The Korean War: Behind the Battlefront

On the 70th Anniversary of the Korean War Armistice, Werner Bischof’s work stands as a powerful reminder of the human cost of the conflict, which marked a pivotal moment in the photographer’s practice

On June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea, marking the start of the Korean War. What followed was a savage conflict that claimed the lives of millions. The invasion followed the intensification of low-level fighting, which had been taking place along the two countries’ temporary border for years. Korea had been divided at the 38th parallel following the end of World War II; the Soviet Army took hold of the North, while US forces established control in the South with a view to eventually unifying the country. Both occupying powers established civilian regimes. However, ongoing resistance from the Soviet Union and North Korea’s new leaders towards attempts at forming one government ensured that Korea remained split.

One year into the fighting, Werner Bischof journeyed to the region to investigate the human cost of the conflict, having just completed an assignment for Magnum in India. On the 70th anniversary of the armistice agreement that halted the hostilities and left Korea divided down a de facto boundary that still exists today, we look back at Bischof’s historic coverage of the war.

Bischof had been invited to join Magnum in 1948, following his extensive documentation of life across Europe in the aftermath of World War II. This was a transitional moment for the photographer who had received an art school training and originally intended to become a painter. Although he did not pursue this route, Bischof began his photographic career working in a studio, creating beautiful images dominated by natural forms and abstract shapes.

However, the experience of documenting post-war Europe made him question his role as a photographer and he became committed to using the medium as a tool for social change. He officially joined the agency in 1949, alongside its four founding members. Moving away from his fine art roots, Bischof continued to embrace a more photojournalistic approach and, from 1951 to 1952, dedicated himself to documenting social and political issues across Asia.

"His photographs had a tendency towards the absolute — a combination of beauty with truth"

- Ernst Haas

The photographer’s first stop was India, where he worked on a number of projects including his renowned photo-essay Famine Story, which shed light on the severe famine ravaging the country. Bischof soon became set on traveling to Korea, determined to expose the suffering of civilians caught up in the war.

On the morning of July 5, 1951, he joined ten other correspondents from around the world on a flight to Seoul. “I just had to see for myself how this war was being conducted. (Something else was at play too: I found it important to show the human, the civilian side of the story. The Koreans who were chased out of their homes,)” he wrote in a letter to his wife, Rosellina Bischof, sent from Tokyo on July 11, 1951.

Despite making the transition to photojournalism, Bischof’s relationship with photography remained complex. He particularly struggled with the realities of being a photojournalist and was angered by the prevalence of, what he regarded as, sensationalistic and careless reporting. In the same letter to Rosellina he described his first impressions of Seoul: “Among these ruins, the press center shone as the sole lit block, hundreds of journalists. It seemed to me as if we were vultures on the battlefield, always out for the sensationalistic …” However, it was a desire to go beyond the shocking images strewn across newspapers’ front pages that drove him on. So, as he had done in India, and post-war Europe before, Bischof looked beyond the immediate and produced a poignant documentation of those behind the battlefront.

"It seemed to me as if we were vultures on the battlefield"

- Werner Bischof

This deeper and more considered approach to reporting is a defining characteristic of Magnum photographers, but one that was shaped by Bischof’s artistic background too. “I always and in every way go too deep into the subject matter, and that is not journalistic,” he wrote in a letter to Robert Capa, sent from Tokyo on September 9, 1951.

His artistic roots had also equipped him with an appreciation of beauty, which Bischof translated from his studio work into his documentary practice, including the work he produced in Korea. “His photographs had a tendency towards the absolute — a combination of beauty with truth: a stone became a world, a child was all children, a war was all wars,” observed the photojournalist Ernst Haas, an early Magnum colleague.

