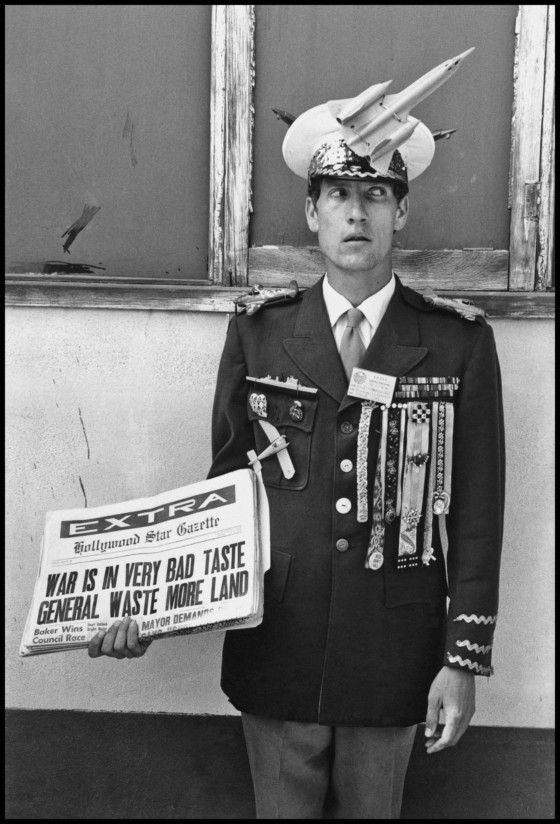

1968: Power, Protest and Politics

Photographs from a tumultuous year of uprisings and unrest

Magnum Photographers

“We have the right, according to our constitution, of freedom of assembly and if you want to hold a meeting for a peaceful purpose to demonstrate, you have that right,” stated American writer and liberal political commentator Gore Vidal during a now legendary television debate with his verbal sparring opponent William F. Buckley in 1968 – a year in which people the world over would assemble in the streets in protest, in solidarity, in revolution and in mourning.

