Four Tumultuous Decades in Afghanistan

10 Magnum photographers reflect on their experiences depicting violence and beauty in the country from 1978 onwards

Reflecting upon the anguish, turmoil and death that preceded the final day of the U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan, here we compile over four decades of coverage from 10 photographers — from 1978 to the present.

The work of Magnum’s collective builds a mosaic of portraits of the country, bringing together views from Raymond Depardon, Steve McCurry, Abbas, Chris Steele-Perkins, Alex Majoli, Thomas Dworzak, Jerome Sessini, Moises Saman, Larry Towell, and Peter van Agtmael. These bodies of work provide context and understanding spanning 1978 to the present day covering Afghanistan.

1978: Raymond Depardon

The dramatic struggle of the Afghan people has been captured through the lens of Magnum dating back to co-founder George Rodger’s documentation of the country’s role in WWII. Ever since then, Magnum’s intrepid photographers have crisscrossed the country’s striking landscape making photographs.

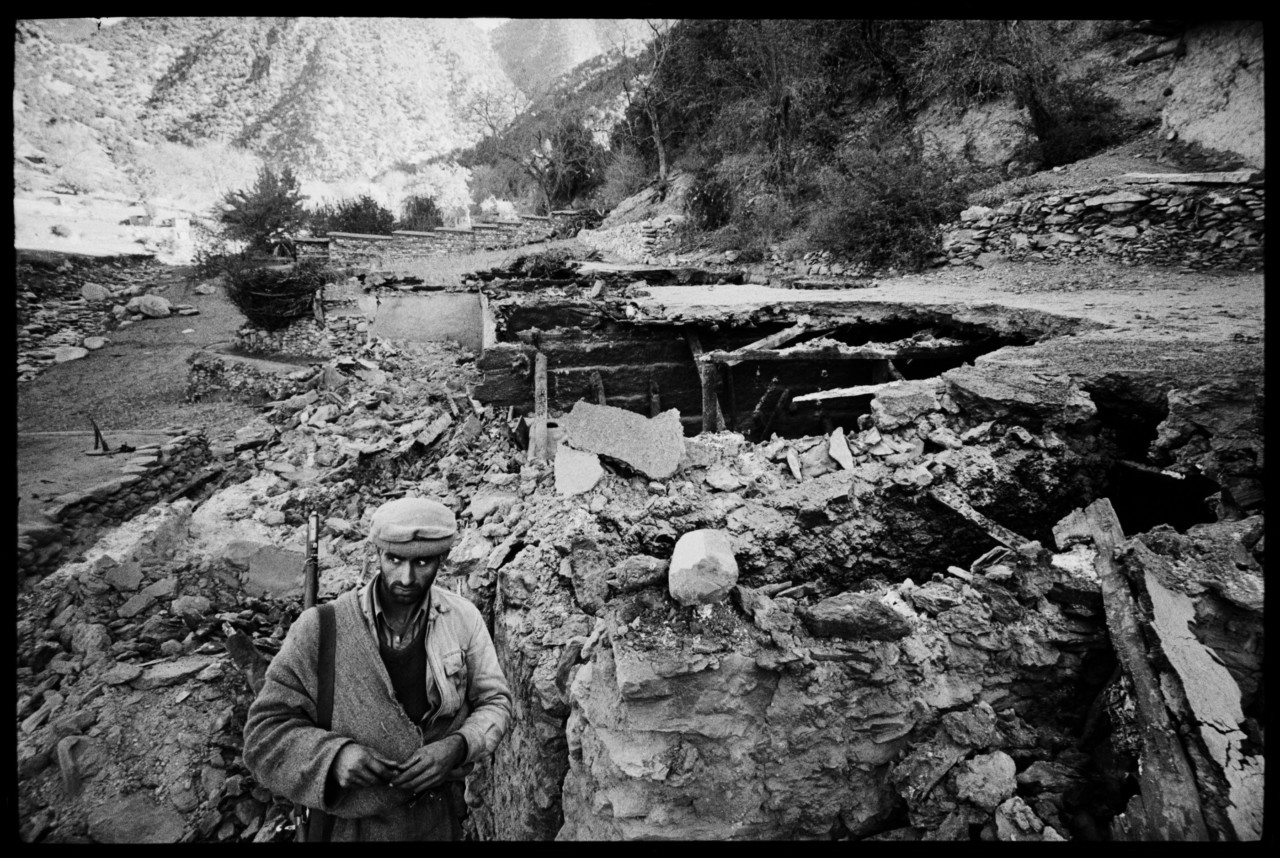

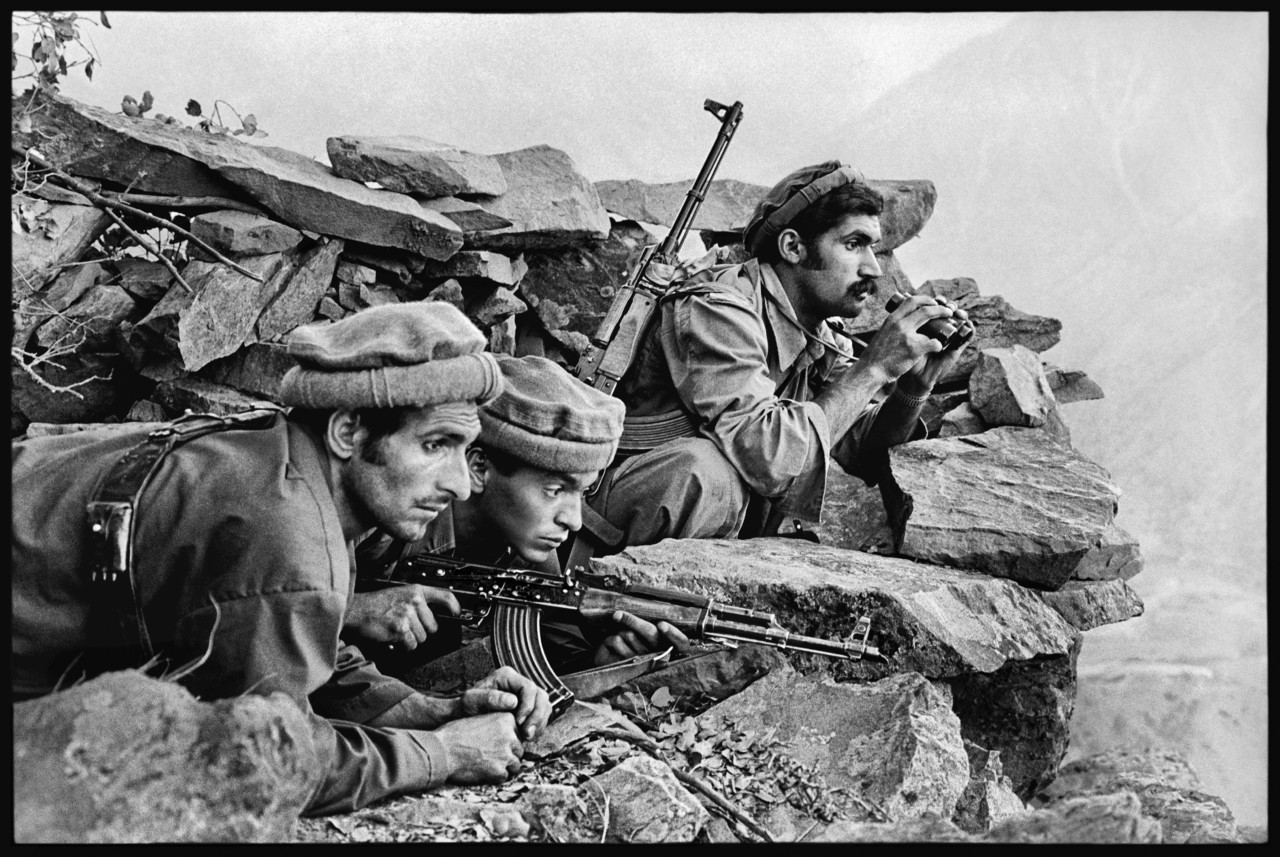

The ultimate overthrow of the monarchy and brutal liquidation of Afghanistan’s constitutional government in 1978 heralded the arrival of Soviet-style communism. Those living in Nuristan Province rebelled immediately with a jihad or holy war, covered first by Raymond Depardon within Magnum. It was in 1978 that Depardon met the anti-communist Afghan rebels in Peshawar, Pakistan. The rebels offered him a clandestine visit to their Afghanistan camp and provided a French-speaking guide.

His guide?

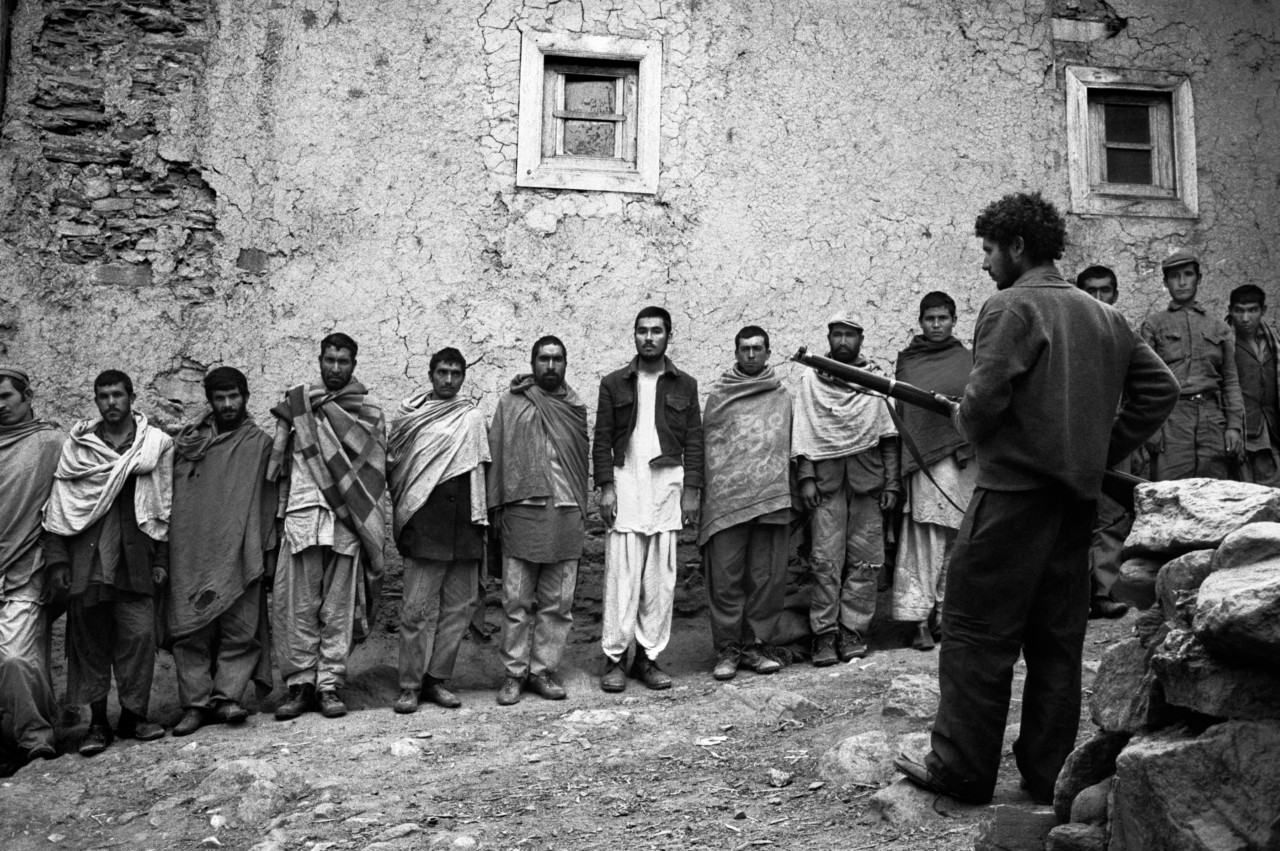

“Ahmad Shah Massoud accompanied me throughout my trip to Nuristan. I didn’t know he was going to become Commander Massoud of the Panjshir Valley,” Depardon said. “It was an incredible trip because he explained to me every event we encountered – prisoners, local customs.”