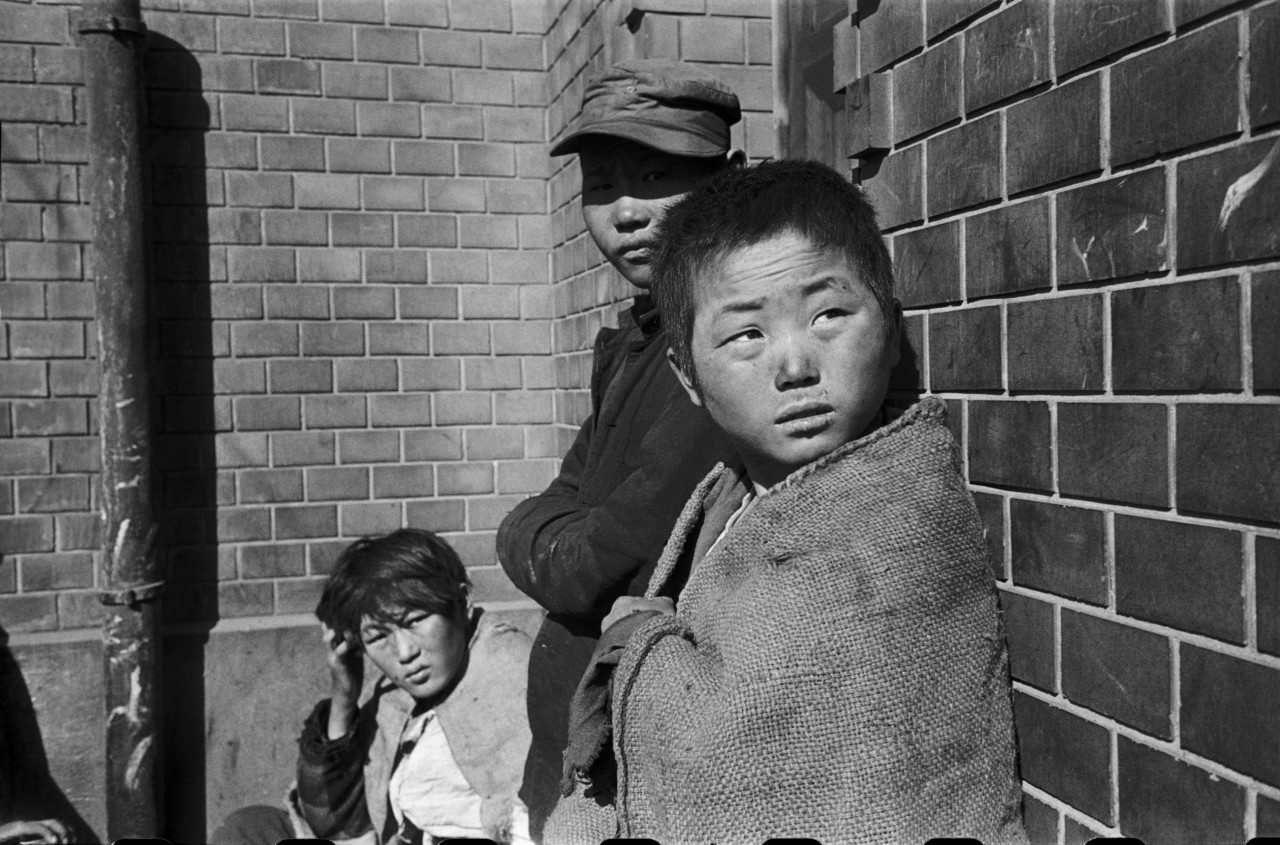

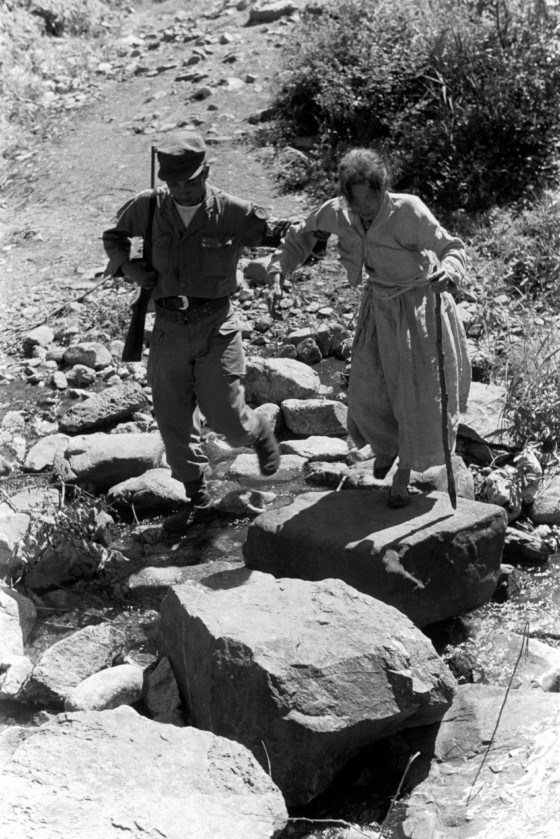

The Forgotten Village

After investigating war-torn Seoul, Bischof traveled to Sanyang-ri, a small village nestled in one of the many valleys of central Korea; an area that had become a no man’s land for troops in battle. “Not a single native Korean male is tolerated in this war zone, not a woman, not a child, only soldiers,” observed Bischof in the report for Magnum Photos, dated July 8, 1951, which he wrote to accompany his images. Bischof accompanied a small Civil Assistance group as they evacuated the inhabitants of this forgotten village. As was the photographer’s intention, the resulting photo story sheds light on the harsh realities for civilians caught up in the conflict.

In his report, Bischof described the desperate scenes he encountered: starving and ill civilians, many of whom were reluctant to leave their homes. The Civil Assistance group moved from house to house, providing clothes, food and medical help. Bischof followed, photographing and making notes as the team evacuated the village and brought its inhabitants to a nearby rendezvous, where they received further assistance.

“In front of another house, a small skeletal body sits in the dazzling sunlight, crouches naked on the floor, absolutely covered in flies. Near to her, her sixteen-year-old brother is unable to use his limbs. A shaven-headed figure in the hut takes no notice. We think it is a child, but the interpreter says it is a thirty-year-old woman,” reads an excerpt from the report.

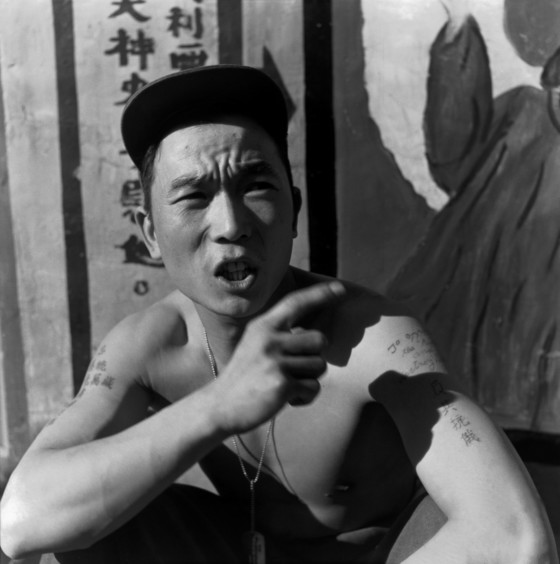

Prisoner’s Island