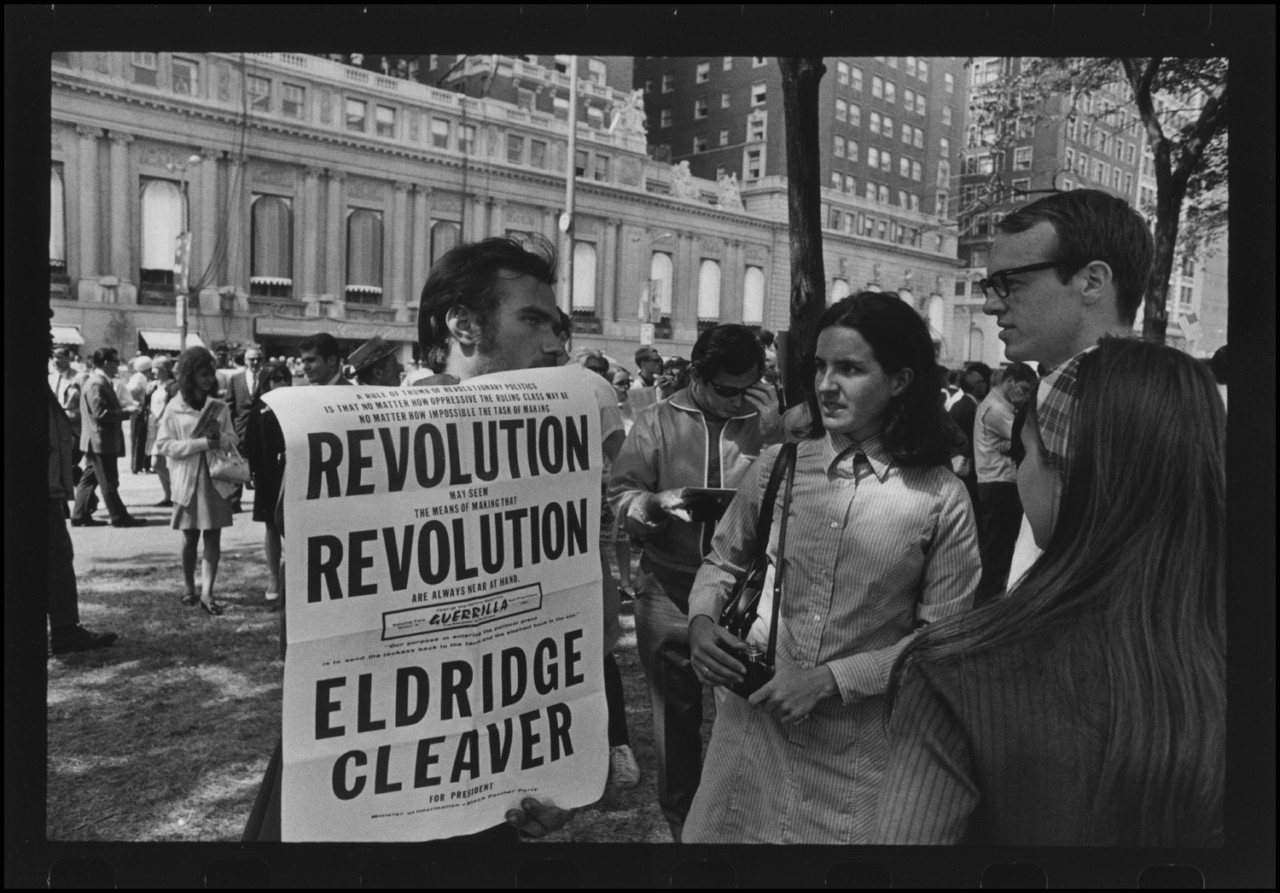

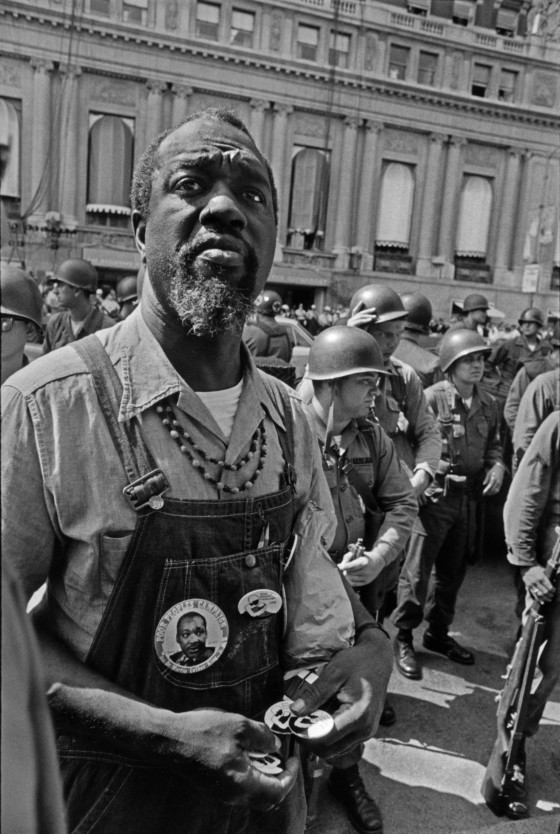

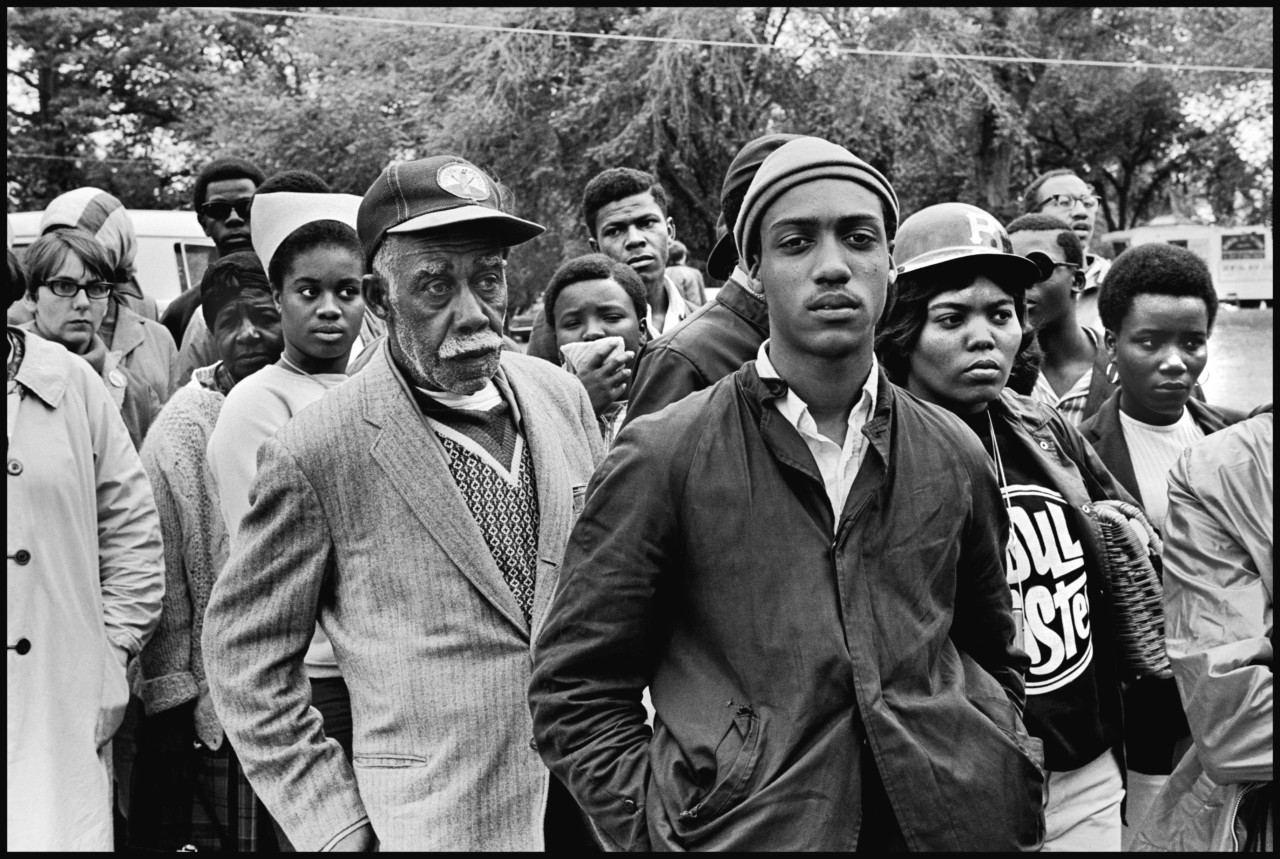

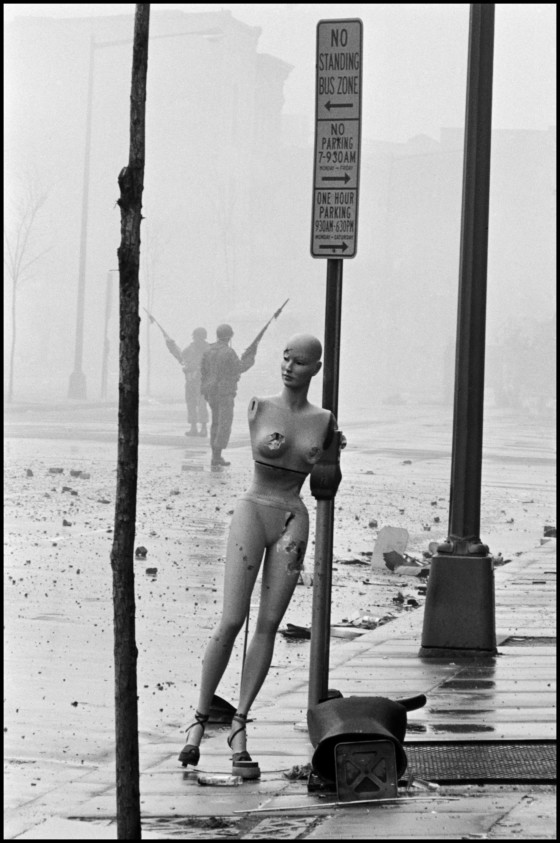

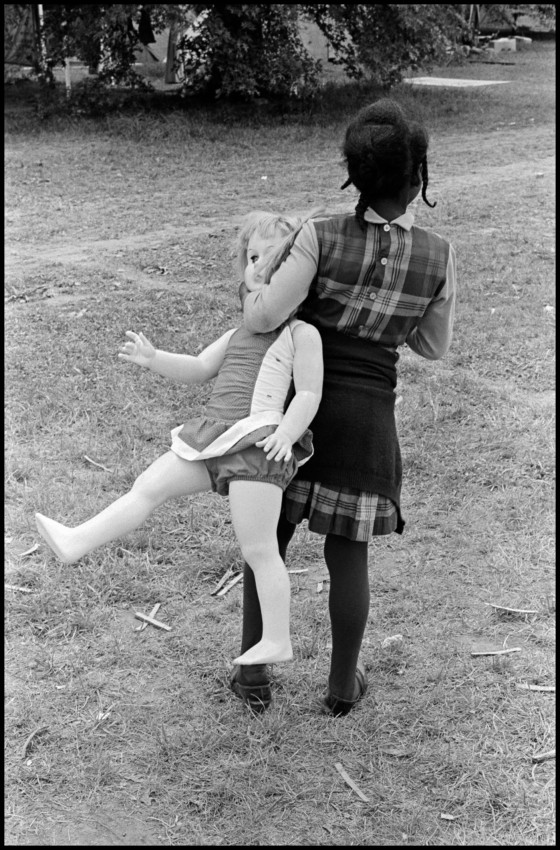

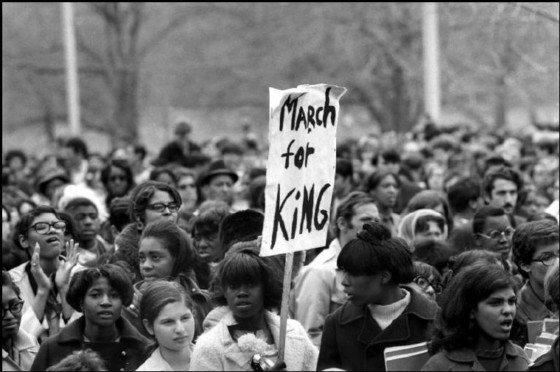

The debate took place at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago (August 26-29) which spilled out into violence as anti-Vietnam War protesters and delegates clashed with police, marking a boiling point in a year of political turbulence and civil unrest. Earlier that year