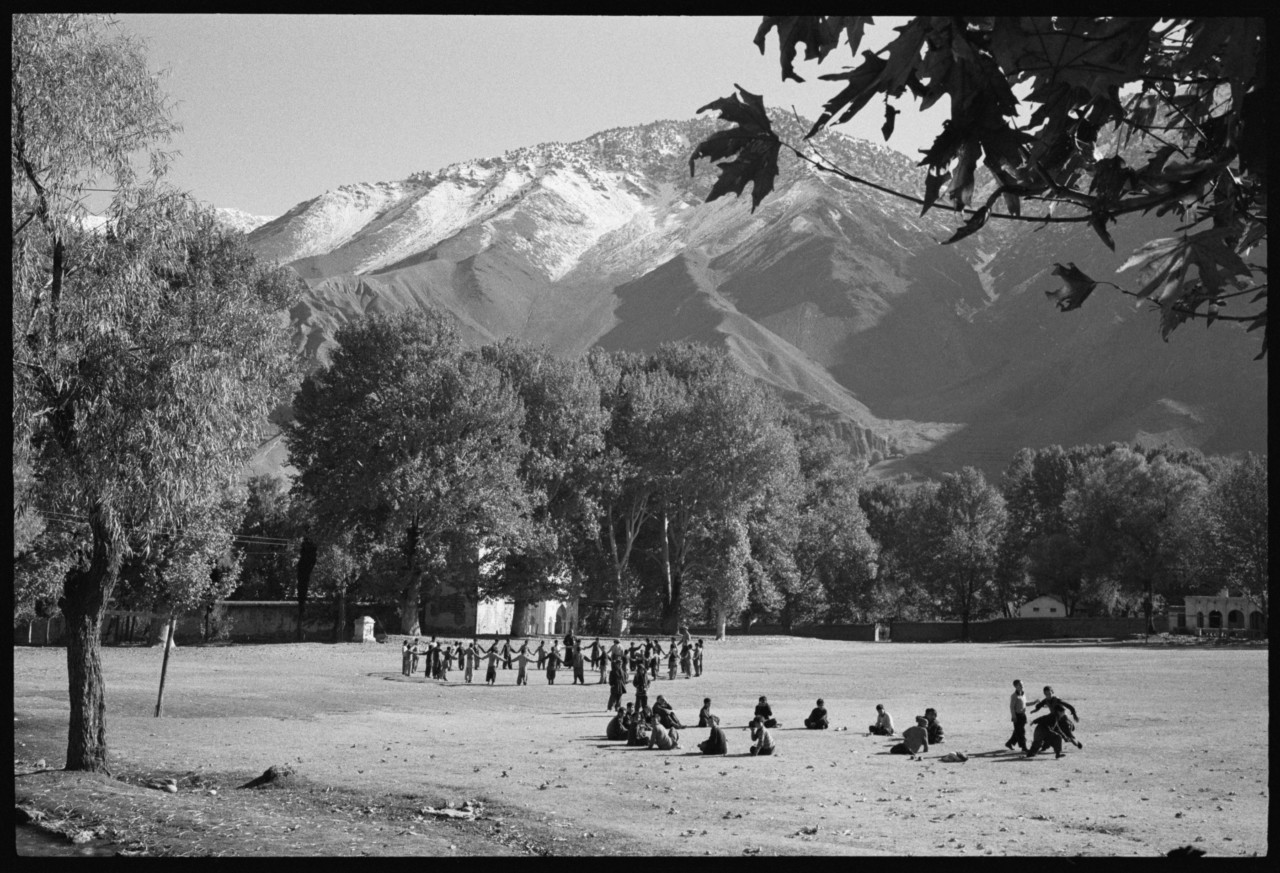

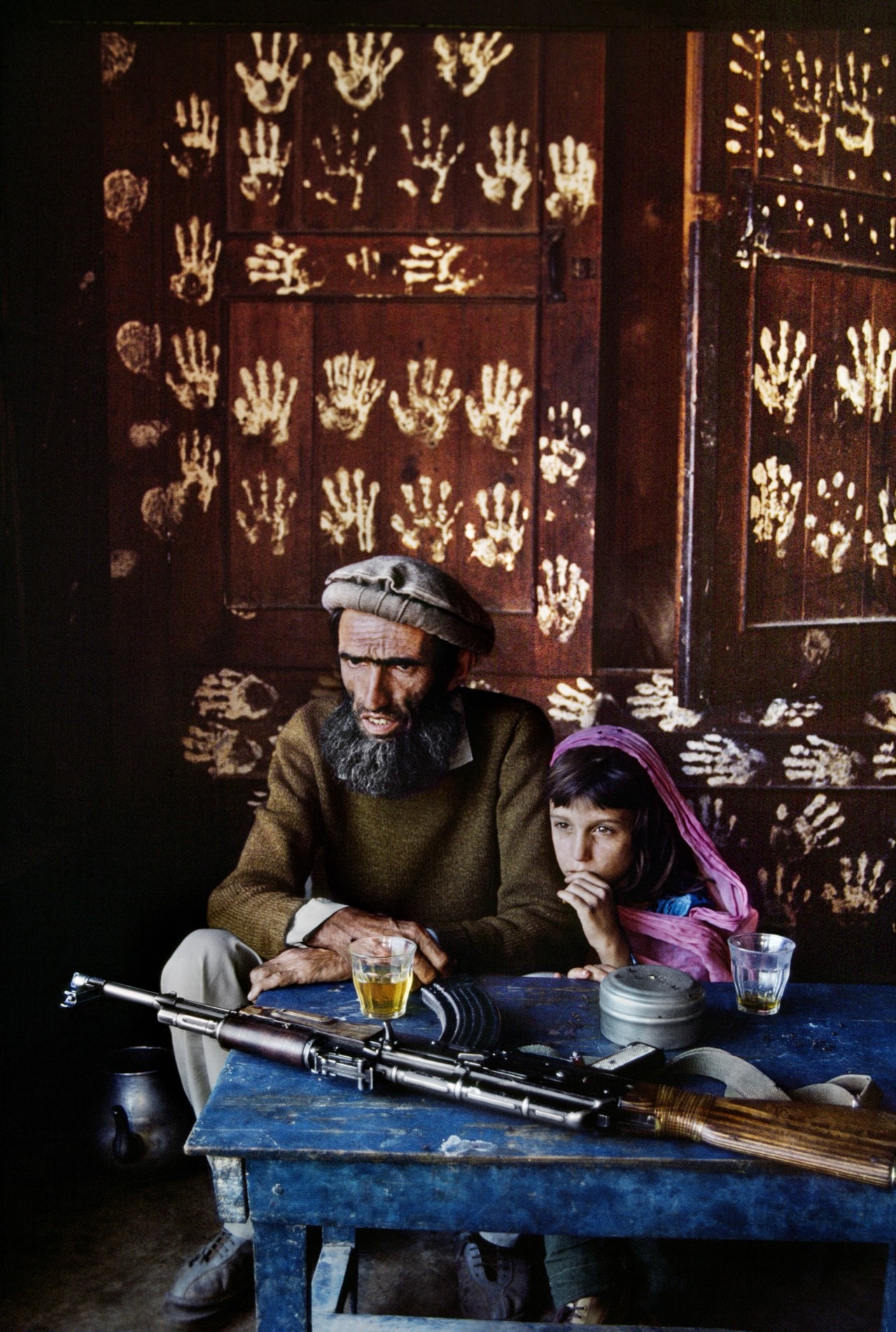

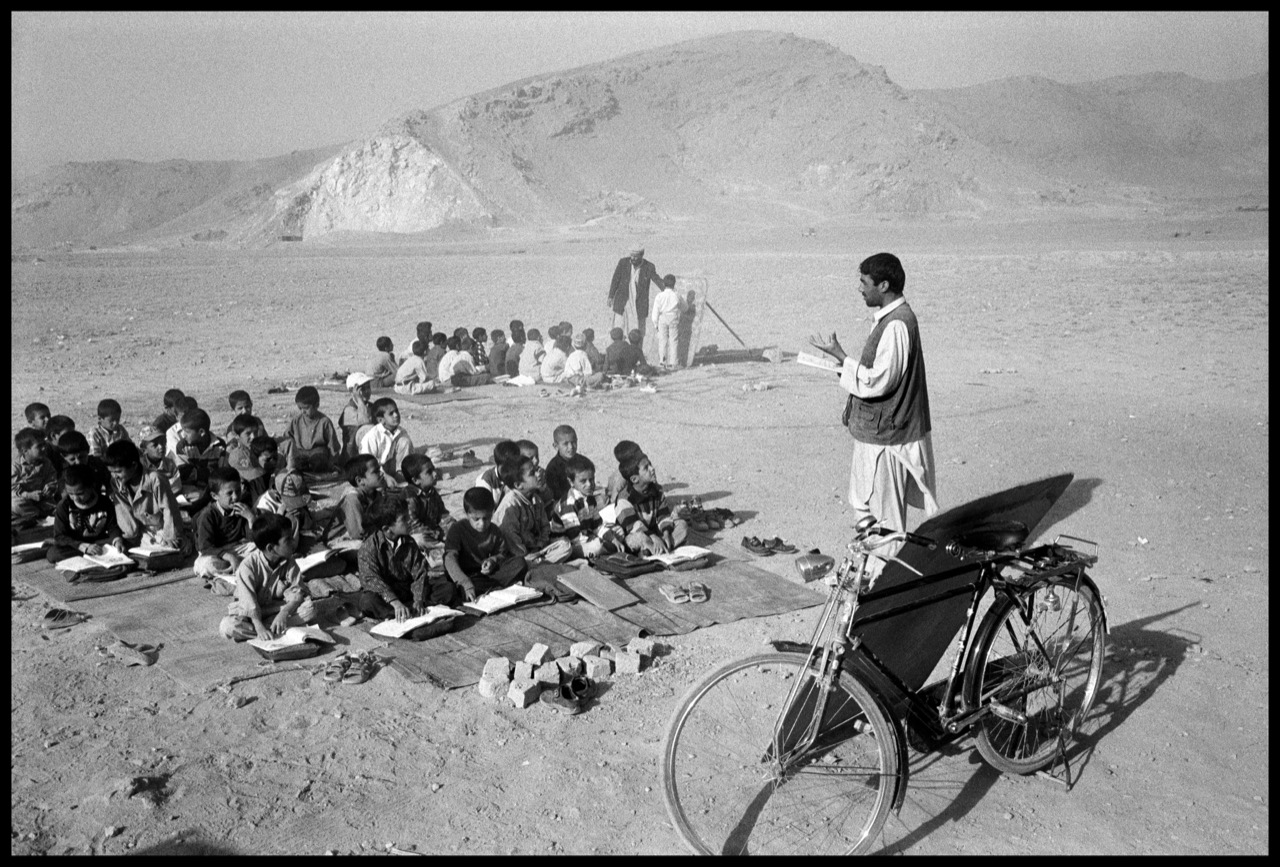

1979–2016: Steve McCurry

For Steve McCurry, Afghanistan has elicited special memories since his first visit 42 years ago. He arrived mere months before the Soviet invasion and reflected on what he experienced.

“After working at a newspaper in Philadelphia, I left to do magazine freelance assignments in India in 1978. I spent one and a half years traveling throughout India and Nepal and photographed for a variety of small magazines.”

