The Iranian revolution of 1979 marked the advent of a new political era for the country, the ramifications of which were felt across the Muslim world. A popular uprising, driven by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini from exile in France, toppled the US-backed leadership ofMohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. In 1978, the late Magnum photographer Abbas arrived in the country; he charted the unrest as it unfolded.

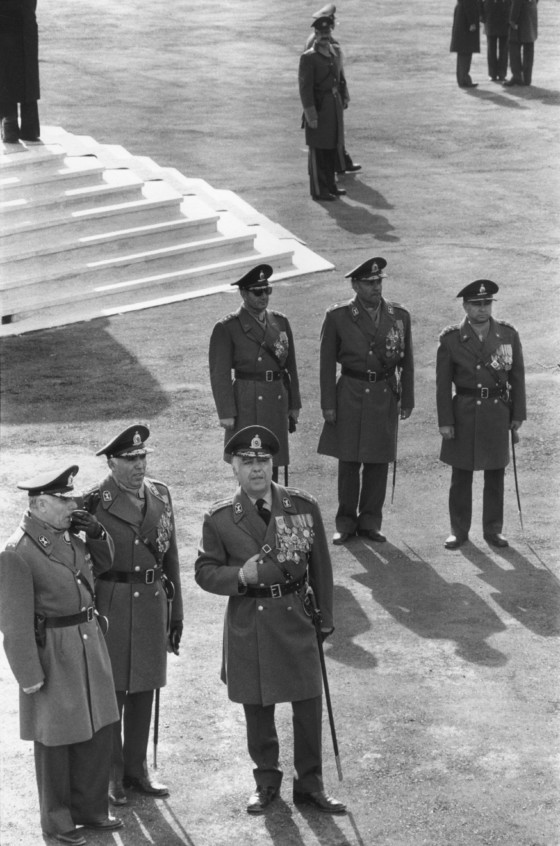

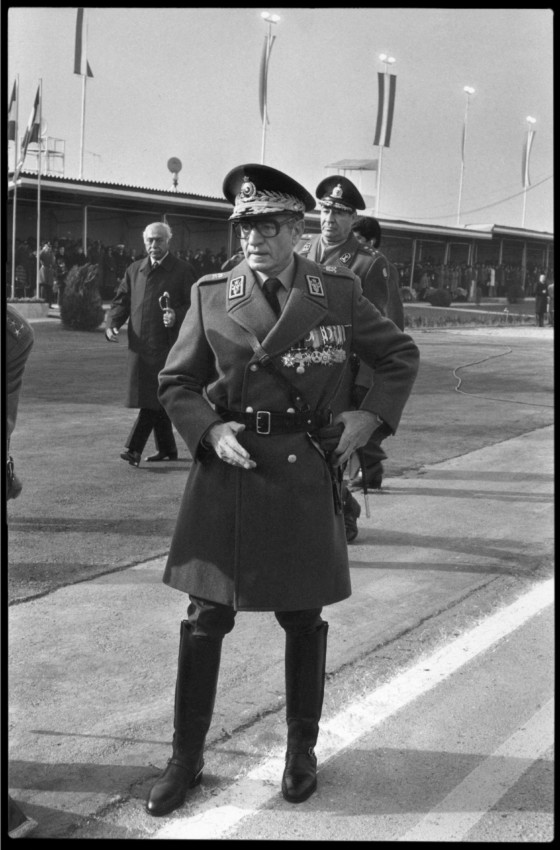

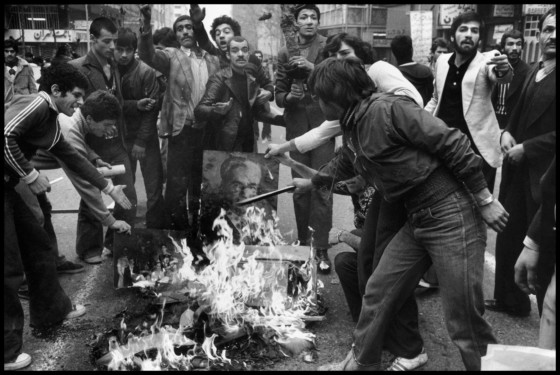

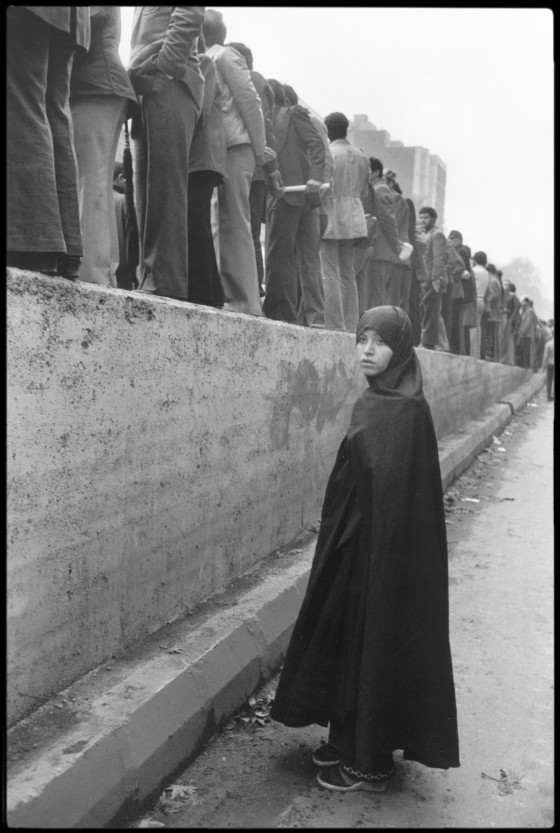

The revolution took the world by surprise. Outwardly, Iran appeared stable: it had an expanding economy and rapidly modernizing infrastructure. But, the reality on the ground was different. The country had undergone a dramatic transformation: once conservative and rural, it was now industrial and urban. For many, too much had changed too quickly and the government had failed to deliver on what it had promised. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi became a symbol of all that was wrong. Along with the Shah’s economic failings, sociopolitical repression had also intensified: censorship, surveillance and torture were common.