in April, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, prompting protests and riots in over 100 U.S. cities in outrage at his murder, and also to continue to push for civil rights. Raymond Depardon’s images from outside the turbulent DNC conference include a man handing out badges for ‘The Poor People’s Campaign’, himself wearing a large badge for the cause featuring MLK’s portrait. The Poor People’s Campaign itself was initiated by Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to demand economic and human rights for poor Americans of diverse backgrounds.

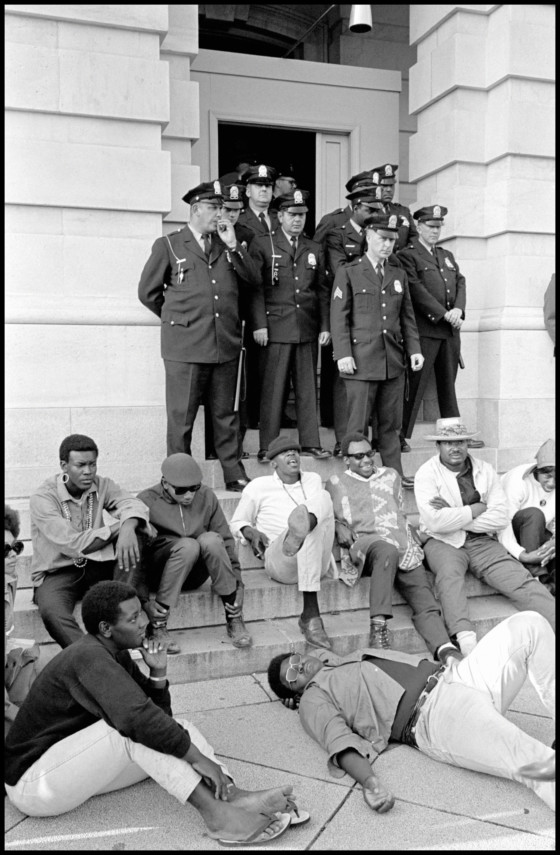

Constantine Manos’s photographs from the Poor People’s March on Washington two months prior depict Rev. Ralph Abernathy, who took the lead of the Campaign following Martin Luther King’s death, and Jesse Jackson from the SCLC, both addressing the crowd. Further afield, Manos photographed youngsters taking part but unable to enter the Capitol as there were only 50 entry passes. They recline in a relaxed manner by the feet of an alert-looking set of policemen.

