Chechnya: Images of a Forgotten War

Thomas Dworzak's coverage of the First Chechen War, 25 Years On

A quarter of a century ago, ill-prepared and ill-equipped Russian troops were sent into Chechnya, a breakaway republic whose leadership had in 1991 recently declared itself free from Moscow’s influence. Magnum photographer Thomas Dworzak had been working in the country for some time before hostilities commenced, and his images of the war reflect his connection to the place and its people. Lawrence Sheets, Moscow Bureau Chief covering the Caucasus region for National Public Radio (NPR), was with Dworzak during the bloody, and under-scrutinized conflict. Here, Sheets reflects upon the war, Dworzak’s images, and the legacy of Russia’s campaign.

Warning: The following feature includes images which readers may find disturbing

Thomas Dworzak was all of 19 years old when he first showed up in Chechnya. It was June 1993, well before the first Chechen War began. Those of us who were there at that time were a tiny lot. Thomas told his father he was coming home, to Bavaria, in two months. In actuality he remained working in the region for 20 years.

The images presented here are the most empathetic made during that first, senseless Chechen war. Thomas was by far the most hard-working of us. He operated on a shoestring budget. While we waited for drivers and escorts, Thomas was usually awake by 5am and gone, departed on smoke-belching old Ukrainian buses.

There were plenty of photographers coming in and out of Chechnya by the time the war had started. In 1994-95 alone 19 journalists died or disappeared, in a territory about the size of Rhode Island or Luxembourg.

