In Rebuke of Forgetfulness

Alia Malek makes the case for remembering the history of displaced people across Europe

Magnum Photographers

Europa, an Illustrated Introduction to Europe for Migrants and Refugees, is a project initiated by a group of Magnum photographers and journalists. To mark its release, civil rights lawyer and author Alia Malek, who edited the book, explains why it is important to remember the history of displaced people on the move. Alia Malek makes the case for remembering the history of displaced people across Europe.

By now, this should all be rather familiar, we’ve been here so many times before: where there is war, displacement always follows.

Similarly, we should all know that as much as these are destructive forces, they are also integral in shaping the makeup of the many societies they touch, no matter how these countries emerge in the after – whether in triumph or defeat. And no one is really untouched. Most nations that we take for granted as cohesive today were themselves products of demographic shifts and movements, often as a result of conflict – either within their borders or from without.

Yet, once the bullet-riddled surfaces are repaired, veterans and survivors aged, refugees assimilated, prosperity regained, and other similar scars begin to fade, so does – remarkably – robust historical memory. Instead, it is what becomes pockmarked, its grooves often filled in with a collective (and at times willful) amnesia. Thus, even in places not so long ago ravaged by war and displacement, these become the afflictions of others. As such, news of them are usually greeted with a shrug, especially now that in recent decades, it is the developing world that is more often stricken.

Shortcomings of modern memory and attention spans aside, however, conflict and the waves of people inevitably spurred to flee it are nothing new, nor have they ever been only developing world maladies. In fact, the international laws that govern how nations must treat people fleeing conflict and persecution and the principles that have formed the contours of modern-day debates about refugees (including the need for collective action), all stem from a very specific European context; namely, the 20th century events that would recast the continent as we know it today, from World War I to the Spanish Civil War, World War II, the Holocaust, the expulsion of ethnic Germans, and the march of Communism.

