Future Proofing Life on Earth

Jonas Bendiksen photographs the Norwegian seed vault protecting the crops that could be tapped into in future ‘doomsday’ scenarios

The above image by Jonas Bendiksen is available in the Magnum Editions Poster collection, featuring contemporary works from 33 Magnum photographers. The image is available signed and unsigned in limited quantities here.

In August, scientists reported that man’s impact on the planet is so great that the era of the earth we are currently living in should be reclassified as a new age. The International Geological Congress in Cape Town recommended that this new age, which they say began in 1950, should be defined as ‘Anthropocene’, taking the place of ‘Holocene’ which began 11,500 years ago when the glaciers began to retreat. The new epoch is “defined by the radioactive elements dispersed across the planet by nuclear bomb tests, although an array of other signals, including plastic pollution, soot from power stations, concrete, and even the bones left by the global proliferation of the domestic chicken were now under consideration,” reported The Guardian newspaper.

Anthropocene is marked by man’s interferences with the planet being so great as to alter the natural course the earth would have otherwise taken. Whilst this might immediately conjure ideas around pollution and aggressive, destructive forms of farming, it also includes other of man’s interventions such as the engineering of crops and stepping in to protect biodiversity. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway exists, according to its executive director Åslaug Haga, to “safeguard one of the most important natural resources” – plants.

Rather than conceiving of a future Doomsday as a single, monolithic event, Haga reports that “there are small doomsdays happening around the world every day. Diversity is disappearing in the field and seed banks are disappearing due to war and natural disasters.” The way we farm and the way cities and industries have grown has damaged the diversity of crops, reducing options for future crops.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway acts as an insurer to other seed collections. The arrangement with depositing organizations is akin to a safety deposit scheme. The free global service allows organizations to store their seeds once they are already placed in both their own collections and another seed bank, as a final back up. They can then request to withdraw the seeds – also for free – if and when they need them. Amongst the seeds being protected this way by The Crop Trust currently are 200,000 varieties of rice and 125,000 varieties of wheat.

The diversity of crop varieties is important because it is impossible to predict future scenarios (drought, flood, temperature increases/decreases etc.) and some seeds will have the genetic features that suit those environments best. Last year saw the first ever withdrawal from the Vault, as duplicates of seeds which had been preserved in Aleppo, Syria by the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, were sent to Morocco and Lebanon from Svalbard, after the Syrian civil war had made the Aleppo bank unviable. On September 19, 2016, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) will deposit it’s 7th deposit; consisting of over 400 seed varieties, it will be their second largest ever deposit.

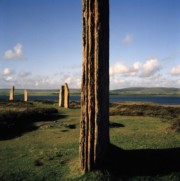

In May 2016, Magnum’s Jonas Bendiksen witnessed the deposit of more than 8,000 varieties of crops – from sheep food to chilli peppers – from Germany, Thailand, New Zealand, and the World Vegetable Center into the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which only opens 2-3 times a year. Svalbard Global Seed Vault is located on a remote Norwegian archipelago for seeds to be stored deep within the permafrost. Nestled into the rocky waste of Plataberget Mountain, amongst the snow, Svalbard is the seed bank of seed banks, designed as a back-up for others. Safely burrowed into the mountain rock, deep enough to protect it from air temperature rises and high enough to avoid potential sea level rises, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which opened in 2008, is designed to last a thousand years, and to withstand a wide range of potential doomsday scenarios, including climate change, nuclear war, and even an asteroid strike.

“If anything were to go wrong in the plant gene banks around the world the idea is that we could have the material in the seed bank in Svalbard and can retrieve it there,” explains Haga. “Ideally, we want to have a copy of each unique plant variety around the globe in Svalbard so if anything were to happen in any other seed bank around the globe we could rest assured that we can still find the variety that we’re looking for and be able to use it for natural breeding for the plant that we need.”

It’s an act of human intervention that is becoming more urgently needed as time goes on. “It is just so much more important to have access to this material now than it was in the past because human intervention is challenging biological stability,” says Haga, adding people need to understand that “we have so severely impacted our natural environment that we have got to safeguard what we have.”

A special, limited-edition collectors print featuring the Svalbard Global Seed Vault has been made available through the Magnum Shop. This story is also available as a Magnum Distribution. A new print set inspired by the traditional way photographic stories landed on the desks of photo editors, it’s a photo essay in an envelope. Profits from the sale of both the collector’s print and the ‘distro’ are shared with the Crop Trust, the charity behind the seed banks, to enable them to continue to safeguard the diversity of crops.