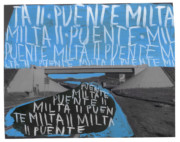

Thomas Dworzak’s Khidi – The Bridge

Giorgi Lomsadze reviews the photographer’s new book, a film script accompanied by nine years’ worth of documentary photography, exploring comedy and tragedy in the war against Afghanistan

Fiction can be truer than history, Thomas Hardy said, and that applies to Khidi – The Bridge. Although set in an unnamed warzone, the book reflects the emotional truth of Georgian soldiers’ experience in Afghanistan and Iraq, and is based on photographer Thomas Dworzak’s accounts of being embedded with the Georgian troops in these two countries. It was the authors Jeroen Stout and Ineke Smits’ creative choice to use fiction as a vehicle and a film script as a narrative form for this story. The cross-cutting between Dworzak’s fascinating photography and the authors’ vivid prose indeed provide for a cinematic reading experience.

The book comes just as the Americans called it a day on the “forever war” and offers an unlikely yet fitting epitaph to it. Khidi – The Bridge takes a look at the war in Afghanistan from the perspective of a small country with a little immediate reason to be in a war waged by the major powers.

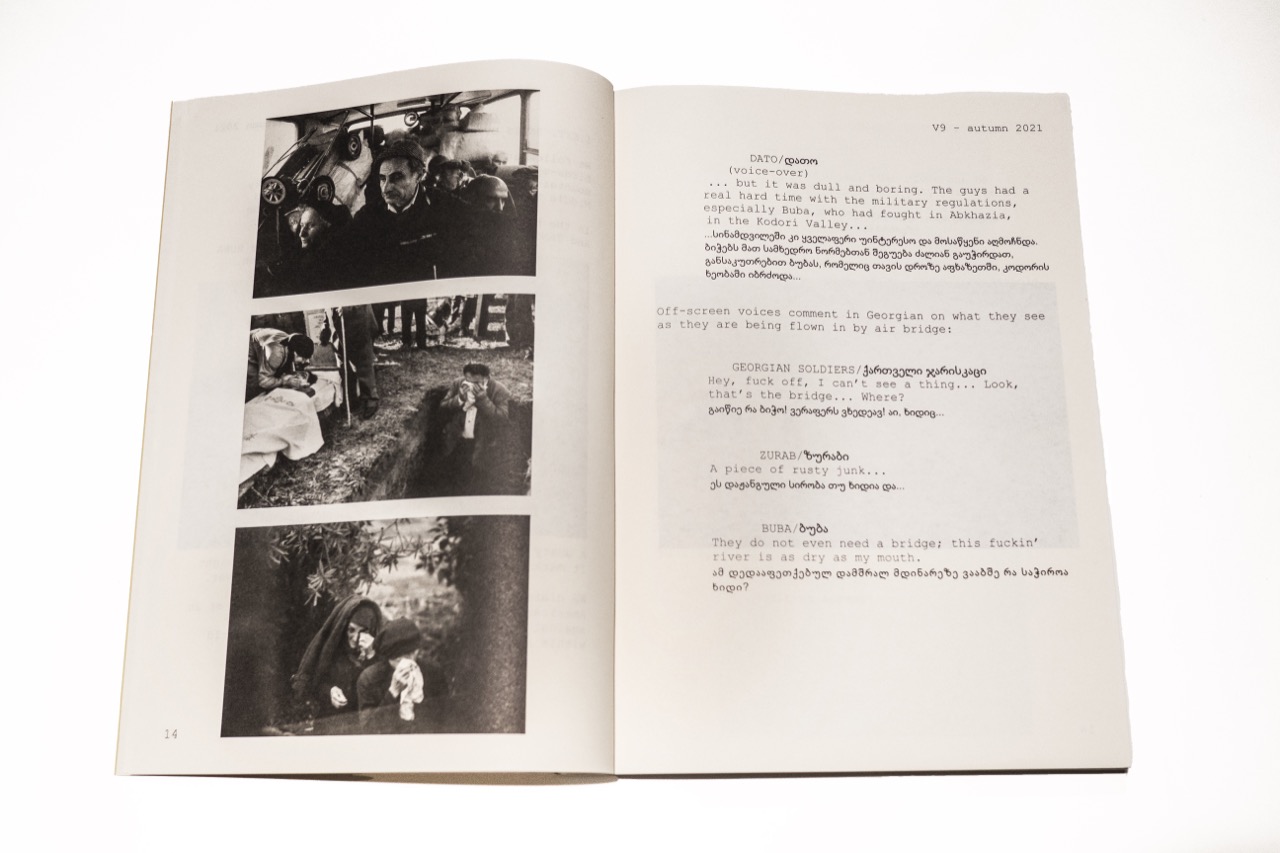

The story goes largely as a POV shot from the viewpoint of protagonist Dato Shervashidze, a moustachioed, straight-laced captain in charge of a rowdy team of fellow Georgians, who have little appreciation for military discipline. This includes a chaplain, who smuggles wine into a military base for religious rituals, and Buba, a seasoned soldier and no less seasoned foodie, who tries to ferment juice into wine using a microwave. The characters may come off as grotesque exaggerations to readers with no experience with Georgia and especially Georgian supra – a traditional feast that is the pillar of Georgian culture.