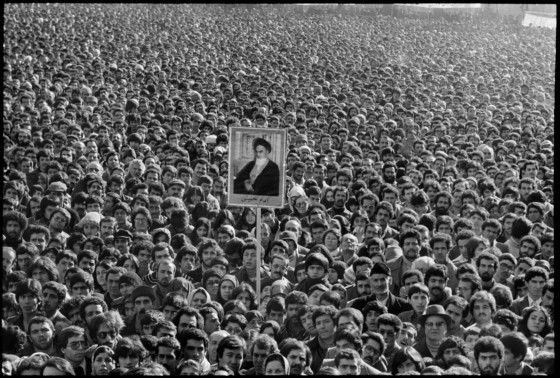

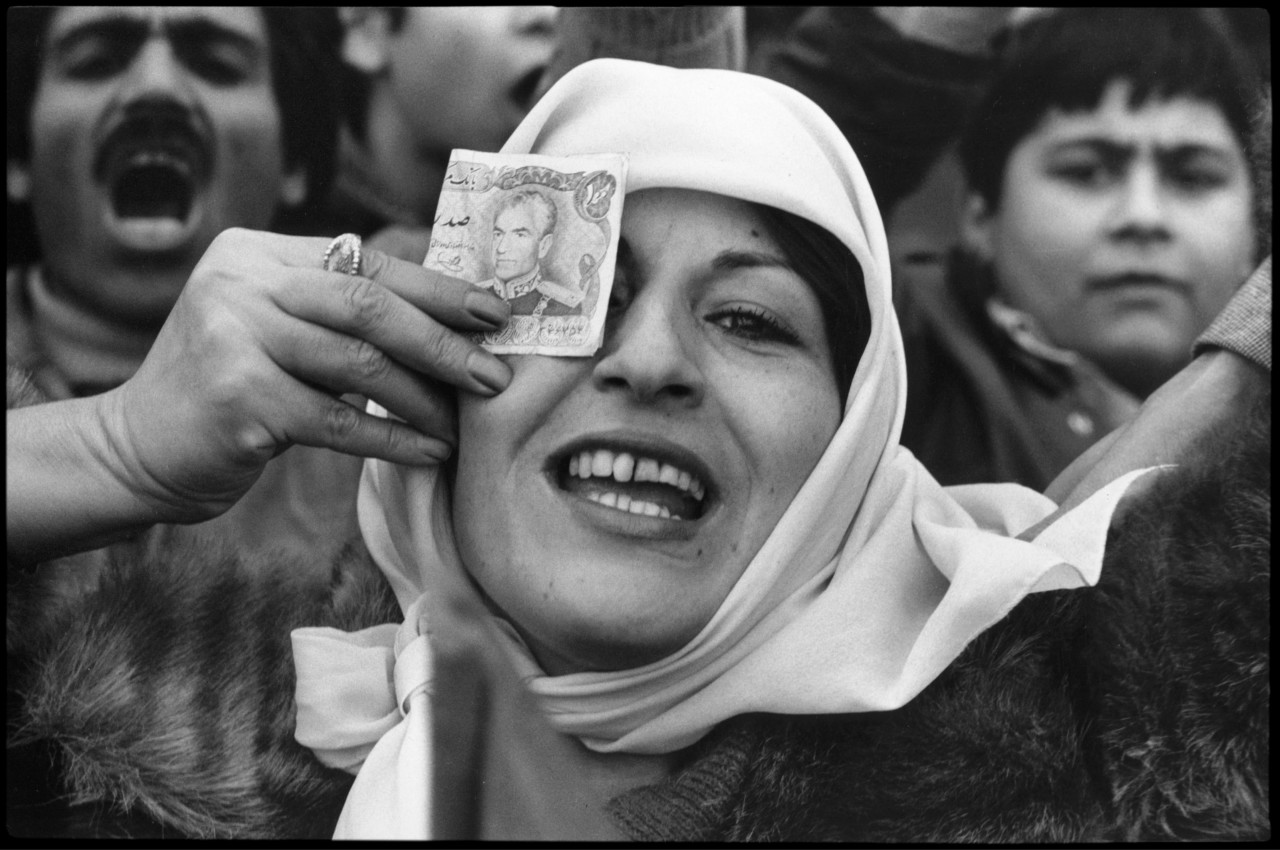

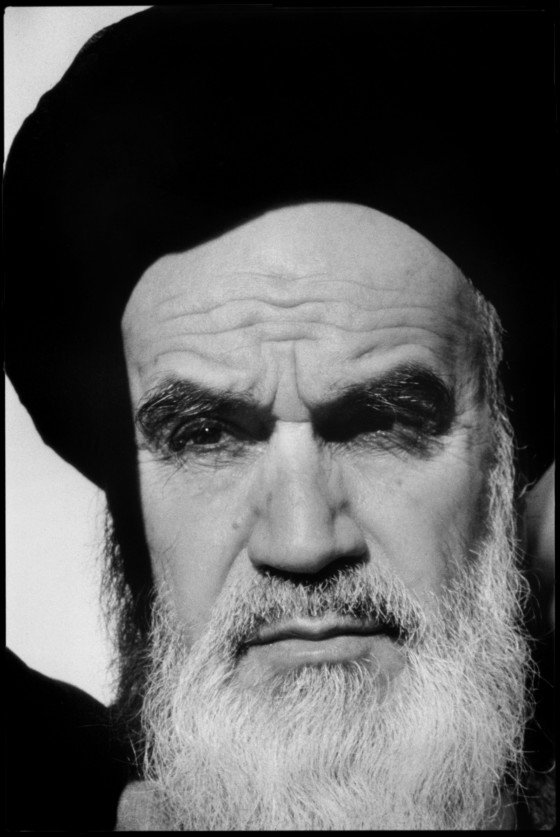

In January 1978, a Tehran newspaper published a front-page editorial disparaging the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The article sparked protests attended by thousands – leftist, Islamist organizations and student movements were all involved. Exiled 15 years earlier, Khomeini was an outspoken critic of the Shah, calling for his overthrow and the establishment of an Islamic republic free from Western control. As opposition to the monarchy intensified so did his influence; from Paris, he set the course of the revolution and maintained its momentum. The relentless demonstrations paralyzed the country; fearful, and weakened by ill-health, the Shah fled Iran on 16 January 1979, assigning control to a regency council and prime minister Shapour Bakhtiar.

Abbas arrived in Iran amidst the growing civil unrest. Iranian-born, the photographer’s family had left for Algeria when he was just eight years old. “I knew, even when it happened, that only once in my lifetime I would be not only concerned but I was also involved, at least in the early stages,” he explained in a 2017 interview with BBC Culture.

