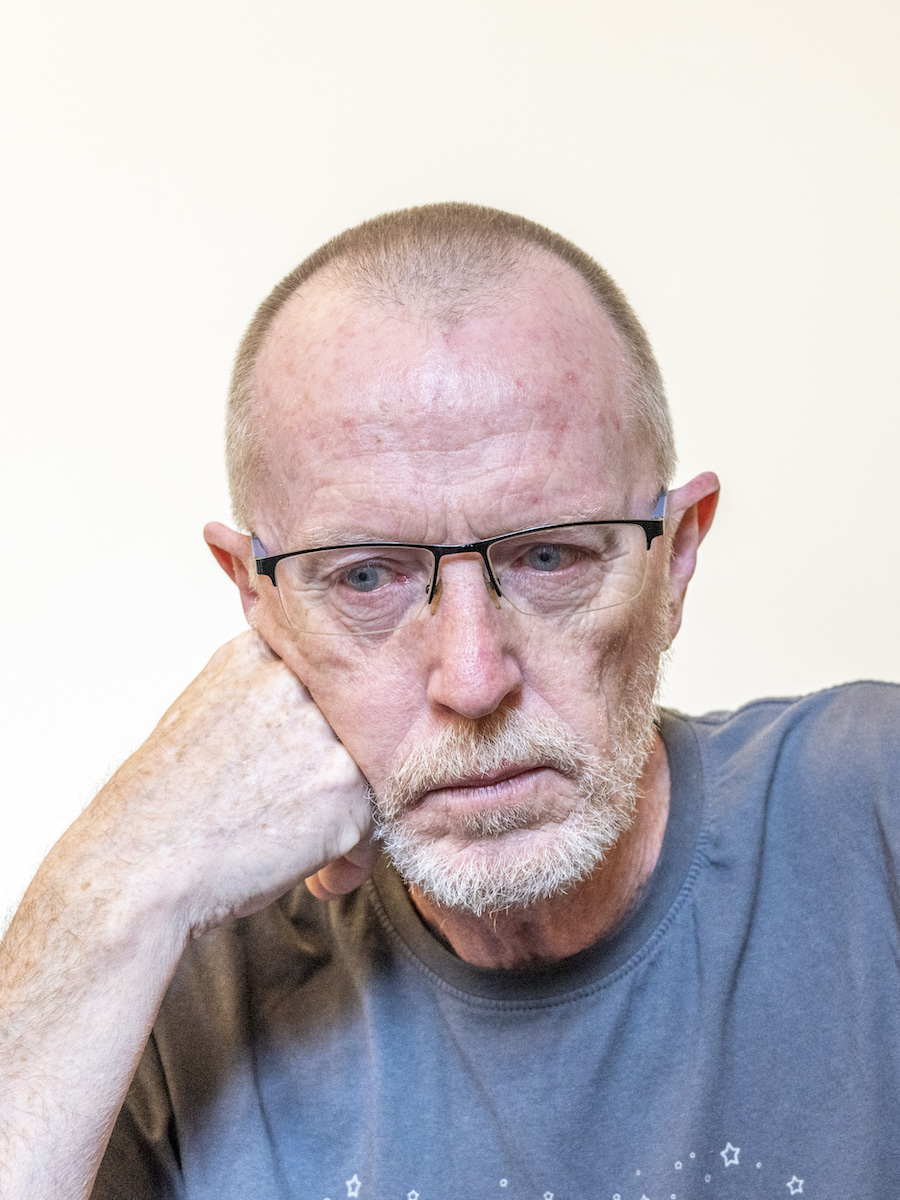

Peter van Agtmael: A Decade of Documenting Israel and Palestine

The photographer shares a selection of images from 2012 to 2023 and a short essay. Warning: this article includes graphic content.

I was drawn to Israel by family and to Palestine through friendship. I’ve been trying to excavate the many layers of the conflict for more than a decade, with many years of work to come. How do you tell the story of an endless war? What are the duties and responsibilities of a journalist in a war that is as much about information as it is bullets and bombs?

