W. Eugene Smith’s Warning to the World

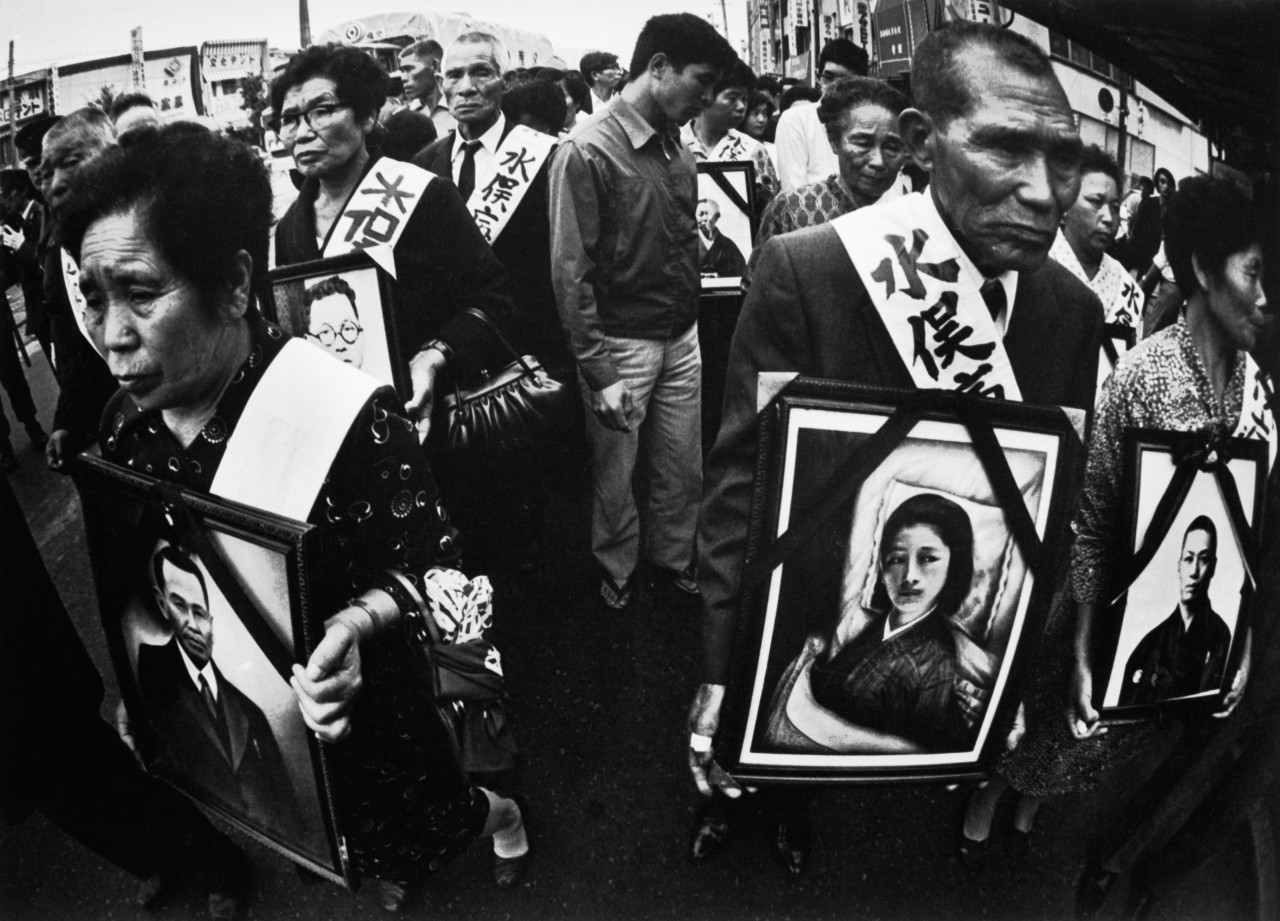

The Magnum photographer made his last photo essay about industrial mercury poisoning in the Japanese city of Minamata, helping to bring justice and visibility to the victims

The photo-essay and subsequent book, Minamata: A Warning to the World, was a collaboration between Smith and his then wife Aileen M. Smith, whose photographs are also featured below.