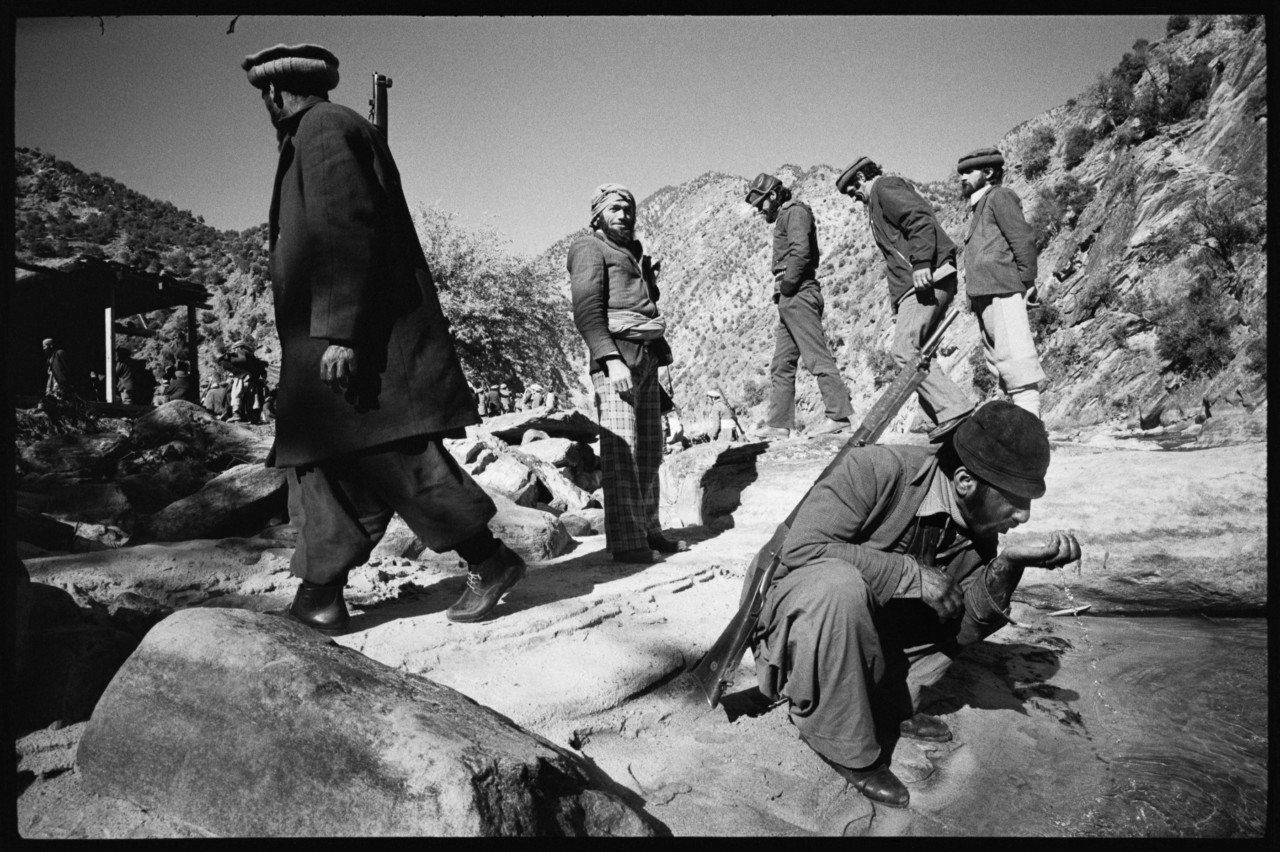

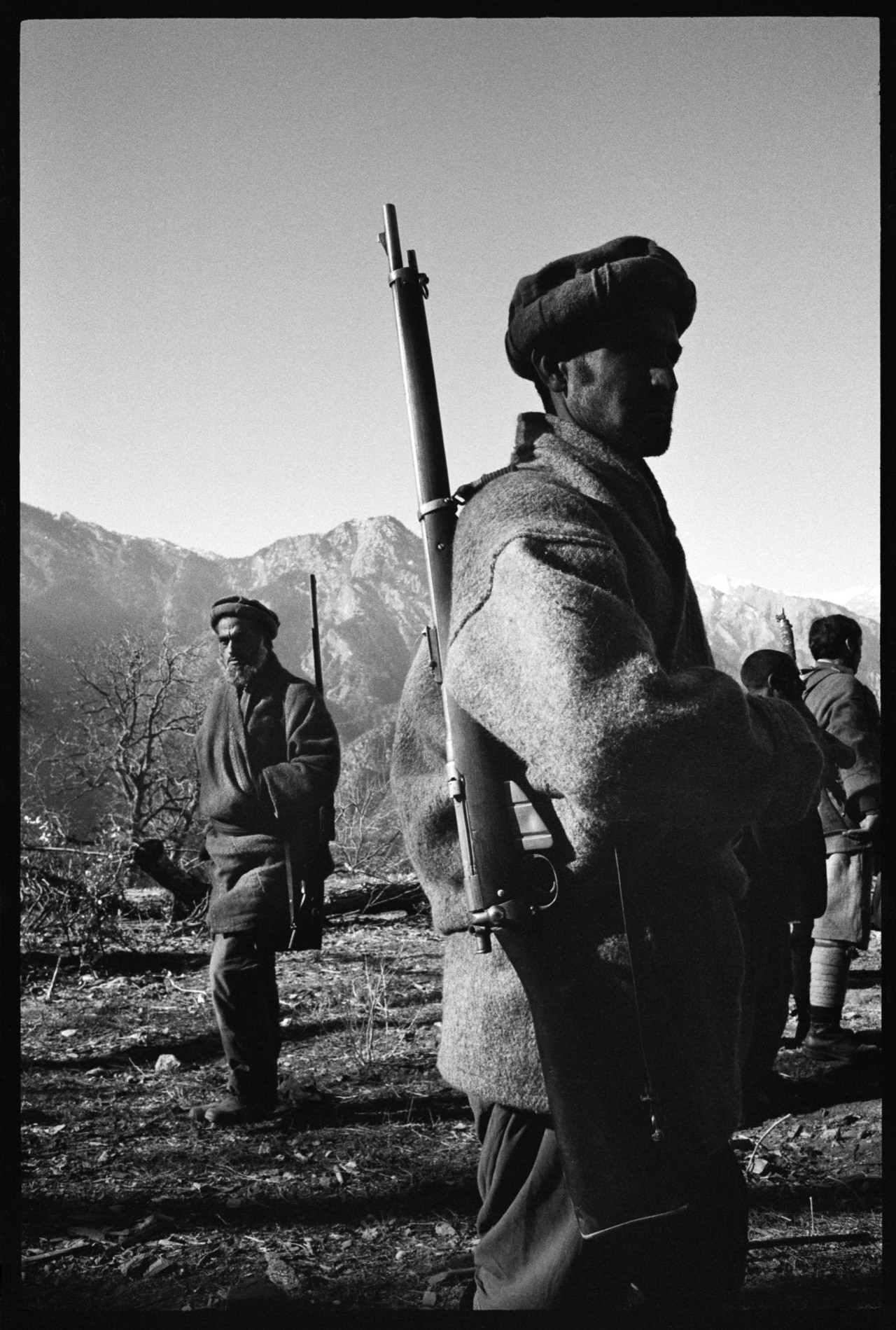

“In the spring of 1979, when the temperature was more than 40°C, I traveled into the mountains of northwest Pakistan to explore the part of the subcontinent that I had not visited before. While staying in a small hotel in the village of Chitral, I met some Afghan refugees from Nuristan, who explained that many of the villages in their area had been destroyed by the Afghan army. I told them I was a photographer and they insisted that I come and photograph the civil war that was raging. I never photographed in an area of conflict and wasn’t sure how I would react.”“After a few days, I walked with them over the mountains into Afghanistan and spent nearly three weeks photographing life there. I was astonished to see so many villages that had been virtually destroyed with no inhabitants left to tell the tale. The roads were all blocked or under government control, so we had to walk everywhere. I met some people with whom I became very close. I was also very affected by the culture and the beauty of the country. It was a different way of life, with no modern conveniences, and I was drawn to the simplicity of the lifestyle; everything was reduced to basics. It has drawn me back time and time again.”

“I was continually under fire as I documented mujahedeen fighters and the streams of people fleeing from their villages. The human drama in such areas can be difficult to comprehend. I think documenting these dire situations and giving a voice to the people who aren’t able to tell their stories is what photography does best. Although I often work in areas rife with conflict, the images I make are about the people themselves. For me, the goal is to find some sort of universality among peoples.”

