Desert Journey

The personal diaries of Magnum co-founder George Rodger reveal the reality of a World War II African assignment

The early days of of photographer and Magnum co-founder George Rodger’s career were dominated by his documentation of war. His photographs of the Blitz in London caught the attention of Life Magazine, which quickly went on to hire him as a correspondent. Over the next seven years Rodger would proceed to travel across sixty-one countries and cover over eighteen military campaigns for the publication. The first of his foreign assignments took him to the African front during World War II to document the North African War between 1940 and 41. Rodger went on to publish the resulting photo-essay, along with his extensive diary entries from the period, as a book titled Desert Journey.

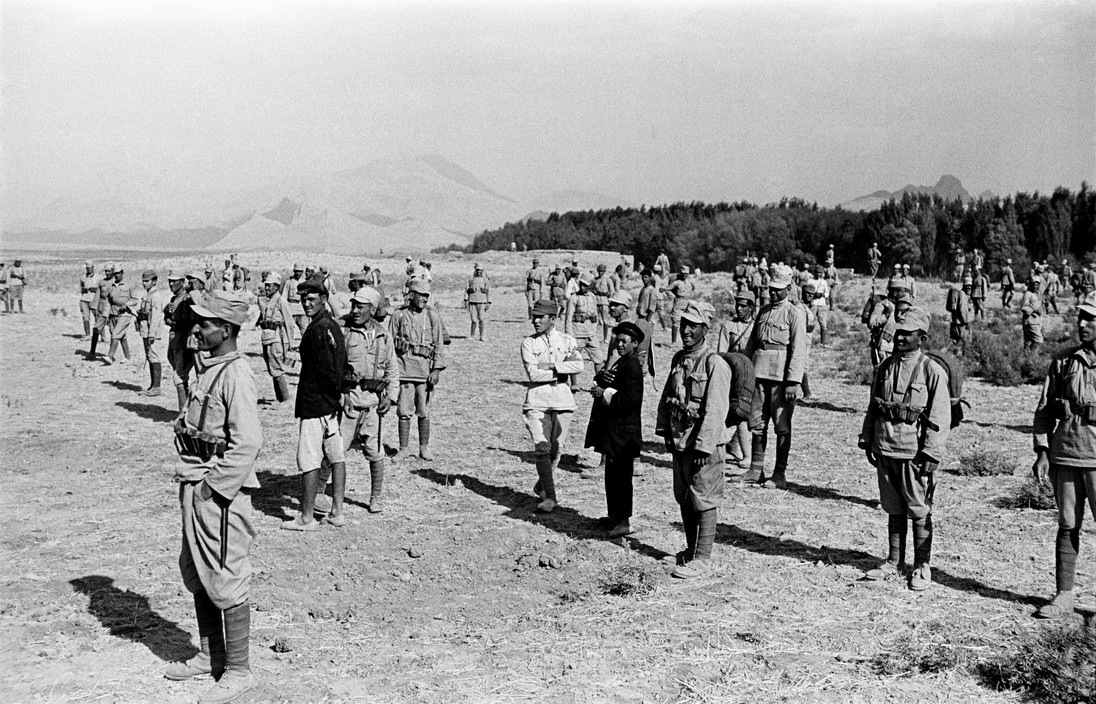

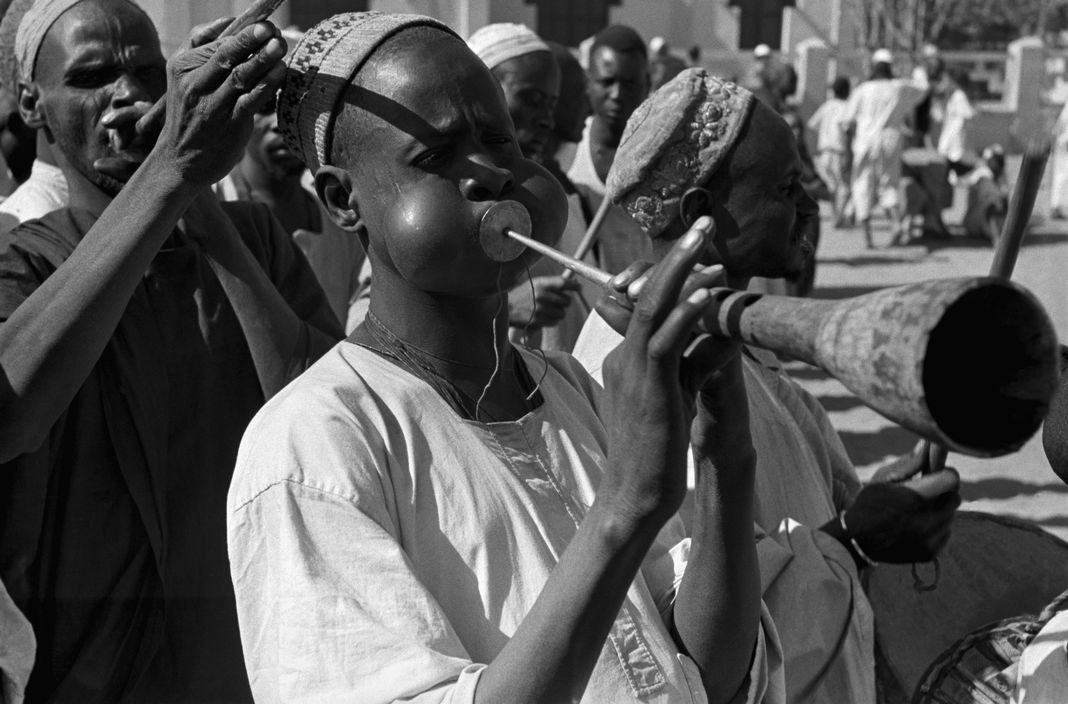

Initially sent on a month-long commission by Life to document the activities of the Free French Army at their headquarters in Douala, in the French Camerouns, George Rodger took that long to reach his destination by boat. Instead of returning to England he remained in the country and spent much of the next two years traveling alone throughout the region. Never having worked abroad before, Rodger operated in conditions that were unprecedented for even the most seasoned of war correspondents. With limited contact with his editorial board in London and no clear route to follow, Rodger navigated the situation to the best of his ability, on his own.

