Open See

Jim Goldberg on his seminal work documenting the movement of people to Europe through migration, immigration and trafficking

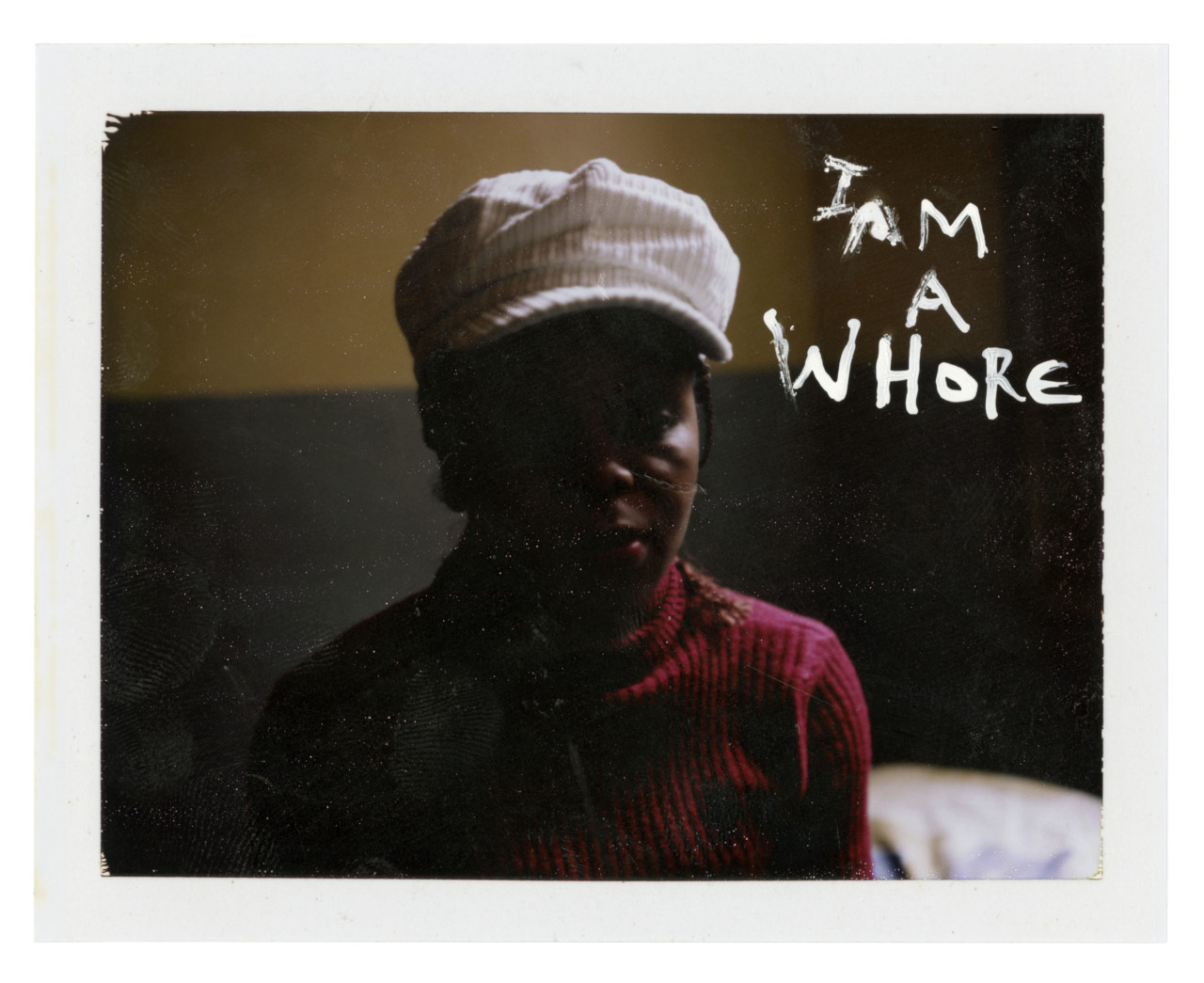

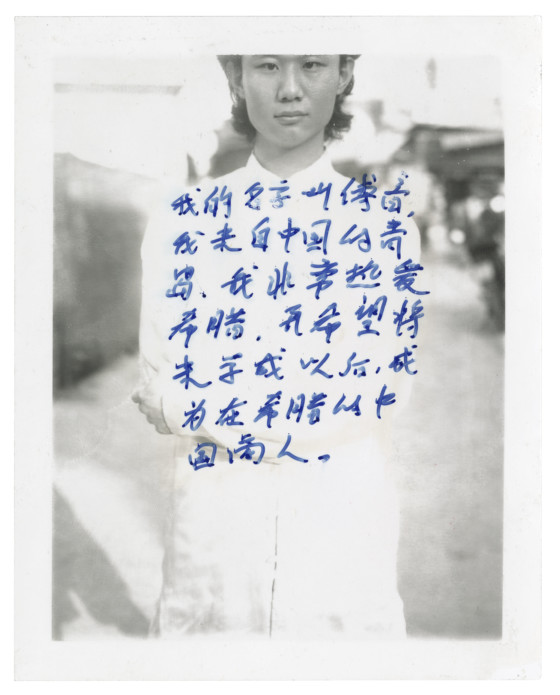

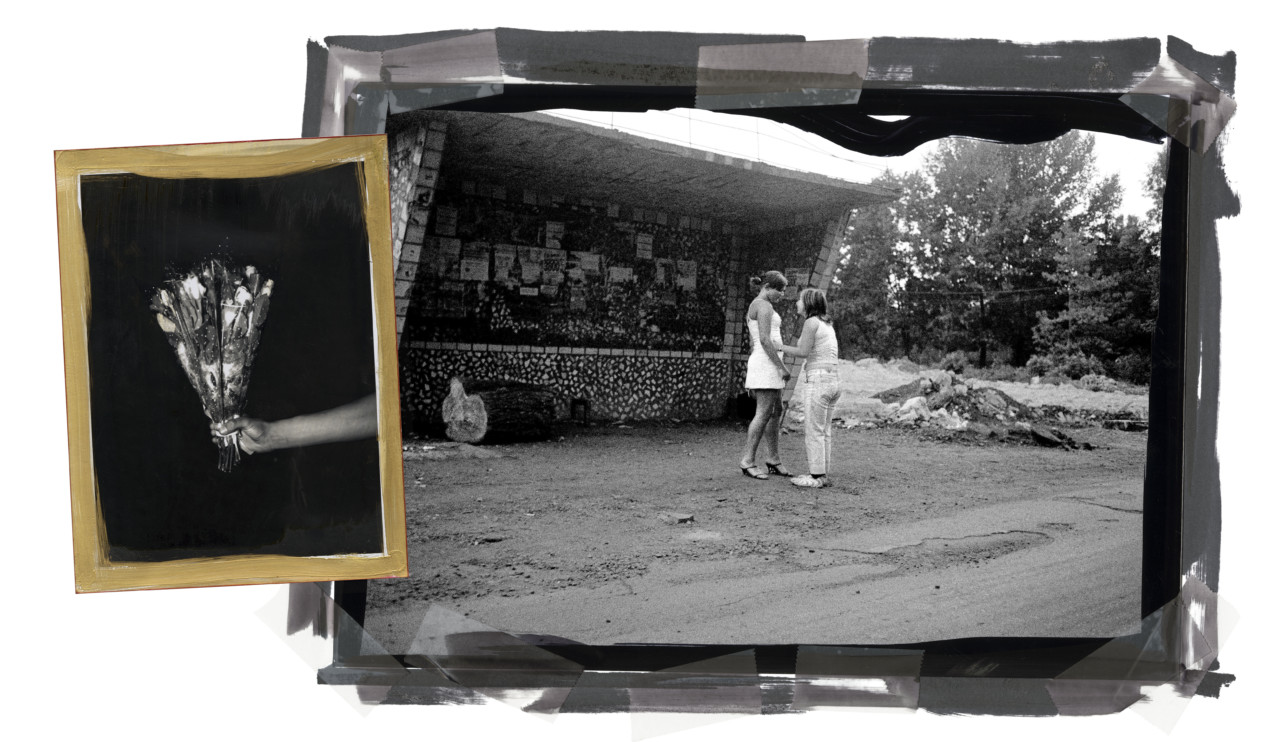

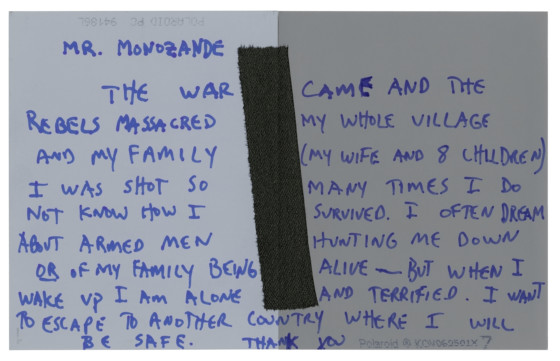

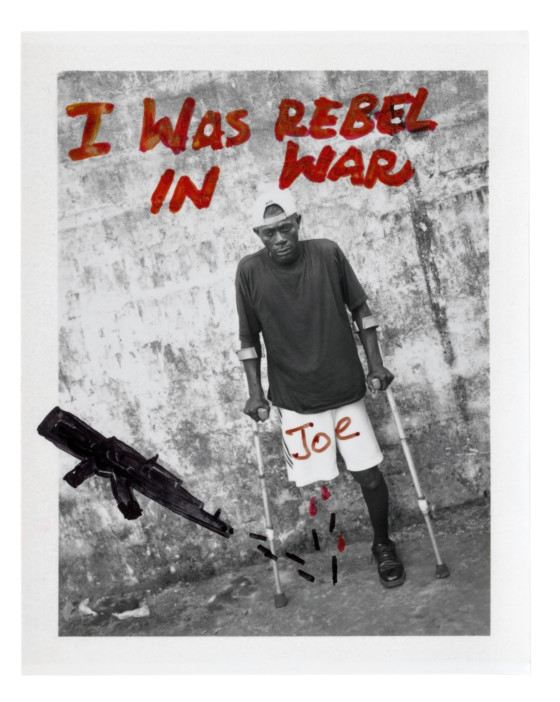

Through portraits, landscapes, and collaborative works, Jim Goldberg’s expansive Open See follows refugee and immigrant populations traveling from war-torn, economically devastated, and often AIDS-ravaged countries, to make new homes in Europe. The photographer spent four years documenting the stories of refugees in over 18 countries, from Russia and the Middle East to Asia and Africa. To convey a “more in-depth understanding” of the people he was working with, he tapped into a practice he had developed while in graduate school: hand finishing photographs, and including handwriting to tell the stories of his subjects, making each a unique object encapsulating a story

Here, Goldberg reflects back on this body of work, the processes he employed, and considers how the international migrant crisis has gone on to develop in the years that followed.

What was your original motivation for wanting to start the project?

Open See grew out of my first Magnum commission, Periplus, which consisted of eight photographers who were sent to document different aspects of Greek culture in the run up to the 2004 Summer Olympics. My focus during the commission was on the immigrant communities in Athens. After my first trip I realized I wanted to go deeper and that the project I wanted to produce was going to take some time to develop. Open See tells the