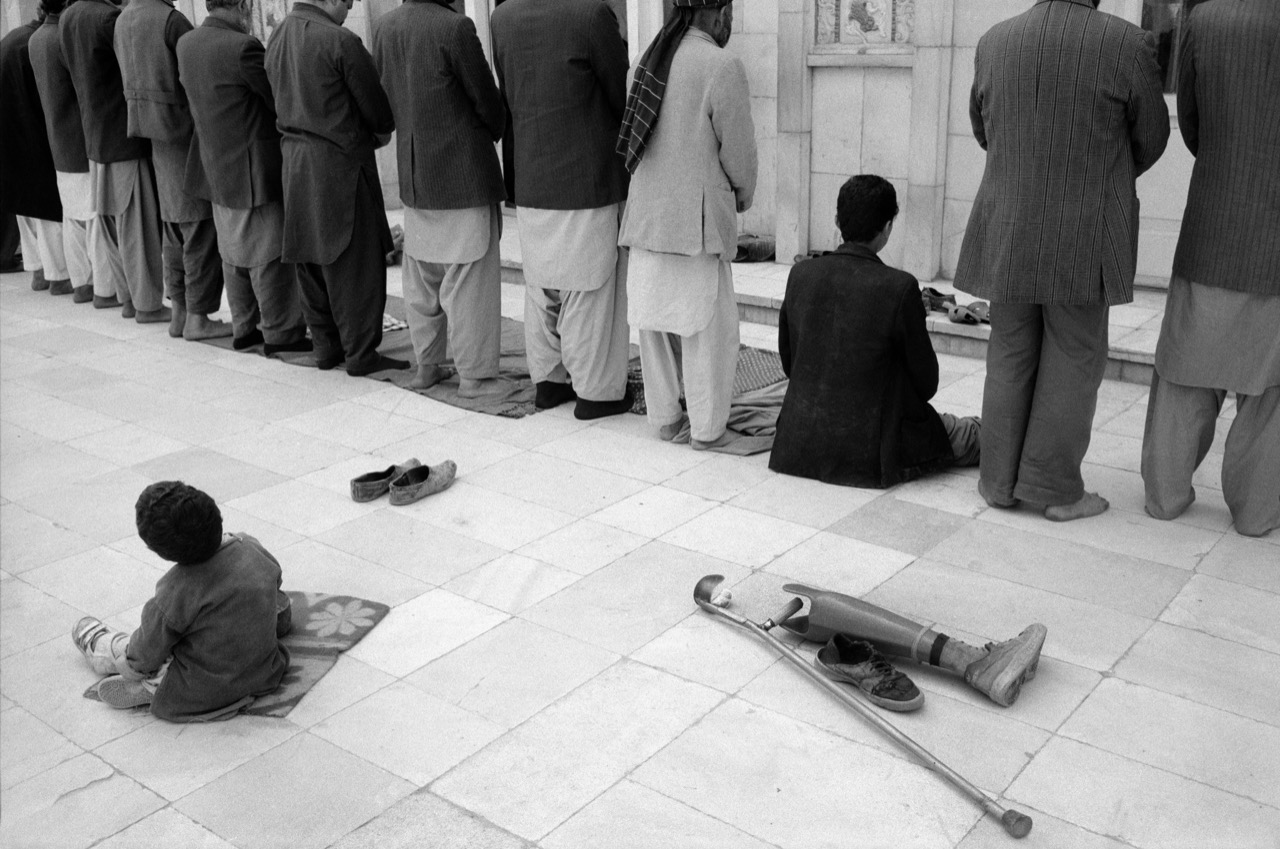

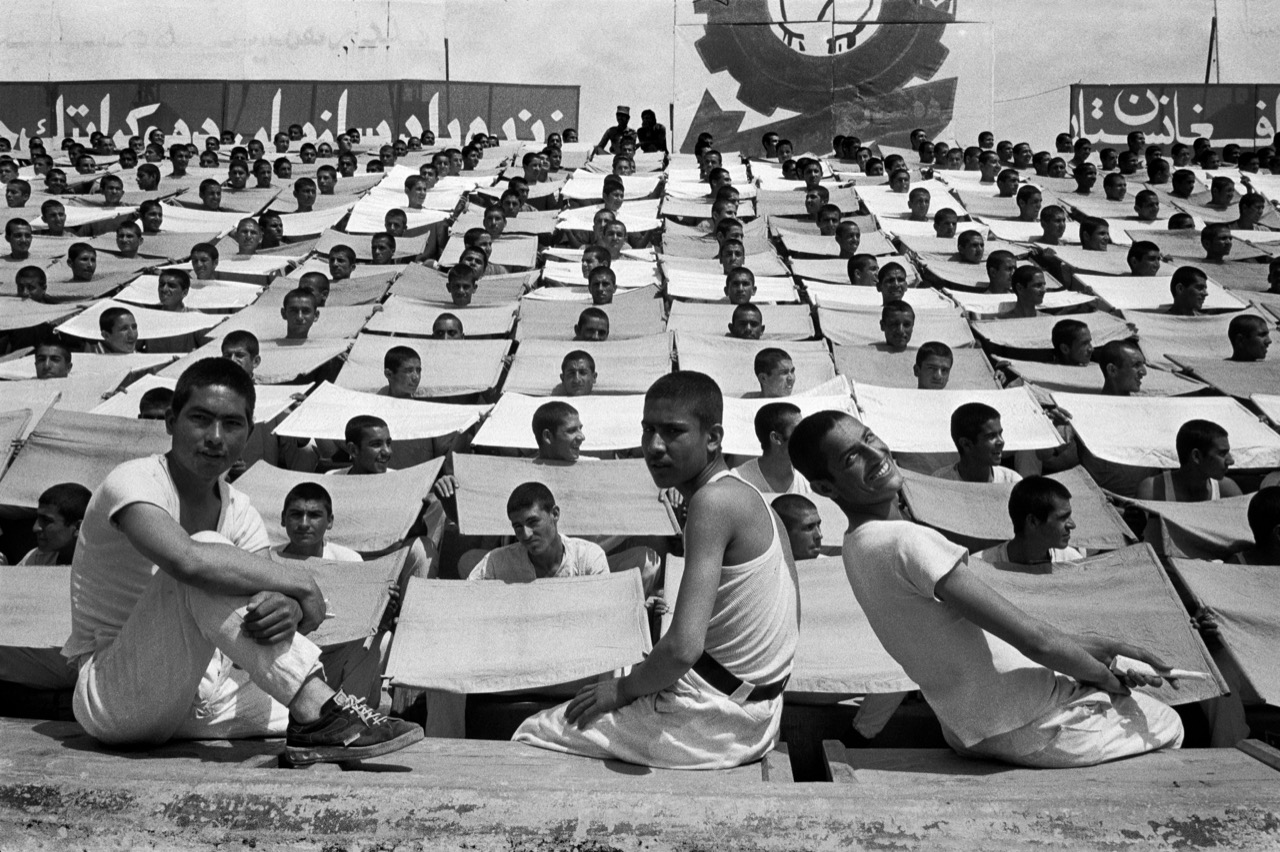

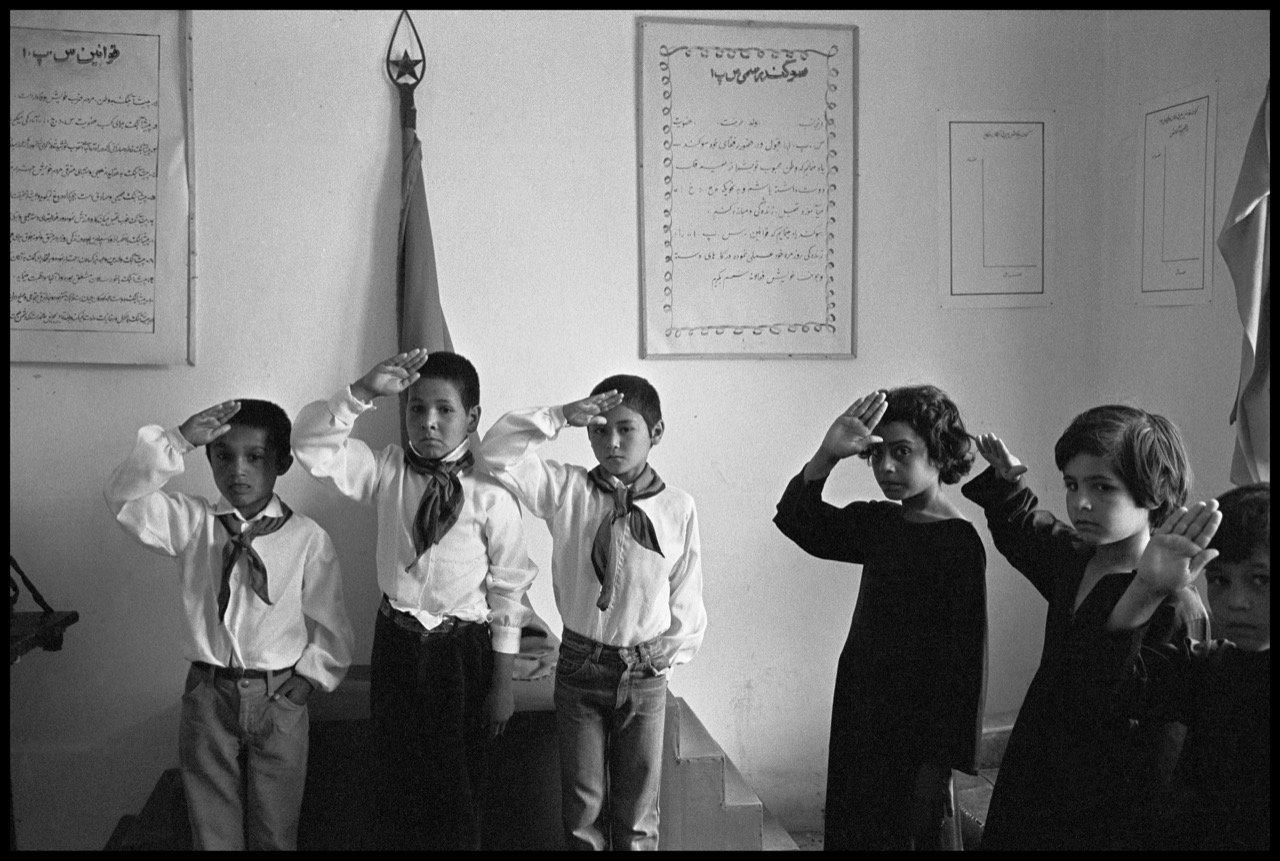

1986, 1992, 2001: Abbas

Abbas traveled to Afghanistan in 1986 to cover the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan through the lens of its Afghan regime allies rather than through the US-supported mujahedeen, with whom they were at war. He returned in 1992 and 2001. Excerpts from his initial impressions:

“I experienced a kind of permanent schizophrenia throughout my six weeks’ stay in Afghanistan. Reality did not always coincide with what the Party wanted me to see.

I was completely free to go wherever the Party wanted me to go, that is to say only in the zones controlled by the regime. It was out of the question to go to Kandahar, Herat, Ghazni or Bamyan, though these are regions that are interesting because the rebels are active there…..A ‘journalist’ accompanied me everywhere and, as I learnt from one of his colleagues, he reported every morning at the offices of the Secret Service. I could photograph whatever I wanted — except for the Afghan army, or the Russians, civil or military.”

“All my visits to institutions were, of course, organized, but my guides never tried to influence what pictures I took or what questions I asked. I speak fluent Farsi (which Abbas said was very close to the official language, Dari) and thus I did not need an interpreter. But the liberalism of their attitude was remarkable for anyone who knows Eastern Bloc countries where one is only allowed to see what is ‘positive.’ My Afghan guides never tried to hide the great poverty of their country.”

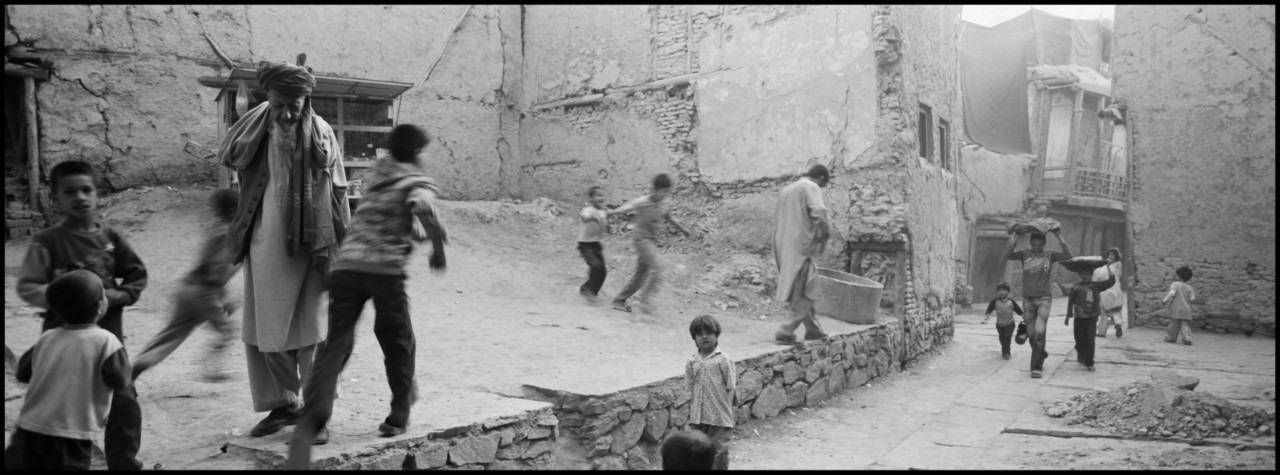

“Has the West ever seen anything in the clarion call of the Afghan resistance movement but a method to contain what it sees as Soviet expansionism? Has it ever troubled itself about the fate of the Afghans themselves?………..This reportage on Afghanistan was also, for me, a step back in time. An Iranian, nostalgic for his own country, I very quickly found my own roots here. A proud and dignified people, welcoming and generous… A turquoise sky and the light of the high Asian plateau…the ochre-coloured dust … the evening chant of the muezzin…the roses, extraordinary roses…”

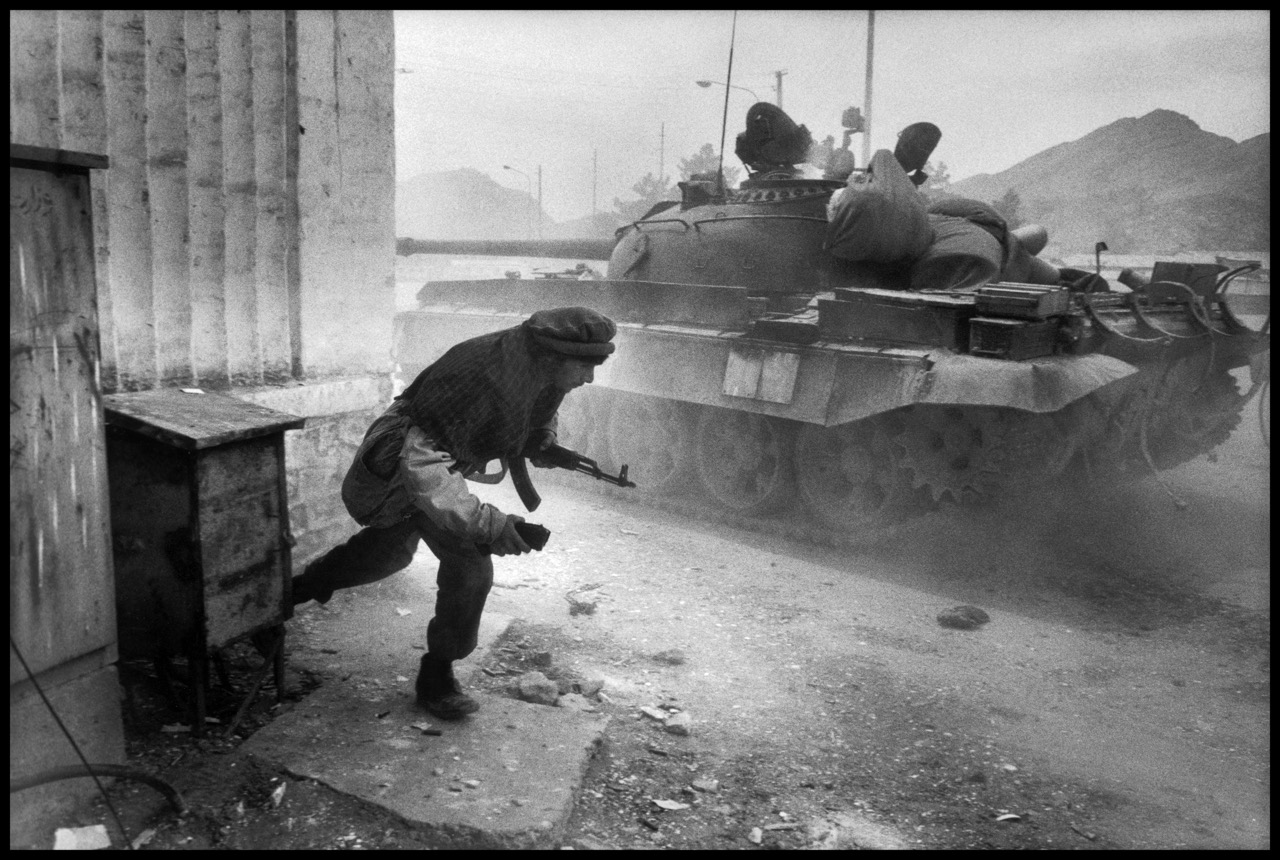

1994–1998: Chris Steele-Perkins

August 2021 has brought daily news alerts on the Taliban’s rapid advance in taking over territory unhindered by Afghan government troops. In mid-August, US officials estimated Kabul could fall in less than a month. In reality, the Taliban was in control in the capital, except for the airport, only five days later.

