Embedding in Iraq

Fifteen years after the Iraq War began, Magnum photographers reflect upon the role of embedding with the U.S. military and how it affected the work produced during the conflict

Magnum Photographers

At the start of the Iraq War, many photographers faced the same decision: whether to attempt to go independently, or to go embedded with U.S. or British forces. Embedding, the practice of journalists linking up with military units so that they can report from the frontlines, began formally with the invasion of Iraq. More than 700 journalists embedded with American forces and another 100 with British forces after agreeing to the terms of US Public Affairs Guidance or the U.K.’s Ministry of Defence.

Embedding was, in part, a response to pressure from American media, angered by the limited access they obtained during the Gulf War in 1991 and the invasion of Afghanistan a decade later. The military also felt embedding journalists helped achieve a larger goal. Lt. Col. Rick Long of the U.S. Marine Corps said their job was to win the war and “part of that is information warfare. So we are going to attempt to dominate the information environment.”

Logistically, being embedded was often the only way for journalists to cover some frontline locations. At the same time, it meant combat units occupied a central role in the narrative; some critics have argued much of the photography of this period made the Iraq War seem like a video game with triumphant action figures fighting in a desert. Embedding also meant the local community often went largely unseen, apart from in encounters with the military.

For many photographers, embedding also threw up ethical questions: a photographer or journalist would be inherently dependent on them for safety. In Iraq, that also meant relying on them for weeks for food and water in the middle of the desert. To this day, debates continue as to how much the events of these wars were therefore filtered through the perspective of the American military and its allies.

As part of a series for the 15th anniversary of the Iraq War, Magnum is sharing reflections from its photographers on that momentous conflict. Here, we speak to Paolo Pellegrin, Alex Majoli, Christopher Anderson, Moises Saman, Jerome Sessini and Thomas Dworzak about the dangers of working in Iraq and how working alongside combat units influenced the work that emerged out of the war.

Access, safety and objectivity

While the practice of embedding with military units was common in Kuwait in 1991 and in Afghanistan in 2001, it took off more in Iraq—in part because of how dangerous the war became. The sectarian insurgency of 2006-2007 transformed the way journalists could work, making them largely dependent on the military units with which they were embedded.

But even before that, Iraq had been a stark contrast to earlier wars, where photographers and reporters were considered neutral and able to work with little interference. In Vietnam, for example, journalists and photographers could operate with relative freedom on the ground—even if publications selected what work to publish to support their narrative. That changed in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“After September 11, you were no longer an observer; you were a target by one side,” says Christopher Anderson. “In other conflicts I had covered up to that point, like Bosnia, you had more of an ability to move around because you were seen as a necessary tool by all sides in having their story told. In Iraq, you didn’t serve a function to the other side; the insurgents in particular had their own way of getting their message out.”

"You only see that very narrow part of the story. It’s valid but it doesn’t really speak to the experience of Iraqis or many other people involved. "

- Moises Saman

Photographers like Paolo Pellegrin and Alex Majoli did not embed with combat units in 2003—but nor did they spend much time in Iraq after the initial invasion (though Pellegrin returned more recently for projects in the last few years). “I chose to go unembedded because I didn’t want to see the events that I was going to be exposed to through the filter of an invading army, essentially,” Pellegrin says.

Pellegrin acknowledges that while he had made the decision to be “as equidistant as possible,” there was nevertheless a real issue of access. “Maybe 15 years ago, I was more romantic or naïve. Now I think, for the most part, you can still maintain your independence and point of view and even if part of the work is done in embeds, it has a place in a larger body of work.”

What embedding means

Others question whether embedding in Iraq alongside coalition forces was particularly different from other conflicts, noting that the term could be applied in retrospect to other wars—though official documentation may not have been needed. “When covering conflict, you are often ’embedded’ with one side or the other” says Anderson.

Majoli agrees, saying that while the embeds in Iraq involved official documents, for him “you’re always embedded in one way or another—whether you’re with the Serbs or Bosnians or Croats; with the Russians or the Chechens; with either side of the Rwandans fighting.” The difference in Iraq, however, was that foreign photographers could only take one side—that of the Americans. The Iraqi side saw them as the enemy.