“Photography is a small voice, at best, but sometimes – just sometimes – one photograph or a group of them can lure our senses into awareness. Much depends upon the viewer; in some, photographs can summon enough emotion to be a catalyst to thought.” So wrote W. Eugene Smith in 1974. A master of twentieth-century photojournalism, Smith was obsessive in the pursuit of his vision. This obsession is perhaps most evident in his long term project documenting the deadly effects of industrial mercury pollution in Minamata. Smith saw the work as a “warning to the world” and ultimately put his life on the line to give a voice to the victims.

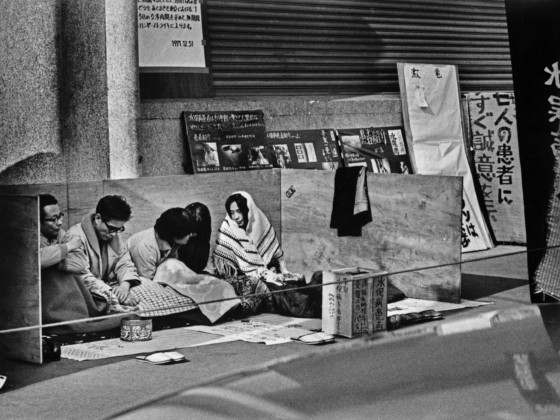

For years, Chisso Corporation’s chemical factory in the Japanese city of Minamata had released methylmercury through its industrial wastewater into Minamata Bay and the Shiranui Sea. This bio-accumulated in the local marine life, leading to thousands of cases of mercury poisoning in the local populace, who ingested the toxic food caught in their fishing nets. For more than three decades, the government and Chisso Corporation did little to prevent the pollution. The company even covered up research that “pointed to [its] recklessness”, as was subsequently reported by The New York Times among others. It wasn’t until 1968 that the government finally issued a statement officially recognising Minamata disease as an illness caused by industrial pollution, and from that point the victims’ struggle for compensation began in earnest.

When Smith arrived in Minamata in 1971 he had already covered the bloody invasions of Tara-wa, Guam and Iwo Jima as LIFE’s WWII correspondent and had produced genre-defining photo essays. But the story made in Minamata would be his last, and arguably most influential, work. Smith became interested in traveling to the city after he was contacted by a member of the Minamata movement. He and his partner Aileen Mioko Smith packed up Smith’s loft in New York, travelled to Tokyo and, now married, relocated to Minamata along with their recently recruited assistant, Takeshi Ishikawa.