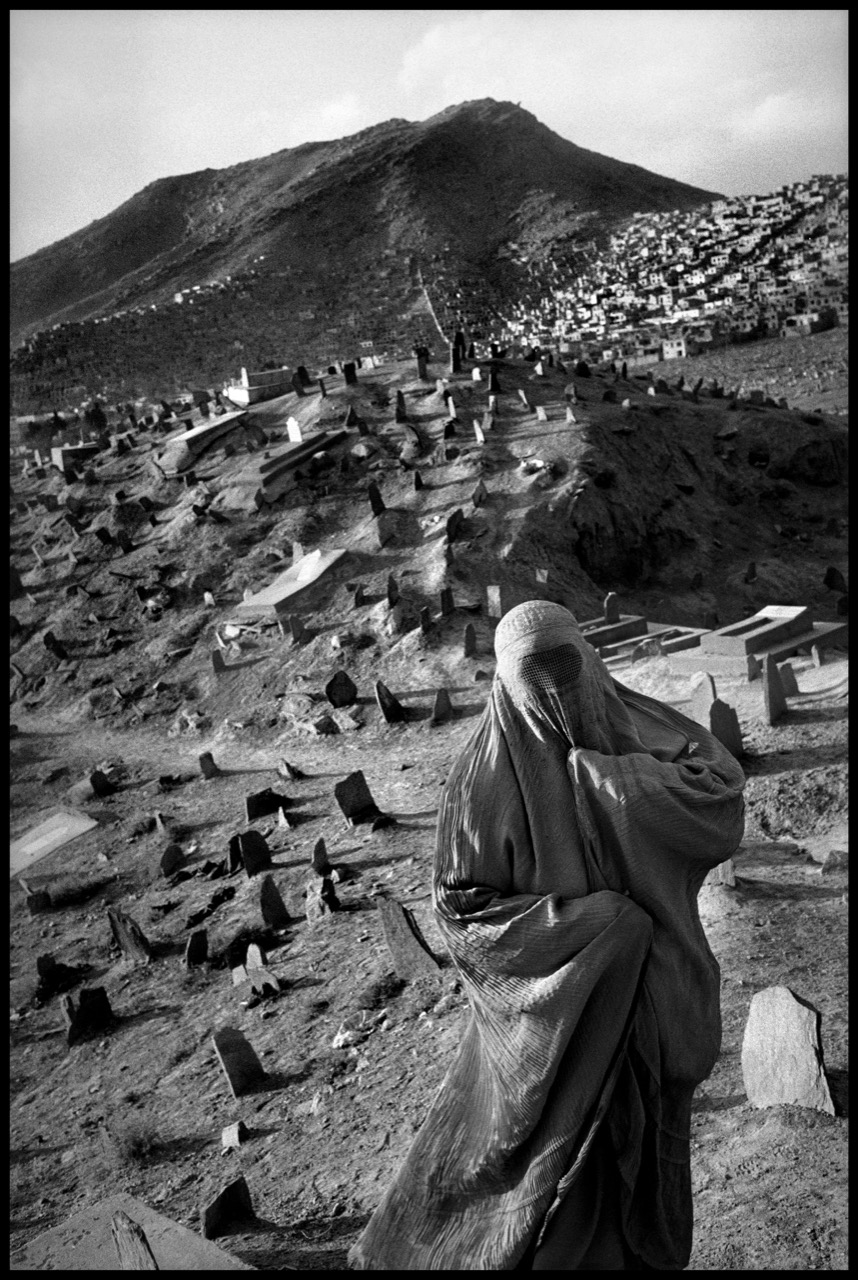

Chris Steele-Perkins provides a blueprint in documentary photography of what’s to come in Afghanistan with his coverage throughout the 1990s. These images taken from 1994 to 1998 document the destruction of Kabul: residents turned to refugees and women receding into the background. Steele-Perkins recalls that, in 1996, it seemed the capital fell overnight to the Taliban. “They just moved in,” he said. “It wasn’t like a huge fight or anything. To wake up in the morning and to be told Kabul had fallen, it was very undramatic.”

Here’s his remembrance of the first days in September 1996:

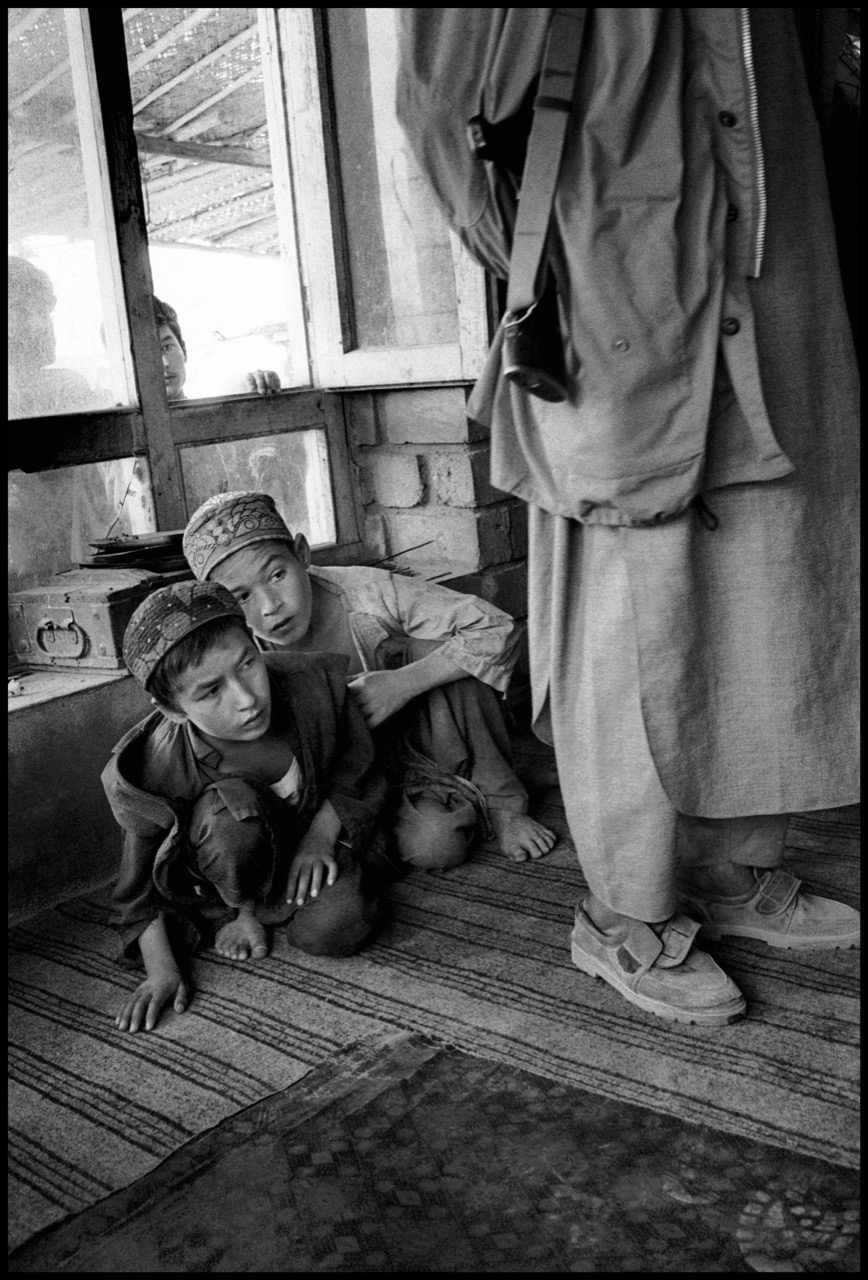

“The Taliban hold the airport. We ask for permission to photograph. A young mullah comes out of a building. He is barely in his twenties — soft over-fed body and chubby, creaseless face. He can know nothing about fighting, yet he is in command. He gives us permission as long as we do not photograph the soldiers, and then disappears inside again, unconcerned over whether we follow his instructions. A battered truckload of young men pulls up and they tumble out covered in dust from their journey. They are new volunteers we are told, straight from the madrassas, the religious Koranic schools. ‘We have come to fight for Allah,’ they all proclaim. A rusty container is opened which contains an armory of automatic weapons, old AK-47s already ruggedly used. They all surge forward as the weapons are distributed. They are unsure, handling them awkwardly, feeling their weight, fumbling to take the clips off. Some stick flowers down the barrel. They laugh nervously and scramble back on the truck, wave their weapons in the air. Now they are men. Fighters for Allah.”

2001: Alex Majoli

After becoming a full member of Magnum Photos in 2001, Alex Majoli covered the fall of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, and two years later the invasion of Iraq. In Majoli’s words:

“‘I come from a country that no longer exists, you see. I come from Afghanistan,’ a man told me in Rome years ago.”

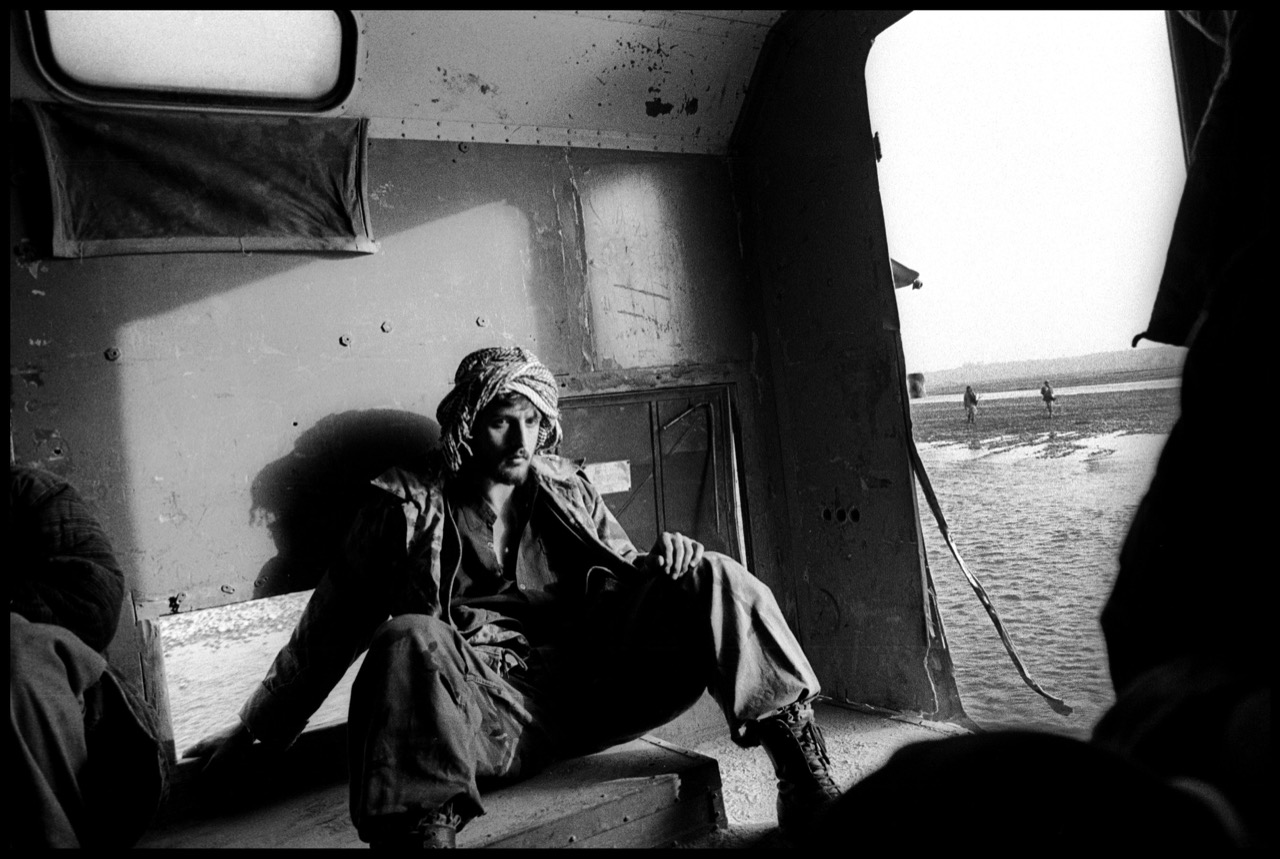

“I went to Afghanistan two weeks after the September 11th terrorist attacks. For my first trip into Afghanistan, I followed the Northern Alliance troops located in the north town of Dasht-e-Qala. I spent almost 20 days waiting between the front lines and the ‘journalist force headquarters’ in Khoje Bahauddin for an offensive that never arrived or at least didn’t arrive on time for my assignment deadline.”

