Conflicts and Consequences

Paolo Pellegrin on his years of extensive work charting the complexities of the Middle East

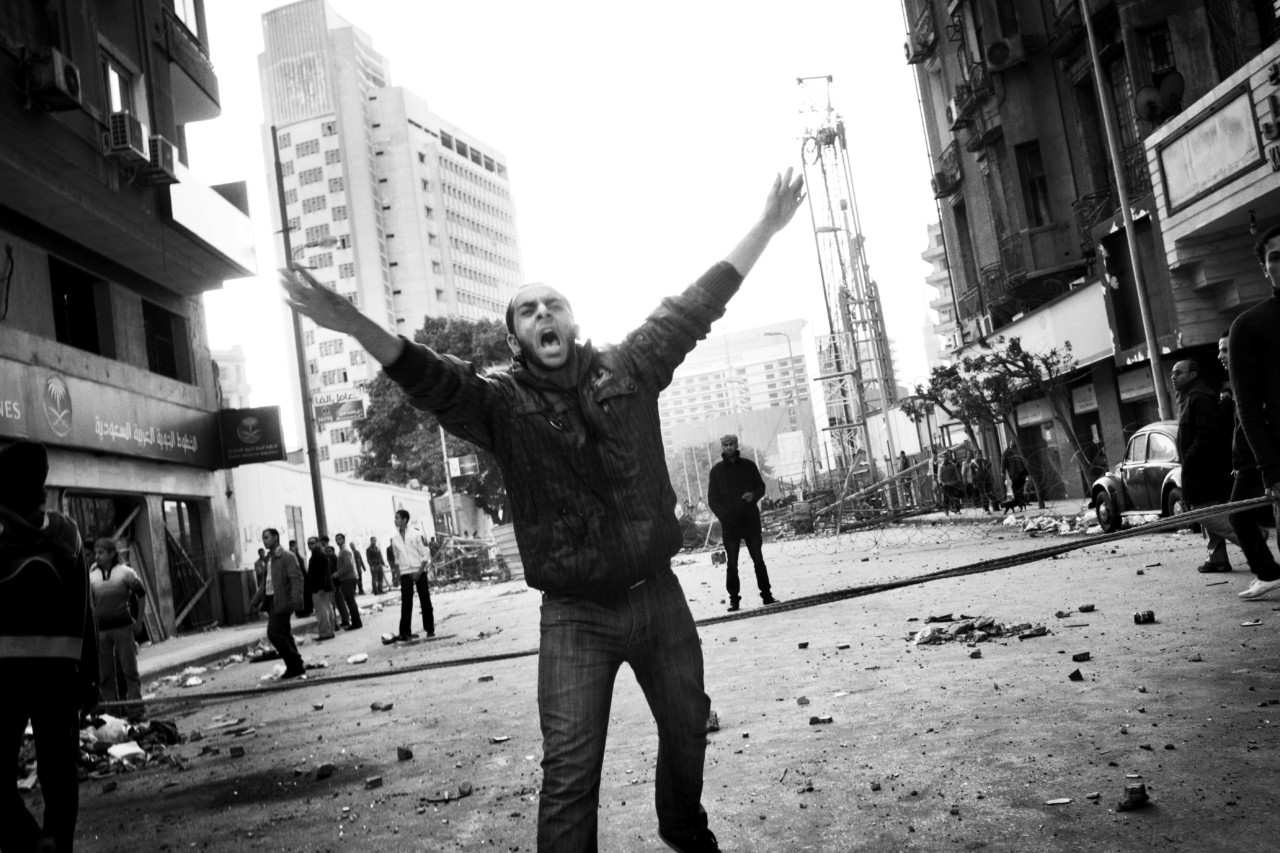

Over the past two decades Magnum’s Paolo Pellegrin has undertaken an extensive exploration of the Middle East, tracing the origins of the Arab Spring to the wider migrant crisis, working both solo and with long-time collaborator, the writer Scott Anderson. This historic piece of long-form journalism is the pinnacle one of the core aspects of what Magnum does. Fellow Magnum photographer Jérôme Sessini explained it succinctly when he said, “Paolo’s long form is the perfect demonstration of what Magnum is. Whenever I feel doubts about my photography, about the sense of my work, this kind of unique work brings me back to reality, leaving aside personal and egoistic questionings to go to the essence of photography, which to me, is about to telling other people about life. Not my own life.”

Here, we speak to Paolo Pellegrin, who gives his perspective on the Middle East and his account of his magnum opus.

A Photographer’s Perspective into a Complex Situation

Having worked in the Middle East intensively, Pellegrin is able to share some insights into the complex situation, one element being the rise, and subsequent weakening of the Islamic State. That they may be losing their grip is not straightforwardly a cause for celebration – “It doesn’t really mean that they are less dangerous,” says Pellegrin. As a result, ISIS has become more chaotic and violent in randomised attacks. “The more they lose ground in Syria and in Iraq, the more they revert to terror. When I was in Iraq last month, ISIS had just lost Fallujah the week before and there were a number of attacks in Baghdad. They want to reassert their presence, to show that they are strong. I think it will take generations to find a solution. It’s not a battle where anybody wins their territory on the ground.”