Pursuing the Free French Army, which was fighting to resist attempts by the Axis powers to capture parts of the region, Rodger journeyed from Douala across vast expanses of the Saharan desert into Eritrea, and then zigzagged between Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Syria and Libya. Capturing in detail the conflicts he encountered and his experience of that first assignment abroad, Desert Journey offers an insight into his early days as a photojournalist and is a testament to the spirit of adventure that became a definitive quality of Rodger’s practice. Indeed, he would go on to spend the rest of the war photographing the liberation of France, Belgium, and Holland by the Allies, before giving up war reportage completely after the traumatic experience of photographing the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

"The book is more a saga of travel than a chronicle of war … I write only of what I saw"

- George Rodger

Driven by a restlessness and desire to adventure, Rodger initially had aspirations to become a writer, so text dominates his early documentation of these travels. It was only much later in his career that his photographs began to take center stage. Writing in the foreword to Desert Journey, he describes his meticulous note-taking as a means to record his experiences for himself and his friends, as opposed to offering any analysis of the political and humanitarian upheavals he was witnessing: “the book is more a saga of travel than a chronicle of war … I write only of what I saw,” he wrote. Nonetheless, through text and image Desert Journey provides an invaluable insight into a significant historical event and lesser-documented part of World War II. Excerpts from his diary, giving insight into moments of his extensive travels, are presented here, alongside photographs from the book shot over the two years he spent in this region.

Arriving in Africa

“Once on the hot and humid soil of Africa with the bast expanse of the unknown continent before me, I soon learned the difference between pampered photojournalist in London and solitary photojournalist in unknown Africa. The disadvantages were legion, daunting. Although the continent of Africa was four thousand miles from west to east, there were no planes, no public transport of any kind – only camels north of the Camerouns. There was no possibility of processing film, no way to ship it back to London, and the excessive heat didn’t do it much good.”

“I developed the “package job” system – exposed film sight unseen, captions linked in meticulous numbering of each frame plus a lead-in text, and the whole thing then depended upon the grace of God and the benevolence of the military high command to get it back to London.”

Journeying through the Desert

“I had already learned the necessity for patience and I now added tolerance, because the Free French high command in Douala refused to accept my military accreditation and said I could only work on the culture and economy of the country. The only man who could sort it out was General de Larminat, who was in Brazzaville … He gave me two Chevrolet pickups and a rather dubious baron from Compiegne in France as a liaison officer … All this seemed a bit too much for my first foreign assignment that was already a month past its assignment.”

From Douala to Eritrea

“The date was April 3, 1941, seventy-five days and three thousand miles over-land since I landed in Douala for my four-week assignment. But Cheren had fallen. The gorge leading up to the town was littered with the debris of battle, and there was the awful stench of unburied dead – that sickly-sweet smell one can never forget. I reached the town as the sun was setting, painting in red and gold what remained of the white-washed houses and hiding in weird and savage beauty the ugly wounds of war.”

"I reached the town as the sun was setting, painting in red and gold what remained of the white-washed houses and hiding in weird and savage beauty the ugly wounds of war"

- George Rodger

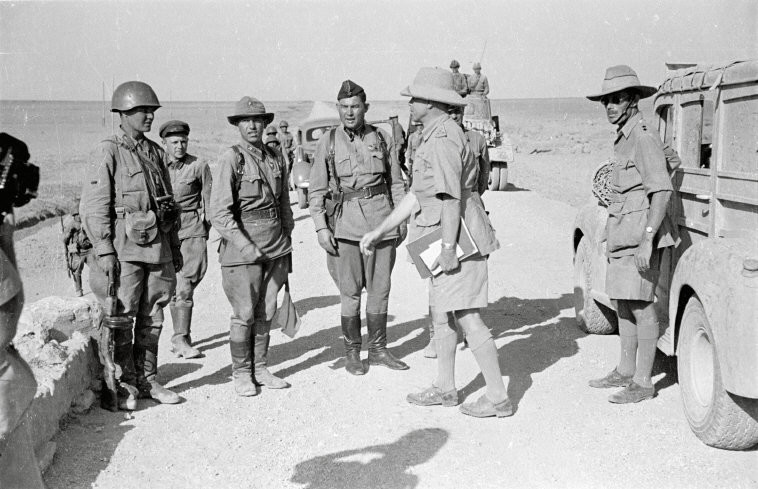

From Cairo to Syria

“On the way to Kuneitra, two Vichy planes noticed my lone truck on the deserted road and decided to dive-bomb it. Their aim was abysmal, and I photographed their bombs falling wide of the target. My truck remained undamaged. I ran from it into the desert – an unwise move. The planes banked, turned, and came back low with machine guns blazing. There was no cover in the barren sand.”

"The planes banked, turned, and came back low with machine guns blazing. There was no cover in the barren sand"

- George Rodger

From Iran to Libya and back to Egypt

“We had just missed the British Airways flying boat to Cairo and there was no other public transport. So we hired a bus. With two drivers. And we drove non-stop through the night, picking up stray pedestrians along the way to add a little weight and hold down the springs.”

“It was a gentleman’s war in the western desert. But non-photogenic Tanks attacked tanks at long range. I spent a lonely Christmas in Benghazi before retreating the whole way back to the Egyptian Frontier.”