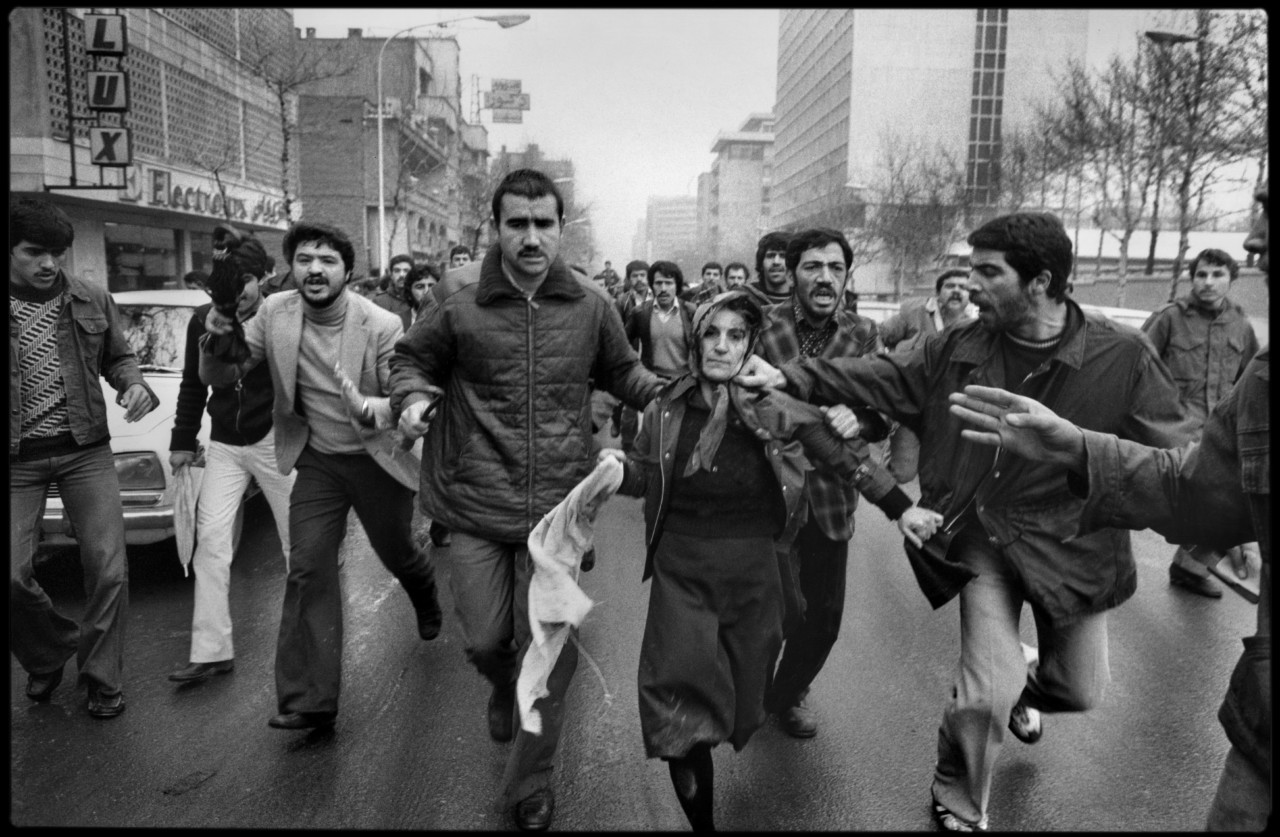

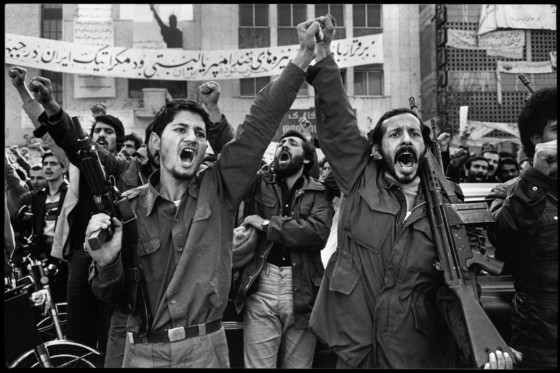

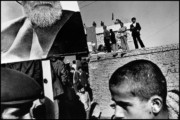

Initially supportive of the revolution, Abbas soon became disillusioned by the violence he was seeing from both sides. “There was a demonstration in favor of Bakhtiar and, of course, the Shah,” recounts Abbas, in the same interview. “Militants gathered around the stadium and started beating up the people coming out.” A dramatic black-and-white image captures a woman surrounded by revolutionaries ready to lynch her. Colleagues and bystanders implored Abbas to dispose of the photograph; to publish it would be to expose the revolution’s darker side. But, he refused. “I am a journalist, which is a historian of the present, so I have to show these pictures now,” he reasoned. “And, in retrospect, I think I was right. If you look at their faces, lots of the violence and the hate, which surfaced later on, during the revolution, is already written there.”

