War Games

Thomas Dworzak explores contemporary representations of conflict in France

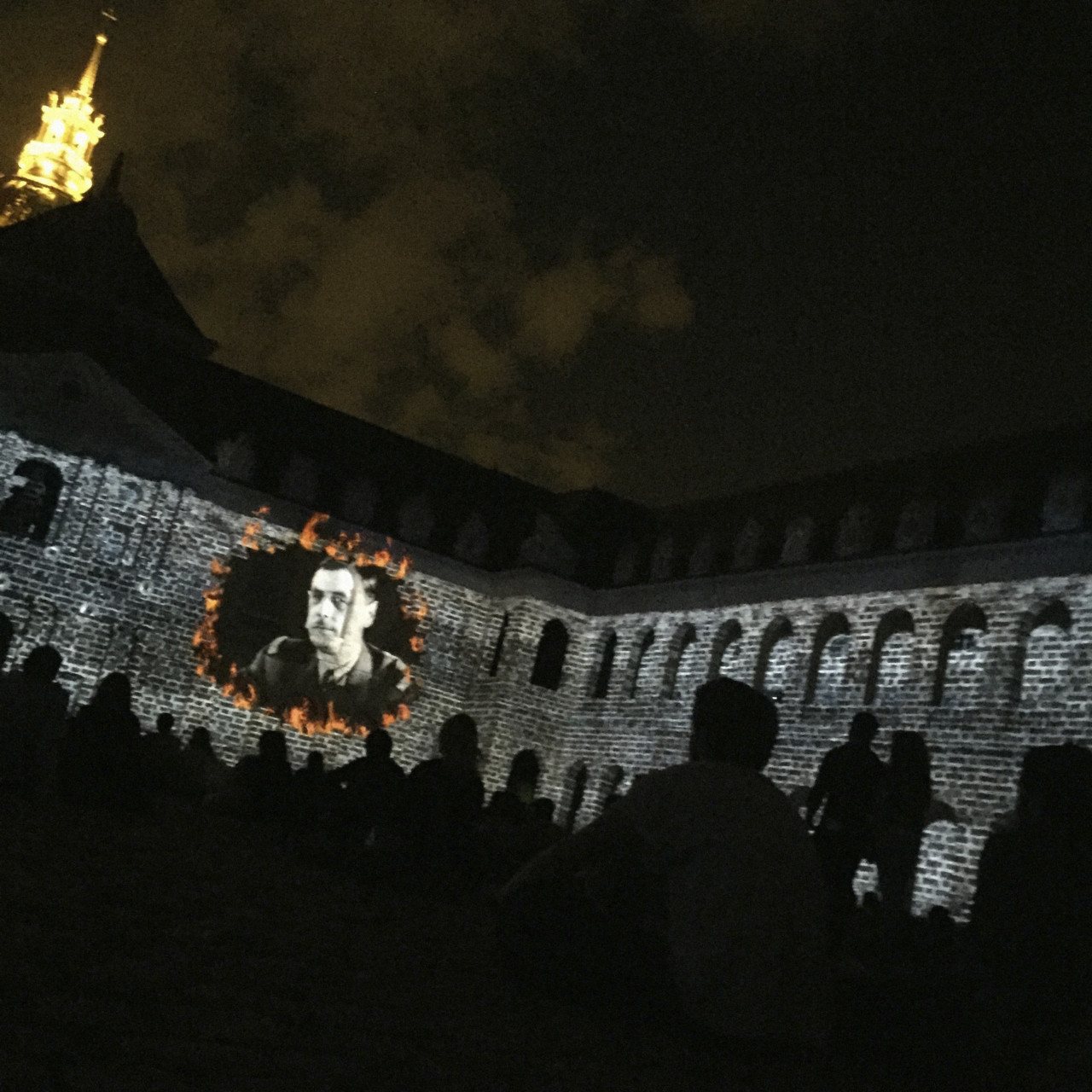

Straddling reality and fiction, fact and fantasy, Thomas Dworzak’s War Games project examines the topic of security and the military in France today. Since the attacks of 2016, France has been under a State of Emergency, making this topic both poignant and pertinent. From re-enactments to anti-terrorism training and film sets, Dworzak explores the iconography of conflict and its consequences.

What drew your interest in war games, and how did you begin this project?

I have been toying around with the idea for a while. A few years ago, I spent a few weeks photographing the training of troops before they deployed to Afghanistan, and for the first wing of my WW1 story spent some time with re-enactors. Those two aspects, training and the historical context are in a way at the core of my interest. As part of Magnum’s long-term investigations into the state of France, I chose to pursue the notion of war games further in France, the year before the elections.

The training sessions in hostile situations look particularly intense. What kind of simulations did you photograph? What is happening there exactly?

In these images, French diplomats spend a few days at a military base and are mock-kidnapped and interrogations by “terrorists” are simulated in stressful environments.

The training sessions of the GIGN, an elite law enforcement and special operations unit of the French National Gendarmerie, are modelled after events that occurred in real life, some of which I covered as a photojournalist.

From parades or commemorations to re-enactments and TV shows, simulations and training for hostile situations, and the gamification of conflict, the iconography of war has, for a long time, played a certain kind of role in our society – and our personal mythologies. Can you define this role further? What is the purpose of representations of war?

Volumes have been written about how certain games make players more violent, others create awareness. I am trying not to have an opinion about this. Rather, I want to play with these different aspects, memories, ambiguities, confusions.

I don’t think there is any specific way of representing war in our time now.

Why does it matter to photograph war and its many representations?

Ultimately, of course I think it’s important that “we” continue to document wars. It is not a solution to just photograph the “fake” versions of it, in the same way that feature films cannot replace documentary, novels reportage etc. But right now I chose, for this specific body of work, to photograph the “fake”. I hope it adds a little bit to the doubt and the confusion to our perceptions of the “real”. And that’s what matters to me.

You have a long-standing interest in the representation of conflict. How does this work fit into your wider practice?

It stretches my possibilities. I can include historical events into my work: being less of a slave to the moment. And, as I said before, what I care about the most is that, hopefully, this work triggers more confusion and doubt about the real–and also about my other work!

This story is part of The France Project: perspectives on the social, political and cultural landscape of contemporary France. In this ongoing project, initiated in 2016, Magnum photographers explore the background to issues influencing debate in the country in the run-up to the election. See more stories from this project here.