“I was not ready enough for this war. Technical stuff like satellite phones (preferably ISDN), digital cameras, electric generators, long term support from the magazine and, of course, a thorough determination from the photographer was the only way to follow the events in Afghanistan. These words are not an excuse, but a preface for the photos you are going to see. When I came back for the second trip I worked almost all the time in Kabul. Before I left the country I stopped in Tora Bora for 10 days. Tora Bora is just one of the thousands of names given to that range of mountains.”

“I never really understood where I was in this intense barren country.”

2001–2011: Moises Saman

Magnum photographer Moises Saman first traveled to Afghanistan in the weeks following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, while on assignment for Newsday, the New York-based newspaper where he was employed at the time. Over a 10-year period, he made multiple trips. Saman talks about his memories, how Afghanistan shaped his photography and an image that still has an emotional effect on him a decade later.

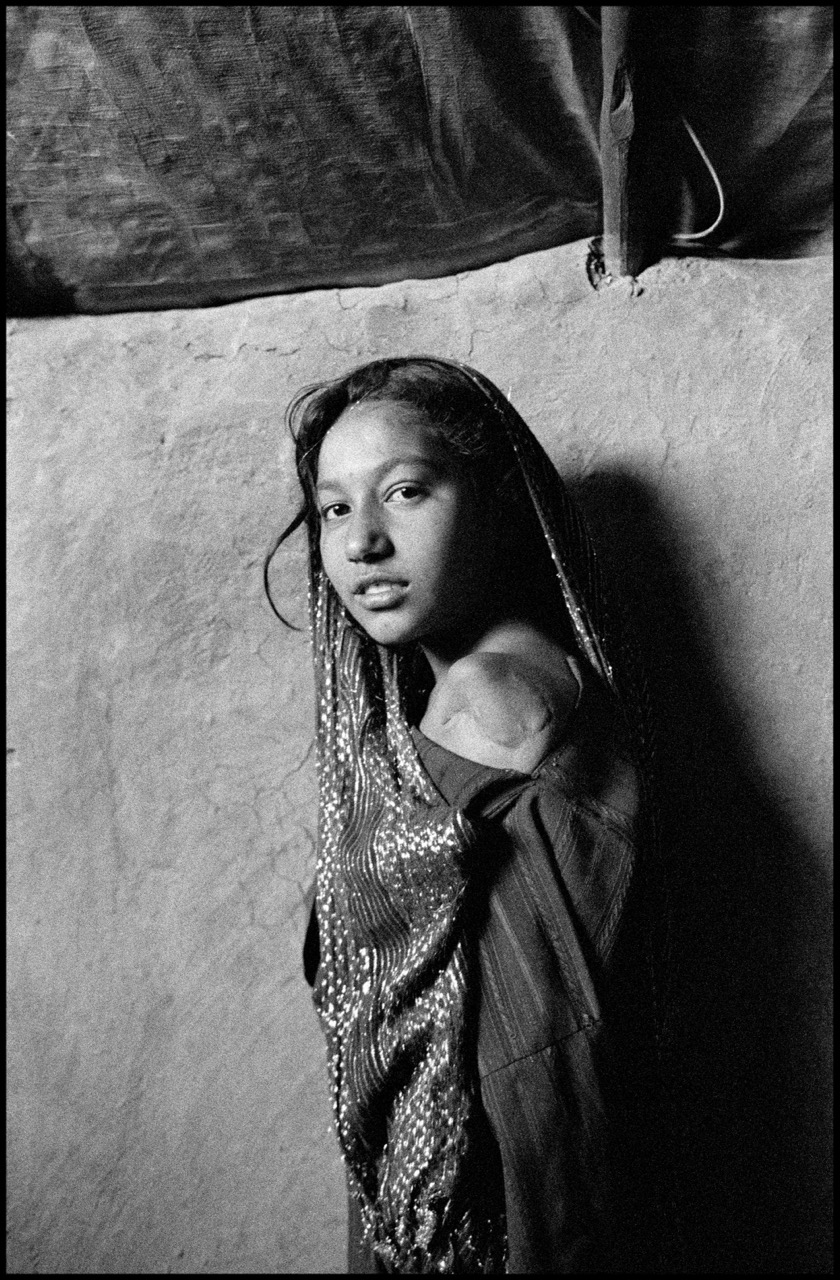

“The beauty of the imposing mountains and rugged terrain, and the scars of decades of war that are visible everywhere,” Saman says, reflecting on his work in the country. “I mostly remember the children, Afghanistan’s youngest generation, and the countless times I was inspired by their toughness, and ability to make the best despite their condition.”

“The opportunity to return over a period of 10 years certainly opened my eyes beyond what was on the surface, and hopefully this gained experience is reflected in my work. I find that during these long relationships there is a moment when you shift from reacting to the “news” to trying to find your own answers, and that is when your visual language also changes to become more personal.”

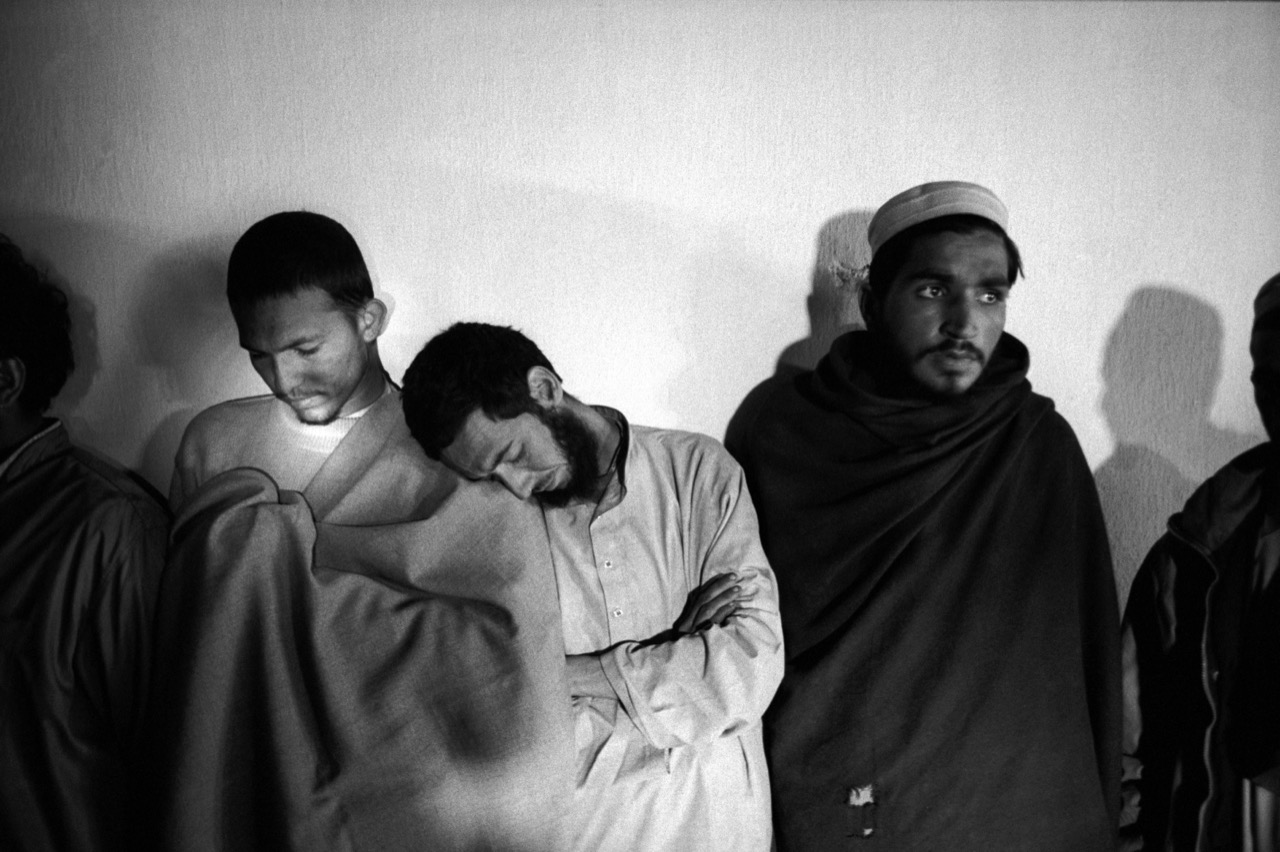

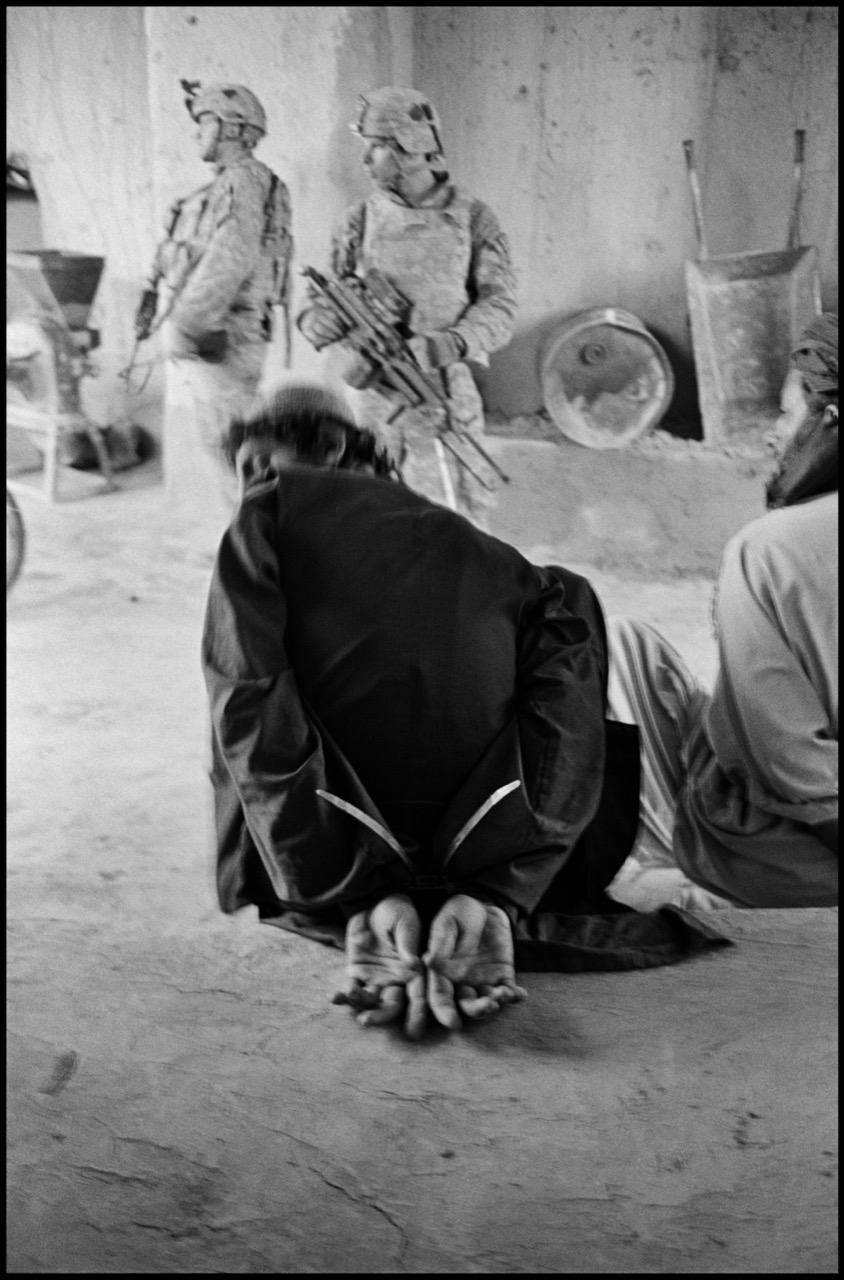

“One of the most emotionally affecting of my images is amongst the last photographs that I made in Afghanistan, in 2010, depicting a meeting of elders in Marjah, Helmand Province, with the newly U.S.-appointed provincial governor. The village had just been taken from the Taliban after heavy fighting, and the U.S. was implementing a strategy known as ‘government-in-a-box’ which immediately failed. I remember feeling the energy in that room, the distrust between the people there and an impending sense of doom about the future.”