"I am a journalist, which is a historian of the present, so I have to show these pictures now"

- Abbas

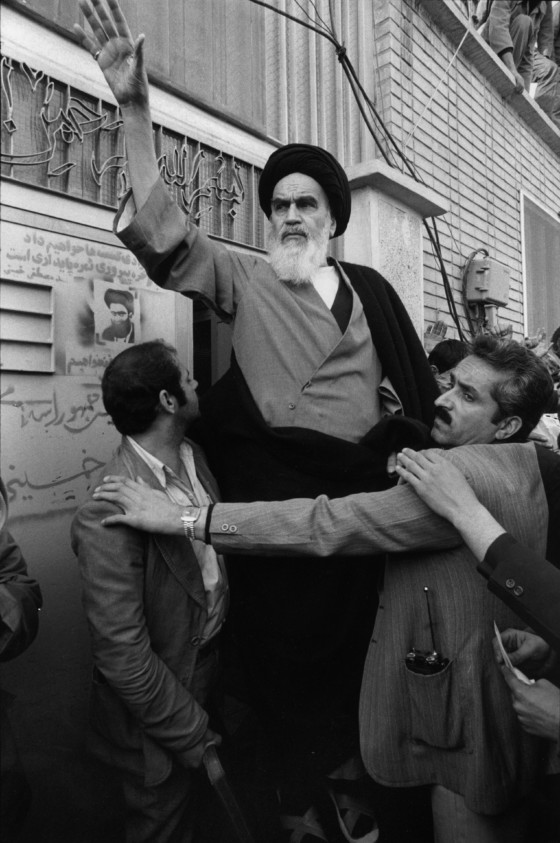

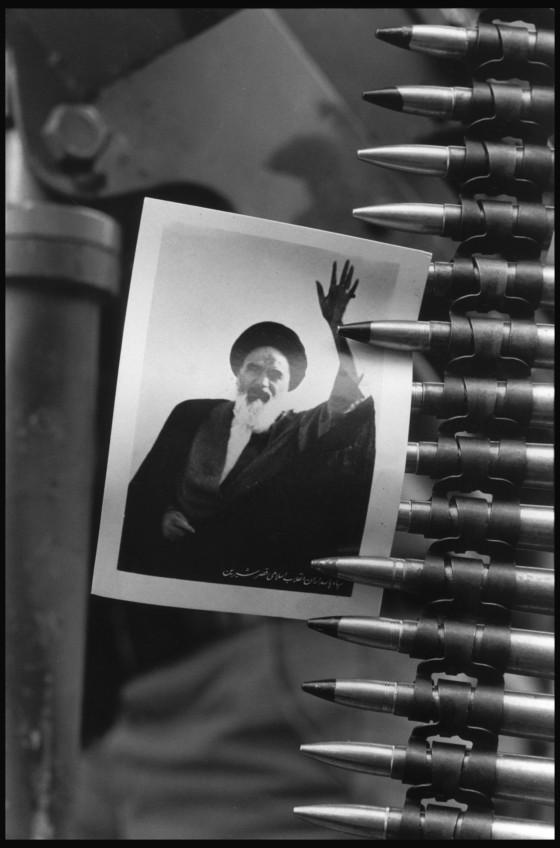

On February 1, 1979, Khomeini returned. With the Shah in exile and Shapour Bakhtiar incapable of recovering control, he was ready to establish an Islamic republic and eliminate the westernization of the country permitted by his predecessors. Ten days later Khomeini was officially brought to power after guerrillas and rebel troops overwhelmed the Shah’s remaining forces.