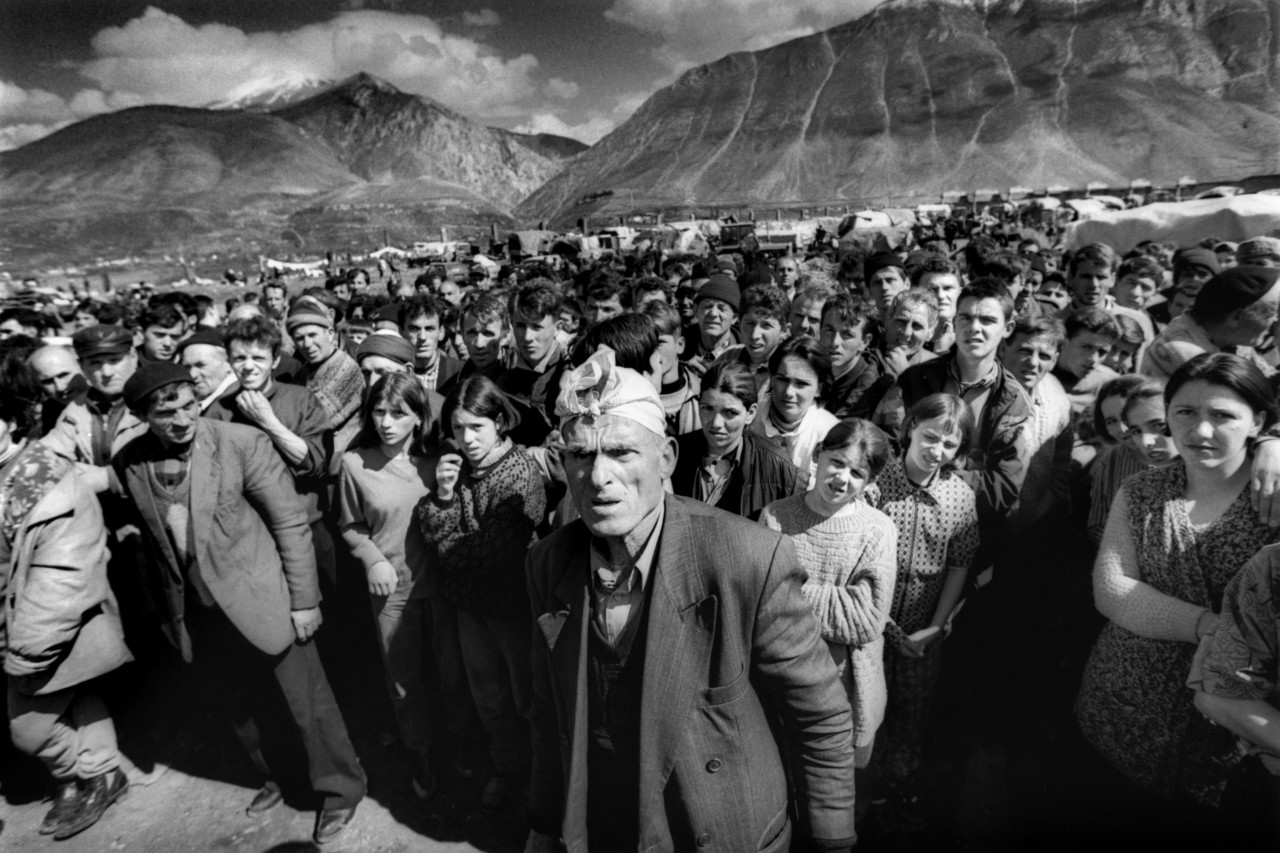

But if the events that have made (and continue to make, culture is dynamic after all) Europe have receded into distant memory because of time and because the people who lived through many of these upheavals have died, then photographs that capture these moments can serve as a powerful and tangible rebuke to our forgetfulness.

Of the images that have become iconic of these eras, many were captured by Magnum photographers. (Magnum too was established in the aftermath of World War II, itself an expression of collective action.) Already potent in their time, these pictures have become immortal witnesses to what once was and what once transpired.

These pictures compellingly capture the forcible displacement, deportation, and resettlement of millions of people in the aftermath of war — the very same events that prompted the international community to negotiate guidelines, laws, and conventions to ensure the adequate treatment of refugees and to protect their human rights. These efforts culminated in the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. While the 1951 Convention was more or less limited to protecting European refugees, with conflict and resultant displacement continuing to occur across the globe, the 1967 Protocol expanded its scope. Moreover, these laws and their underlying tenets are the foundations of important regional conventions far beyond Europe, as well as worldwide national laws relating to the treatment of refugees.