“This is a macroscopic set of ongoing events, and it’s reshaping a large part of the world, not only in terms of refugees or terror, but in every sense – politically, socially, and culturally. For the large part, Iraq and Syria are modern creations of former colonial powers, which created, in an arbitrary way, these places which didn’t really exist naturally because they put together Shiites and Sunnis, and Kurds with Arabs. In a sense, it’s a recipe for what we’re seeing now. The seed was planted a long time ago. What’s interesting is they’re readjusting to what what the situation was before the English treaties created modern Iraq, for example, they seem to be redividing according to sectarian lines.”

Individuals as Symbols of a Wider Situation

Pellegrin and the writer Scott Anderson agreed that their approach should be to focus on a number of individual stories, revisiting those individuals and exploring their stories in depth. “Scott has this way of spending time and going in depth,” explains Pellegrin. Through this approach, the duo relayed the stories of several individuals, including Azar, a Kurdish doctor on leave to battle ISIS, with whom Pellegrin spent the most time and still keeps in touch with, and Wakaz, a former day laborer who was recruited by ISIS. Wakaz was interviewed while being held prisoner by the Kurds in northern Iraq and so Pellegrin and Anderson didn’t spend as much time with him as they did with the others, with whom they revisited repeatedly, adding depth to their stories.

The benefits of telling stories through the accounts of real characters, according to Pellegrin, are two fold: on one level there is a visceral emotive response to the human tales, and in a wider context, their stories become emblematic of an issue that affects the entire world. “These stories could reflect and help the understanding of the larger story, so, in a sense, they become metaphors of the larger story,” says Pellegrin. “The history in the Middle East is so complicated that telling it could become a very academic exercise, so the fact these people have such compelling stories helps the viewer or reader to understand it from a human standpoint.”

The Power of a Single Image

“This is a family that were escaping from Southern Lebanon, which was being bombed very heavily by the Israeli defence forces. I was in a town called Tyre and saw these vehicles appear – they were all fleeing. This particular car stopped for a moment and I bent and took this frame. This picture does something that I’m always interested in – something that photography can do, which I find quite powerful – to have a tension between the moment and also having an echo to a condition, something larger. This young girl in the picture is looking outwardly but she’s in some mental space looking somewhere; it’s about her in that moment, but it also speaks about being a refugee, about the condition of refugeeship, and in that sense I find it quite effective, because it touches these two points: the micro and the macro. When photography does that it can be quite powerful.”

On Commitment to Photojournalism

In the nigh-on twenty years that Paolo Pellegrin has spent working in the live conflict zones of the Middle East he has, expectedly, had to navigate some very dangerous situations. In Lebanon in 2006 he and Anderson were spared when an Israeli missile missed the pair by just meters; both were hit by shrapnel. For this specific project, the pair were very cautious about their movements, carefully preparing for trips and planning their movements. When asked about his motivations for putting himself in such high-risk situations for the purposes of photojournalism, Pellegrin is introspective: “I mean, this is a question for myself also,” he muses, “and for all the photographers who do this, even more so now because I’m a father of two young girls. This obviously completely changes the nature of the experience. My responsibilities and place in the universe have been modified.”

“Why do I do it? However imperfect the whole media world might be, I still think it’s extremely important that stories are told – and I say this as a maker of images and as a reader. If there are no journalists – if there are no writers, photographers, videographers – who go out there as witnesses, especially doing this long form of journalism, as society, we lose out enormously because you can’t always rely on news cycles. I think for a better, deeper understanding it needs this type of commitment.”

Pairing With a Writer

The practice of a photojournalist working in tandem with a writer on long-form investigative piece was one of the foundations of the early work of the fledgling Magnum agency in post-war Europe. One of the first instances of such a double act was Magnum co-founder Robert Capa working with writer John Steinbeck on an exploration of the then very mysterious Soviet Union, publishing A Russian Journal, a portrait of the USSR in the early Cold War years in 1948. Seven decades later, and Pellegrin’s in-depth study of the Arab world with writer Scott Anderson – with whom he has worked for 20 years since being paired by him by the New York Times in 1996/97 – also follows this model, taking a similarly long-form approach to the telling of a story; a slow yet thorough antidote to the fast media, rolling-news generation.

“This is the type of long-form, in-depth type of journalism that I’ve always wanted to do,” says Pellegrin, reflecting on his work. “Scott [Anderson] has this perspective on history, of taking a step back and looking at things from a slightly different point of view. He doesn’t necessarily chase news; he’s always trying to connect to a larger picture. I find myself very in tune with that idea. Over the years, we have seen so many things together, and with conflict and war, it’s important to work with somebody who is not only your friend but that you respect deeply and with whom you share core values.”

Over the past two years, Paolo Pellegrin and Scott Anderson have created a comprehensive document that unpicks the conflict in the Middle East, ruminating on its possible causes and looking outwardly at the rippling effects it has had on the wider world. This exceptional body of work was recently published in a dedicated issue of the New York Times Magazine, featuring just their work and only one singular advert – for the Pulitzer Center that supported the project.