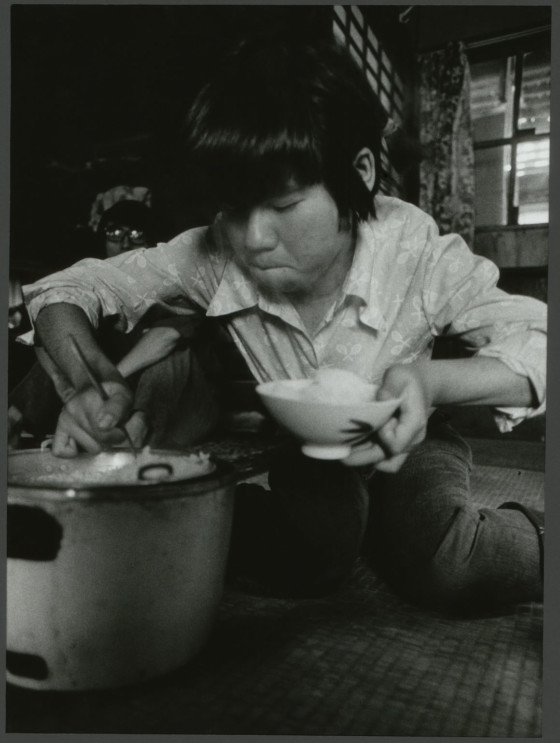

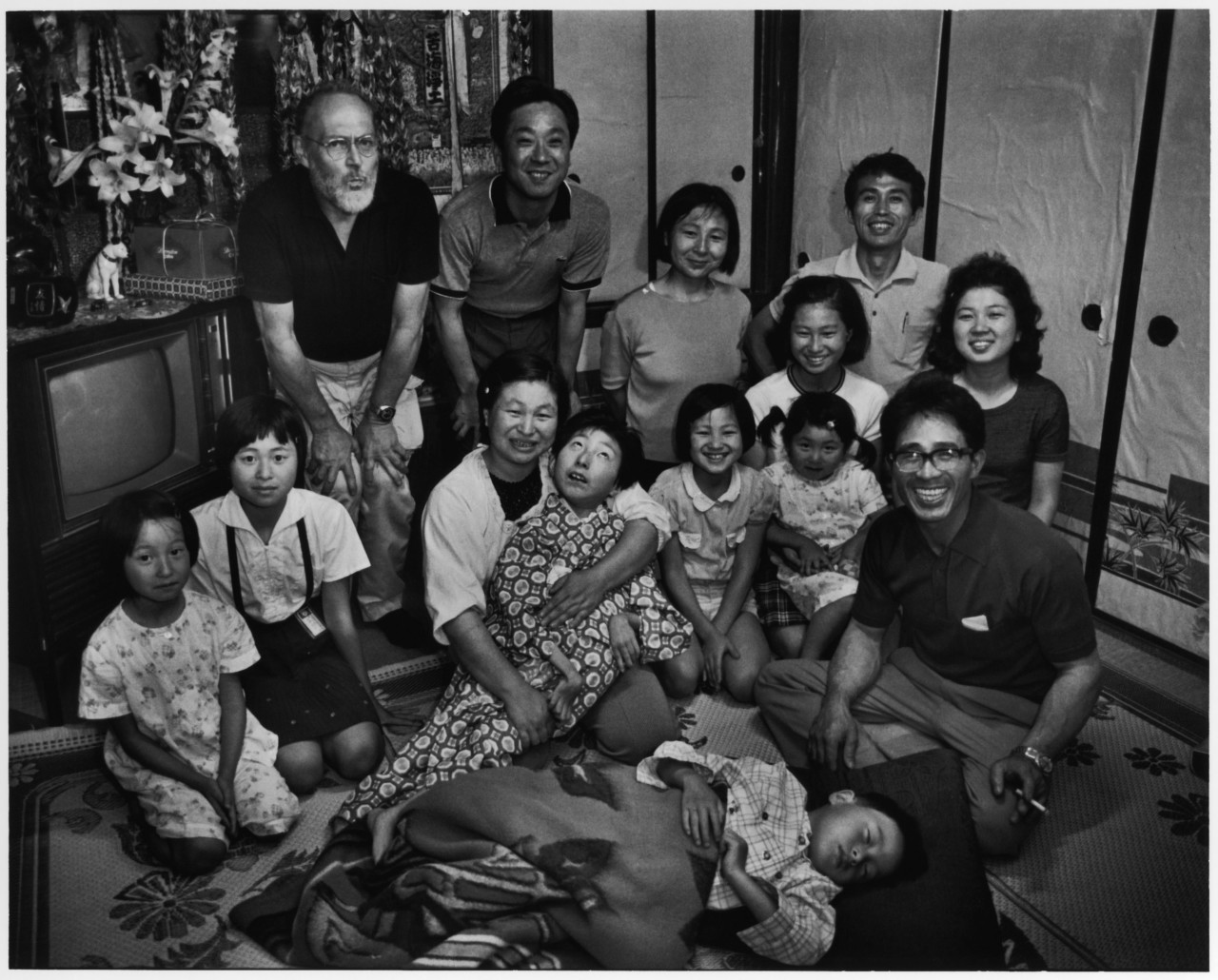

The couple planned to stay for three months but ended up staying three years. “Of course it was very sensitive, we didn’t go barging in,” says Aileen, who photographed alongside Smith on the project and co-authored the resulting book. “We lived there, got to know the people, and photographed. The victims were receptive; the feeling was: ‘We want the world to know’.”