The night before his assassination, in his ‘Promised Land’ speech, Dr. King reminded people that being disunited only benefited the rich and powerful. He said: “You know, whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favorite, favorite formula for doing it. What was that? He kept the slaves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, something happens in Pharaoh’s court, and he cannot hold the slaves in slavery. When the slaves get together, that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery.” The continuation of the movement he was a figurehead of paid respects to this sentiment.

The assassination of Democratic presidential hopeful Senator Robert F. Kennedy, a high-profile supporter of the civil rights movement and of bringing the Vietnam War to an end, was another blow for the movement. Very much loved by the American populace, RFK once again brought people out into the streets as they paid their respects to the man.

Paul Fusco famously documented the funeral procession as it traveled from New York to Washington D.C. by train. The people who lined the route, standing patiently in the beating June heat, are testament to the affection and respect the citizens of the United States had for the politician, who had once said of public demonstrations of solidarity and protest: “Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

Kennedy had entered the race for the Democratic party’s nomination for presidential candidate in March, and his death left support within the party divided between Senator McCarthy, who ran an anti-war campaign, Vice President Humphrey, who was seen as supporting the status quo of the Johnson presidency, and Senator George McGovern, who had appeal for some Kennedy supporters. The picking of a Democratic candidate would bring up heated debate about the Vietnam War and civil rights, debate which spilled out into the streets surrounding the conference.

Among the protests taking place in Grant Park, Chicago, Raymond Depardon pictured French writer Jean Genet and American writer William S. Burroughs. Genet was on his first trip to America, commissioned by Esquire magazine to cover the convention along with Burroughs despite not being able to legally get into the U.S. due to his criminal record – he wrote Notre Dame des Fleurs (Our Lady of the Flowers) in prison after being convicted of various offences including theft, use of false papers, vagabondage, and lewd acts. Nevertheless, Genet snuck into the U.S. via the Canadian border and produced the essay The Members of the Assembly – A four-day show that ran out of stars.

Burroughs wrote in his report for Esquire: “Regarding conduct of police in clearing Lincoln Park of young people assembled there for the purpose of sleeping in violation of a municipal ordinance: The police acted like vicious guard dogs attacking everyone in sight. I do not ‘protest.’ I am not surprised. The police acted after the manner of their species. The point is why were they not controlled by their handlers? Is there not a municipal ordinance requesting that vicious dogs be muzzled and controlled?”

Authorities in Chicago were primed for clashes, but as a letter sent from the National Mobilization Committee to end the war in Vietnam and the Radical Organizing Committee to members of their organizations points out, some of these preparations may have contributed to a tense atmosphere: “We are sure that you realize that this is a testing time in Chicago. Although our plans are for nonviolent actions and we have made clear for months that we do not desire to obstruct the convention or to interfere with the movement of delegates into or out of the convention, Mayor Daley and the Democratic Party have turned Chicago into an armed camp of national guardsmen, airborne troops on standby, barbed wire, tanks, mace, and every conceivable weapon of intimidation and repression.”

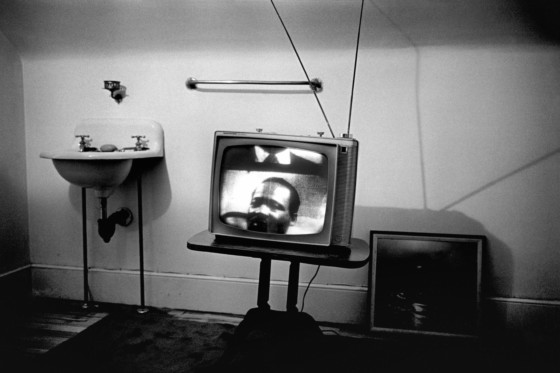

In 1968, the Vietnam War reached a particularly deadly flash point; the Tet Offensive, which began on January 30, resulted in a perceived strategic win for the United States but all sides sustained heavy losses. The images from this time, that were now being published in newspapers and broadcast on television fuelled the anti-war movement and contributed to its acceleration.