Stout and Smits, whose day job is filmmaking, teeter-totter between comedy and tragedy throughout the book. This is also how Dworzak remembers his time with Georgians in Afghanistan, where zany situations were followed by tragic ones. “This one time, a Georgian commander and I left the base and went into different directions. He was killed and I made it out,” Dworzak said.

The Bridge is primarily about Georgia. Stout, Smits and Dworzak share fascination with the country. “Thomas and I have known each other for years and we share the same (sometimes critical but always fond!) appreciation of Georgia, its people and culture,” said Ineke, who splits her time between Rotterdam and Garikula, a small town-turned-creative retreat in Georgia.

Dworzak and Smits’ professional paths have crossed in Georgia many times – once Dworzak was taking photos of Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili and at the same time Smits was working on a documentary about Saakashvili’s wife, Sandra – but they had never collaborated until The Bridge. “First, I interviewed Thomas couple of times to collect his stories,” Smits said. “On the bases of those stories and a broad idea Thomas already had, we started to develop the characters and write the script.”

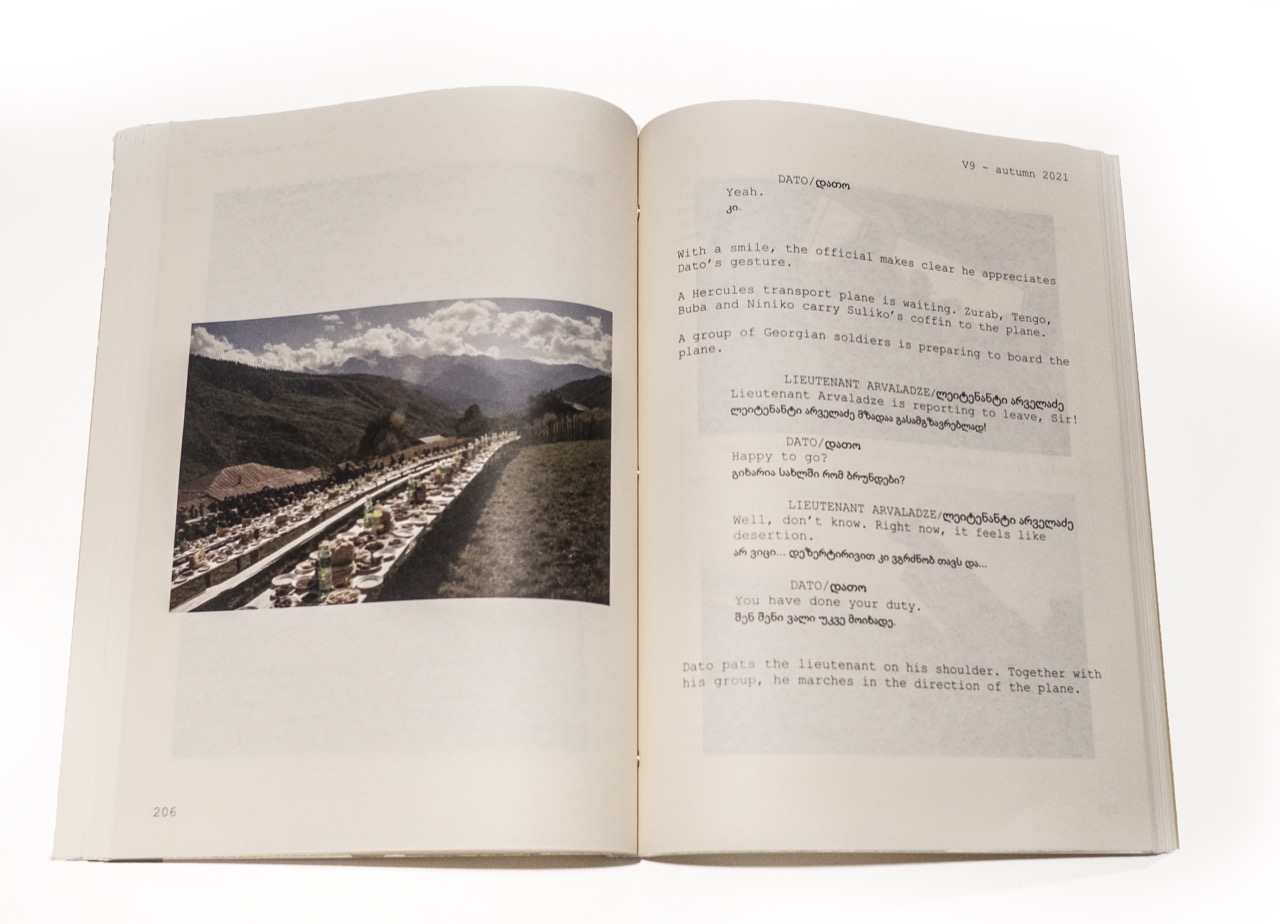

While in many ways an Emir Kusturica-esque burlesque, The Bridge also excels at capturing the quotidian side of war, the daily routine of soldiers stationed in a far-off military base. While pursuing their mission with fervor, the characters have to wonder what they are doing in a faraway desert, protecting a troubled bridge with no water under it to speak of.

Skype conversations between Shervashidze and his diplomat wife explain the Georgian agenda: contributing troops to the Afghanistan and Iraq campaigns is meant to bring Georgia closer to NATO membership, which the country views as a shield against its nettlesome neighbour, Russia.

"Georgia in fact has a neck for getting stuck in big powers’ expeditions in Afghanistan."

- Giorgi Lomsadze

Georgia in fact has a neck for getting stuck in big powers’ expeditions in Afghanistan. At the turn of 18th century, Persian shah tasked his imperial subject, Georgian King Giorgi XI, to quell an Afghan rebellion. Commanding a small army of fierce Georgian warriors, Giorgi led a successful if brutal campaign and was eventually made the shah’s viceroy in Kandahar.

Giorgi and his men eventually met their deaths in the house of an Afghan chieftain, who lured the king and his escort to a feast. A description of the assassination by the king’s loyalist and historian Sekhnia Chkheidze brings to mind the scenes from the Blood Wedding episode of the Game of Thrones series.