"The first word I would strike from the annals of journalism is the word objective"

- W. Eugene Smith

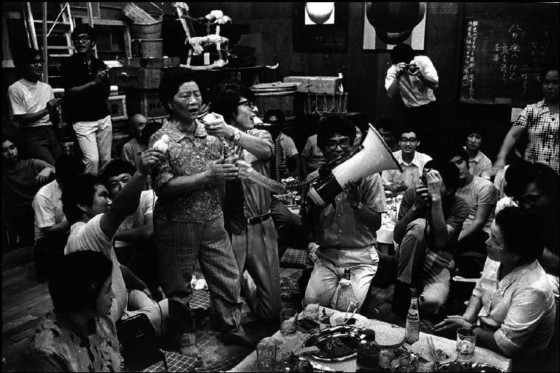

They rented a small house from the family of one of the victims, Toyoko Mizoguchi; the room the Smiths slept in was their altar to her. “I lived with her photograph for three years above my bed. We never met her but she is very deep in my heart,” says Aileen. “Everyone lived really close and during the lawsuit everyone got on the bus and went to the trial; we’d all go together and sleep together in one huge room, all the futons lined up. When you’re like that together you get close!”

Smith’s closeness to the families is a powerful element of the photography. One image—which Aileen has subsequently decided to withhold from circulation out of respect for the family—is called Tomoko and Mother in the Bath. The picture shows a loving mother caring for her daughter, who is contorted by her illness; seemingly unaware of her surroundings. It was taken on a chilly December afternoon in 1971 and would “never have happened if the will of the photographer had merely been asserted upon his subjects,” says Aileen. “He used to say he was like a mouse when he photographed.”

Smith was first and foremost a journalist and he made no secret of his determinedly subjective approach. He put himself—and therefore the viewer—at the emotional center of what he was seeing.

“He would always say: ‘The first word I would strike from the annals of journalism is the word objective’,” says Aileen. “I think you really need to understand the subjects; not worry that if you get close you lose your objectivity and side with them. It was about understanding their reality and what they were really like. We went to Chisso and interviewed them and we wanted to know what Chisso was really like too…they didn’t let us in as much of course.”

Smith is often described as having a thorny character but little is written about his sense of humour. “At Gene’s core was integrity and humour,” says Aileen, who was 31 years his junior. “He was corny all the time. His puns didn’t translate into Japanese but everybody loved him anyway. In the evening our landlord might come over to our house from next door and the two tipsy men would start line dancing arm-in-arm, our landlord singing an old military war song. People asked about the age gap and I would say: ‘Yes, he was so young and I was so old’.”

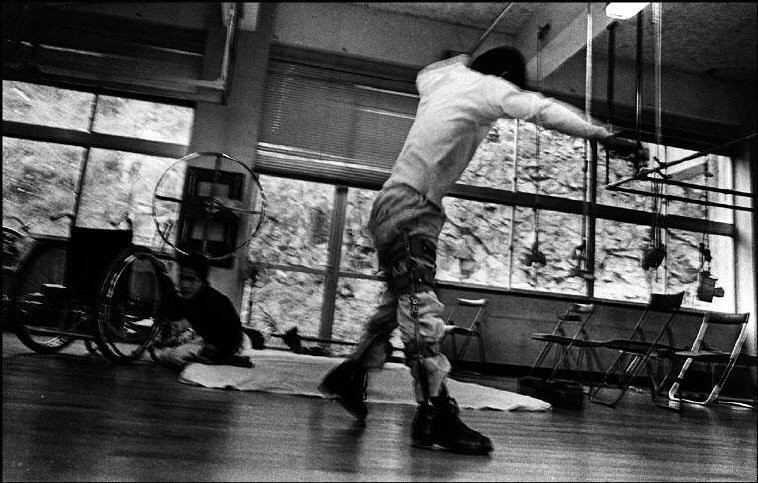

This playful personality translated into his work. His photographs not only showed the victims’ physical and mental pain but also their determination, humanity and moments of joy. In the book Minamata, Smith writes of one patient—the “irrepressible” Isamu Nagai—who “crawls and grabs and has acquired a movie camera and is determined to ‘blast Chisso out of this world’!” Smith was drawn to the strength of the victims, as much he felt bound to bare witness to their afflictions.