Philip Jones Griffiths photographed the war in Vietnam from 1966 to 1971. On the Tet Offensive he wrote: “To the people of South Vietnam and America, Tet 1968 marked the point when the American involvement in Vietnam lost its credibility. To the American people, who had continually believed the ultra-optimistic progress reports on the war, it was the news from Saigon that destroyed their faith in the honesty of their leaders. To the Vietnamese people, caught up in the battles, it was the final disillusionment.”

Anti-war protests spread not only through demographics, counting servicemen and families of men who had been drafted amongst their supporters, but globally, as protests at American Embassies allowed those living internationally to voice their objection. David Hurn’s photographs of one such protest in London depict celebrities lending their high profile to the cause, and capture clashes as tensions between police and protesters erupted into violence.

Reflecting on his work documenting the protest on its 50th anniversary, David Hurn admitted his own cynicism, as he said that he “doubts that any of these marches had much effect at all. There’s more bombs around now than there were then, so in that sense it didn’t make an enormous difference.” However, he was keen to emphasise the importance of being able to exercise such a right, and, moreover, that it can be photographed. “They are incredibly important, because if you’re not allowed to do it, if you’re not allowed to photograph these events, then you know the situation is even worse,” he said.

Witnessing the Japanese student movement, Bruno Barbey was present at the Tokyo protests against the war in Vietnam. he captured the moment protestors clashed with police in the streets of the neon-lit city.

Civil unrest in 1968 was not limited to America. “There has never been a year like 1968, and it is unlikely there will ever be again,” writes Mark Kurlansky in his book, 1968: The Year That Rocked the World (1998). “At a time when nations and cultures were still very different there occurred a spontaneous combustion of rebellious spirits around the world.”

