Devastation and Restoration in Notre-Dame de Paris, One Year On

Patrick Zachmann photographed the fire that swept through the landmark last year and continues documenting the ongoing efforts to secure and renovate the site

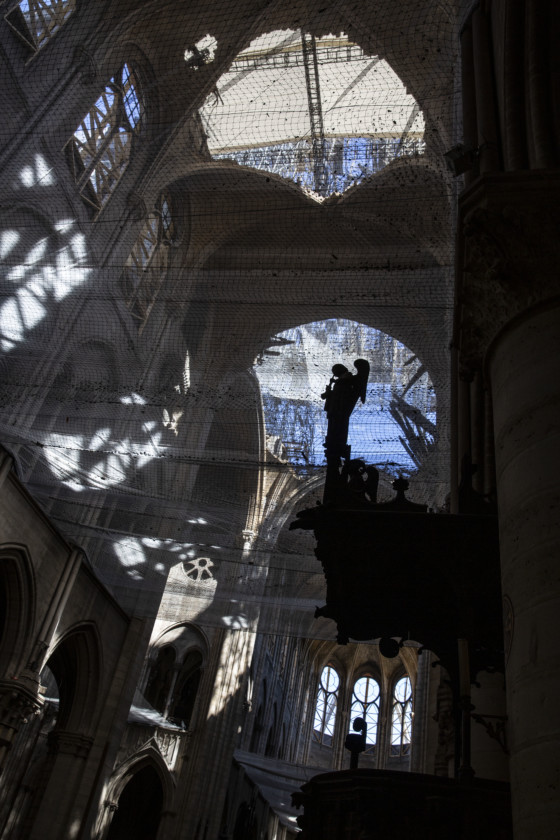

On the evening of April 15, 2019, at 6.18pm a fire broke out in the attic of Notre-Dame, Paris’ famous cathedral which traces its origins to the 12th Century. The fire spread through the ancient, soft timbers of the roof, which had been earmarked for restoration in 2015, and by just after 7pm, flames broke through the exterior becoming visible to crowds gathered nearby. Over 400 firefighters combatted the blaze, which lasted 15 hours. The fire left most of the wood-and-metal-built roof destroyed, as well as the spire which had collapsed at 7.50pm. Fortunately, the majority of the cathedral’s interior was protected by the strong stone interior of the nave, the vaulting of which kept much of the heat and damage outside the building.

Magnum photographer Patrick Zachmann – a Paris resident – photographed the fire as it started and tracked its progression through the building. He went on to gain access to the extensive, and at times perilous renovation work that continues today. His work from the project has been published in TIME, Stern Magazin, Le Figaro, Le Monde, Libération, L’Obs, De Standaard and others.

Today, a year into his charting the work, we discuss the project, its challenges, rewards, and the place that Notre-Dame plays in the communal memory of Paris.

You found yourself well situated to cover the fire itself, being in Paris, but what made you wish to continue documenting the efforts in the months that followed, and did you know from the outset that this would become a long-term project?

Being in front of the cathedral on the 15th of April and witnessing this symbol of Paris burning made a great impression on me: it moved me a lot as a person and as a Parisian citizen. As a photographer, the wish to start and then continue documenting this huge reconstruction project came a bit later, as my interest grew upon getting inside and seeing the reality of the damage. Curiosity and the will to make my own opinions always drove me forward and photojournalism is all about that, I guess.

I am sometimes slow to commit myself to a new subject because I know that generally it will last weeks, months or even years. Therefore, I need to be sure that I will be willing to do it in the long-term, and also that the subject has a connection with my core concerns – in that way I can project myself into it. In the case of Notre-Dame, it took me a couple of weeks before I made up my mind and started to approach the Ministry of Culture, which was in charge of the site at that time.

How hard was gaining the access initially?

I talked with Magnum Paris’ Editorial department, especially with Christophe Calais, about this project. We built a document using some pictures from the archive of Notre-Dame that other Magnum photographers had taken in the past, alongside my work including photographs of the fire itself. We also selected pictures from my body of work dealing with memory and identity, as well as my previous reportage on the new excavations in Pompeii. These – alongside evidence of many previous worldwide publications – helped to convince the ministry to grant me access.

"In those earlier days I could be alone and move everywhere in and outside the cathedral. That was a fantastic experience"

-

How did things change over the months to date in terms of your working practice, and the restrictions on the site?

I started to shoot at the end of May, 2019, and stopped at the beginning of August when the site closed because of lead contamination. I have been able to go back since late September and have been the only photographer to be allowed to work. But things changed; the security protocols became harder and harder to work with. They created the “Etablissement Public” led by General Georgelin, directly nominated under the orders of President Macron. He and his Communication Department became our interlocutors. We developed a relationship based on trust and exchange. After that, neither I nor anyone from the media could move alone in the construction site. I now had to be accompanied by a security guard. When I look back at what I could do at the beginning, and think about how I could move so freely, I am really happy to have had the opportunity to take all these pictures. In those earlier days I could be alone and move everywhere in and outside the cathedral. That was a fantastic experience.

