Documenting the Dromedary Camels of Mauritania

The United Nations declared 2024 the “International Year of Camelids.” In January 2025, Zied Ben Romdhane traveled to Mauritania with the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to highlight the importance of camelids for the socio-economic progress of the local community

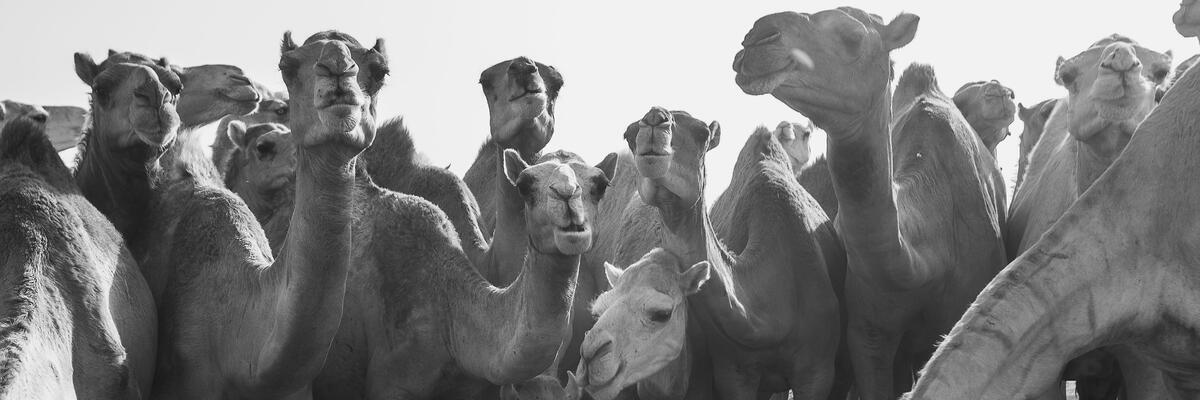

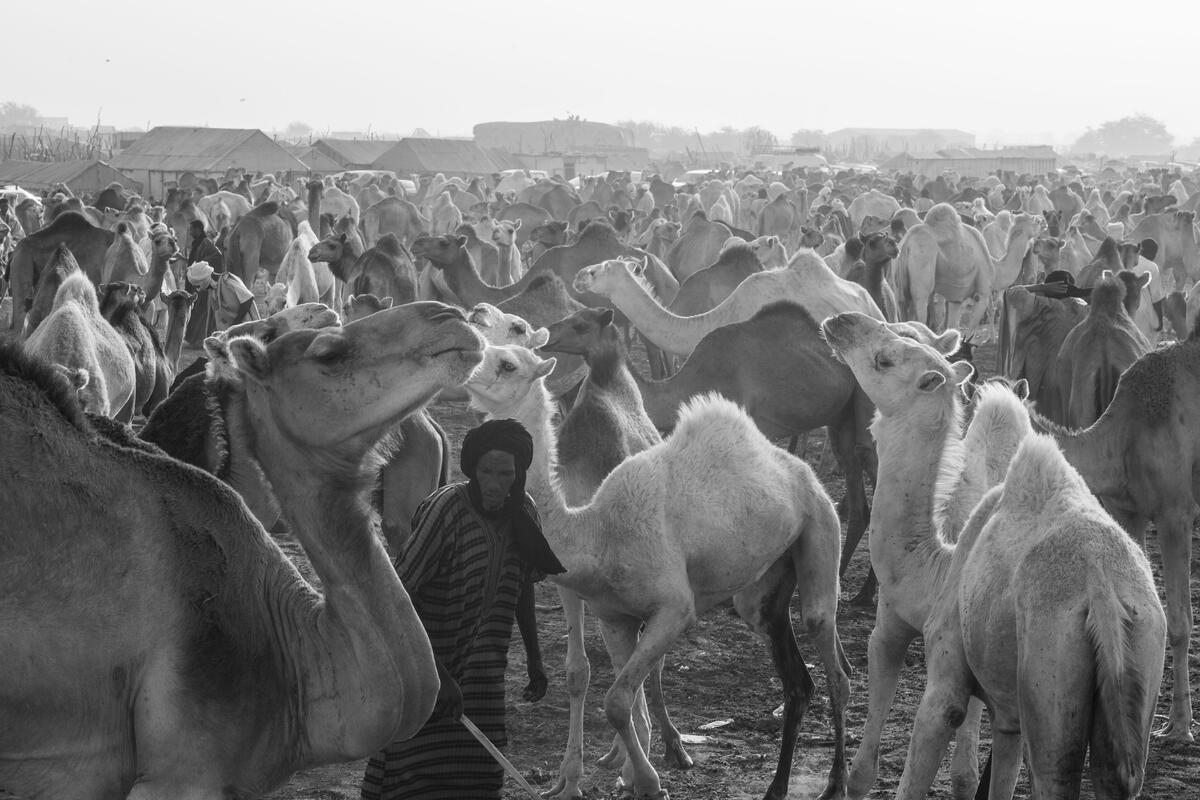

In the arid landscapes of Mauritania, where water is scarce and the deserts are vast, one animal has stood the test of time — the dromedary camel. Ten kilometers from the city center of Nouakchott, you will find the world’s second largest camel market, where around 250 dromedaries are sold on average per day. 2024 was, as declared by the United Nations, the International Year of the Camelid.

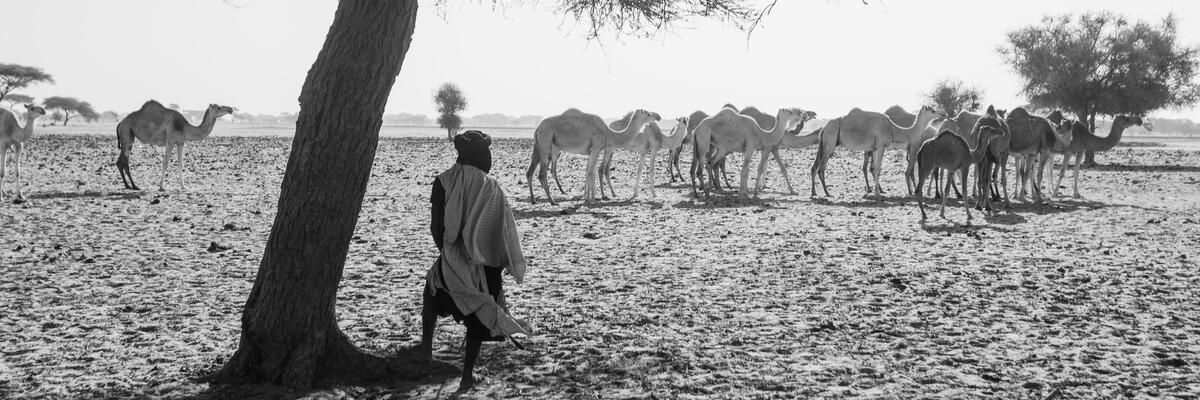

In January 2025, Tunisian photographer Zied Ben Romdane traveled to Mauritania to document the importance of camels in the daily lives of the country’s population. Working alongside the FAO, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the photographer worked in the capital, Nouakchott, then in the region of Trarza, highlighting the challenges that camels and herders face in the context of climate variability and increasing urbanization. Speaking to several individuals who are actively combating the harsh impact on the communities, his series explores how the country is adapting today.

The population of Mauritania totals around 5 million people. According to the latest census by the Mauritanian Ministry of Livestock earlier this year, it is also home to approximately 2 million dromedary camels. It is one of the 90 countries in the world where camelids live, and for the population of Mauritania, their livelihood depends heavily on their presence.

Yet the effects of climate change are proving to change the landscape of dromedary farming. “Due to drought, livestock production is under threat, leading to rising prices and a decline in supply,” Ben Romdane explains.

