The Silence: 25 Years Since the Rwandan Genocide

Author Philip Gourevitch’s memories and Gilles Peress' images: the importance of documenting atrocity

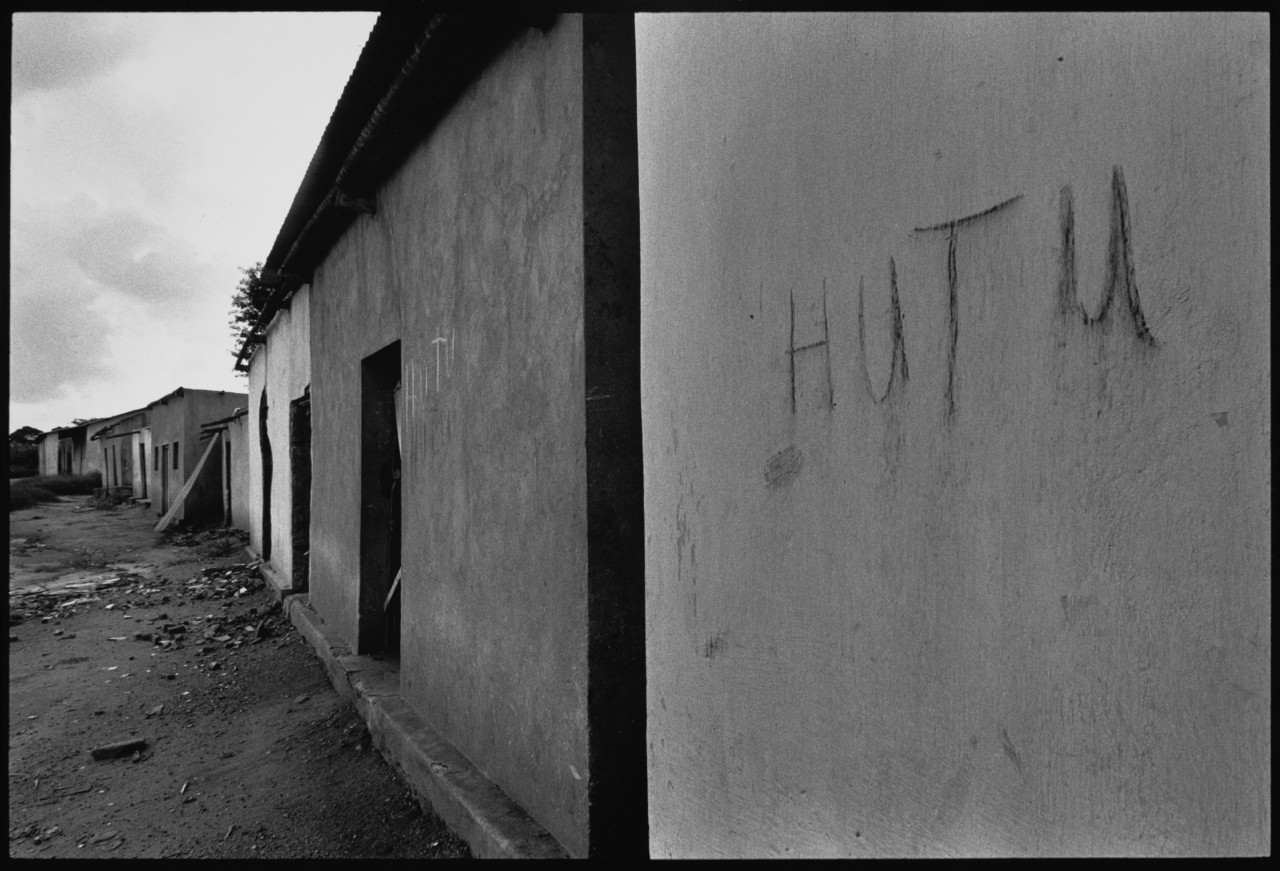

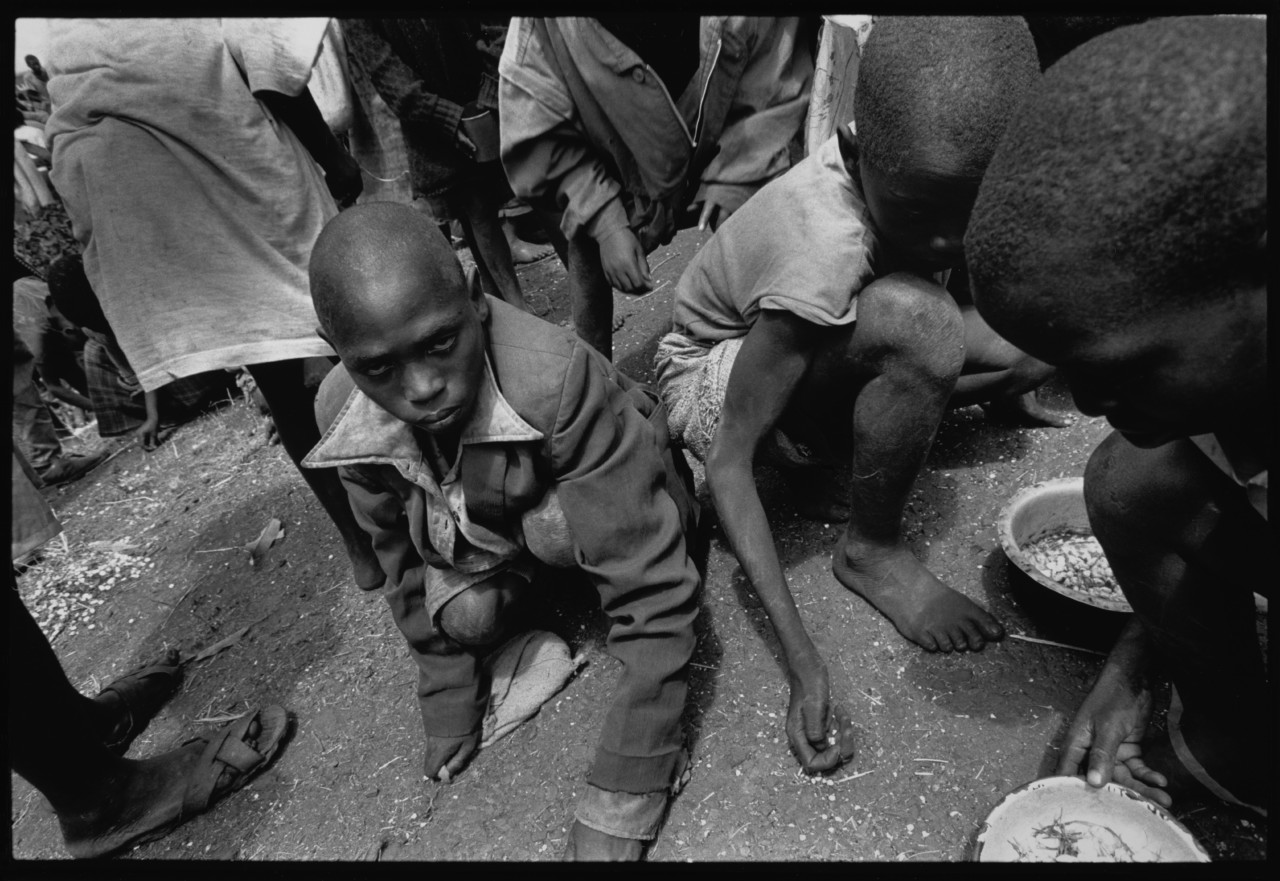

On April 6th, 1994, the Rwandan genocide started when the country’s Hutu-led government issued orders for the killing of the Tutsi minority. In around 100 days nearly one million people were killed. The country’s population was decimated – in a literal sense – around one in ten of its people were left dead. Most of the killing was done by hand, with machetes or clubs, and often the killers and victims were known to each other.

