Living in Limbo: How Refugees Are Reshaping Turkey

With Europe’s borders closed to asylum seekers, Turkey is grappling with the prospect that more than 3 million Syrians are there to stay

Magnum Photographers

When Turkey opened its doors to Syrians fleeing the first clashes of what would later balloon into civil war, the gesture was meant to be temporary. “Your victory is not far away,” Turkey’s then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan assured Syrians sheltering at a Turkish camp in 2012.

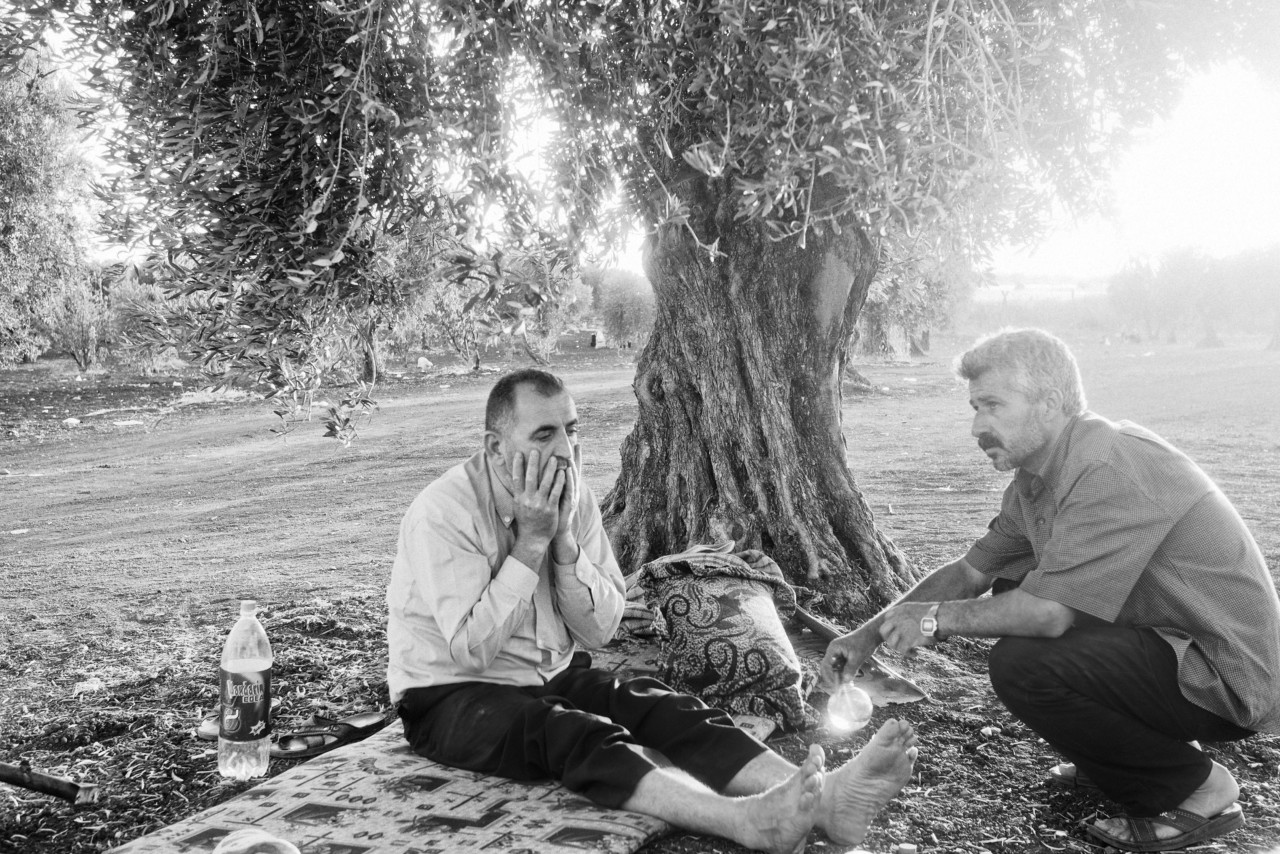

That year, Moises Saman visited one of the first refugee camps along the Turkish-Syrian border in Hatay Province. Most of the people he met felt they would soon be able to return home. “The villages were literally across the border and a lot of people thought they could go back at some point,” he says. “But as things dragged on, I think most people started to realize it was not going to be possible.”

The conflict continued to intensify and by the end of 2012, the number of Syrians in Turkey had blown past the limit of 100,000 refugees that officials initially said they could manage. Today, Turkey is hosting more than 3.3 million Syrians — more refugees than any other country in the world — and reckoning with the prospect that they are there to stay.

Over the last six years, Syrians have fanned out to every corner of Turkey, where they eke out livings in factories, on farms and construction sites. Those with means have opened businesses. Syrian bakeries, fast-food restaurants and community centers are now ubiquitous in some areas that, before the Syrian war, had just a small Arab presence, if any. A staggering 90 percent of Syrian refugees have foregone free housing in government-run camps in favor of a more normal and autonomous life in cities and villages. In some, like the southern city of Kilis, refugees now outnumber locals.