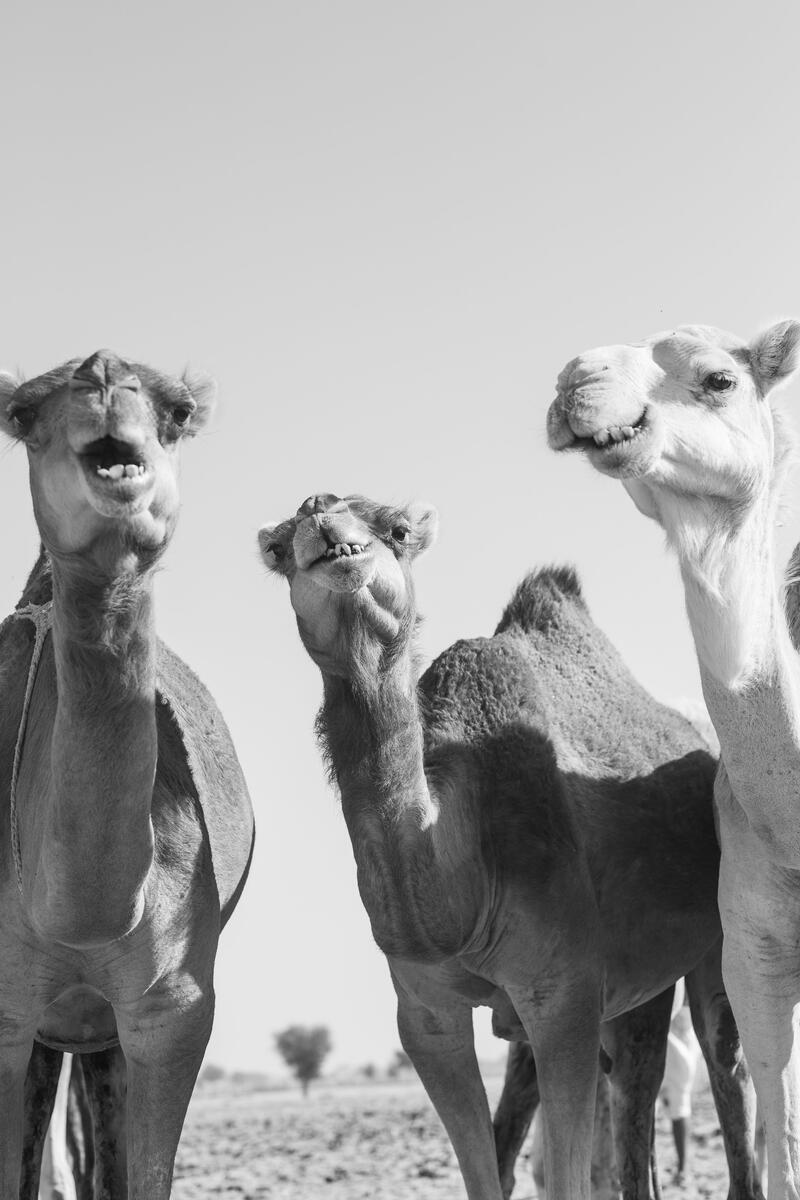

“The camel is essential to these populations, ” he continues, speaking of his work in communities in Nigeria and Mauritania. He added that the animal’s resilience to heat and water scarcity has made dromedaries an essential part of the resilience of communities in the region.

Dromedaries, as well as playing a symbolic role of strength and resilience in Mauritania’s culture and traditions, also play a vital economic role as a source of milk, meat, fibre, leather and transport. But despite the resilience that they symbolize for communities, they are not immune to the challenges of a warming planet and an increasingly dry climate.

According to a recent World Bank Economic Report, climate change-related disasters, mainly droughts and floods, have weighed heavily on Mauritania’s economic growth prospects, which has only worsened the situation for dromedary camels.