“When the king got wise to it, he reached for the bow and, praise be, did not miss a single shot until he had arrows to shoot,” Chkheidze wrote in his chronicle, The Life Of Kings. “He fought like giant, but they shot at the great lord from a gun and killed him …They went into the fortress of Kandahar, looted it and massacred all Georgians therein.”

Almost 200 years later, Georgia’s other overlord, Russia, sent Georgians to the Soviet-Afghan war that came as a part of Soviet Moscow’s pastime of installing loyal socialist regimes around Soviet borders. The Bridge alludes to the war through one of the characters, Zurab, whose uncle fought in the 1970s-80s Soviet campaign in Afghanistan. “He could have warned me,” Zurab says. “What can you do around here? No liquor for sale, not anywhere, and the girls…”

Moscow tried to keep the heavy human toll of the war under wraps up until the Soviet Union began falling apart. “Seventh year into it, we knew nothing about the war save for the tales of heroism we’ve heard on TV. Only the arrival of the new batch of zinc coffins would catch our attention,” Belorussian writer Svetlana Alexievich wrote in her famous 1989 book, Boys in Zinc.

Then Georgia finally joined the US-led “forever war” in 2004, this time of its own accord and in search of belonging in the world. “You have this country that wanted to establish itself with the Western powers by going to their war,” Dworzak said. “Georgia is in-between and there was very little ‘September 11 spirit’ there. You’d think it would be hard to convince a guy from Kharagauli [a small town in western Georgia] to go to war in Afghanistan, but it did not take much convincing. And guys there were really invested in it.”

"Georgia is in-between and there was very little "September 11 spirit" there."

-

In Khidi – The Bridge, Georgian soldiers vicariously fight Georgia’s own domestic battles. “For Ossetia, for Abkhazia!” they scream as they shoot at the jihadists who’ve never heard of the said breakaway territories.

There is a twist that brings the story closer to home for the protagonist. That episode in the story brings to mind a 1958 Georgian film Mamluk, a story of two Georgians, who as little boys were best friends but got separated and eventually found themselves serving in rivaling foreign armies. This was a bit of a spoiler, but despite it, there is plenty to read, see and think about in The Bridge.

Giorgi Lomsadze writes Tamada Tales, a blog that tracks social, political and economic trends in the Caucasus region of the former Soviet Union.

Khidi – The Bridge is available to purchase here.