Photographing Australia’s Black Summer

Paolo Pellegrin travelled to Australia to document the aftermath of the catastrophic bushfires that swept the country

Paolo Pellegrin’s photo series exploring the Australian bushfires documented the disaster that swept the country during the disastrously hot and dry bushfire season of 2019 to 2020, also known as the Black Summer.

As Australia recovers from another season of fires, writer and curator Annette Liu reflects on Pellegrin’s work from the time, comparing the intensity of images which saturated media of that period with the more somber scenes of devastation present in Pellegrin’s work.

It’s been over a year since the bushfires of Black Summer devastated Australia. The severity of the fire was unprecedented, with over 10 million hectares of land burnt across the country, an estimated 3 billion animals killed or displaced, over 3,000 homes destroyed, and 33 civilian deaths – twenty five of them in the state of New South Wales that killed nine volunteer firefighters and three American aircrew. The 2019–2020 bushfire season was the worst the state had ever recorded.

The first warning of the bushfires came early in June 2019, and its staggering destruction unfolded quickly in the eight-month period that followed. I remember feeling bewildered and anxious in the hazy air, and peering in awe at the scorching, red sun. Heavy smoke blanketed Sydney in December, and the smell of it crept into homes, offices and trains. There was panic around the severity of air pollution as masks were selling out in Sydney, and the government worked to provide them to affected communities. Horrifying images of the devastation by the fires circulated immediately across news outlets and occupied social media. Photography made it possible to communicate the calamity of the bushfires at their peak. Donations poured in as photos, infographics, and maps of the disaster’s impact went viral and were shared by high-profile celebrities internationally. Although some of the content was misleading at times —maps circulated virally exaggerated the area of the country that was burning — the mass circulation of images provoked a national debate about climate change as it elicited public anger for the Prime Minister and his government’s inaction on the climate crisis. There was great solidarity in this, with climate change rallies that saw tens of thousands of students protesting, and an open letter signed by more than 400 international scientists calling on the government to commit to science-informed policies to combat human-caused climate change.