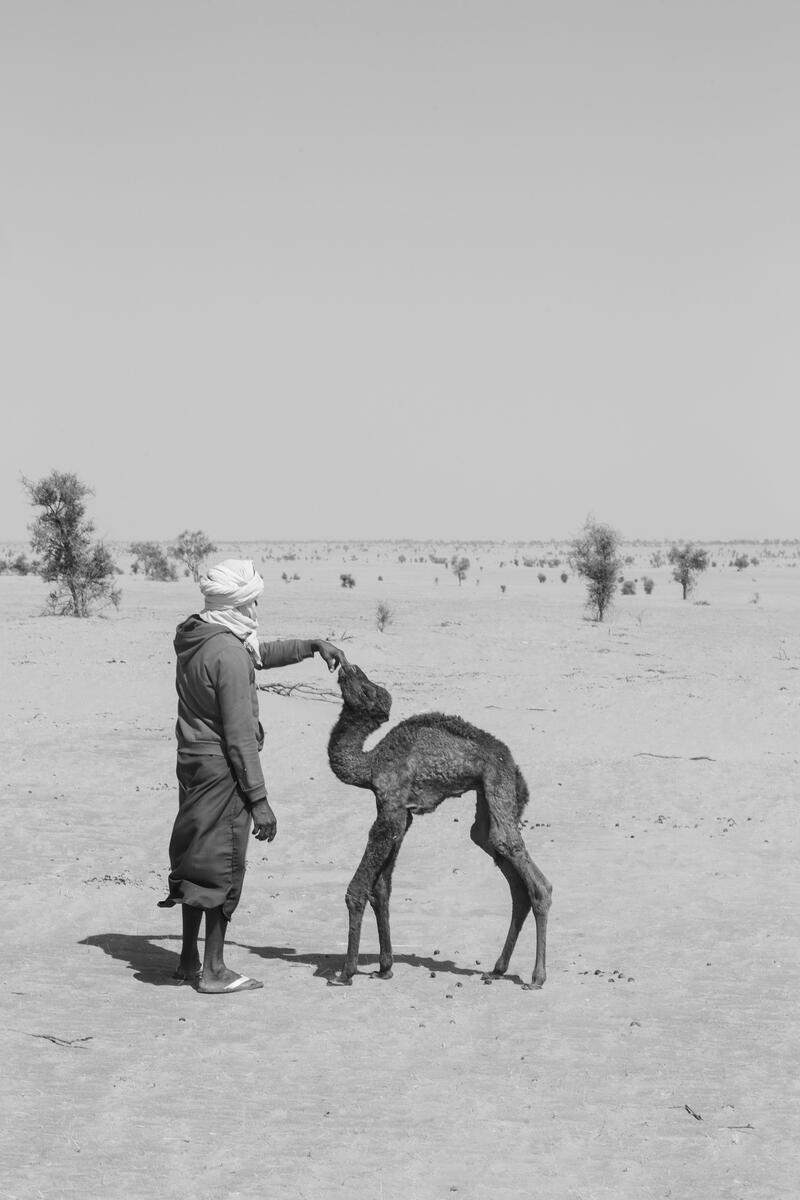

Shrinking pastures are forcing nomadic pastoralists either to travel longer distances in search of food and water, or provide supplementary feed. “The desert is advancing across Mauritania, and sometimes, the problem is such that they need to go as far as Senegal to find pastures,” Ben Romdhane explains.

In response to these environmental challenges, many traditional herders have adapted by incorporating semi-intensive farming practices, leading to the emergence of peri-urban camel farms on the outskirts of Mauritanian towns and cities, as they transition to partial or full settlement. “People raise camels in urban areas because it is logistically easier to sell the milk or the camels,” says Ben Romdane, adding that it costs less than having to cover hundreds of miles to find pastures.