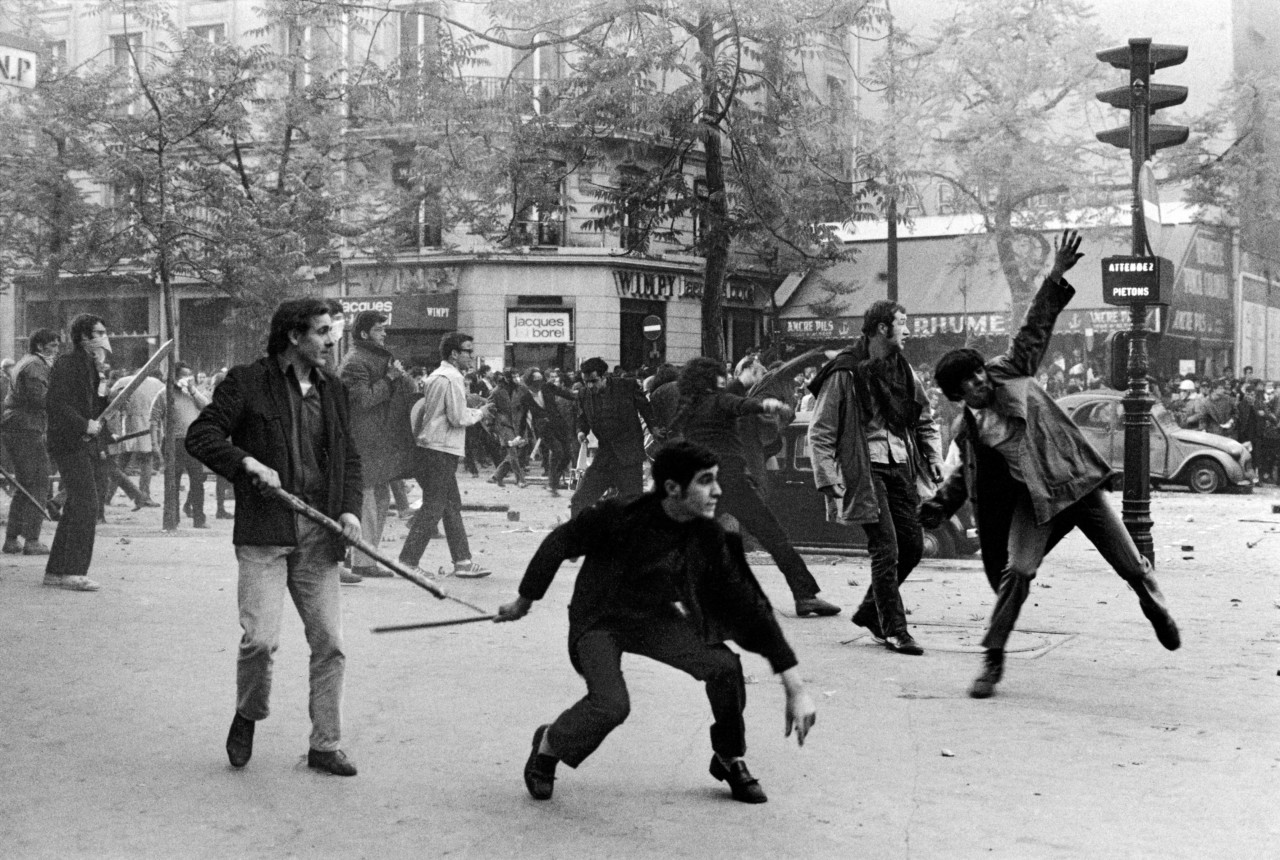

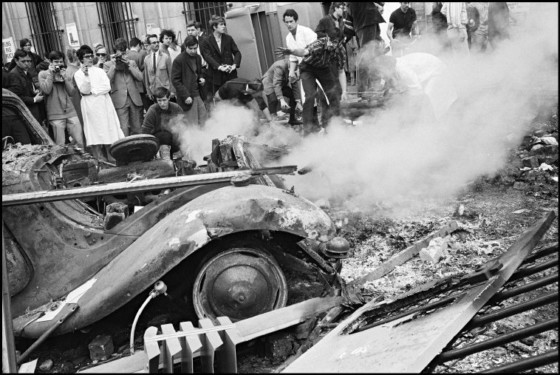

In France, 1968 was a turbulent year politically. Unrest began with a student movement, which was protesting against capitalism, consumerism, American imperialism – including the Vietnam War, and other symbols of order such as traditional institutions. The movement against authority then spread to factories with strikes involving 11 million workers, which lasted for two weeks – the first nationwide wildcat general strike and the largest ever attempted.

Following months of conflict between students and authorities at the Nanterre campus of the University of Paris, the administration shut down the university on May 2. Students at the Sorbonne campus of the University of Paris met on May 3 to protest against the closure and the threatened expulsion of several students at Nanterre. On Monday, May 6, the national student union, the Union Nationale des Étudiants de France (UNEF) and the union of university teachers called a march to protest against the police invasion of La Sorbonne. More than 20,000 students, teachers and supporters marched towards the Sorbonne, still sealed off by the police, who charged, wielding their batons, as soon as the marchers approached. While the crowd dispersed, some began to create barricades out of whatever was at hand, while others threw paving stones, forcing the police to retreat for a time. The police then responded with tear gas and charged the crowd again. Hundreds more students were arrested. Bruno Barbey was present and photographed instances of violence and protest.