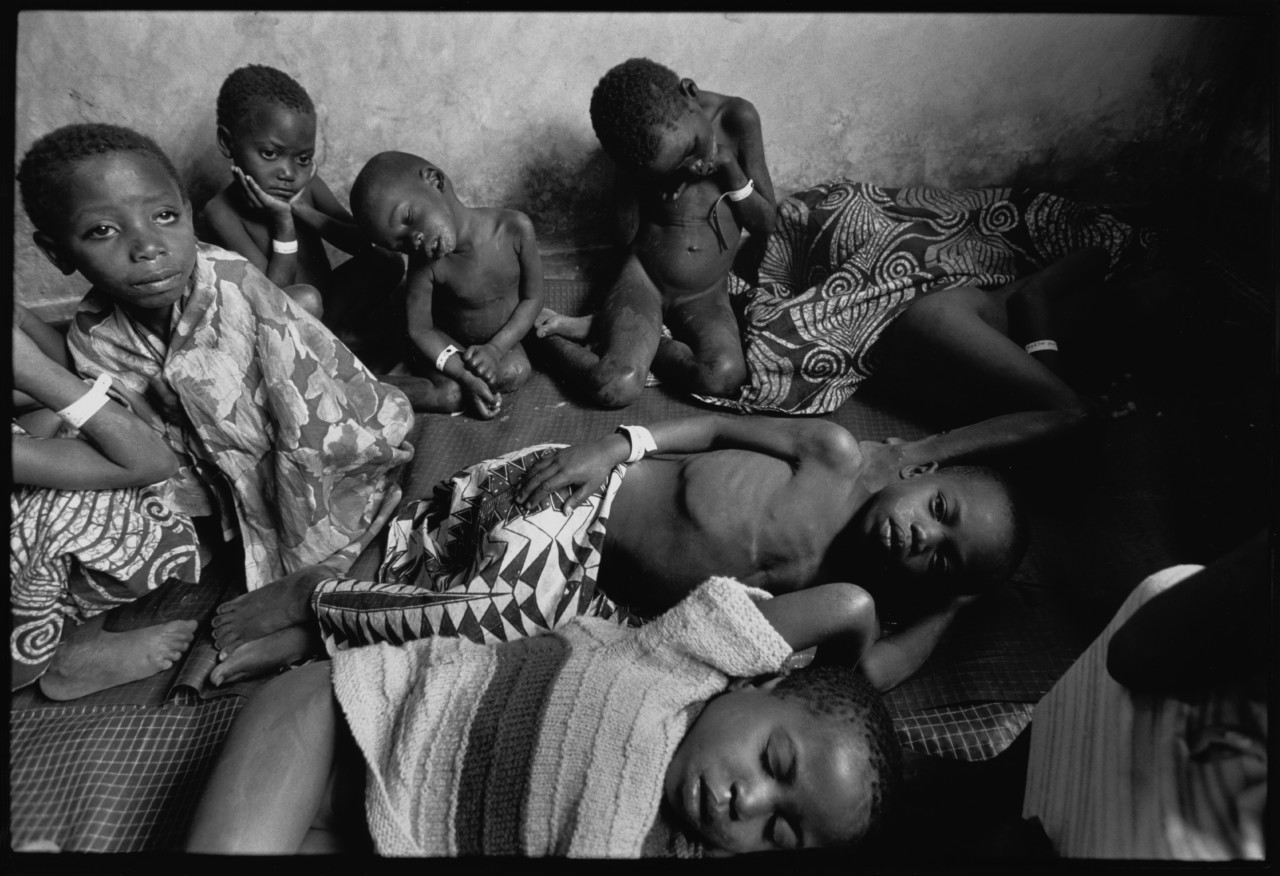

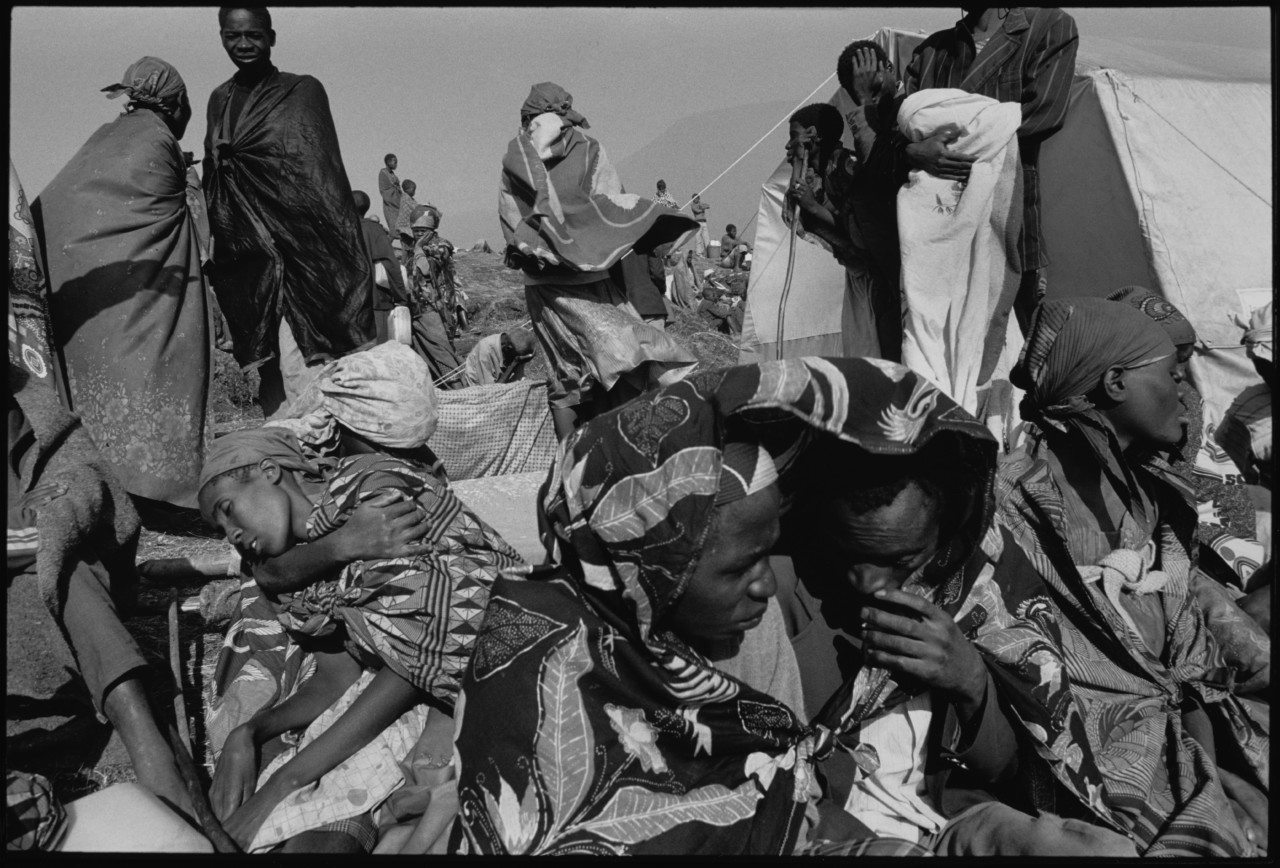

Having previously documented the horrors of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia the Magnum photographer Gilles Peress (Professor of Human Rights and Photography at Bard College, NY and Senior Research Fellow at the Human Rights Center, UC Berkeley) travelled to Rwanda during the genocide. His work there then became a book, The Silence, which – along with his previous title Farewell to Bosnia – forms part of Peress’ longterm project Hate Thy Brother – a photographic exploration of seemingly inescapable cycles of violence and hatred.

Of the genocide in Rwanda Peress has said, “The immensity of this crime is beyond our imagination and is only surpassed by the unbelievable indifference of the West and of the developed nations who would have been able to intervene and prevent the crime…”

Journalist Philip Gourevitch, a New Yorker contributor and staff writer and a former editor of The Paris Review, reported from Rwanda in the aftermath of the genocide. This work resulted in his first book: We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families. The book won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the George K. Polk Award, the pen/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction, the New York Public Library Helen Bernstein Book Award, and the Guardian First Book Award. We Wish to Inform You, examined the shocking events of the genocide, the historical and social factors that had laid the groundwork for acts of such brutality, and the aftermath.

Here we present Peress’ selection from his book The Silence alongside Gourevitch’s writing, and a selection of voices from his more recent reporting in the country.