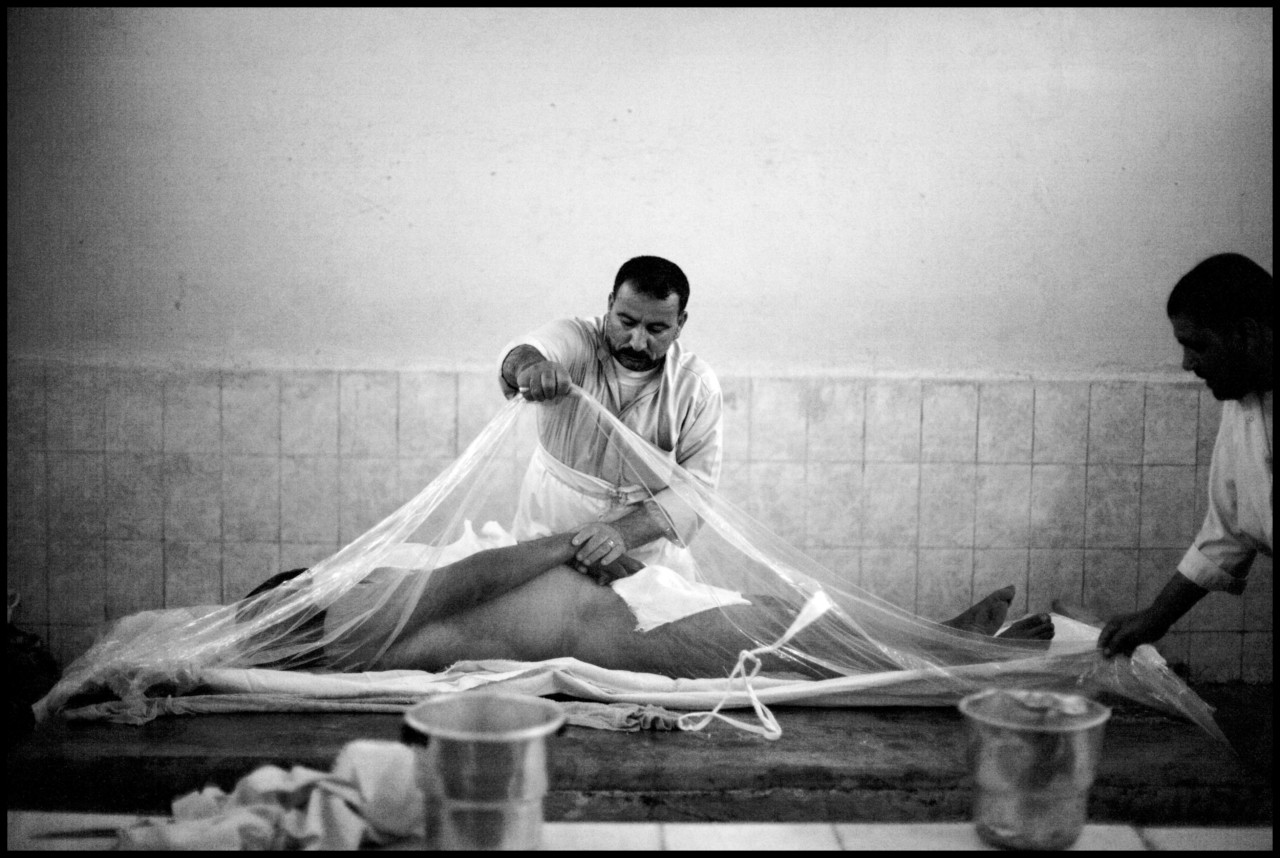

Majoli, who only returned once after initially covering the invasion, recalls why he never wanted to go back to Iraq. “It’s not my way of working—I don’t work with soldiers, military or bodyguards; it’s impossible for me. I have to feel part of the discussion, I need to taste the food and talk with the people and go to bars. I am really not interested in just being there to file pictures.”

Other photographers felt that with kidnapping being a very real possibility, embedding was the only option to work in Iraq. “You think you can control the danger,” says Thomas Dworzak. “People don’t think they can be killed on embeds and that’s what made the difference.”

“I was always defending embeds in a strange way,” he adds. “Not because we learned anything about Iraq — because I know nothing. But I thought the embed was a good way to cover that conflict and be on one side. I managed to show injured people, dying people, I photographed an American soldier dying. I felt I could do my job.”

Dworzak says an additional benefit of the embeds was the sheer lack of decision-making or production involved; rather than spending hours trying to find a driver and fixer and setting up logistics, he could simply focus on photography. He argues that the embeds broke down the separation between experienced “war photographers” and others. For the first time covering wars became accessible to a wide array of journalists, especially those from the US who could embed with their hometown units (though very few actually did), and not just reporters seeking out war and conflict. It became the norm to cover war, an expected part of a journalistic career.

Too close to their subjects?