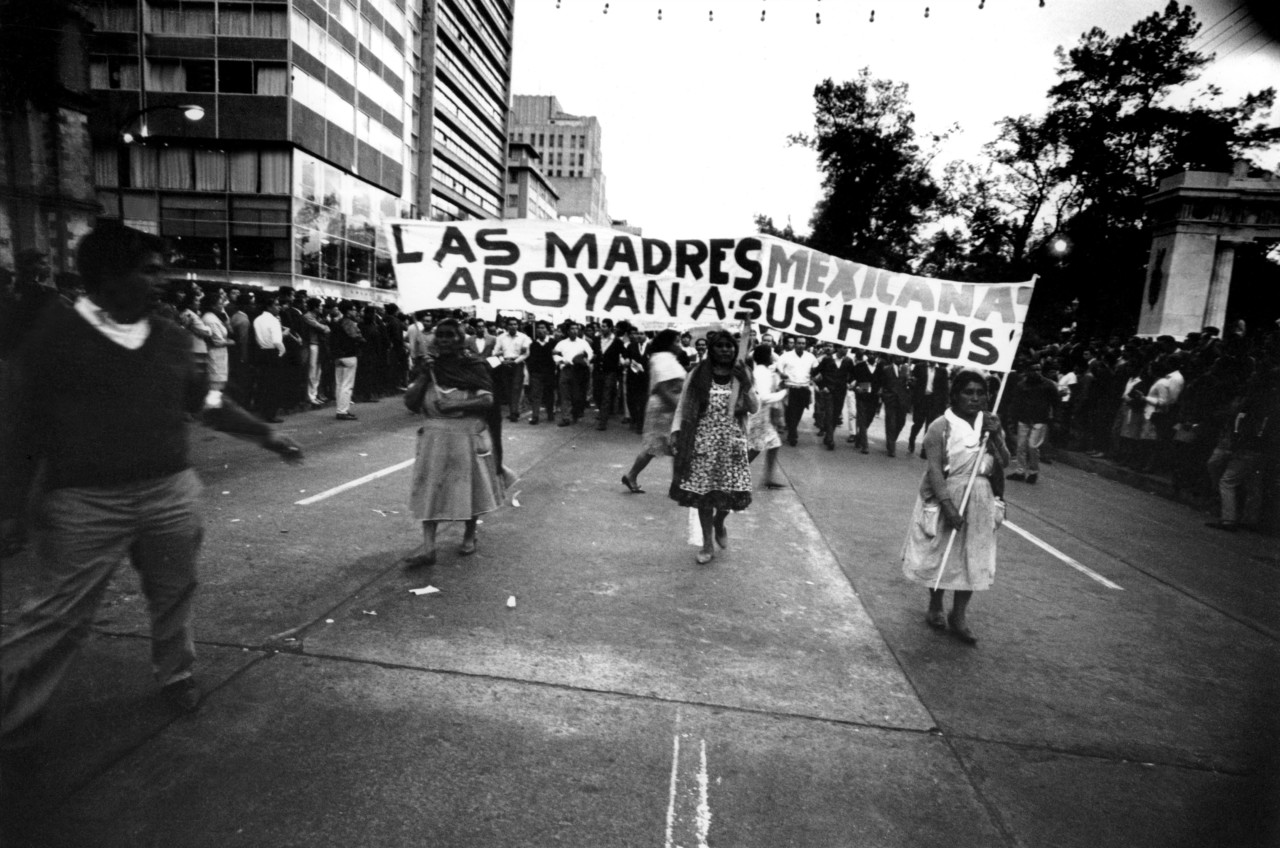

Students were also the driving force behind protests in Mexico, as they rallied behind political reform to the country’s political system in the same year the country aimed to present a positive appearance to the world as it hosted the Olympics. The government cracked down hard on protests and, approximately 10 days before the opening of the Olympics – the first to be hosted by a developing country – student activists were killed by the government during a protest in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City.

At the Olympics, several African-American athletes utilized their platform to protest international and domestic issues back home. During their medal ceremony, U.S. Olympians Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their gloved fists as an expression of solidarity with the civil rights movement in the United States, and American runner Lee Evans accepted his gold medal alongside fellow African-American medalists Larry James and Ron Freeman, also wearing berets in reference to the Black Panther Party, raising their fists in the air.

Speaking about his Olympic act of protest later, John Carlos would say: “The bottom line is, if you stay home, your message stays home with you. If you stand for justice and equality, you have an obligation to find the biggest possible megaphone to let your feelings be known. Don’t let your message be buried and don’t bury yourself.”

The uprising continued elsewhere in the world. For four months in 1968, Czechoslovakia broke free from Soviet rule, allowing freedom of speech and removing some state controls. This period ,now referred to as the Prague Spring, was brought to an end on August 20, when 500,000 Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia. A then 30-year-old Josef Koudelka photographed their arrival and clashes with the people of Prague. He originally published these photographs under the initials P. P. (Prague Photographer) for fear of reprisals. In 1969, he was anonymously awarded the Overseas Press Club’s Robert Capa Gold Medal for those photographs. Koudelka left Czechoslovakia for political asylum in 1970 and shortly thereafter joined Magnum Photos.

“What remains of 1968” wrote Marc Weitzmann in an essay published in the book Magnum Throughout the World (1998), “is not so much the answers that were proclaimed with such certainty but the questions, many of which still present themselves in precisely the same terms: the plight of the Third World, the race issue in the United States, the future of the French education system – and the necessity for civil disobedience.”

Throughout 2018, Magnum Photos is marking the anniversaries of some of 1968’s milestone events by revisiting the the work of Magnum photographers who documented them.