Warning: this article contains graphic images

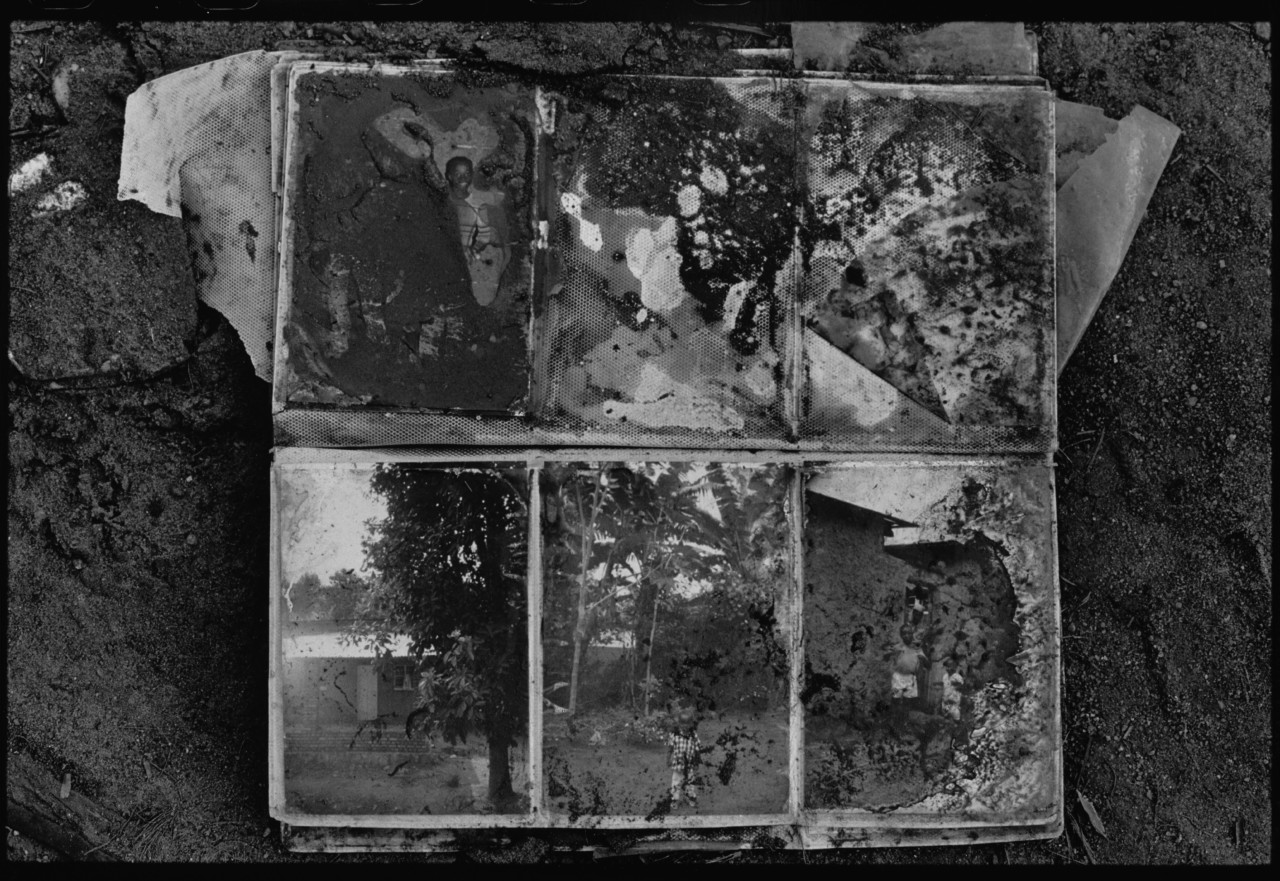

Gilles Peress published this work in 1995, a year after Rwanda’s genocide against the Tutsis, in a book he called The Silence. The title echoed in my mind off the equation made famous in the preceding decade of the Aids epidemic: Silence = Death. I had just returned from Rwanda, where I had visited the church massacre site at Nyarubuye, which had been left more or less the way Gilles found it, as a memorial. When my father read what I wrote about it, he referred me to this passage in Plato’s Republic:

“Leontius, the son of Aglaion, was coming up from the Peiraeus, close to the outer side of the north wall, when he saw some dead bodies lying near the executioner, and he felt a desire to look at them, and at the same time felt disgust at the thought, and tried to turn aside. For some time he fought with himself and put his hand over his eyes, but in the end the desire got the better of him, and opening his eyes wide with his fingers he ran forward to the bodies, saying, “There you are, curse you, have your fill of the lovely spectacle.”

It’s hard to look, and hard not to look. And that is as it should be.

Twenty-five years can feel like a long time, and like a moment ago. What you see here, in Gilles’s photographs still exists only because he photographed it, and because you’re looking at it. Everything that was then, remains only as memory. That’s life, and life = voices. Rwanda is full of voices, and the voices are full of memory. I’ve recorded some of them over time, and these are some things some of them have said in recent years:

Woman

Now there are paved roads. There are those little telephones. The young go to Kigali. But the big change we need here isn’t more cars or anything like that. The best change would be how people think. What troubles me is people’s heads. I can’t comprehend that someone used a machete to kill a person then used the same machete to kill a cow they ate. That means they ate human blood. They had become like hyenas. How can someone like that change, and come back among us?