A few days after the October 7 attacks, I was standing on top of a hill overlooking Gaza when I was asked for my thoughts by a journalist I’d just met. Not knowing the person or the implication of the question, I responded neutrally, “It’s complicated.” She started shouting at me that Hamas was a bunch of bloodthirsty cowards who provoked the conflict, murdered children and any response by Israel was justified. She said I was a fool and a coward for not immediately acknowledging that.

I’m trying to hold onto more than one truth simultaneously right now, a private act of grieving. My days in the Kibbutzim after October 7 and interviews with survivors and first responders are amongst the most harrowing I’ve seen and heard in decades of covering conflict. Outside a container packed with bodies, an Israeli forensics specialist on the verge of a nervous breakdown described the telltale signs of sexual assault on murdered teenage partygoers. The father of a dead 8-year-old punched the air in an unhinged fit of ecstasy and grief as his sunken, quavering mouth talked about his relief when he discovered his daughter was killed rather than a hostage. A week later, he found out he’d been given the wrong information, that she’s being held hostage after all. In Paris, I passed by a half-torn down picture of her.

In the weeks, now stretching into months, that have followed, I wait every day for news from Gaza. One day it was photos of the ruined garden where I spend evenings when I visit. The parents of a friend lived in an old Ottoman house, and always insisted I join for dinner after the work day was done. We’d chat, surrounded by roses. One day three Hamas guards came by to investigate why I was there. My friend’s father chased them down the street, yelling it was none of their business who he invited over for dinner. Now the house has been destroyed, they have fled south, but are still trapped in Gaza.

Or the story of a former student photographing in a hospital, peering at every screaming bloody face to see if it is one of her sons. Another friend sends a proof of life selfie with his daughters to our group chat when he has internet, growing more haggard and desperate with every message. Most of his days are endless searches for a few drops of water and some scraps of food, thankful for the simple miracle of survival.

Scroll scroll, a Palestinian baby missing half its face is pulled from the rubble, scroll scroll, a Japanese choir sings “Ose shalom” waving Israeli and Japanese flags, scroll scroll, a series of grumpy cats making faces, scroll scroll, a Hamas fighter in a mask rocks a carriage holding a kidnapped Israeli baby, scroll scroll, a recipe for tuna tartare. I’ve had to shut down my social media for my own sanity.

At a moment when every side seems to demand you choose a team or take a loyalty oath, I am continuing my deliberate approach. We get nowhere but deeper into the mess of our own rage and grief by dehumanizing people. What are we so afraid of?

Yet in the images of the violence we are also reminded of the asymmetrical and often indiscriminate nature of the conflict. So far, there are more than 1,200 dead Israelis, and at least 14,000 dead Palestinians.

When you care about people on both sides, there aren’t many people to talk to and everyone seems to think you are a traitor. But I’m not sure there was ever real peace without compromise and understanding, so I hold onto my beliefs, born from two decades of covering war. The truth of my convictions has come from them being tested, again and again. In response to these challenges, they strengthen, shift, or weaken. I believe there is little strength to a conviction that cannot withstand complexity or counterevidence.

One thing is very clear — the role of the professional photojournalist is much diminished. The witnesses, the perpetrators and the survivors with camera phones now dominate the making of the first draft of history, and it has been this way for some time.

When made by the offenders, the propaganda acts as both evidence and a crude and violent form of intimidation. But when the horrors are seen by innocents caught in the middle who have the fortitude to keep filming (and it is almost always video), their record is often the only document of the raw disasters of war, unfiltered by the sensibilities of the media.

For myself, I’m trying to use the stories and emotions of reporting in the field alongside rigorous critical thinking to scrutinize history and the present and make a more rounded and measured understanding. It seems a very modest and perhaps futile act in the face of so much madness and grief, but one always worth attempting. I’m trying to see clearly with deep feeling and a minimum of hatred. It can be a struggle.

Meanwhile the cycle of violence continues, with no end in sight. I always try to think about what might be next, but now I’m afraid of my thoughts.

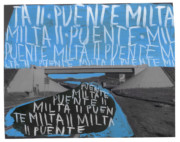

Three Voices From Palestine Curated by Myriam Boulos

From the Archive: Israel and Palestine