story of refugees, immigrants, and trafficked individuals journeying from their countries of origin to their new homes in Europe. This project addresses the struggle of immigrants to leave conditions where war, disease, and economic devastation prevail. It also addresses their labors to adapt to new European cultures and the reciprocal efforts of those cultures to adapt to their new “citizens.”

"In 2003, when I started this project, migration, refugees, and trafficking were hardly on anyone’s radar"

- Jim Goldberg

On the people you photographed for Open See, do you know anything of their stories about how life has panned out for them since?

Most of the people I photographed were seeking asylum. I was told at the time that out of the 14,000 people who applied, only three were given it. Their lives were incredibly fragile, unpredictable, and transitory. I would meet someone one day, and they would be gone the next. Out of the hundreds of the people I met and photographed, there is only one person that I’m still in touch with.

"As more people are displaced, more doors are being closed to them than ever before"

- Jim Goldberg

In the ten years since Open See, how have you witnessed the circumstances surrounding migration change?

In 2003, when I started this project, migration, refugees, and trafficking were hardly on anyone’s radar. If anything, we know now that the problems have only gotten worse. There are over 65 million people displaced today, and another 21 million trafficked. Sadly, xenophobia has also increased exponentially–especially in this country. As more people are displaced, more doors are being closed to them than ever before.

Where might you focus your attention if you were looking to tell these stories in 2017?

One could certainly focus their attention on migration, refugees, and victims of trafficking right here in the U.S.

How do you imagine that work might look?

Impossible to say. The work evolves and adapts as the topic does. I also find myself experimenting with a lot of different media and materials these days.

What, in your opinion, is the role of an artist/photographer when it comes to the issues of the global migrant crisis?

My role is and always has been to figure out conceptual narrative strategies that can relate and retell the stories or situations that are going on in the world around me.

"The subjects become participants by retelling their stories, and the viewer perceives a closer connection through the honest word choice and handwriting they see"

- Jim Goldberg

Your work employs the technique of writing on the photographs themselves, which are hand finished, often with writing. As a device, why do you think this works so well for this type of project?

When I was in graduate school, I developed the technique of writing on photographs as another way to tell a story. Of course, it turned out to be something much more, something integral to my practice for 40 years. At the time, though, I certainly wasn’t thinking that far ahead. I just saw something that I felt I needed to make sense of, which is how most visual artists’ projects begin. Adding text to photographs created a better, more in-depth understanding of the people I was working with. The subjects become participants by retelling their stories, and the viewer perceives a closer connection through the honest word choice and handwriting they see.