In January 1952 Bischof reluctantly traveled to Koje-Do Island in South Korea to document a United Nations re-education camp for Chinese and North Korean prisoners. On hearing the news that a number of prisoners had been shot, a colleague he was traveling with urged him to go. “I was against it, but John thought it very important — so we flew off, as if it were a Sunday excursion, journalists from around the world, joking cheerful,” he wrote.

The camp was spread over a large area spanning two valleys and was home to around 160,000 North Korean and Chinese prisoners at its height. Journalists were able to explore relatively freely, but were prohibited from talking to inmates.

"We cannot deny that what we are doing here is political manipulation"

- Werner Bischof

Bischof characteristically focused on the prisoners, creating a series of images documenting their everyday lives and the United Nations attempts at reeducating them. His writing from the trip sheds light on his critical views of the situation: “We cannot deny that what we are doing here is political manipulation and an attempt to make these people grasp the ideas behind our own view of life.”

The photo story was subsequently published in LIFE in March 1952. Bischof’s negative reception of the editors’ selection of images reflected his issues with photojournalism more broadly: “It is difficult to take photographs in a prison camp, to hold onto your humanity, and subsequently to have the best pictures discarded by the censors. I sometimes ask myself whether I have become just another “reporter,” a word that I have always hated so much.”

Bischof was deeply affected by the suffering he witnessed in Korea. His images stand as a powerful testament to the massive civilian cost of the war, which remains unresolved to this day. Following his work in Korea, Bischof went on to spend five months in Japan, before traveling to Hong Kong, and then on to Indochina. He remained committed to photography until his untimely death in a road accident in the Andes on the May 16, 1954.