On Girlhood in Gaza

Three young Palestinians describe their experiences growing up amidst conflict

Earlier this year Alessandra Sanguinetti, Lysney Addario and Esther Mbazi were sent on assignment to three locations internationally for Save the Children, for a photographic campaign titled The Female Experience of War. The project explored the structural challenges and human rights issues faced by young women living through conflict today. Sanguinetti’s chapter of the project focused on experiences of Palestinian children in Gaza, through the perspectives of three girls, Hana, Rania and Amani (names altered in body text and in image captions).

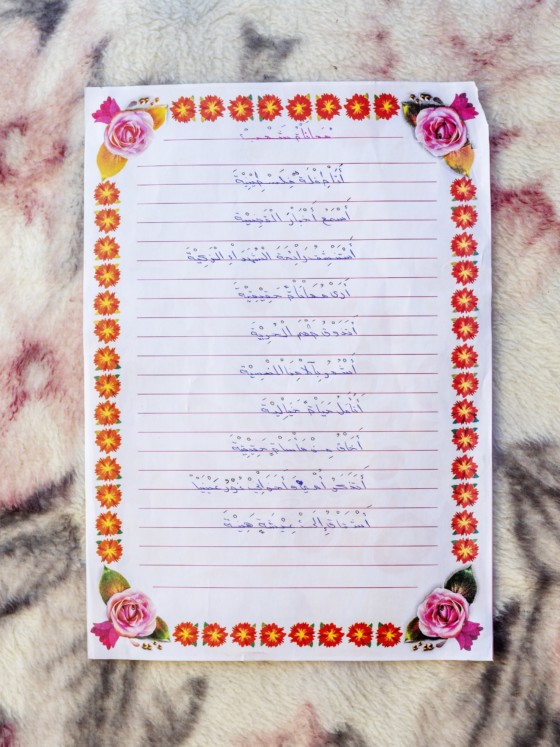

The girls were given writing prompts to respond to for this project, and each created a personal testimony in the form of poetry or prose. Sanguinetti captured the young people’s work in the form of diptychs, which pair them with the portraits of their authors. Here, Save the Children’s Picture Editor Nina Raingold explains how the project came together and why photography plays such a vital part in advocacy for young women’s rights. Below the interview, we share the diptychs together with their English translations.

Are the issues suffered by young women and girls in conflict zones under-represented? If so why?

This project was inspired by a report which found that girls are disproportionately affected by the horrors of war. More than 200 million girls live in conflict zones, and inequalities with boys are magnified during conflict making them more vulnerable to sexual violence, forced early marriage or the denial of basic rights including healthcare and education. Girls who are forced to marry young or who have to stay at home and help with domestic chores are likely to be far less visible and without a platform to be heard. As a result, girls worst affected by growing up in conflict are wholly under-represented. This project has allowed us to draw attention to these important stories which are rarely told or heard, and to give these girls the platform to speak directly about their struggles, their hopes and their dreams.

Why is it important to have visibility on issues of children’s rights through photography?

Crucially for Save The Children, documentary photography connects our audiences to the families we help and allows us to highlight the injustices that children around the world are facing. Considered and sensitively captured photography means that we are able to tell important stories and make them relatable, without overwhelming audiences with the brutality of children’s experiences and what it means to have your rights denied.

For The Female Experience of War, a ‘day-in-the-life’ approach enabled us to capture everyday routines that are universal to everyone. As the harsh reality of what these children face is slowly revealed, the photos take on a deeper meaning. We realise the true sense of their struggles, as well as their incredible resilience. A set of sensitively executed images like this, which strike a delicate balance between the painful truth and a sense of hope, can have the potential to genuinely resonate with people and bring about change.

What was the motivation for exploring poetry and written testimonies and what was the process for creating the poems? And why is it important to centre the voices of the young people affected by the issues?

Nothing is as powerful and direct as the voice of the child. The idea for the poems came about through discussions with the Creative Team at Save The Children about ways to help the girls retain their agency and speak for themselves. This is a technique that is often used in participatory workshops when trying to enrich stories. We also wanted to succinctly tie the experiences of girls from three different countries together, through one common technique exposing the reality of war.

