Peter van Agtmael on Witnessing the Storming of the US Capitol

The photographer speaks about the precedents and the far-reaching implications of the events of January 6, when Trump supporters rallied at - and ultimately broke into - the US Capitol

On January 6 Peter van Agtmael was on assignment for TIME magazine in Washington DC, photographing the pro-Trump rally that ultimately led to protesters breaching Capitol security, and invading the building itself. Here, van Agtmael speaks with Fred Ritchin – Dean Emeritus of School at the International Center of Photography (ICP) – about the events, historical parallels, the future of photojournalism, and the continuing fracturing of American society. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You can see the TIME feature at the link here.

Fred Ritchin: I know you’re a student of American history, and what interested me was — what were you thinking about while you were photographing the events at the Capitol in Washington yesterday? What came to your mind? Did you have comparisons? What did you think you were witnessing in American history?

Peter van Agtmael: I guess the surreal part of that on so many levels was that there was no direct comparison to anything in recent American history that I can think of. I think that the last time that the Capitol was breached – or something of that magnitude occurred – was during the war of 1812, if I recall correctly.

The comparisons I was thinking about I suppose a little bit were the most recent ones. I was thinking a little bit in my head, especially as I found I couldn’t get in, of Stanley Greene’s pictures from the storming of the Russian White House in the early 1990s.

But I guess more specifically it was a shocking event to witness. At the same time, I think as many people have been pointing out also, not shocking at all given the last few months. Something like this was an inevitability, and it became increasingly clear as the morning and early afternoon wore on.

What was shocking was when I arrived at the Capitol with the first wave of rioters and saw that the police presence was entirely inadequate. There was absolutely no way they were going to hold back this tide of people.

But you’ve worked a lot with the military, and on post-911 America. You’ve worked a lot on these divisions in the country, the splitting into factions. So is this in a continuum from all the work you’ve done before, or is this a jumping into some new territory?

It’s certainly part of a continuum so far as what these groups represent, or aspects of this country that I’ve been documenting for the last 15 years. I think the question that I asked myself that everyone asks themselves is, what era of history is this falling into? Is this the end of one thing and the beginning of another? Is it a continuation of something? Is it the beginning of a whole new era? It’s hard to place precisely in historical terms what this moment is going to mean and represent.

You shot your images outside the Capitol, not inside. What were you hearing from people or seeing outside of your photos, outside the frame, that surprised you or interested you?

There were a lot of strange moments, as you could imagine. The reason I didn’t make it into the Capitol was there was a pretty narrow window of time that I missed. Because, essentially, I left the area where people eventually breached because I was worried someone was going to beat the shit out of me — someone who was harassing me. And I’ve been beaten badly by a mob before, at the revolution in Egypt, and I really didn’t want to repeat that experience. I learned a lesson and if it meant not going in, that was okay by me. Though I’m still kicking myself, frankly.

But it was collection of surreal things. In a weird way, maybe because my brain’s having trouble processing the enormity of the event, the absurd scenario that still comes up is that as the mob was pounding on the doors, and flooding the Capitol, and sending the police packing, there was a guy who stopped to complain about how dangerous a broken flagstone on the Capitol grounds was. And he made kind of a big scene about that flagstone and how dangerous it was, while he was part of a mob protesting the Capitol.

So there’s all these little fragments of memories. There was a guy riding around on a motorized scooter playing the klaxon sound from a movie called ‘The Purge’, the premise of which is that one day each year murder is legal, and a klaxon signals that beginning of that day. And this guy was speeding all around on [the scooter making] that eerie kind of sound.

So what else? Trump and his surrogates have become extremely good at slogans: three-syllable slogans I guess it is. And so there was a lot of that, a lot of the yelling — “Stop the steal.” And a lot of, “This is our house.” “This is the people’s house.” “We have every right to do this.” “This is a revolution.” I heard a few people calling for civil war.

It was very noteworthy how clearly quite well organized this attempt was. When I first got to the Capitol there were dozens of people, seemingly coordinated, with megaphones, exhorting people forward. And especially robust men, especially people that had PPE of different sorts with them to withstand the tear gas and pepper spray, putting barricades up. It all seemed to have been considered.

What also stunned me was simply the lack of presence of Capitol police, a pitiful presence. And I’ve seen far more police for far less protestors at the Black Lives Matter protests I went to last year. And simultaneous with that is the extraordinary lack of force employed by them. I did not witness a single arrest, and I saw hundreds of arrests in the BLM protests. So that’s striking. I think that there will be conclusions drawn about the significance of that certainly.

What kind of image do you see as symbolizing what happened yesterday? What kind of juxtapositions, what kind of moments? Was it about the violence? Was it about the craziness? What was it that was emblematic of what happened yesterday, in your mind?

