Aberfan: The Village That Lost a Generation

David Hurn and Ian Berry look back on their coverage of the Welsh disaster 50 years on

Magnum Photographers

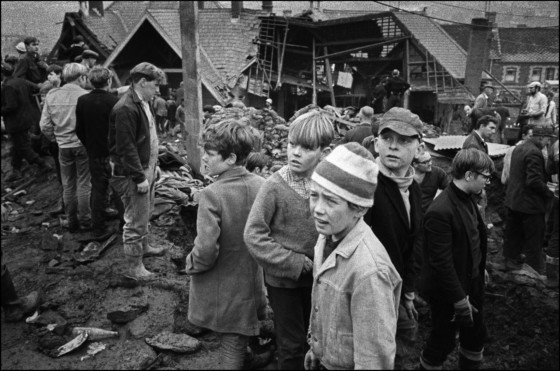

On October 21, 1966, a coal slag tip from Merthyr Vale colliery collapsed in the Welsh mining village of Aberfan, killing 116 children and 28 adults. Pupils at Pantglas Junior School were just beginning their first lessons of the day when the rushing landslide of mud and debris flooded into their classroom. The National Coal Board said abnormal rainfall had caused the coal waste to move. The Inquiry of Tribunal later found that the NCB was wholly to blame and should pay compensation for loss and personal injuries.

Magnum Photographers Ian Berry and David Hurn both travelled to the scene upon hearing of the disaster. For Hurn, who is Welsh, the event held a particular poignancy and, he says, contributed to him deciding to move back to Wales from London some four years later. When the men arrived daylight was dwindling but they found heart-wrenching scenes as miners and other villagers tore through the wreckage, pulling out only bodies by this stage.

Ian Berry recalls the events, 50 years on: “When I got there it was already dark but they were still working madly to try to clear away all the debris to get at children and bodies. By the time I got there they weren’t pulling out anybody who was still alive, they were just really recovering bodies and it was a pretty awful scene. It was a bit like after a bombing, everyone was fairly shocked, but they had sort of set-up, in that sort of Brit way, they were fairly organised, everybody was helping.”

“It was chaos everywhere. You were trying to keep out of the way because it was pretty emotional; if you were there with a camera it meant that you weren’t contributing to the rescue… It was just a case of doing what one could, climbing around in the mud. It was pretty messy and I was trying not to get in the way of people working on recovery.”

"It was just a case of doing what one could, climbing around in the mud"

- Ian Berry

For a photographer, taking pictures during an emergency situation presents a conflict between the people experiencing the disaster – “miners digging in this crap to try and get their children out,” says Hurn – who do not want a photographer around, and performing a job that may prove to have not only historical but legal significance. “Nobody can ever say it didn’t happen or that it wasn’t as bad as it was seen to be,” he adds.

Speaking in the House of Commons on Oct 26 1967, after an investigation into the disaster, Mr Arthur Pearson of Pontypridd in Wales, talked about how improper management of the site had led to a dangerous situation. Mass shale was piled up on top on the hill overlooking the school, which it eventually fell on to. He referenced images from the press of the time showing this:

“We have too lightly passed over this danger of water. Hitherto, sufficient weight has not been given to the mischief which big rainfalls can create. There have been instances during the past week, and there are photographs which show that the bases of large tips run adjacent to mountain streams which flood and wash away the sides. No attempt has been made to protect any tip by walling against erosion. Will the Minister of Power give attention to it? The photographs have appeared in newspapers for all to see these roaring streams, and no attempt has been made to wall the bases of the tips to protect them against erosion.”

"It’s a really good example of photography absolutely justifying being done"

- David Hurn

Some of Hurn’s pictures, taken when he went to see the site where the shale was heaped precariously, uphill from the school, illustrate exactly this. “It’s a really good example of photography absolutely justifying being done because of what happened afterwards, partly due to the fact that the photographs had been taken and were there. I suppose there’s a sort of parallel to George Rodger, you know, in Belsen,” says Hurn.

Following their assignment Ian Berry and David Hurn received a note from Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson, saying that their photographic coverage of the Aberfan disaster was Magnum at its best. David Hurn, who became a Magnum nominee in 1964, was made a full member in 1967, the following year.