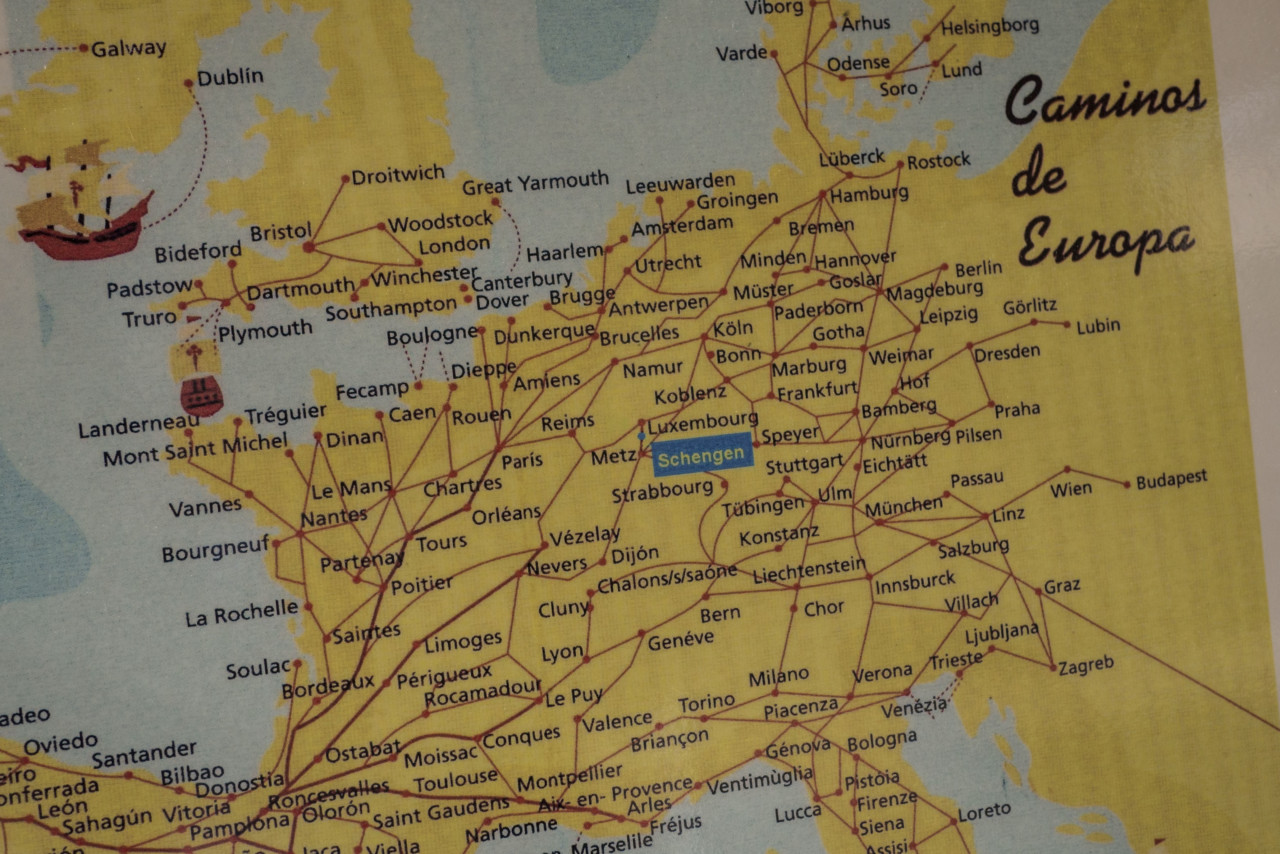

Likewise, the very creation of the European Union attests to what watershed moments these were for Europe itself. After war and displacement had devastated Europe, its countries – both former enemies and allies – began establishing a body of laws that would cement their cooperation in a number of institutions, with the aim that war would not only become unthinkable, but materially impossible. In addition to integrating their trade, creating a common currency, and opening their borders, they also developed a common asylum system in keeping with the 1951 Convention. This system has been used as Europe has dealt with non-European asylum seekers as well as new waves of European refugees caused by the fall of the Soviet Union and the disintegration of Yugoslavia, which in turn have continued to shape Europe as we know it today.

However, the current state of the debate around refugees in Europe – as the continent faces a large, but by no means its largest, movement of refugees – would imply that many Europeans believe that Europe itself has never seen conflict or migration, as if it had emerged like Venus from the sea, intact and unchanging. This has helped fuel a kind of hysteria that posits that what is happening now in terms of the refugees in Europe is so unique that EU member states must suspend their cooperation in collective decision-making and abandon the values they supposedly embraced in joining the union in the first place – values for which the EU was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012. (Never mind that the developing world bears exponentially more of the planet’s refugee burden, displacements that external meddling, both past and present, can claim partial credit for.)