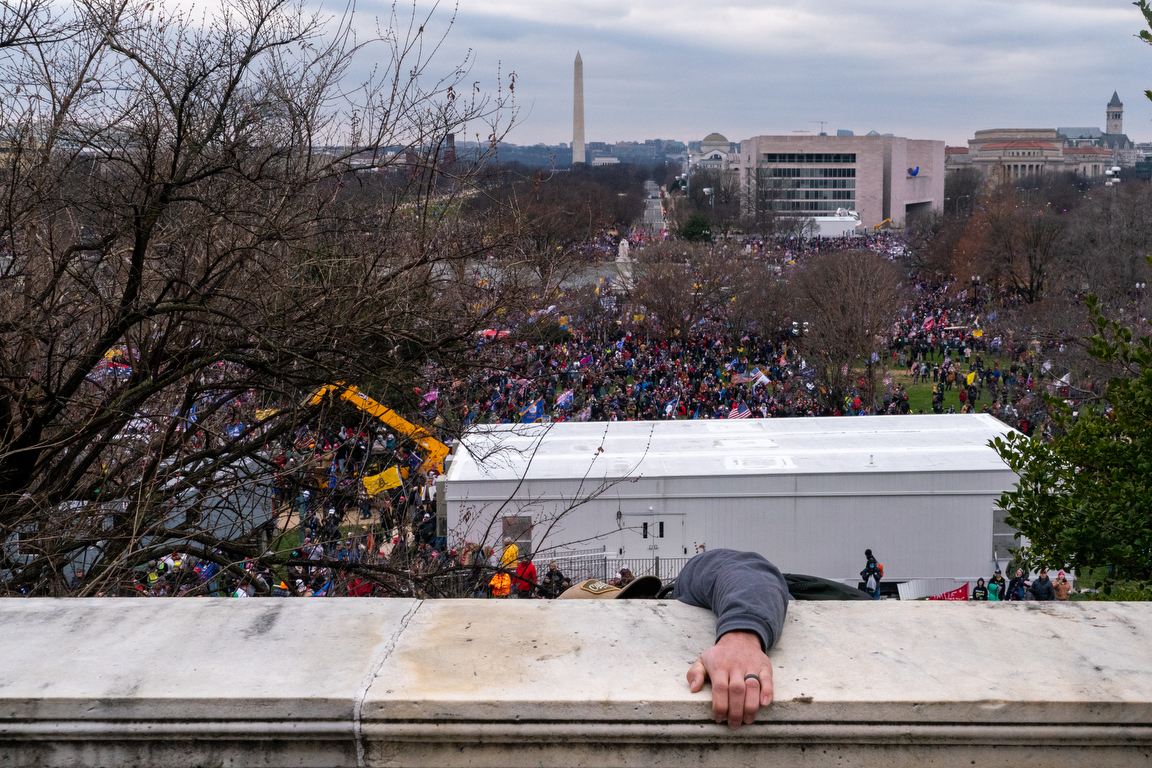

In terms of the images I made, I imagine it’s going to be this picture of just a hand coming over the Capitol wall with this massive crowd and the Washington monument in the background.

Right, that was on Instagram today.

Yeah. So that’s something, especially when it’s at 50 megapixel scale. Right now to me it’s really resonating. Who knows if it will resonate with me in six months or nine months, I have no idea. For all I know, I missed the best picture while editing my selection late at night, I have no idea. But that being said, as much as I liked that picture and I’m glad I was there, I would imagine that the iconic pictures, of course, will be the ones taken inside.

Yeah. But your picture invokes a surrealism that you started talking about at the beginning. The way you saw this, it’s surreal.

Yeah. I probably took the picture I was supposed to take, and that’s fine by me. It’s moments like this that I’m damn proud to be a photojournalist. And to see the just amazing, courageous work that so many colleagues are doing. I mean that very sincerely. I thought it was an amazing moment for journalism in many ways.

But what struck me so far [in terms of images] is certainly the guns drawn and the barricaded doors on the house floor, with the single face peaking in. That picture, no one’s ever going to forget that one. I bet some of the greatest pictures we haven’t seen yet. I wouldn’t be surprised if the best pictures were taken by freelancers who no one ever heard of, who charged in there when they had the opportunity. So I wouldn’t be surprised if the pictures I’m going to remember most I haven’t seen.

There was a great Reuters picture Leah Millis took of all these flashbangs going off with the Capitol in the background silhouetting the crowd. One of those moments that – no matter what kind of photographer you are – you’re looking for, the kind of epic sweep of things I think, more than the strange little moments. I happened to find this strange little moment that had an epic sweep on some level of it, so I’m satisfied with that. But normally the kinds of things that would attract me in a scene I didn’t see there.