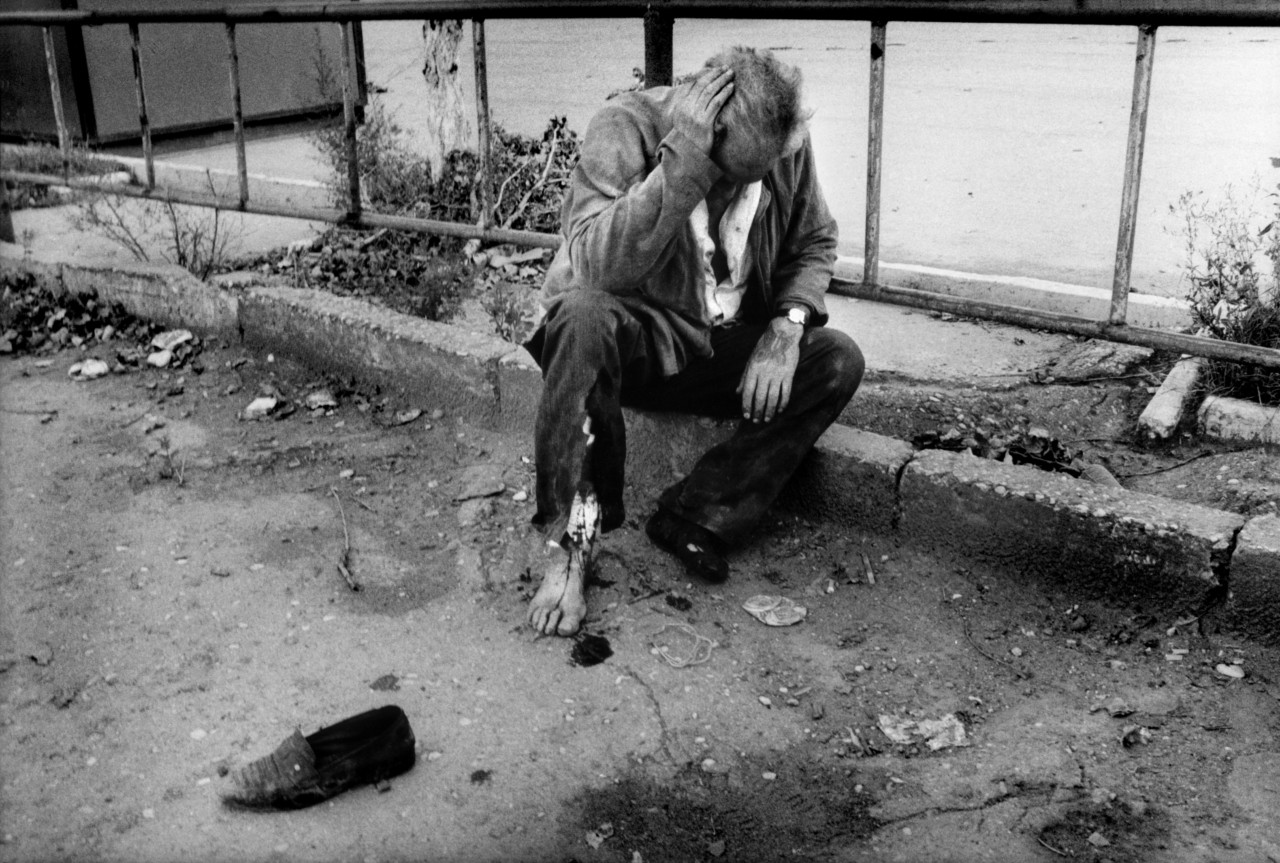

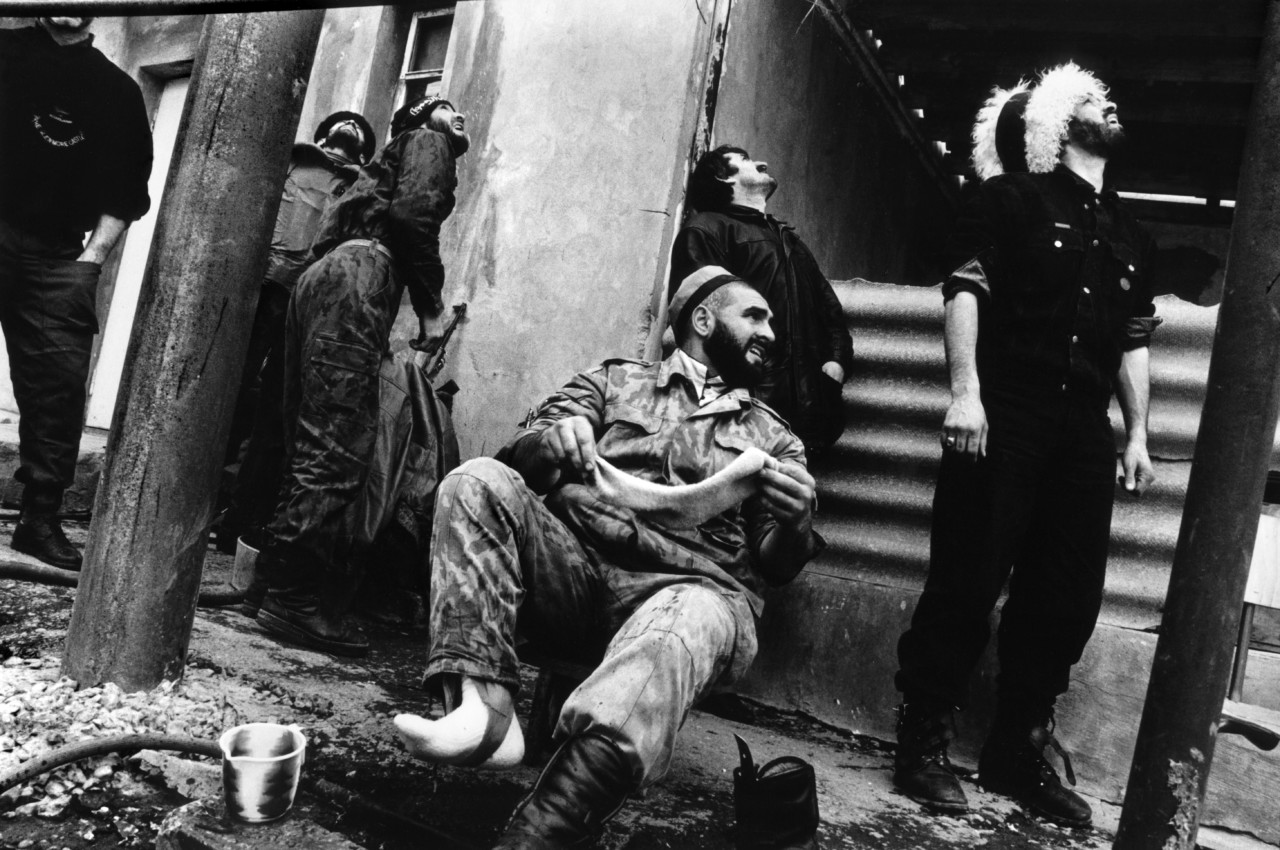

The images you see here are the best of that horrible time. They are not accusatory or politicized. Many were taken over a year before the war began. They reflect the realities of life in Chechnya at the time. Chaos. Disorder. Contradictions. Normalcy and anarchy. Solitude and bedlam. Bullet strewn walls. Russian conscripts totally unaware of the hell they had descended into, often begging for cigarettes or abandoning the battlefield. It is all here. The images demonstrate subtlety, power, and an unmatchable range in Dworzak’s work.

The most surprising – and tragic – thing was that the war took place at all. During the unbridled assault that came, a greater tonnage of bombs was dropped on the regional capital, Grozny, than was on Dresden during World War II. Three years of indiscriminate use of force of every type, left most of the city of 400,000 a smoking ruin, and, by the time the conflict was over – in 1997 – there were at least 50,000 casualties, mostly among civilians, but also among the Russian soldiers ill-equipped for combat and left traumatized. The war also created hundreds of thousands of Chechen refugees, bombed of their homes.

What at the time seemed equally unbelievable was that the Chechens were prepared to fight at all. Almost all journalists had scoffed at the notion in the lead-up to the war. After all, Chechnya, with a population of around 1 million, would be taking on Russia – population 150 million. Chechnya had no real army, just mostly volunteers with AK-47s, a few pieces of old military hardware, no air force, no real air defense system. Never truly independent, Chechens were nonetheless scarred by their mass deportation in 1944 when the entire population was sent in cattle cars to Central Asia, only to be allowed to return in the 1950s after the death of dictator Joseph Stalin.

The exact date of the commencement of hostilities is hard to pinpoint. Russia began moving regular troops into the region in December, 1994, but in reality had been using Kremlin-backed local Chechen proxy militias – mostly from the more pro-Moscow north of the republic – from much earlier. All of these proxy groups failed in every attempt to topple nominal president Jokhar Dudayev, a former Soviet Nuclear Squadron commander who returned to Chechnya in 1990, even though he was highly unpopular and likely would have been deposed by his own people, given the chaos in the tiny republic. The real large-scale battles did not commence until January of 1995, a quarter century ago, and Russia never gained full control of much of the territory, especially in mountain regions.