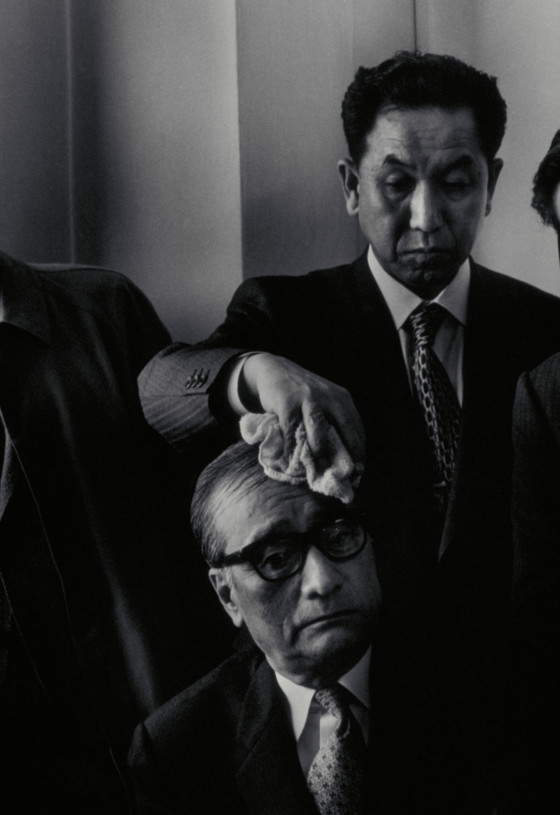

By the time he was working on Minamata, Smith was suffering from his own set of ailments, sustained while photographing in WWII (in the Battle of Okinawa he was seriously injured by mortar fire) as well as injuries from two plane crashes. “He was a body full of pain,” says Aileen. This was to be further compounded after he suffered serious injuries during a confrontation with Chisso employees at a factory in Goi (situated two hours away from Chisso HQ in Tokyo) in 1972. The Smiths had been covering a meeting at the factory when a “goon squad” arrived and told them to “get out or else”—and violence ensued. “They pulled my hair and other reporters got knocked around, but they were heading for Gene,” remembers Aileen.

Smith’s beating was so severe that “the nerve from his finger to his neck was crushed” causing temporary blindness in one eye as well as blackouts when he raised his arm. “It affected him immensely,” says Mioko Smith. “One time he asked me to grab the axe that was used to split firewood and split his head open because he was in so much pain.” And yet he continued to photograph. “For a while when he couldn’t lift his arm up to photograph he used a cable release in his mouth. He already had so many injuries, but it was one more that was really heavy upon us. ”

This was to be Smith’s final photo essay, but the images have taken on a life of their own. Though the impact is impossible to quantify, Aileen says that the images they made are part of the “total effect” which includes the victims’ efforts in winning the lawsuit and the subsequent global media coverage that followed. The photographs were published in LIFE in 1972, toured in global exhibitions and came together in the publication of the co-authored book, Minamata, in 1975.

The photographs are an historical record of the dreadful consequences of industrial water pollution, but has the world learnt from this tragedy? “I’ve had people saying: ‘I read this book at 13 and it changed my life and the work I do now is because of this book,’” says Aileen. Meanwhile, in Barack Obama’s autobiography, when recollecting his childhood, he mentions being moved by seeing a photo in LIFE of a woman holding a crippled child in the bath. When Obama became president of the United States, he was instrumental in moving the country forward in the effort to reach an international agreement to curb the use of mercury. Aileen believes the photo must have been Smith’s photo of Tomoko.

"At Gene’s core was integrity and humour"

- Aileen M. Smith

Still, industrial pollution remains a global catastrophe and the work feels as urgent today as it did nearly 50 years ago. “All these stories of people fighting give courage. Even if it’s not the same issue or continent,” says Aileen, who, as executive director of the environmental group Green Action (Japan), works as an activist against nuclear power. “This kind of communication is really important; rather than just hammering facts, you get to know people, your heart is moved—and that’s what really creates core change.”