If you were talking to young photographers right now, moving forward [from this week’s events], what would you say people should be photographing in the United States? What do we have to deal with, confront, explore, or push to the forefront? Where do we have to go right now?

I think a lot depends on what form the Far Right takes, moving forward. To my mind, when you get interested in a subject, or when you get interested in current events, it’s important to invest in those things. I think of my own trajectory: my interest in the United States came partly from being an American and someone being interested in history, but initially from covering so-called current events. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan exposed me to part of the nature of this country that I hadn’t experienced before. A part that I may have understood intellectually, but I didn’t understand emotionally. And you only can really invest in something when you understand it emotionally. This is my experience.

But in witnessing these kinds of conflict I wanted to understand, where does it all come from? Which took me to the work that has continued since then, which is looking into ideas of race in this country, and in class, and manifest destiny. And the nature of our empire, and the nationalism, and militarism, the political system. I think to tell any story you have to try and tell it holistically, and that takes time. And that takes a close reading of current events, but a close reading of the history that informs those events.

This country is built on hypocrisy on many levels, and that practice has been controlled by our potent ability to create a narrative. We have so many tools at our disposal to lull our citizenry to an artificial narrative of this century. And that’s a bipartisan effort on many levels. Just the Hollywood nature of so much that happened yesterday shows how far our so-called liberalism goes. Our potent myth creator, Hollywood itself, that sells itself as being so progressive is ultimately the one putting crazy ideas in people’s heads, it seems.

But then, what is the counter-narrative? I think your hand photograph, for example, is part of a counter-narrative. It doesn’t heat it up, it cools it down. It shows the surreal nature of it, the kind of weirdness of it, the bizarreness of it, and it doesn’t fit into a kind of spectacle.

The iconic pictures are really important in serving as kind of symbols. Like symbols and metaphors of history. Where I think a lot of the value from photography comes from is looking deeply at subjects from as many different angles as possible. You make a tangled web that nonetheless has a kind of clarity, specificity, and a point of view, and maybe you’re onto something. I think that the history of photography has also proven that there aren’t that many people necessarily who want to make that investment, in terms of time and complexity.

And I think you’re probably right, I just tend to be envious a little bit of missing stuff. I’ve got FOMO, I guess, wondering about the iconic pictures in there, and wondering what I would have done with [those scenes] had I been inside [the Capitol]. So, I suppose I’ve always seen myself, not necessarily by design, as trying to work around the edges of the iconic, rather than on the iconic itself.

Right. Which is why I think you’re in a very good position to continue to move on. There’s a lot more to be done because we still have no idea who these people are, what they’re about, where they come from. The woman who was killed by a police officer had served 14 years in the Air Force. How did that happen? There’s a lot of questions that are out there and a lot to pursue.

If you look at the woman, the 14-year veteran of the Air Force… there have been veterans ringing the alarm bells for years and years about how vulnerable young soldiers are to being radicalized. And [they’ve said] that these movements are deeply embedded in the armed forces, and are only growing stronger. And I would say, based on my somewhat more-than-casual observations, including fairly in-depth observations of the military over the years, that I would agree with that assessment. I don’t think it’s a total coincidence that the person who was killed was a veteran.

I think a photographer, then, has to somehow ‘get’ that, to show that, to investigate it, to explore that. For us civilians on the outside, we’re not always made aware of these things.

It’s going to be a lot of work, and of course the question is who’s going to pay for it? I wonder about what resources for journalism will look like in the Biden era? We all know that Trump was good for the bottom line. Is that going to continue? Or are already shrinking budgets going to continue to shrink?

On the plus side, we had a moment of reckoning of the way race relates to journalism and photojournalism after the killing of George Floyd, that has created opportunities for the kind of storyteller that might be approaching subjects in a way that’s going to lead to our collective wisdom and enlightenment. So I think there’s some clear opportunities as well.

Is there anything else that you want to add? There are people who have called yesterday, as was said last night by Senator Chuck Schumer, ‘a day in infamy’, comparing it to December 7, 1941 and the attack on Pearl Harbor.

I don’t know, I wonder if Schumer is overstating that. On the magnitude of December 7th or even September 11th, I would tend to doubt it [compares]. I don’t know if this will come across in the right way, but it’s like when you experience something for the first time when you think you’re not vulnerable to these forces… Events can sometimes take on a significance [disproportionate to] what their actual long-term meaning will be.

And I think that honestly these congressmen — they have not felt vulnerable in that way before. So I’ll be honest, I dismiss that statement a little bit.

Like I said, with any event, it oftentimes has less to do with what happened on that day than what follows, and we’ll see what follows.

And what we can do about it.

Yeah, indeed. Good point.