Man

I was the one who brought him his food in prison. Everyone knew very well — the neighbors, the survivors — that I wasn’t myself a killer, just a child of a killer, carrying food to his father… I never broke the relation between us. It was tiring. I was ashamed. At times I even dropped out of school to bring him his food. But I wanted to do it. I didn’t choose my father… I chose to do that. I carried the food that he ate every day, but it was heavy. It was very heavy.

Man

The trials allowed us to understand part of the truth. But it hasn’t resolved all of our problems. The process is over, but the history continues. Because there was cynicism. Like, when I used to go asking after my father, everyone would say, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, we knew him, we knew him.” And when you say, “He was killed. What happened?” “No, I wasn’t there. I was sick. I was at the market.” Nonsense like that. But when the trials started, people said, “If they’re going to accuse me and I haven’t talked, it could create problems for me.”

Man

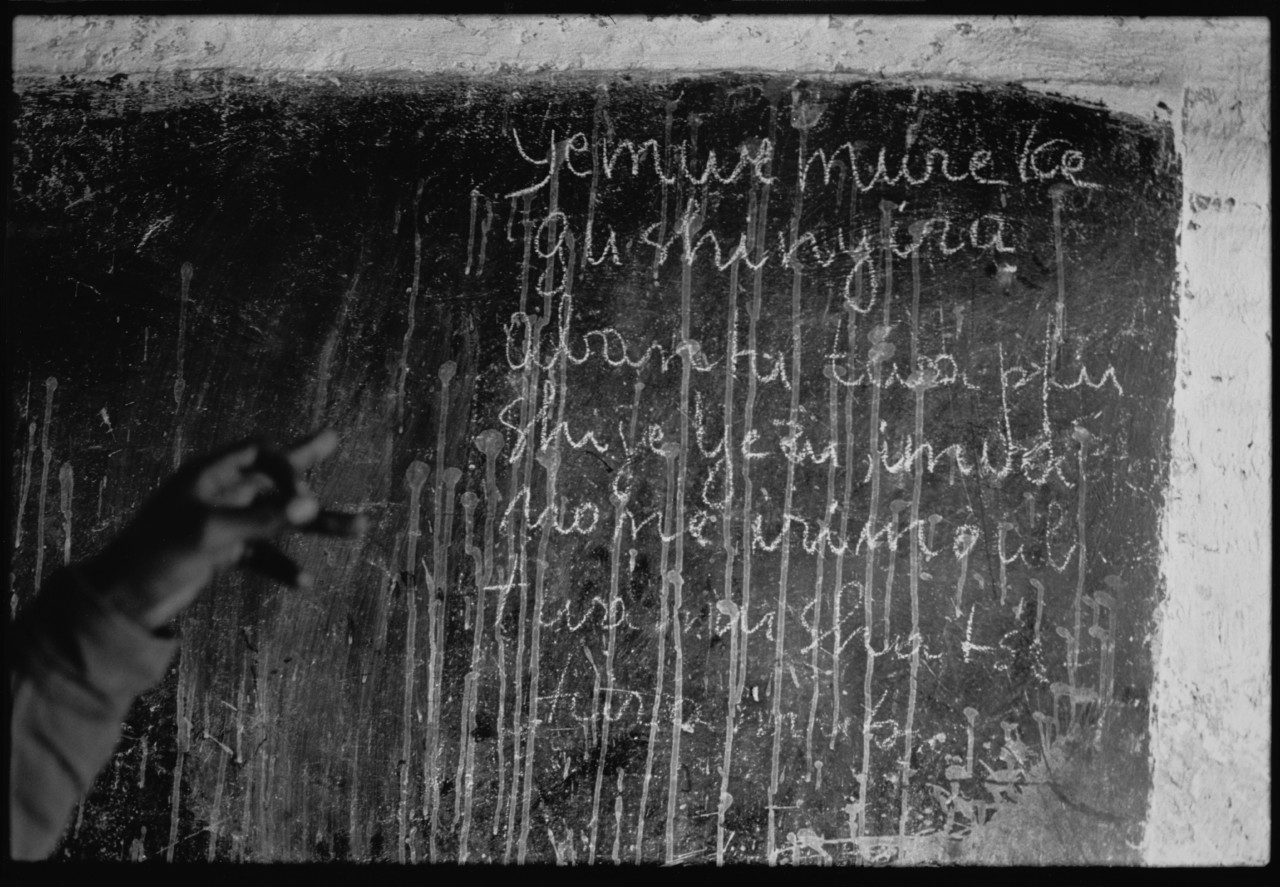

When we have a good government, the people is a good people. When you have a bad government, the people is bad. Because the people do the things the government teaches. The problem is not tribal.

Woman

“We had been submerged by the enormity of the crime, and everything became enormous after the enormous genocide — the massive flight to Congo, the things that happened there, the arguments it provoked, the years of infiltration and massacre, the two Congo wars. All things here have something enormous about them. It’s like when you open a mass grave — there’s always something enormous, but people must accept it as the most ordinary thing there is. Because without that, you cannot live. I was always struck by the banality, or ordinariness, of opening mass graves. One can open graves thinking there are two people and end up happening upon ten, thirty, a hundred, six hundred. It’s spoken about, but the next day, you move on. The grave is closed up, and you go farm beans or — voilà. You don’t dwell on it.

Man

I think mixed people got hurt a bit. I couldn’t get situated. What am I? What am I? I go to Hutu, they say you are not Hutu, you go to Tutsi, they say you are not Tutsi. It was a problem.

Two women

A: The right to abort is to be able to choose to have one’s child.

Z: Fine, listen, I’m for birth control. Use birth control.

A: You’re forgetting something. We’re in a society where sex crimes are so common.

Z: What does that mean!? What were the numbers in the genocide?

A: I don’t have to provide numbers that don’t exist.

Z: In this society, you would kill those children — you, who refused to have the killers sentenced to be killed?

A: I am, unfortunately, for the abolition of the death penalty.

Z: Ah! You see. And you are for killing the innocents?