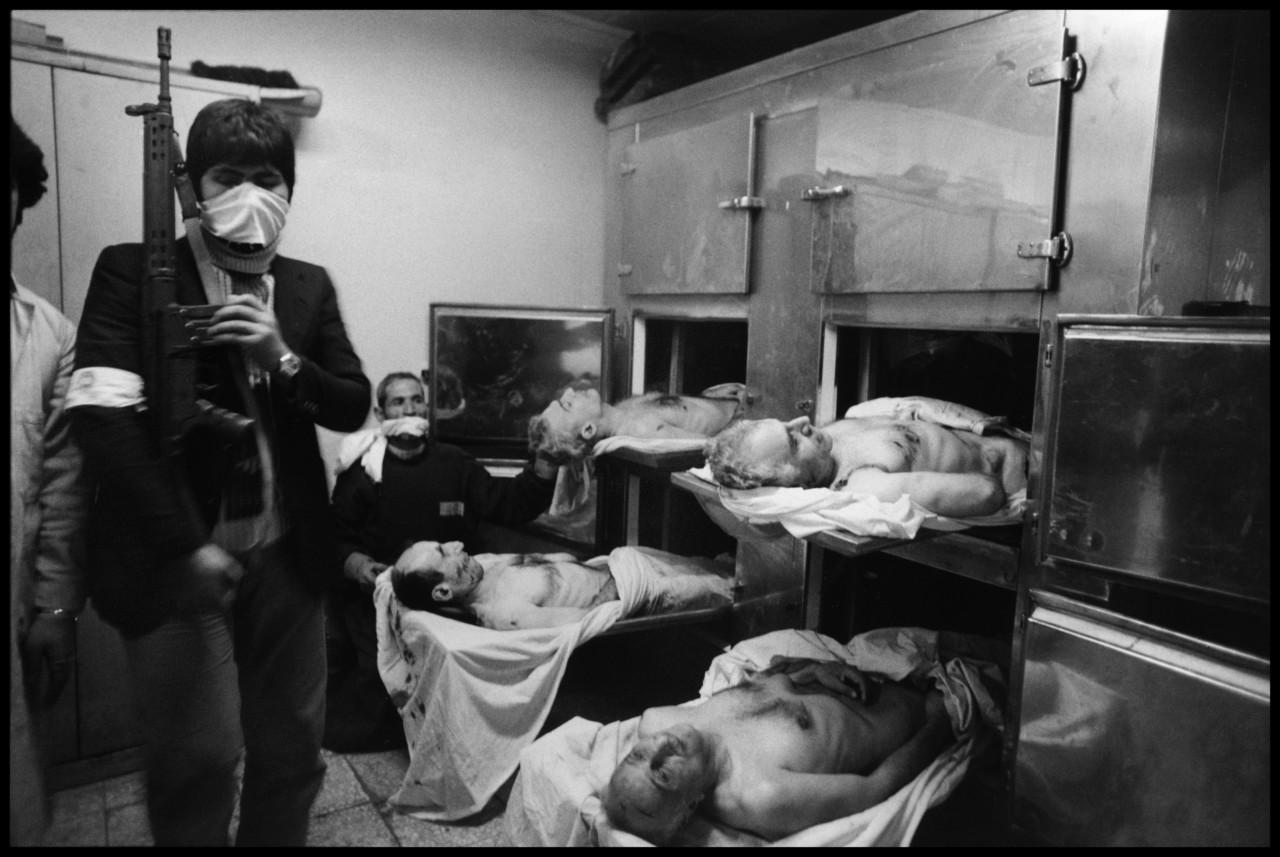

Khomeini’s arrival also marked a turning point for Abbas and countless others. “I decided that this revolution is not going to be mine anymore,” he said. A photograph he took that same month depicts a masked revolutionary, clutching an assault rifle. Behind him, the pallid torsos of four generals, executed after a secret trial at Khomeini’s headquarters, lie visible in the cold light of a sterile morgue. The bloodshed wrought by zealous revolutionaries, who were increasingly monopolizing the movement, was beginning to mirror the brutality of the Shah’s forces. Abbas continued to publish his pictures, making known the dark turn the revolution had taken.

On April 1, 1979, Iran voted by national referendum to become an Islamic republic and to implement a new theocratic-republican constitution. The country’s pro-western authoritarian monarchy had been replaced by an anti-western totalitarian theocracy, headed by Khomeini as Shiite cleric supreme leader. But, the violence continued and anti-western sentiment intensified, culminating in November of that year when American citizens were taken hostage at the US embassy.

The revolution itself was not only confined to Iran. “I could see that the wave of religious passion raised by Khomeini in Iran was not going to stop at its border; it was going to spread into the Muslim world. And it did and now it has spread across the world,” said Abbas, who left the country in 1980 and did not return for 17 years. His first publication, La Révolution Confisquée (The Confiscated Revolution), which was banned in Iran, charted what he had witnessed; the experience profoundly influenced his subsequent work, particularly his ongoing interest in what people do in the name of God.