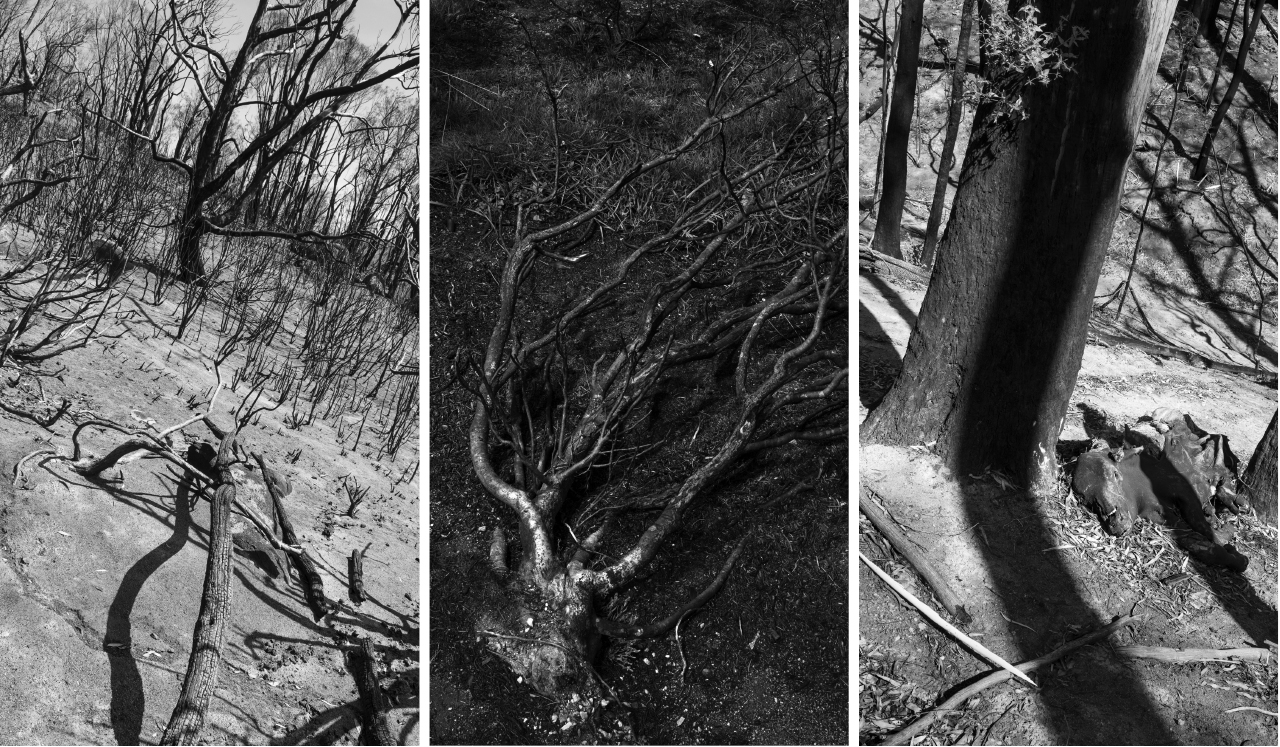

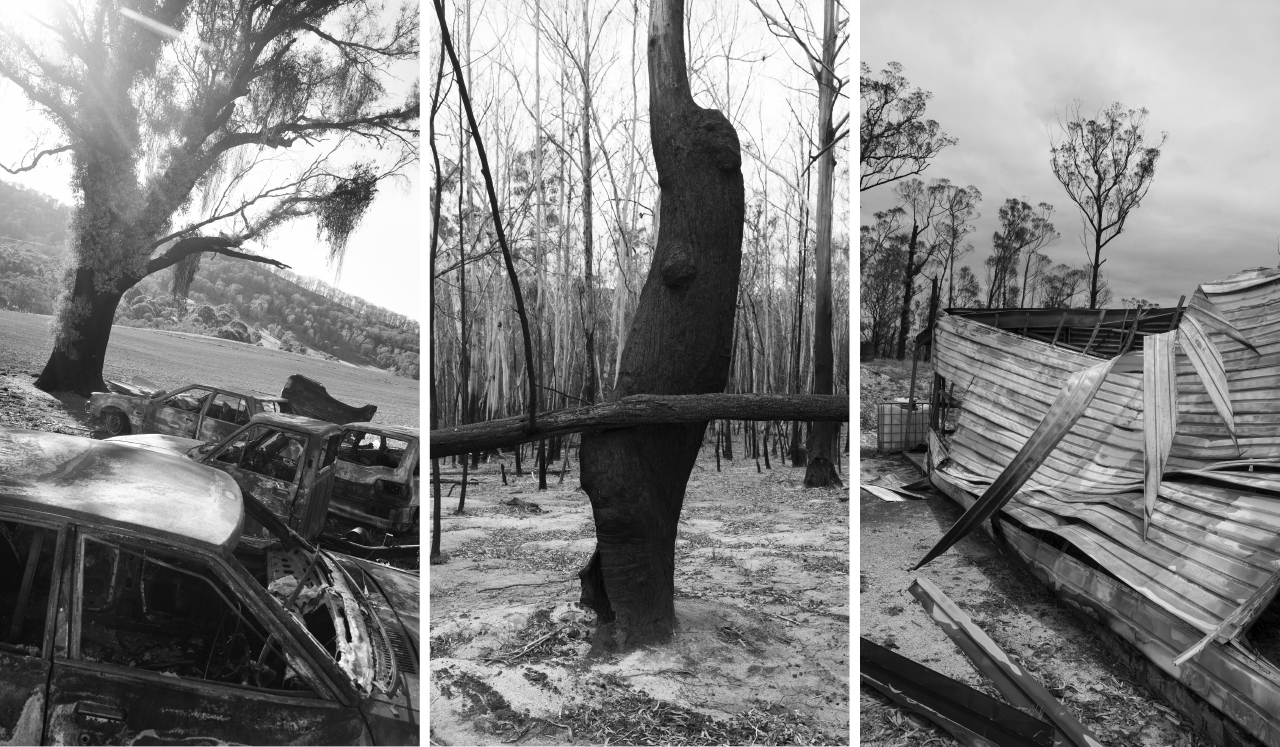

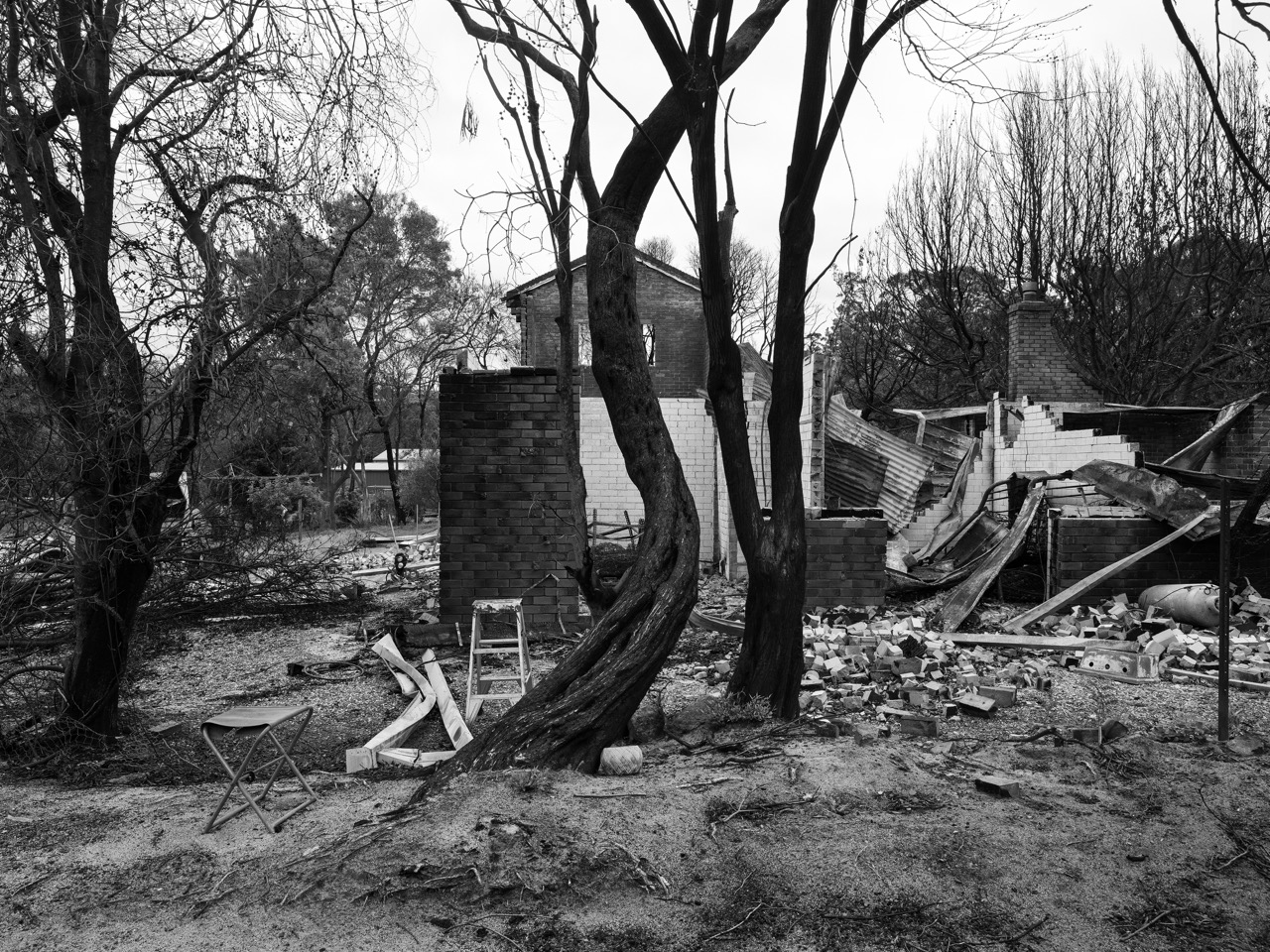

Magnum photographer Paolo Pellegrin purposely flew to Australia towards the end of the fires in mid-February of 2020 to document the environmental consequences. A somber testimony to the crisis, Pellegrin’s black and white images stand in stark contrast to the saturated reds and oranges in the images that were disseminated across media. Pellegrin had seen the existing reportage and wanted to take an alternate angle. “I wanted to show what it looks like after what is left after the fires have swept the land,” he says. His photos of burnt cars, dead horses, and destroyed homes are particularly grave as some of the exposed remains are left almost indistinguishable. The lack of colour in these images quite literally highlight the loss of life, solidifying the no-longer. Pellegrin’s documentation shows no people, but these images of destroyed property allude to the countless personal tragedies and communal losses. “This was the best way for me to tell this particular story,” he says. “It was this absence that I sought to capture in these images. For decades I had been aspiring to make additive compositions—complexities, layers, textures. But in this case, I needed to subtract. The landscape, all on its own, told a very powerful story – possibly even alluding to the future, should we continue on this path of environmental destruction. Carbon, blackness, melting, death—the aftermath of one fire, the shape of those to come.”