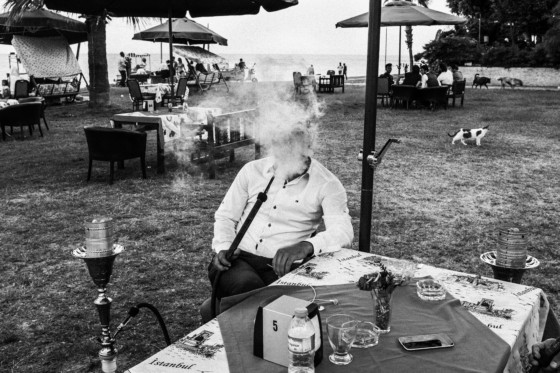

But the two groups exist in separate worlds, each frequenting different shops, cafes and even beaches. “Syrians and Turks generally don’t mix, but it doesn’t mean they don’t like or respect each other,” says Emin Özmen, whose photos from the southern cities of Mersin and Gaziantep provide glimpses of Syrian life in Turkey. “Many Syrian families told me how grateful they are for the Turkish people’s hospitality. Some of them showed me their televisions, carpets, other items given to them by their Turkish neighbors.”

But integration isn’t easy. Ankara, overwhelmed with the scale of the refugee crisis, took a long time to begin formalizing its approach to its Syrian “guests,” as it calls them. Until 2014, most Syrian children could not enrol in Turkish schools. Adults were unable to legally access the job market until last year. Turkish language courses are still neither mandatory nor easily accessible for most Syrians. Many have simply taken matters into their own hands, paying for private language lessons, finding off-the-books work and unofficial schools for their children.

Özmen photographed one that was run out of an ordinary apartment in the southern city of Gaziantep in November 2016. “All the rooms were full of children sitting on the floor, including the kitchen,” he recalls. Though the country’s education ministry had opened some courses to Syrian students by that time, Özmen says some families didn’t find the classes rigorous enough.

The lack of quality education and work opportunities for Syrians in Turkey — and elsewhere throughout the region, notably Jordan and Lebanon — prompted many to try their luck in parts of Europe, where there is stronger government support for refugees in terms of housing stipends, language classes and access to education and jobs.

Their rush to the continent peaked in 2015, when hundreds of thousands of Syrians joined a record wave of migrants trying to reach European shores. Through early 2016, a smuggling market flourished in plain sight from Istanbul down the Aegean Coast, transforming holiday towns and city squares into flashpoints in the global refugee crisis.

Saman found smugglers and refugees meeting with little discretion in the courtyard of an Izmir mosque. Özmen watched “tens of boats full of refugees” leaving the resort town of Bodrum in the middle of the night.

Syrians weren’t the only ones attempting the journey. Since 2011, Turkey has received more than 387,000 asylum applications, from mostly Iraqi, Iranian and Afghan nationals, whose plight has been overshadowed by the Syrian crisis. Hopeful for a better life in Europe, many joined the exodus of Syrians from the Aegean coast.

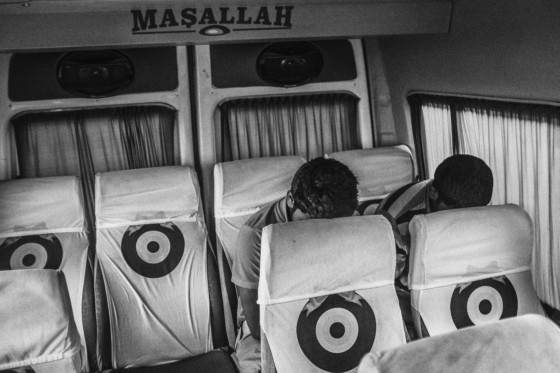

But the pathways to Europe abruptly narrowed in March 2016 when the EU, desperate to stem the flow of migrants to its shores, hatched a deal with Turkey. In exchange for European financial support (amounting to 3 billion euros) and other benefits, Turkey cracked down on smuggling routes from its borders. The deal has forced Syrians and other refugees with their sights set on Europe to face the reality that they’ll likely never get there.

"None of the young Afghans want to stay in Turkey, but many are stuck there."

- Newsha Tavakolian

Some Syrians will at least have the opportunity to be legally resettled in Europe. As part of the EU-Turkey deal, more than 3,500 Syrians were legally resettled in Europe as of March 2017—a tiny fraction of those who have applied for resettlement out of Turkey. Other Syrians will have the option of acquiring Turkish citizenship. In its most serious effort yet to integrate the country’s largest group of refugees, the Turkish government recently began granting citizenship to select Syrians.

Despite Turkey’s mounting problems at the moment — political instability, terrorist threats, social polarization and creeping anti-refugee sentiment — the prospect of Turkish citizenship still appeals to plenty of Syrians, who have lacked stability of any sort since fleeing their homes.

The same offer is not available to other refugee groups in Turkey, who find themselves increasingly isolated. In the summer of 2016, months after Turkey began closing off smuggling routes to Europe, photographer Newsha Tavakolian met a group of homeless Afghans in Istanbul. “Some of the young Afghan guys I met had jobs and would make a bit of money to survive, but many also could not find a job and had to sleep on the street,” she says.

“None of them want to stay in Turkey and look at it as a transit place,” she adds. “But many are stuck there and probably will never see the sky in Europe.”