American Geography

Matt Black’s six-year, 100,000-mile mission to create a project that will convey a nation’s grim realities, and help Americans to stop ‘unseeing themselves’

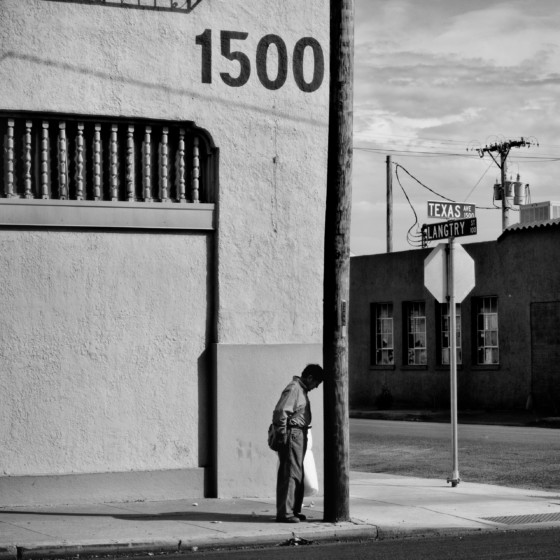

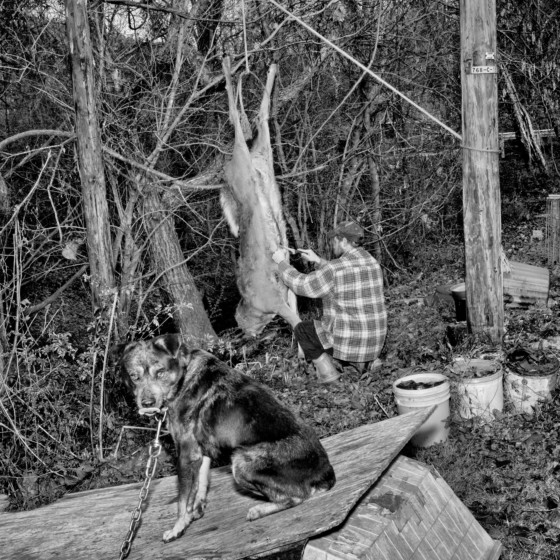

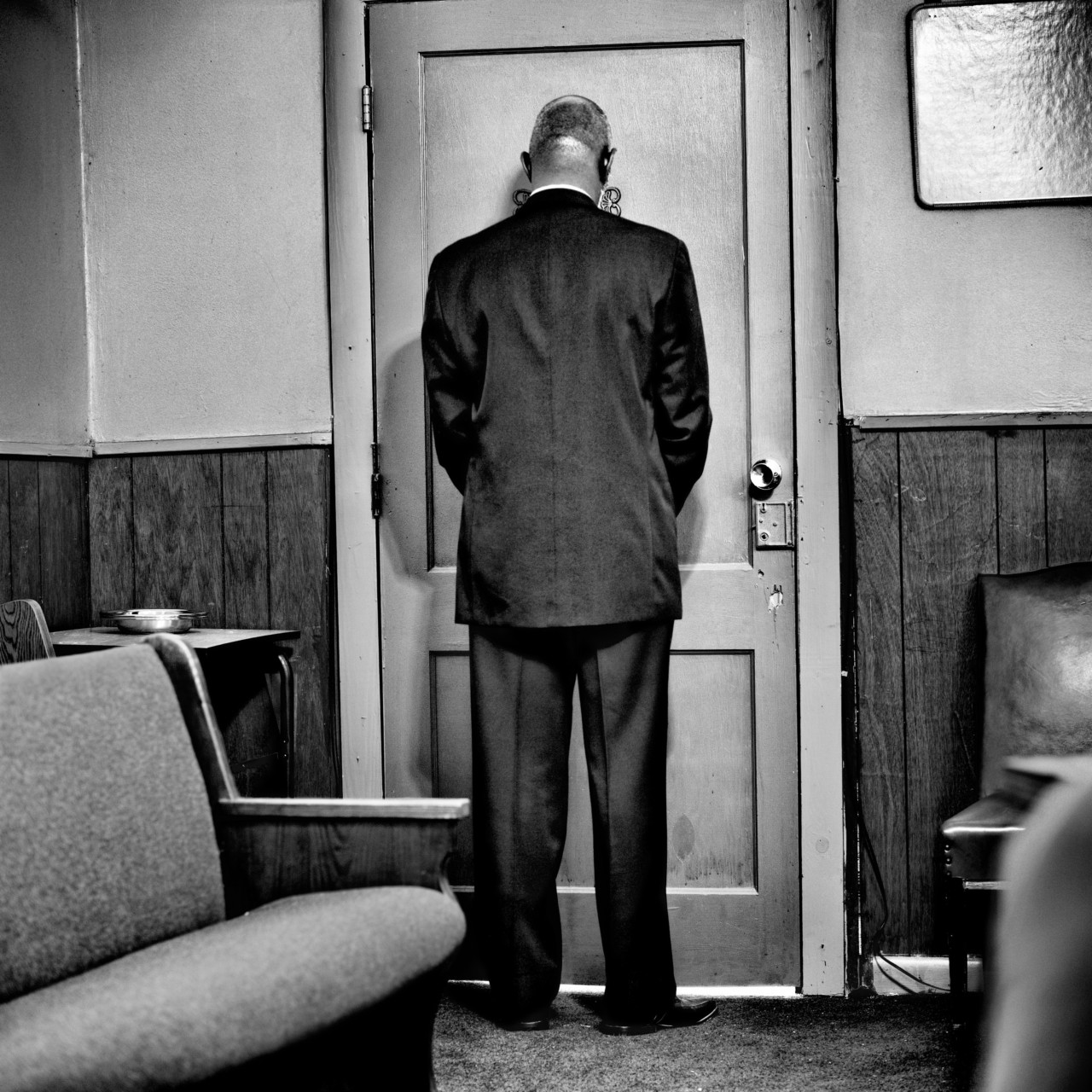

In 2013, Matt Black began photographing isolated communities in California’s Central Valley, the rural, agricultural area where he lives. In 2015, Black expanded the project to encompass the United States and completed his first cross-country trip, a three-and-a-half-month journey visiting dozens of communities across 28 states. Since then, he has completed four additional trips, traveling over 100,000 miles and making work across 46 states.