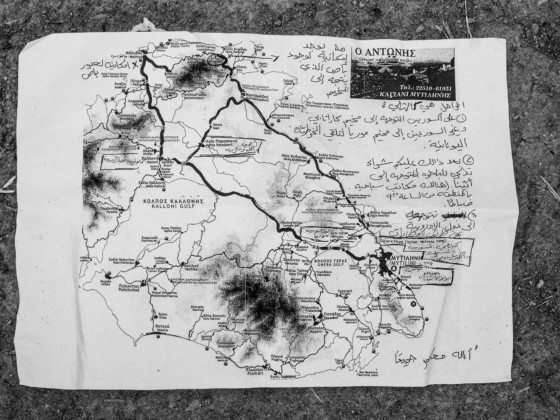

It was while photographing this mass movement of people into Europe that Magnum member and photographer Thomas Dworzak conceived of Europa: An Illustrated Guide to Europe for Migrants and Refugees, a book on which both Magnum Photos and the Magnum Foundation collaborated. After frequently being asked for information by refugees as they travelled to Europe, he saw a need that he thought photography and Magnum’s impressive photographic archive could help answer. The project soon grew to include a team of photographers and journalists who have been covering both the refugee crisis in Europe and the many contexts across the Middle East, Asia, and Africa that gave rise to these migrations.

I was brought on to develop the content and structure that would be built around the photographs. To do so, I was guided by conversations I had had in Syria as it unraveled and in Europe as I journeyed with thousands of people making their way from Greece to Germany in the summer of 2015. Certain things I heard repeatedly struck me. Many Syrians and Iraqis told me that the kind of devastation, societal disintegration into civil war, and displacement they had experienced had not been seen in recent human history. Yet we had these very conversations on Greek islands where elderly inhabitants had once been cast out and made refugees by the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and as we trekked through the Balkans, navigating borders still mined from the not so long before days of the Yugoslav war. They spoke of this as they desperately journeyed to an EU that was created because of war and as we crossed borders already well traversed for decades by other refugees. They shared with me their shame of having come from places that had been destroyed for refuge in places that were instead flourishing – as if the place they most wanted to reach, Germany, had always been as it is today.

So many were unaware or had also forgotten this relatable history of a past that arguably resembles the present in the countries they had fled. This is why for Europa we selected war and displacement as the lenses through which we would introduce contemporary Europe to these newcomers. Knowing Europeans might also come to the book out of curiosity, we thought we might also remind them of their own past.

To help tell this tailored visual narrative of Europe, in addition to photographs and explanatory text, the book also features first person oral histories. Readers and viewers are introduced to the many different people who make up Europe today, from citizens to residents to immigrants to old and new refugees – in their own words telling stories of displacement, war, solidarity, and even reconciliation. Our idea was that in a shared experience, refugees and Europeans might see themselves in the other.

And many of those whose testimonies we share do see much that is familiar in what is happening today – listen to two of them in their own words, speaking about conflicts that bookend Europe’s 20th century.

“In Spain there are at least 114,226 missing people in mass graves. Thousands also went missing into exile and died there, unable to return. Almost half a million Spanish men, women, and children crossed the border on foot at the beginning of 1939, looking for refuge in France, fleeing the fascist armies of Franco, Adolf Hitler, and Benito Mussolini, who had allied themselves in the war in Spain. Many of the Spanish refugees were transferred to internment camps built by French authorities on the beaches, where women gave birth in the sand, the conditions were miserable, and many people fell ill. The image of desperate, hungry people behind wire is something that has repeated itself throughout the world since our time. It’s the same fear, the same desperation, and the same lack of government solidarity.” – Emilio Silva, Madrid, president, Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory in Spain.

“Many Syrian cities look like Bosnian cities, and the sort of mode of destruction is similar. When I see pictures of Aleppo, it’s so spookily similar to pictures from Sarajevo during the war, and that is soul destroying in the sense that when you go through something so tragic, with such a huge loss, you hope that — at least I try to make sense of it by believing that OK, maybe we’ve learned something from this and, now we, as a human race, won’t make the same mistakes again. But, sadly, we do. War is a very high price for those who experience it, but the rest of the world is not very good at learning from others’ mistakes.” – Zrinka Bralo, London, CEO Migrants Organize.