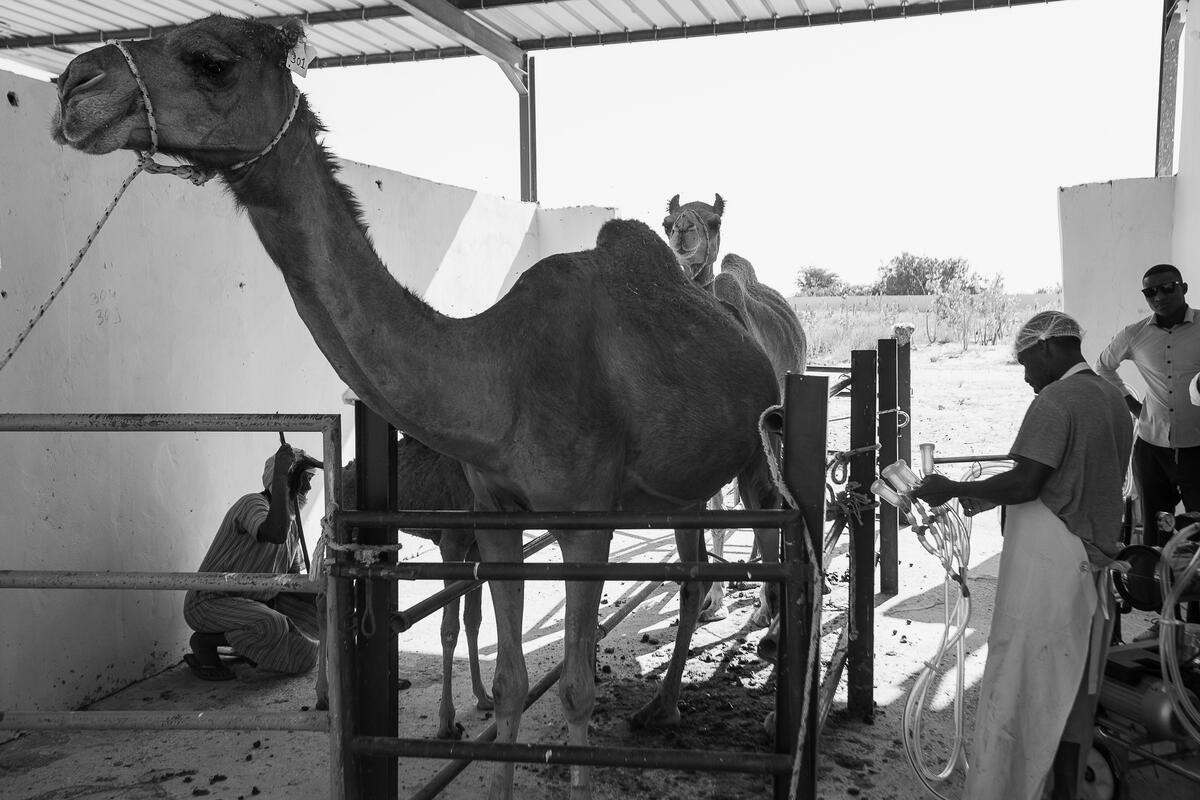

This shift has brought about the intensification of farming practices, with the use of concentrated feed for camels in these areas, the adoption of machine milking, and the rise of industrial dairies. And this has come to co-exist with transhumance, or the seasonal movement of livestock between different regions.

Camel herder Ahmed Mokhtar Salem had to borrow money from local businessmen to cover the cost of buying feed for his herd. Salem dedicated his life to camels after the death of his father and settled in Boutalhaya last year. There, he and his wife, children and mother, take care of a herd of dromedary camels, a tradition in their family for several generations. “I then sell a few camels to reimburse the feed debt,” the man in his 40s said to Ben Romdhane.

“Nomadic herders have had to adapt by finding new grazing routes, but the challenge of climate change continues to threaten their way of life. The ongoing drought has led to a decrease in camel health and productivity, making it even harder for herders to sustain their livelihoods and support their families,” writes the photographer.

Mauritanian authorities have partnered with FAO to modernize camel rearing and milk production, and industry experts say they not only benefit the country’s economy and the health of its consumers, but also support the economy in other important ways.