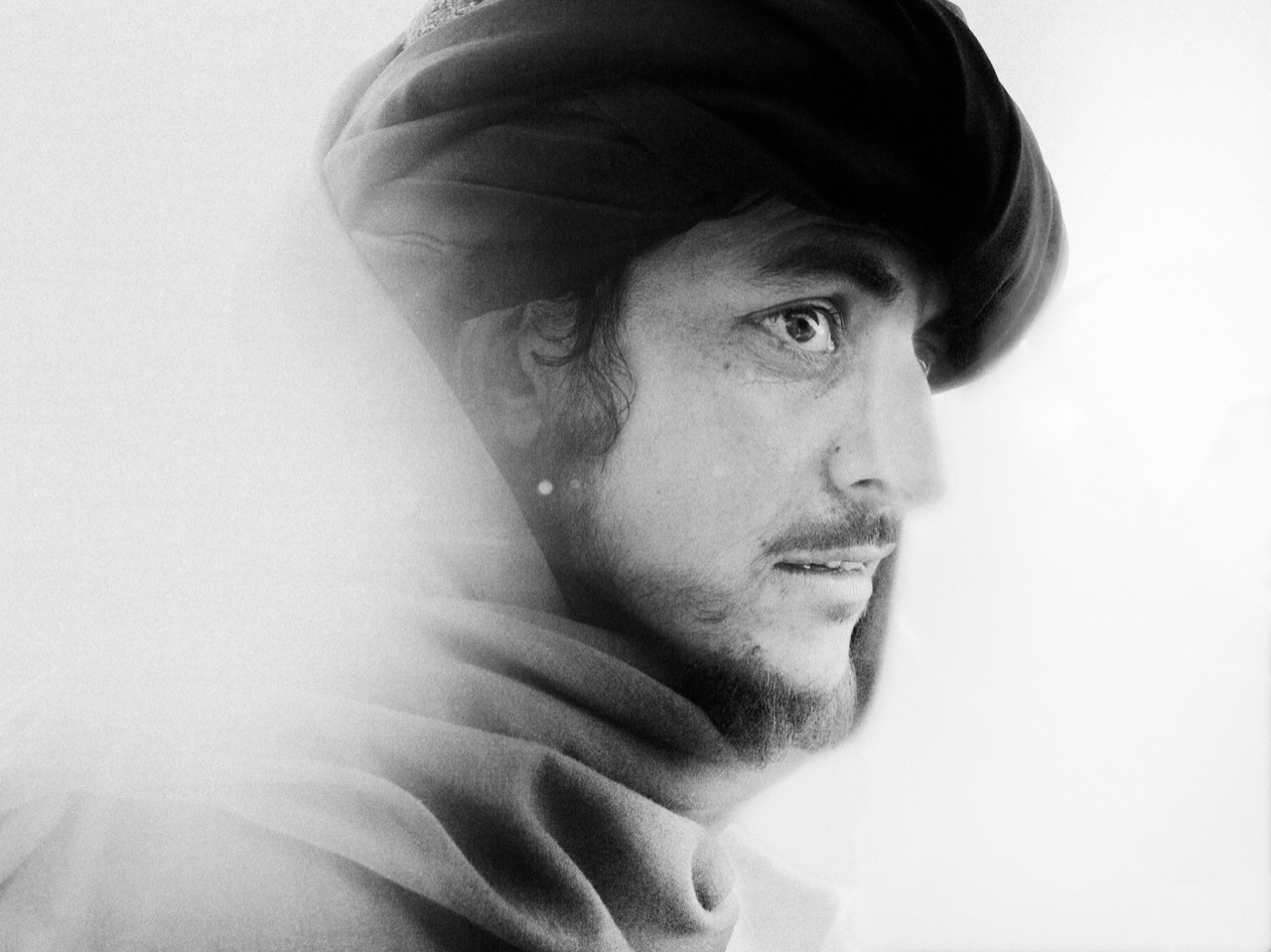

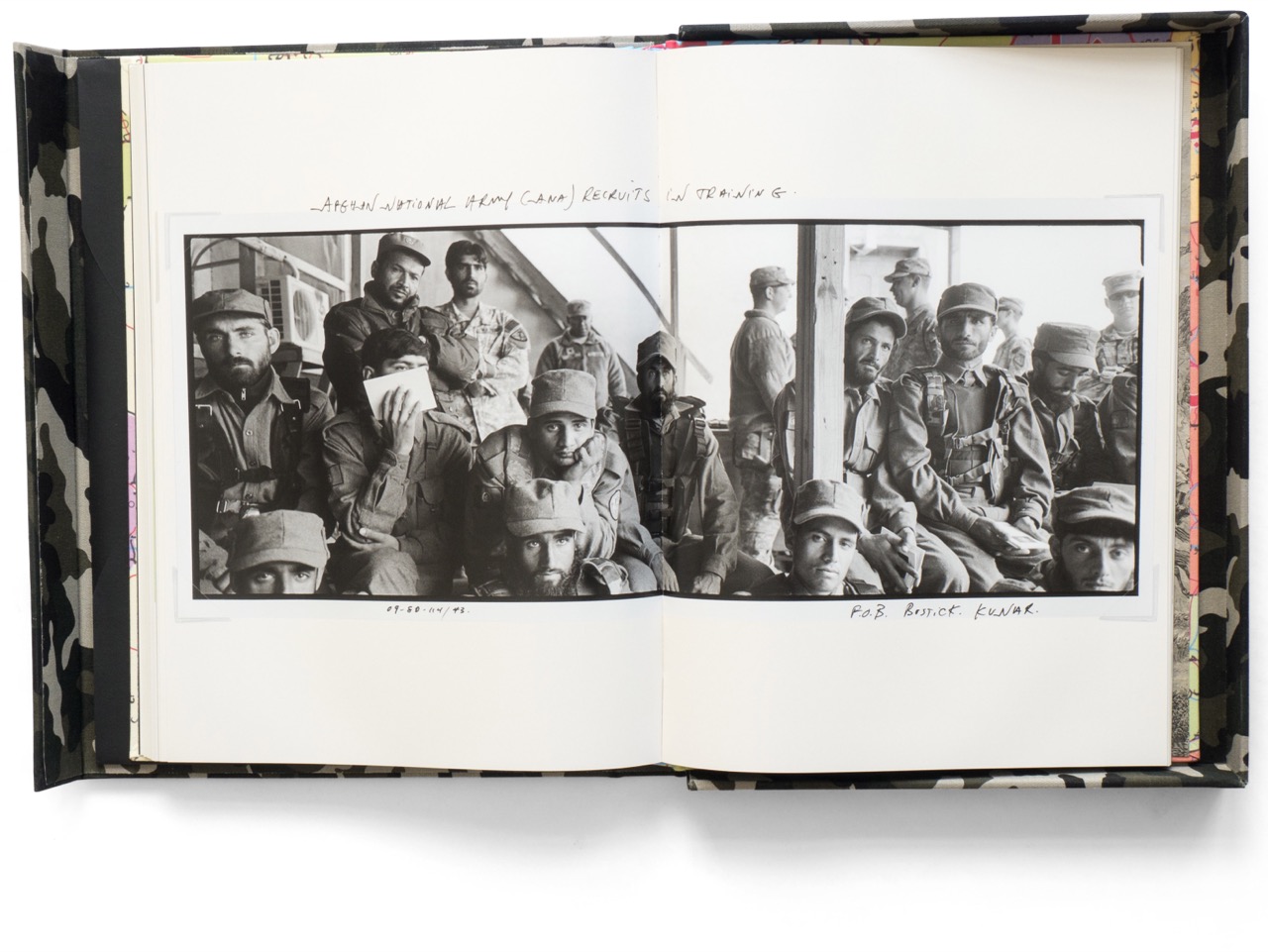

2001– 2013: Thomas Dworzak

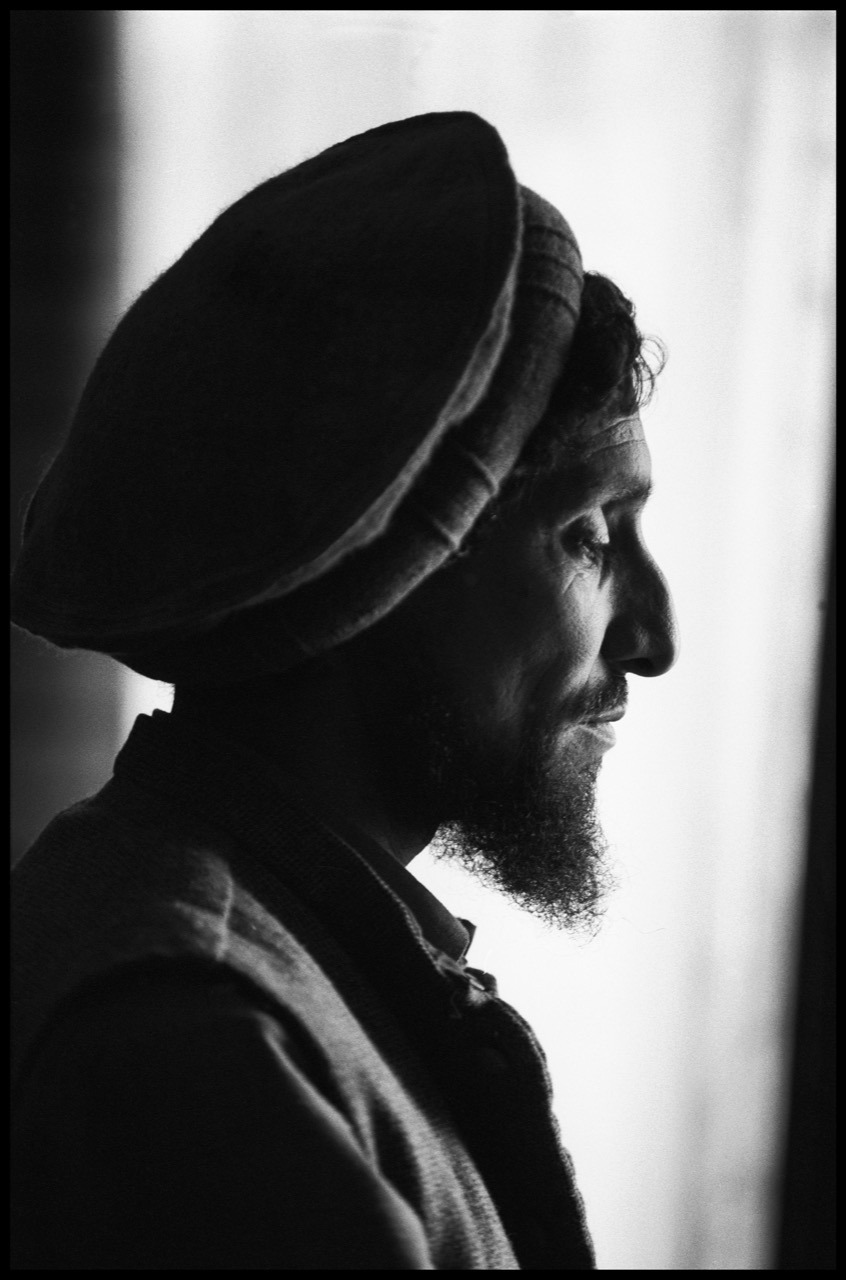

Two weeks after the 9/11 attacks, Magnum photographer Thomas Dworzak was in Afghanistan. He followed the Northern Alliance, which was regrouping after the assassination of its military leader Ahmad Shah Massoud in an al-Qaida and Taliban plot prior to September 11. Dworzak travelled documenting the group —which received U.S. military support— in their fight, all the way to Kabul and then to Kandahar, the Taliban heartland.

Since 2004, he has been documenting the Georgian military, which had joined what former US president George W. Bush called the “coalition of the willing” along with the US and NATO’s war efforts in Iraq and then Afghanistan. In an alignment that had less to do with Afghanistan and more about Georgia’s desire to be protected by the West from Russia, Georgian soldiers trained, fought and died. Dworzak captured intimate moments in Tbilisi, including an elderly mom saying goodbye to her military officer son, soldiers blessed by priests during training in Germany, and the first Georgian soldier who died in action as he was returned to his mountain village to be buried.