Woman

What use is it today to be stuck with history? The genocide came to pass, it’s done, that’s it. There’s no choice. There aren’t many choices. The only choice we have is to live together again in a good atmosphere with the others. If not — if you create problems in your heart, you’ll always have torments. It’s better to calm yourself and give yourself peace. That’s the only way of getting over the thing.

Man

It is very hard to live ten twenty years with unanswered questions. It is traumatizing some people, when they have not found the body or the remains, and nobody has confessed. Like today, my wife does not have the right information when and how her father was killed. She does not know. For many years, people said maybe one day he will come back. And she passed so many years believing in that — that one day her daddy will come back. Imagine someone after five, ten, fifteen years believing in that.

The very bad side of the story is that there are some of the people she believes have information but did not say anything, and she cannot approach them and ask them clearly because she does not have the facts. Those are unanswered questions. But when we were commemorating for twenty years, I told her, you know, that conflict, that will keep troubling your heart. You better say he has gone in the same circumstance that others have gone.

Man

You can come and build a house here. Very beautiful house. And then I say, You see, this man is building a house because he took a lot of money during genocide. Because he killed so many people and he took their money. Now he wants to show me that he has money. And he comes to build a very beautiful house here near mine. So let me show him that even if my parents died, even if I’m still alone, I can work more than he can. So let me show him that I’m stronger than him. Then, if he made like 40 millions, you make 60, to show him that you are stronger than him. So that is just the kind of wars that we are facing these days. It is an indirect fight. You can’t touch him. You can’t say anything to him. But you are thinking of him.

Woman

On my mother’s side of the family there’s just one guy who survived — a son of a cousin of my mother, about my age. He’s like in a prison. He’s insane. He lives in Kigali. There was someone staying in his house here, then he came one day and evicted him, and said, Look, I don’t want anyone in my house, I want to destroy my house, and he planted trees, a forest all around it, and snakes came up inside. So he has a weird mind. You can see he hates himself, if you see what he says, if you see how he drinks beer. It’s almost a suicidal mind. No one survived in that place. He doesn’t care about making a bit of money – he just does whatever he thinks out of emotions.

Man

Did you see the little mouse? In Rwanda, we say if a mouse crosses your path, it means you have good luck.