The prelude to all of this had begun with a unilateral, non-recognized declaration of independence by pro-Dudayev forces in Chechnya. At the time few international journalists had even heard of the place, nor was there much interest in it, given the larger meltdown of the USSR that was at hand, and the obscurity of tiny Chechnya.

But Thomas was there, in the middle of 1993, almost 2 years before “official” hostilities began, one of only a very few journalists who expressed interest. It gave him a unique perspective on what was unfolding and what would evolve into that savage, if somewhat forgotten, war.

Many of the photos emphasize themes which most pundits missed. For instance, Grozny, first established as a forward line during the Tsarist conquest of the area in the 19th century, was home to a very large number of ethnic Russians. Chechens often had extended families to stay with outside the city, but the Russians were relatively recent arrivals and had no place to hide the constant bombardments. They suffered as much as anyone else.

The “end” of the formal war came in 1997 when the Russians conceded defeat. Unfortunately, Grozny, which had formerly been a largely secular place with a large, broadly moderate sufi-based population was transformed during the horrors of the war into a cause for radical sects of Islam to infiltrate. The republic, still unrecognized, was a hotbed of kidnappings for ransom, radicalization, public firing squads, and became complete no-go area for most. In late 1999, the Russian army returned, this time not making the mistake of sending untrained conscripts to the area. Instead, they pummeled the place for weeks on end with airstrikes, artillery bombardments, and the like until there was even less left than after the first war. Finally, all real resistance receded.

Chechnya today is “formally” a part of Russia, and receives more than 80% percent of its budget from Moscow. Yet local Chechen laws fly in the face of Russian legislation, a discrepancy seemingly ignored by Moscow for reasons of expediency and head-scratching about what to do next. Instead of discouraging terrorism, Russia stoked it mightily.