We asked the girls to explain war to a child who has never experienced it, using a ‘sense poem’ framework to finish sentences we’d started, such as ‘I hope… ‘ or ‘I miss…’ or ‘I remember…’. Some of the girls, Rania* for instance, chose to write prose instead.

All the pieces are insightful and overwhelmingly powerful. The girls refer to a broad spectrum of their lived experience – from small details such as the food they eat, to the huge emotional void left by losing family members. Paired together in diptych format, portraits alongside the texts give us a better picture of each story than any single image could.

Amani

I heard the sound of explosions in the war.

I smell phosphorous and the smoke from fires.

I saw the fighter jets of the occupation and people were frightened.

I tasted rice at school daily, with no money or clothes.

I felt fear, exhaustion and anxiety about what would happen later.

I wish my country was not occupied and I could travel to other countries.

I hope our country becomes unoccupied, free of fear and that it was safe. God willing, it will return to us, for sure.

I remember when my family and I left our homes to the school, we were frightened and anxious. We wish we could go back to how we used to be.

I miss my childhood that has gone and which I have been deprived of.

Hana

I am a Palestinian girl

I hear the news of our cause

I breathe in the beautiful scent of my family

I see the real suffering

I taste the flavour of freedom

I feel our forgotten pain

I imagine an amazing life

I fear a real catastrophe

I remember my mother and brothers, the light of my eyes

I miss a blissful life

Rania

In the summer of 2014, after my dad had re arranged things to sort out stability for our family, we woke up to the sound of bombs and explosions, as the Israeli occupation on Gaza [had started]. Our area was one of the most affected areas by the hostilities.

At the start of the hostilities, our area was exposed to a missile, then I began to hear bullets from the fighter jets and tanks so we got out, running, frightened; we fled our house dressed in our house clothes to our relatives’ home who lived in a safer area compared to our place. A month after the war, there was a ceasefire and we went back home to check on the house. We found the whole neighbourhood was destroyed, there was the smell of blood, bodies everywhere, until we reached our home and we found it had been hit by a bomb that destroyed my room. All my toys, clothes and memories were lost when our home was destroyed. I began to scream, with tears running down my face. I tried to remember how my room looked like, and I would smell my clothes that smelled of gunpowder.

My father used to work as a tailor in a factory in al- Shuja’iyya, but it was bombed in during the war and from then onwards my suffering and that of my family began. No one was able to get another job, debts began to accumulate, he [dad] was unable to provide me and my siblings with the minimum of our needs, so I and my brother left our education behind, because Dad was unable to provide the minimum requirements that we needed. I felt my future had stopped and was lost…I began to help my mum with housework. My sisters were married at 16, they left school so they could relieve dad’s suffering.

My life lost its purpose and its meaning. Days would pass followed by dark nights.

Until the protection coordinator in the emergency project Ahmad al-Ruzi came to see my older brother who had been injured in the ‘Return’ marches. When he asked about our family situation, he discovered that I had left school and that mum had been considering marrying me off and that I wanted to leave this miserable life. I rejected marriage as I could see the suffering of my married sisters, but mum wanted to relieve dad’s burden by getting me married… Until I met the case manager Iman al-Sayed and after that I met with the Specialist Psychiatrist. They gave me back hope in life after the case managers Iman al-Sayed and Husam Radwan sat with mum and convinced her to go back of her plans of marrying me off.

Then they sat with dad and my uncles, and after more than three weeks, they were finally convinced to forget about having me married.

Then I began to feel that life could return. They helped me at the Family Centres to get back my childhood and my studies. I took part in individual sessions as well as group ones with the psychiatrist and then my dreams and personality began to return where I changed from a shy child, refusing to go out of the house to a girl thinking about her future and the future of all girls that were oppressed by their lives. I began to feel that I had challenges facing me but also dreams I must fulfil, the first of which is to become a lawyer that defends oppressed girls and girls abused by their communities and families. I also hope to show this to all communities across the whole world as well as showing them the suffering that girls in Gaza live due to the siege, wars and traditions. It has become my duty to deliver my experience to other girls and to the people in the rest of the world who think that we are a people that does not love life; in fact, we wish for beautiful lives to be a reality. Not just something we see only in our dreams.