Saving Nature to Save Humanity

Jérôme Sessini follows an indigenous activist defending communities threatened with forced eviction from their ancestral lands

Awarded for the first time in 1988, the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought is the highest tribute paid to human rights work by the European Parliament. Each year, it gives recognition to individuals, groups, and organizations that have made an outstanding contribution to protecting freedom of thought.

To mark 30 years of the Sakharov Prize, four Magnum photographers worked with the European Parliament for a book on human rights and the people fighting for them today, as well as an exhibition that launched in December.

For the final story in the four chapters produced by Magnum photographers, Jérôme Sessini traveled to remote villages in Cambodia with Samrith Vaing, documenting the life of indigenous minorities facing forced eviction. Their way of life is under threat from aggressive and unregulated agribusiness that seems to put profit ahead of the local population.

Samrith Vaing is 35 years old and immediately introduces himself as an indigenous person. He belongs to Bunong, one of the country’s 24 ethnic groups and one of Cambodia’s most populous and oldest communities. The Bunong are thought to have lived in Mondulkiri in eastern Cambodia, near the border with Vietnam, for almost 2,000 years.

Jérôme Sessini, the photographer who spent several days with Vaing, was struck by the absolute calm of the landscapes and people. The villagers have a simplicity and authenticity they want to preserve at all costs.

“There’s nothing abstract or ideological in their make-up,” explains Sessini, who is used to the highest-pressure situations in war zones. This seems to be a calm environment. “It’s difficult to depict political violence,” he emphasizes. Sessini did, however, encounter it during their trip to Stung Treng, a province in the northeast. Vaing wanted to visit villages in the forest, but the police and military barred access to them. Any contact with the local communities was therefore impossible.

But the human rights activist was determined to get past the blockade — no matter the cost. He wanted to convey to his visitor the difficulties faced by these communities, left at the mercy of Chinese companies gobbling up their land with the complicity of the government. Sessini stopped him from taking such a risk; the dangers were too great.

"If they’re not aware of their rights, how can they defend themselves?"

- Samrith Vaing

The stakes are clear. Here, the defense of individual freedoms cannot be separated from that of the environment, the forest and its inhabitants — people and animals —like the monkeys who share the peoples’ lives or the dogs that appear in photographs as a part of the family.

When the photographer arrived in Cambodia, Vaing was happy to be able to speak English for an entire week. This was an opportunity to improve his command of the language and fine-tune the message he wants to send to the international authorities and the people whom he wishes to make aware of his cause. The link between people and their land, the conservation of natural environments and the fight against climate change is at the heart of his concerns. “I go to the ground,” the activist often says—his way of showing how closely involved he is with the people and their worries.

“I’m particularly interested in the forest,” he says. “I expected the government to act and stand by our side in our efforts. But it hasn’t done anything. Quite the opposite, in fact: the forest has disappeared. Some activists have even been killed or are currently in prison. Others finally succumbed to the pressure exerted upon them and gave up.” Vaing, however, refuses to let himself be intimidated. He wants to fight for his people against all injustice, without leaving anyone behind. Saving nature to save humanity.

Seeing this country and the forest people persuaded Sessini to eschew color. He believed the lives the people led needed to be captured in black and white. “To get to what matters,” he said, “it’s best to convey beauty while removing everything that seems superfluous from the frame.” As if he were seeking to establish a more direct relationship between the subject and the beholder.

What struck him most in this country still haunted by the ghosts of the genocide carried out by the Khmer Rouge from 1975 to 1979? At the Museum of Memory in Phnom Penh, Sessini saw thousands of photographs of victims, their faces forever silent yet saying so much.

Some of the severity of their expressions find echoes in his pictures, such as the photo of the open-air market in Stung Treng, where a determined young woman sells her home-grown vegetables in the rain. Here the indigenous people have been living under the constant threat of expulsion since a Chinese company began building a dam. To force them from their homes, the local authorities ban the Bunong from using the covered markets, which are, nevertheless, still standing. By leaving them exposed to the elements, the authorities are trying to weaken their resolve. They also know that by imposing these precarious conditions, they are making it more difficult for them to earn their income. This is how they hope to convince the Bunong to accept the central government’s offer: to leave their homes and resettle far from their ancestral lands, in anonymous dwellings in places without history.

These relocation programs are terrifying for the Bunong forest people, who only ask to be allowed to remain on the land where they have always lived. Vaing stands alongside them. He knows that the powerful are untroubled by questions of conscience. The country’s ruling clan can raze thousands of hectares without raising an eyebrow and without worrying whether there are villages there or not. Financial interests trump all other concerns.

This is where Vaing comes in, via his organization called Community Development Cambodia. “I worked in a national association based in the capital for a long time,” he explains. “We didn’t have much funding, so money for travel was tight. Now I’m back in my home province, Kratie, a popular tourist destination. We have all kinds of difficulties here. The local indigenous people have been overcome by an invasion of sugar cane plantations. Chinese and Vietnamese companies take over land, cut down the forest and plant sugar cane. Elsewhere the problem is rubber plantations. Near the border with Vietnam it’s palm oil farms, something that puts people’s lives in danger and cuts off access to natural resources.”