For Peter van Agtmael, there was no real possibility of working in Iraq unembedded. He first went in January 2006, at the age of 24—when the sectarian insurgency was taking off. Until going to Iraq, van Agtmael’s idea of photojournalism was one in which “you go to an exotic place, where people whose language you don’t speak are having the worst day of their lives and you take a photo of it.”

But he found it difficult to fall into that role. In Iraq, however, things felt more natural because he was embedding with US soldiers who were around his age. “I was connected to this as a young American man. I was with my people, my generation, in these circumstances that I understood. It was a powerful feeling, to feel that I was in the right place for me at that time.”

Moises Saman points out that “it’s easy to jump on the bandwagon of criticizing the military but they were super young, often not well-trained. They were just kids in this situation.” But for him and others, while the benefits of embeds were clear, they still had to grapple with the ethical questions of working so closely with the military and feeling part of that team.

“Your proximity to your subjects naturally influences the way you see things,” says Anderson. “I spent a lot of time with the particular soldiers I was with during the invasion and lived through some pretty traumatic things with this group of young men. I wounded up having a certain filter by which I viewed them. It’s human.”

Saman agrees that the embeds created a way of working where you become particularly close to one group of people. “You only see that very narrow part of the story. It’s valid but it doesn’t really speak to the experience of Iraqis or many other people involved,” he says. Often the only way to visit a certain area was with the military. Nevertheless, Saman says he tried to work independently as much as possible. “For me what always interested me was telling the story from the ground, to look at the experience of Iraqis. That also came with a whole set of challenges that I had to face, the main and obvious one that I was not Iraqi myself and don’t really speak the language.”

Dworzak recognizes the limitations of the embeds and how he perceived Iraq during his time there. “I have to face up to it. Iraq never really grew on me the way other places did. My memories are almost purely American,” he says. “I don’t think I would know my way around Baghdad but I would know my way around the bases. But I was there to document the American occupation and from that point of view, I’m happy with what I did and how I did it.”

Censorship and embedding

During the Iraq War, several commentators spoke about the censorship of images. In 2008, a freelance photographer in Iraq was barred from covering the Marines after he posted photos online of several of them dead. Some journalists at the time said the American military increasingly began to control graphic images from the war in an attempt to stem public opposition to the war.

None of the Magnum photographers say that was their experience. “I was convinced that everything would be super controlled, but in fact it was easy to work with the Marines. You have a few days to adapt, to make them welcome you in the group and from there it becomes very easy to photograph everything,” says Jerome Sessini, who embedded a few times from 2004 to 2006 in Fallujah, Mosul and Baghdad. “In Fallujah, I photographed soldiers throwing bodies from the rooftops. I thought they were going to throw me out of the embed but they were fine. One guy was actually proud of it.”

Van Agtmael agrees, saying his experience of the embeds wasn’t one in which he felt censored. “It depends when you were in Iraq and what unit you were with. I was generally accepted because I was a young man, and I was a photographer rather than a writer—and many of the soldiers were concerned about having their words twisted. I had very few restrictions put on me. I was never censored from photographing people who were killed or hurt or angry or weeping.”

At the same time, while individual photographers felt they were able to operate with freedom within the system of embedding, they did not necessarily have control over how publications used their pictures in reinforcing the official war narrative.

Looking back, van Agtmael sees that feeling as the product of certain circumstances and his age. “It was easy to see it as an American war then. But after a few years of looking at things from the American perspective in Iraq and Afghanistan, I felt it would be unfair to say America was at the center of it, because of the impact on civilians in the countries we had invaded. So much of the attention was focused on the Americans and yet in human terms, they played a small part.”

From that perspective, the embeds shaped the photographers’ understanding of Iraq, providing a certain frame for their visual representations of the conflict — even as they captured the raw realities of warfare. “It changes people’s demeanors and limits opportunities for real intimacy,” says van Agtmael, who noted that his superficial impression of the Iraqis as unfriendly had more to do with being with the military.

Once van Agtmael saw what he was missing, he shifted gears, deprioritizing the American angle. From 2006 until 2010, van Agtmael’s work focused on the American soldiers and the impact back home, but since 2014, he has dealt more with the other side of the war—the civilian population and the Iraqis in exile. “In America we tend to see them as anonymous victims rather than these fully-formed lives. The goal of photography is to create a more complex picture.”

While embedding made visible aspects of the Iraq War that would otherwise have remained hidden, it no doubt centered the American perspective and sometimes narrowed the range of visual subjects. In the next chapter of our series on Iraq, we will be speaking to Moises Saman and Peter van Agtmael about how their later work sought to shift away from that perspective.