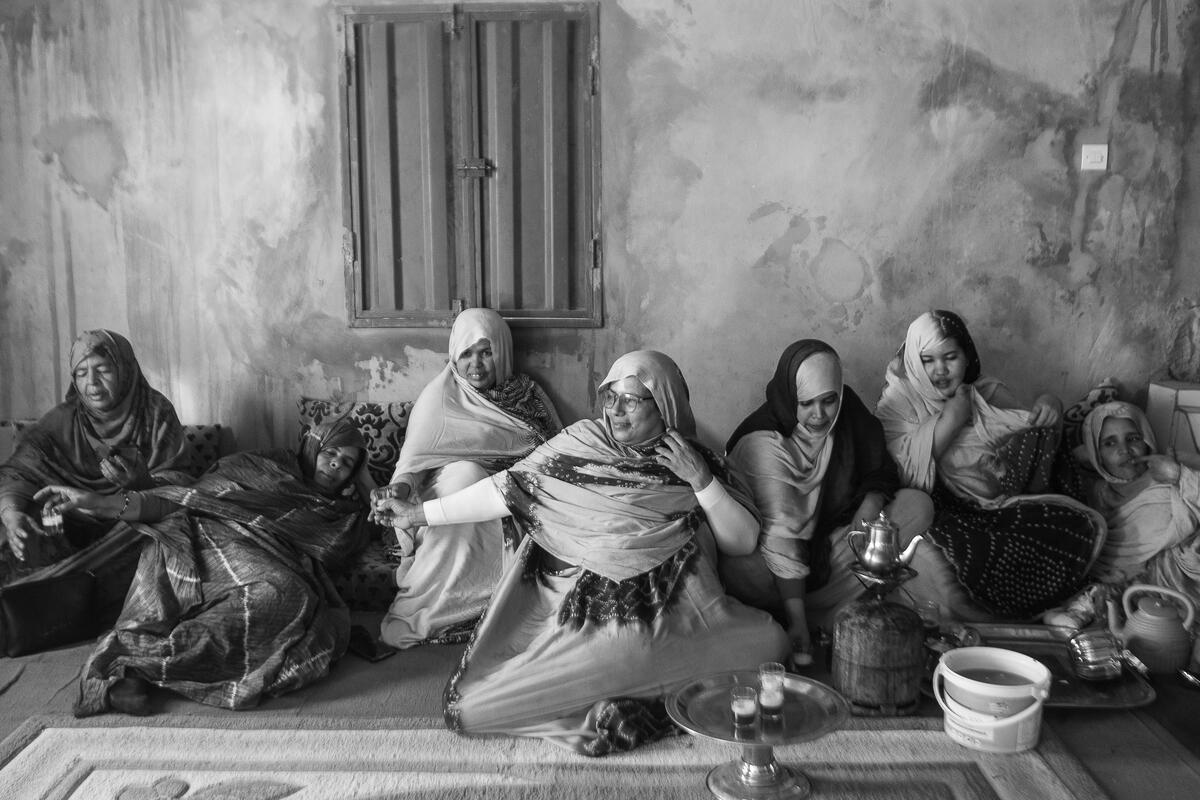

Camel milk processing has also bolstered the local economy by creating employment opportunities for rural women, explained Vatimetou Zayed Elmouslimine, head of the Teydouma Cooperative, which specializes in the collection, processing, and sale of camel milk. “Mauritanians are still heavily dependent on milk imports,” said Mohamed Salem, who is the coordinator of the Mauritanian Center for Camel Development. As a result, livestock production has moved to the forefront of research and investment.

Founded in 2016 by the Government of Mauritania and FAO, the Center aims to enhance camel productivity with a focus on milk and cheese production and reproductive biotechnologies. Given the challenges of transforming camel milk into cheese, FAO experts have trained scientists and technicians, who then transferred their knowledge to local communities. The training covered essential skills, including improved hygiene practices, as well as processing and preservation techniques.

Vivi Efeij, pictured below, is the President of the MATIS factory, a processing unit specializing in weaving products derived from sheep’s wool and camel fibre. While traveling through the desert, Efeiji witnessed local communities discarding and burying camel fibre, which sparked the idea. She proposed exchanging food for fibre, bringing it to the city to transform into rugs.

“The wool is a whole commercial system in Mauritania,” Efeiji said as she walked around MATIS’s bustling site. What began as a simple solution soon grew into a valuable activity that not only supports the local economy, but also reduces waste, showcases Mauritania’s rich textile heritage, and provides livelihoods for a sizable number of women.

As global temperatures rise, camels are becoming even more critical for ensuring food security and livelihoods in Mauritania. Protecting these vital animals and promoting their products will not only help secure community livelihoods, but also foster sustainable jobs and gender equality. For Ahmed Mokhtar Salem, Vatimetou Zayed Elmouslimine, Vivi Efeiji, and countless others like them, the camel is not just an animal — it is a lifeline connecting past traditions to the future, helping sustain communities in a rapidly changing world.

Zied Ben Romdhane has focused on issues of geography, borders, and identity in his native Tunisia and surrounding areas for more than 15 years. He has been documenting the impact of climate change in Tunisia and Canada since 2017. In an assignment for Médécins sans Frontières in 2021, Ben Romdhane worked with Tuareg communities in Nigeria to document their nomadic way of life. His debut photobook, West of Life, explores declining mining towns in Eastern Tunisia.

Ben Romdhane is one of two tutors in this year’s Magnum Summer Course, a three-week program for aspiring or practicing photographers in Marseille, France. Find out more here.