Of course, even if there is something familiar in different conflicts and displacements, they each also have their own specificity. And we can’t ignore the changes time and technological advancements have wrought. Today for example, thanks to social media, states no longer have a monopoly on the narrative of what is happening inside their borders, images and words can be disseminated much faster and without filters, and people across the world can build relationships without ever meeting. There are more opportunities for individuals to act independently in reaction to developments facing their societies. There are also challenges, such as the impact of climate change on people’s ability to survive, which newly try longstanding definitions of who is a refugee.

And in Europe today, there is much made of how these refugees are particularly different from the refugees of yesteryear, which will make them particularly difficult to successfully integrate.

Yet these arguments have been made before, with difference once easily constructed where today we might see none. In Europa, for example, readers can meet Ira, an ethnically German woman from Latvia who fled the USSR, because of religious persecution (she’s a practicing Christian). She made it to West Germany in 1977 when she was 14. She recounts how there, her classmates bullied her because they found her way of dress and grooming too foreign (no, she didn’t wear a hijab) and how teachers discriminated against her because of her language skills (she spoke German). Today she is a docent at the museum opened at the refugee camp where she was once processed and where new refugees continue to arrive.

Indeed, none of the influxes of new people to any place have ever been without their growing pains. They are an inherent part of the process of becoming a part of each other – even in the societies that we today take for granted as being whole. It would likely be energy better spent to expect it and plan for it, rather than aggravate it with xenophobic rhetoric and policy. And given that we have yet to rid ourselves of war and its consequences, it’s a process that is destined to be repeated. If we want to instead quicken our learning curve each time these events occur and draw on similar experiences – both the successes and the failures – then we need to know of them in the first place. That means documenting them, as Magnum photographers and other storytellers continue to do across the globe. And we’ll likely need to hold on to these testimonies for future generations, when we again forget and need reminding.

Europa: An Illustrated Introduction to Europe for Migrants and Refugees is a book created by a group of Magnum photographers and journalists who have been covering both the refugee crisis in Europe and the many contexts across the Middle East, Asia, and Africa that gave rise to these migrations. This book is launched in partnership with the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) as the first project under its special program, the Arab European Creative Platform. The book harnesses the collective energy, skills and resources of its contributors to create Europa, a collaborative and independent book, the first of its kind intended for practical use by migrants and refugees, and as an educational tool to inform, engage, and facilitate community exchange.

Written in four languages – Arabic, Farsi, English, and French – the book offers an introduction to the motivations behind the creation of the European Union, how it developed, its current ethos, and the relevant debates that will determine its future. Through first-person testimonies, readers are also introduced to many of the different people who make up Europe today — from citizens to residents to immigrants to old and new refugees — who in their own words tell their stories of displacement, war, solidarity, and reconciliation.

In the spirit of a travel guide the book also offers “Practical Information”. This chapter highlights the major destination countries, providing basic information about the different political systems, geography, demographics, traditions, as well as typical foods and drinks, films and books of interest, and a list of institutions and organisations that provide information and service to migrants and refugees.

Europa has been produced in partnership with the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) in the framework of the Beirut-Berlin Creative Platform (BBCP), Magnum Photos, Al-liquindoi, and On The Move, in cooperation with Allianz Kulturstiftung, Magnum Foundation, and the Geneviève McMillan-Reba Stewart Foundation.

To view and download the eBook in English, click here.

To view and download the eBook in Arabic, click here.

To view and download the eBook in Farsi, click here.

To view and download the eBook in French, click here.

Please note: The eBook is formatted to open in iBooks on iOS for Apple users or in Google Play Books for Android users. You may need to download the associated software.

To view and download a PDF of the book in all four languages, click here.

Additional print runs can be ordered by qualifying organizations through Al-Liquindoi: email Jessica at jessica@al-liquindoi.com for more information.