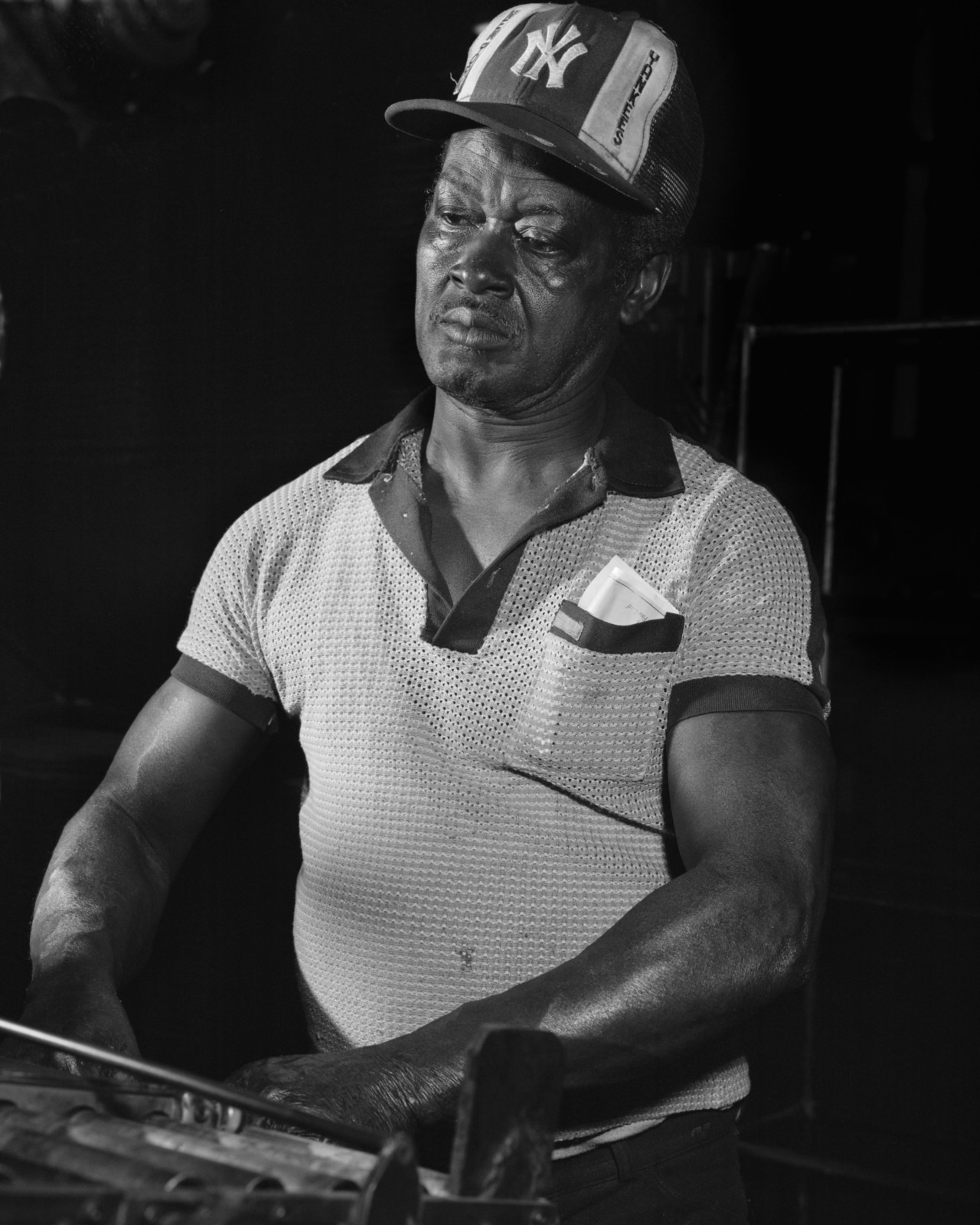

For Marshall-Grant, those connections are key to understanding Killip’s work, but also his politics, and even the man himself. Working against a backdrop of mass unemployment, in which entire communities had been written off as economically unviable, Killip insisted on the worth of each individual. Without shying away from showing deprivation, he looked beyond it to see people.

When I interviewed him back in 2017, he spoke of wanting to record people’s lives because he valued them and wanted them to be remembered, and he spoke of his work in terms of an alternative history. “History is what’s written, my pictures are what happened,” he told me. “It’s like a people’s history – the people who history happened to.”

The words echo his preface to In Flagrante, the short but palpably angry text he placed before his images. “The objective history of England doesn’t amount to much if you don’t believe in it, and I don’t,” he asserted, “and I don’t believe that anyone in these photographs does either as they face the reality of de-industrialization in a system which regards their lives as disposable.”

In Flagrante also includes a short poem by WB Yeats, which ends: “But I, being poor, have only my dreams;/I have spread my dreams under your feet;/Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.”

But if Killip hoped his photographs might help remember those written out of history, some of them lay unseen for a very long time. In our 2017 interview, he laughed ruefully that people usually asked for images just from In Flagrante, but that he had many, many more photographs from 30 years ago that he had never printed. Elsewhere, his son Matthew has said he stumbled upon Killip’s work at The Station in 2016, when he happened on a box of contact sheets in his archive. Killip was apparently taken aback he hadn’t done more with the images, once he’d seen them again.

And that’s something that comes across in the Thames & Hudson book, which, in showing more of Killip’s life and legacy, suggests there might be more to uncover. Given his commitment to those he was photographing, revisiting, reappraising, and refinding Killip’s work isn’t just a question of learning more about a great photographer. It’s an urgent political task. “There’s a much bigger set of works to explore,” says Marshall-Grant. “And a much bigger conversation to be had.”

Chris Killip runs at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, until 22 February 2023. An accompanying book, Chris Killip 1946-2020, is available to purchase here.