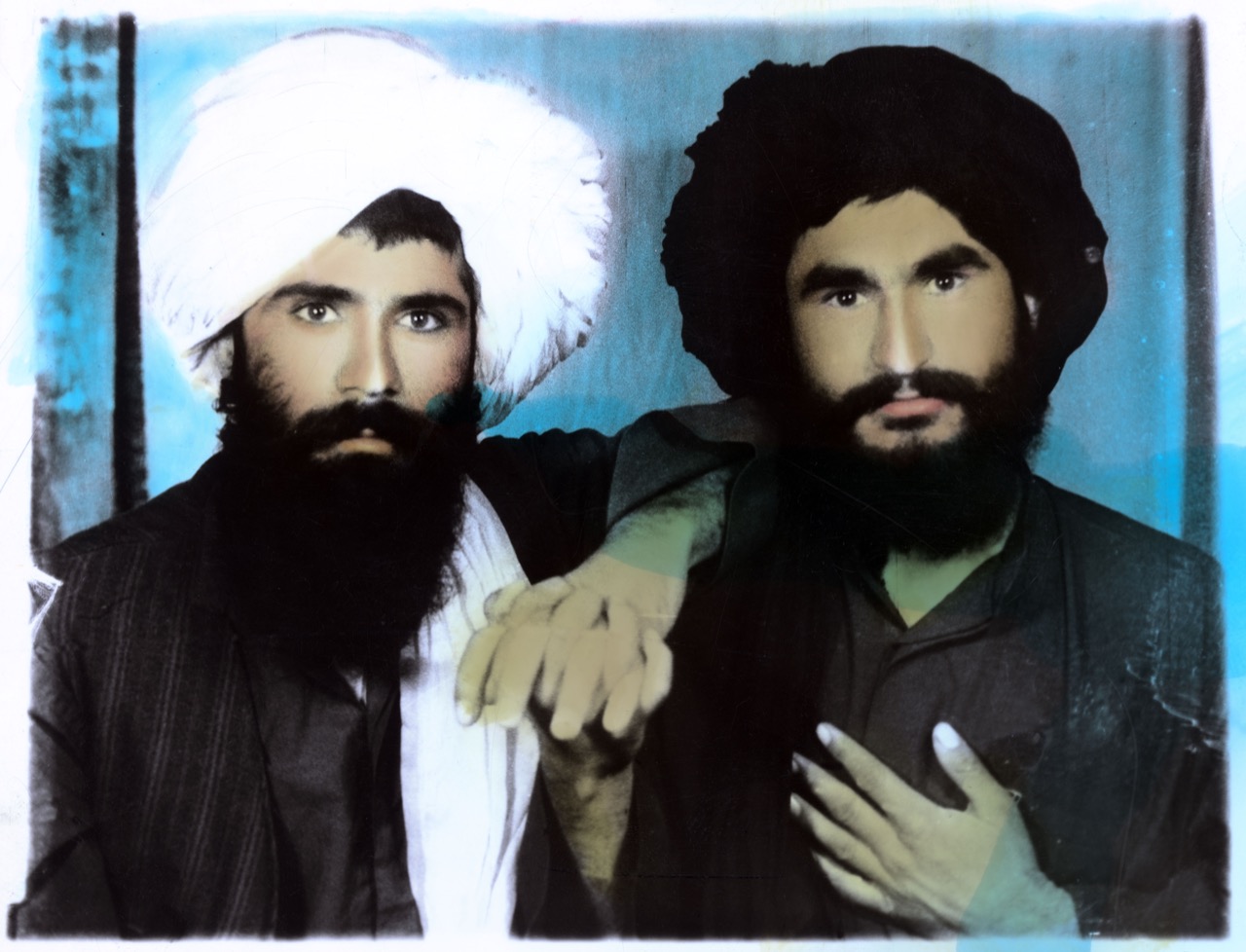

Dworzak collected studio portraits of Taliban soldiers during his coverage of the fall of the Taliban regime in 2002. It is thought that most of these images made by a Kandahar studio photographer are of Taliban soldiers who sat for portraits in early November 2001, but could not pick them up as they had to flee the advancing opposition and U.S. bombing. He was intrigued by the dichotomy of the Taliban as a brutal fighting force and the camp aesthetic of these highly retouched images of soldiers who had asked that flattering portraits be taken in secret in the back room of a photo studio. The Taliban eschewed photography of the living in its interpretation of Islamic rules. Later, that restriction was lifted to allow passport photos.

2004, 2010: Jerome Sessini

Magnum photographer Jerome Sessini was in Pakistan just after 9/11 in 2001. Unable to enter Afghanistan, he stayed in Pakistan to cover the issues of illicit opium cultivation, heroin production and weapons manufacturing. Three years later, he had the opportunity to work in Kabul as he was interested in documenting the impact of drug abuse on the local population.

“Afghanistan is known as the largest heroin producer and trader in the world, but locals are the most severely impacted by heroin and opium use – young, old, women and men. When I traveled there I could see all kinds of people who were for different reasons hooked on heroin.”

On multiple occasions, Sessini was embedded with the French military and the U.S. Marines.

“I was with the Marines for a month in Helmand province in 2010. My partner for patrols was a 20-year-old old Marine, from Trenton, Georgia. The last day he asked me to join a group of 10 for a risky patrol deeper into Taliban territory. I was tired and I preferred to go to Kabul for a break. When I arrived at the military camp in Kabul, I received an email from 1st Lt. Scott Cook, who commanded the squad I was just embedded with. My partner, Lance Cpl. William Richards stepped on an IED and died on the field in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by Taliban, which had prohibited helicopter rescue.”

2008—2011: Larry Towell

“On September 11, 2001, several Magnum photographers and I were in New York City the day the Twin Towers were hit. I had been near the base of the World Trade Center when the second building collapsed, and escaped being buried alive in a tornado of debris by jumping into what I remember as a hotel lobby,” says Larry Towell.

“The day’s events scared me, but not as much as the sight of the most powerful head of state on earth declaring on TV, in the language of the Wild West, an open-ended war with no exit strategy against an enemy that had no state, no borders. In military terms, it was unwinnable. You cannot kill a ghost with a gun, a ghost that thrives in the shadows of failed nation states. It is time to rethink the War on Terror.”

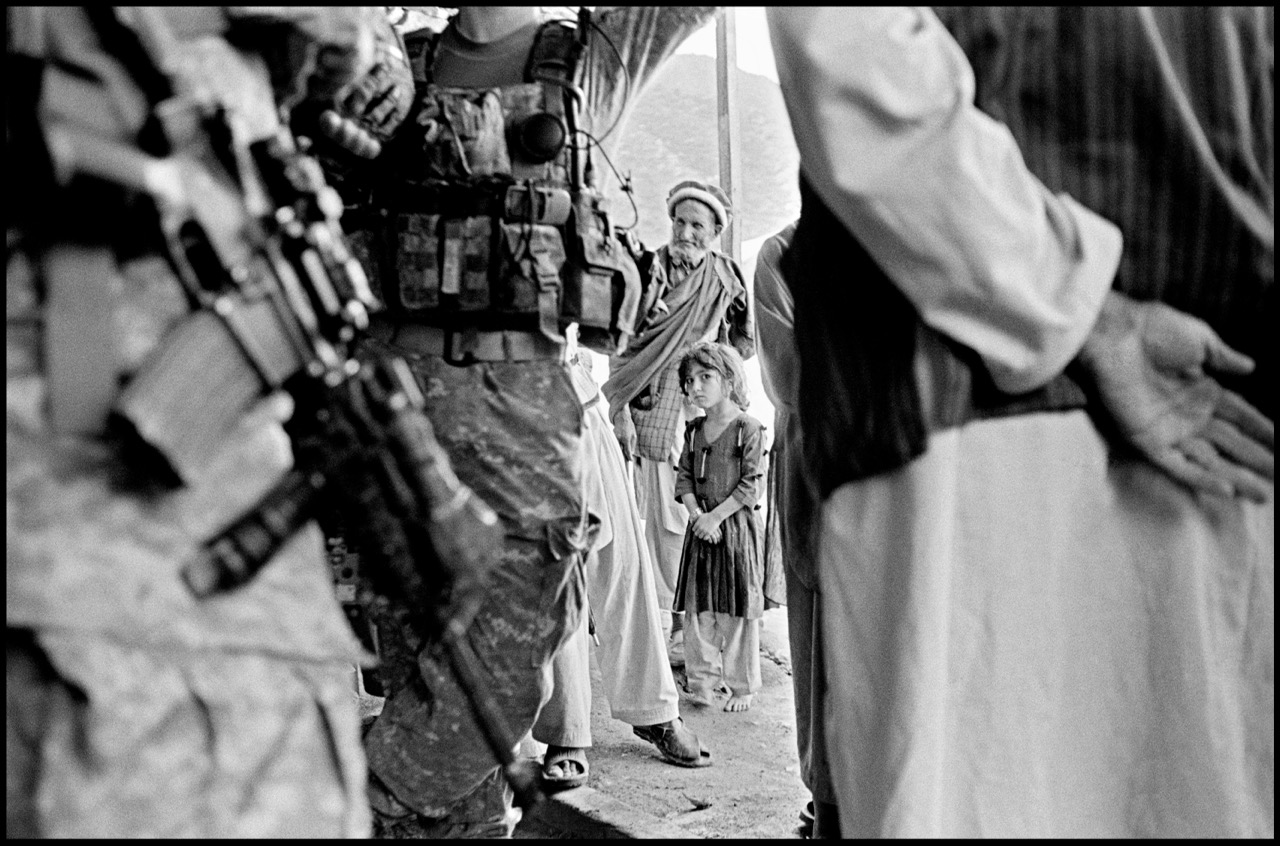

“I photographed the shell-shocked people of this disfigured land between 2008 and 2011. By the end, it got under my skin and into my soul; it frayed me at the edges because I made friends there that I cared about. Three of the five Afghan colleagues I worked with had to flee the country due to death threats for working with foreigners, which is common in conflicts where the lines become blurred between occupation and military campaigns parading as foreign aid, and between journalism and propaganda created by embedding with troops.”

“As one trip followed the next, it became increasingly dangerous to step outside my hotel room, even in Kabul, let alone drive into villages, except in a military vehicle—preferably one hovering in the air. The insurrection was growing stronger, meaning the insurgents were winning at a grassroots level in areas where people had suffered most from conflict, neglect, and corruption. At the onset of the war, the official narrative was that it was winnable, that the Americans would soon beat the bad guys, that the Afghan National Army (ANA) would maintain the status quo after being professionalized by their trainers, and that, while the U.S. was still expanding infrastructure, they were also withdrawing. That narrative has fallen apart.”

2007–2009 and ongoing: Peter van Agtmael

In 2007 and 2008, Magnum photographer Peter van Agtmael spent several months embedded in the remote American outposts of eastern Afghanistan. Following this, he worked without an embed in Kabul and in the northern part of the country. When not in Iraq and Afghanistan, van Agtmael photographed the war at home, following the recovery of wounded soldiers and the families of the fallen. Van Agtmael describes his experience:

“I first went to Afghanistan in 2007. I’d been covering the war in Iraq, which largely dominated the news coverage at the time. I began to wonder what was happening with the American presence in Afghanistan and arranged for an embed. It was a completely different war. I went to the east, where fighting was beginning to escalate in the mountains. I was shocked by the tiny American presence tasked with the vague mission of interdicting insurgents coming in from Pakistan. The mountainous landscape was utterly vast, whole valleys patrolled by a few dozen Americans, and even fewer Afghan allies. I remember asking a young commander what would happen if they were able to control the valley. He looked at me like I was insane and said, ‘They’ll just go to the next one where we don’t have a presence.’”

“It’s hard to pick my strongest memories, but I suppose they are from the first small patrol base in the Pech Valley I embedded in, nicknamed “California.” The unit was in the last weeks of a 15-month tour. They were covered in dirt and filth, and lived in bunkers that looked like World War I. Quite a few soldiers were regularly smoking hash with the small Afghan unit stationed there. The leadership barely ran patrols. Stray dogs wandered around, and periodically children from the neighboring village would come to sell food to the soldiers sick of MREs. I ate some, got terrible food poisoning, and remember sweating through a mortar barrage hoping I wouldn’t lose my lunch all over the cramped bunker. The Marine adviser I was with couldn’t stop giggling at my predicament. He was killed not long after.”

“From the beginning, it was hard to imagine Afghanistan as a winnable war. The geography was vast, the rural population was generally incredibly hostile to the Americans and their Afghan proxies, and the grand strategy seemed muddled at best. This dissonance between the vast war machine lurching forward and the unsustainable conditions on the ground shaped the way I worked.”