It’s safer now, even though the protocol obliges me to wear all kind of protective garments: overalls, security shoes, disposable underwear, gloves, helmet and a respiratory mask. Everything brought into the so-called “polluted” zone must be either thrown away in special plastic bags, or washed under a shower, including ourselves. Consequently, I have to protect my camera and lenses with a plastic bag, and then put the whole thing under the shower. You can imagine how it sometimes is difficult to shoot. But those are the rules. Sometimes my pictures get out of focus because my gloved finger, with the plastic wrapped around my camera, pushes the wrong button!

"In witnessing a part of it burning, being destroyed, I realized how much more this monument is than a church or an extraordinary piece of gothic achievement; it is part of our Parisian identity"

-

Did Notre-Dame already hold a place of focus or personal interest for you, before this?

No, it didn’t. And if I weren’t there the day of the fire, I would not have started this long-term project. I photographed the cathedral only once before – during François Mitterand’s funeral. I don’t think I ever even entered it! I usually am not that interested in religious matters, including art or churches. In addition, I am not a believer in god.

But, you know, you sometimes need to be far away from your home or to have lost something or somebody to realize how it or they were important to you. Regarding Notre-Dame de Paris, it’s the same thing. In witnessing a part of it burning, being destroyed, I realized how much more this monument is than a church or an extraordinary piece of gothic achievement; it is part of our Parisian identity. We need symbols and references to the past and to history. Notre-Dame is one of them.

We covered your work in Pompeii previously – it strikes me that there is a lot of crossover here – do you see shared features in the bodies of work? Perhaps reflecting some deeper interest of yours?

I have, all through my career, been photographing and interesting myself in people. Therefore, it might seem paradoxical that I am focusing now on a monument.

Nevertheless, Notre-Dame is also a fantastic human venture which fits into a history of hundreds of years of human effort and work. An army of archeologists, engineers, architects, historians of art, specialized craftsmen such as carpenters, stone cutters, stained glass restorers, scaffolders and rope technicians—real alpinists!— are on the site every day, motivated, concentrated and proud to participate in this historical enterprise.

Still, we are talking about a monument and these are not my usual source of interest. Apparently… But, in actuality, when we think more deeply, this work is about the disappearance of a patrimonial memory, a part of our collective history. Notre-Dame is a symbol of Paris and part of its identity, for us and for the whole world. I have worked intensively on memories. The memories of immigrants, family memories (or lack thereof), the unspeakable memories of genocides and dictatorships, and what I call ‘the memories of stones’, or Mémoire de pierres – works like this in Notre-Dame or previous works in Pompeii.

In Pompeii, archaeologists were digging out frescos, writings, objects, amphorae…both from the ground, physically, and from the past, in our awareness. They were revealing a memory which disappeared with the eruption of Vesuvius twenty centuries ago.

Here, with Notre-Dame, people are working on making a disappeared memory alive again. From disappearance, comes reappearance. Just as with photography.

"I have worked intensively on memories. The memories of immigrants, family memories (or lack thereof), the unspeakable memories of genocides and dictatorships, and what I call ‘the memories of stones’"

-

Are there issues with repetition over the months on such a small site, or does the developing situation provide ample subjects for images?

This is one of the challenges of this project. Not everything happening on the site is visually interesting. The evolution of the work and its visible effects happen very slowly. Additionally, we had to work around a period of closure because of lead contamination, then the weather – and especially the wind – slowed down a lot the scaffolding work. Then came the strikes, and now the coronavirus, which has forced the closure of the site.

But the main challenge has been to keep my energy and creativity alive even when the difficulties are many. One of those challenges has been to get the right information at the right moment about what would happen in the following days. I often have to ask a lot of people in charge to get this information. The plans change all the time, because of the weather or for security reasons. Fortunately, I’ve developed very good relationships with everyone from top decision-makers to the crane operators or scaffolders. This friendly network obtained with time and confidence helps me a lot. Once again, my long-term experience working in China with the people and culture there taught me patience and humility which are essential in photography in general.

Ultimately I find this project fascinating because it requires creativity and curiosity to avoid repetition, a human dimension which I appreciate a lot, and, at the same time, a journalistic approach to look for information and stories to tell.

"Ultimately I find this project fascinating because it requires creativity and curiosity to avoid repetition, a human dimension which I appreciate a lot"

-

Is making this work oddly like a ‘day job’? Turning up to the same place repeatedly, seeing the same technicians and so on?

I have always been in and out. I like moving to-and-fro, whether that’s in far-away countries, or here in France, where I have developed quite a lot of personal projects. But with time, after forty years of travelling all over the world, I have begun to feel tired of going far away. Maybe it will come back again, but nowadays, I hugely enjoy not having to take planes, make long trips, or being far from home for a long time. I am also currently making films and that requires my time to write. One of them takes place in Naples – which I have found to be a perfect distance!

The irony of this is that, for now, anyway, I don’t have choice: we all are confined at home.