These serious imbalances are a result of the government’s policy of granting permits to foreign companies in exchange for cash, thus allowing land to fall into the hands of unscrupulous investors. Corruption prevails and the forest is rapidly disappearing. “The companies that set up facilities here produce fake reports claiming that their activities don’t affect the people. The authorities turn a blind eye. Foreign companies quickly clear vast tracts of land. The timber is sent to Vietnam, and then to China for sale.”

Sessini’s photographs speak for themselves: a long succession of desolated, devastated landscapes, as if hit by an earthquake. Deforested land shorn of its vegetation becomes unstable; floods cause untold damage. Only children enjoy them, diving into these temporary seas that swell up out of nowhere.

Vaing offers people threatened with being driven from their homes a powerful weapon: knowledge of their rights. “If they’re not aware of their rights, how can they defend themselves?” Despite the risks, he does not hesitate to speak in the media when necessary or to give his name in public. He uses social networks and releases many videos. He has even set up his own YouTube channel to inform people of his actions.

"If these vital issues are not solved together, bitter conflicts will break out"

- Samrith Vaing

His work remains altruistic: “I keep out of the spotlight so as to help indigenous people. I am behind them to help them build their defense. My aim is to raise awareness, not to fight against any particular organization. I avoid pointing the finger at the government. My strategy is not to criticize directly but to highlight acts of wrongdoing. Another focus of my work is global warming, which is closely linked to the issue of living conditions. This was something I learned from observing the situation in Malaysia. The native people live off the bounty offered by the forest: honey and game. They also extract resin and rubber, and in return they take care of the forest. Their protection of the forest acts as a brake on climate change. Here in Cambodia, indigenous people are fighting to ensure that the government takes action and safeguards not only their rights of access to land and natural resources, but also their right to have schools, roads and hospitals. If these vital issues are not solved together, bitter conflicts will break out.”

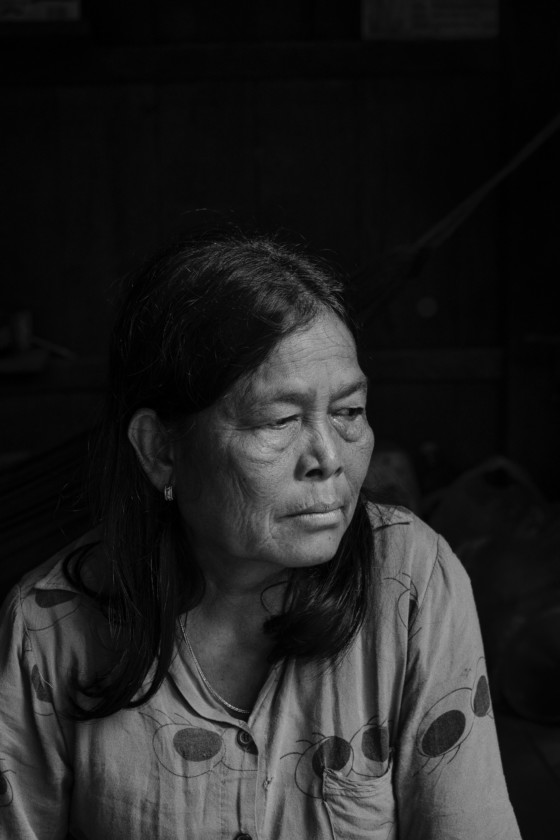

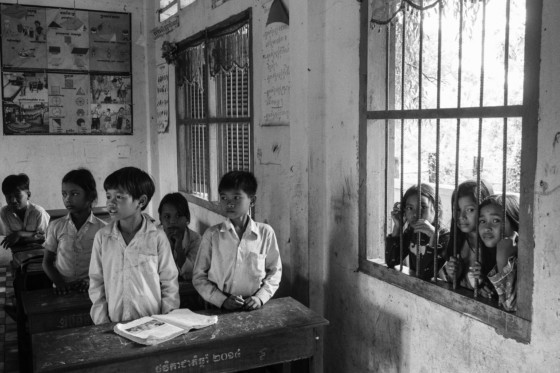

In his unrelenting work helping the families he meets to fight for their rights, Vaing passes on his fire, energy and willpower. The expressions captured by Sessini radiate a quiet determination, a mixture of serenity and firmness that deeply struck the photographer. The face of a woman in front of the Chinese Rui Feng industrial complex, which is suspected of an illegal land grab of 500 hectares to plant sugar cane in Preah Vihear province; the faces of Kui villagers in the village of Prame — women, children, fishermen and schoolchildren who simply want their lives to remain the same. Observing them is a lesson in courage and a source of hope.

See the stories from this series here.