Pellegrin’s documentation in Australia continues his environmentally focused projects and underscores his preoccupation with the consequences of global warming. In 2017, he joined NASA’s IceBridge expedition to document the impact of climate change in Antarctica. The images are abstract and beautiful, but highlight the region’s unsettling fragility that the scientists at NASA were studying. Similarly, his new body of work provides a poignant visual context for the ongoing research on the role of climate change in Australia’s Black Summer.

As a leading photojournalist who has documented this generation’s major disasters, Pellegrin understands that destruction can rarely be comprehended by statistics alone. His images of the burnt trees and bush lands in NSW’s Kosciuszko National Park are graphic and haunting as they reveal the massive scale of the fire’s damage. The bleak landscapes in his photographs of burnt pine plantations at Bondi state forest are shocking in their depiction of the ecological disruption left by the fires. Pellegrin has experienced the spectrum of challenges of depicting climate change visually. “Some events have a beginning and an end that can be documented – like storms, floods and fires,” he says, “But the bigger and longer processes, like melting ice caps, pose a great challenge to photography. We’re living it now, and although scientists can model the outcomes, it is a challenge to document the transformation.” Pellegrin’s images are nevertheless an emblematic reminder of photography’s forceful role in advocating for environmental causes.

Extensive research conducted by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes and the NSW Bushfire Risk Management Research Hub described the bushfires as an urgent wake-up call, indicating that the disasters were made worse by human-caused climate change like severe droughts that escalated the fires and created firestorms. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)-led research estimated that more than 100 Australian plant species had their entire populations burned, and that while some species have adapted to recover from fire, other ecosystems were now at risk of regeneration failure. Despite these damages and challenges, the country’s landscape has been slowly recovering since March 2020. Epicormic growth – the sprouting of dormant buds triggered by fire – has been documented in New South Wales and evidence of rebounding populations have been found along eastern Australia. Pellegrin’s image of a delicate fern group signifies this resilience in the ecosystem. It’s the most tender image in his series, yet demands great attention with its gentle focus on each fern and every frond. The signs of destruction are minimal here. Taken in Mallacoota, VIC, where one of the worst fires took place, it’s at once an image of hope and a reminder of the precarious state that we live in if we continue to deny the impacts and devastating consequences of human activity on climate change.