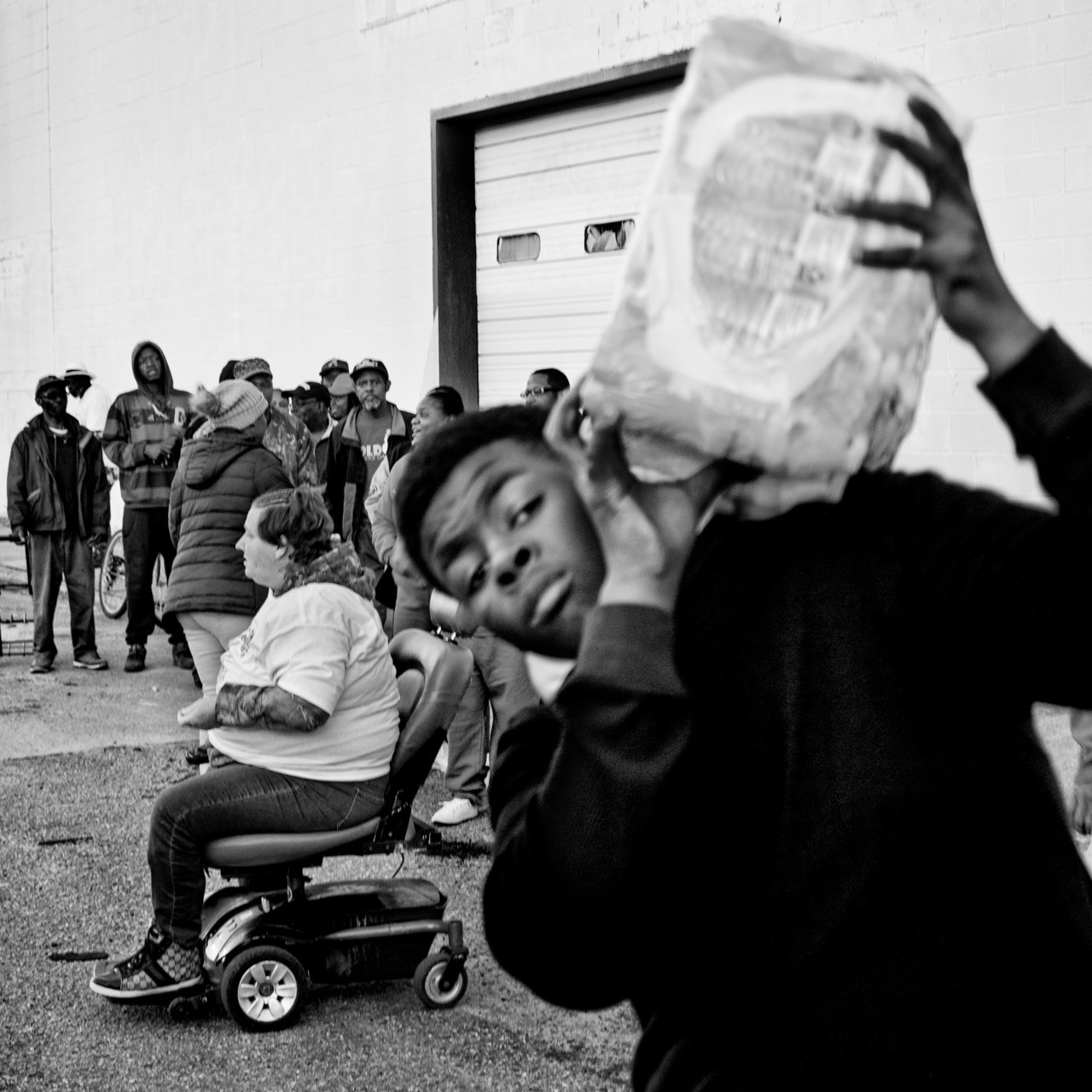

What had begun as a story of individual, isolated communities grew into a portrait of an increasingly divided and unequal America, created during a time of rising disparity and disunion. Until now, the project has never been published showing all aspects of the work.

Black combines his photographs, personal journal entries, and images of objects collected from his travels over the past seven years into one magazine: American Geography, designed by Yolanda Cuomo. The publication, produced in collaboration with Magnum Photos, is self-published by Black with the support of the International Center of Photography (ICP) and Marina and Andy Lewin.

By using two copies of the publication and hanging the spreads on the wall, American Geography can also function as an exhibition. Universities and schools in the U.S. that wish to incorporate Black’s work in their curriculum can use the zine as a vehicle for discussion of the issues that it examines through photography.

To mark the opening of Matt Black’s American Geography exhibition at the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg (see installation images at the end of this feature), Black and Fred Ritchin (Dean Emeritus of the International Center of Photography (ICP)) conducted a number of extensive conversations about his six-year, 100,000-mile journey across the United States, his home in California’s Central Valley, politics, social power, and perspective in America. Below we share an edited version of this conversation.

Fred Ritchin: When I knew this project, it was called The Geography of Poverty, and you changed the name. Could you explain why?

Matt Black: It was a feeling I had for a while. What I was doing was not a portrait of marginalized America, but a portrait of America itself. And the point that needed to be made was how much this is a part of American life, not something on its edges.

But do you think you’re dealing now with the mainstream of America, with this center of America? How would you define it?

What I’m getting at is at the center of the American experience. And people tend to focus on the bright and shiny parts of the country, but not the parts that are intimately connected to that prosperity but don’t share in it. For instance, where I live in the Central Valley, this area produces a quarter of the food in the United States, but enjoys very little of the benefit. It’s still one of the poorest areas of the country.

So I guess you’re also saying they’re not only overlooked, but actively erased, so that when media does coverages it is on the bright and shiny, or it’s on the extremes of violence or protests or whatever it would be. But the people who actually do the work, and provide the food for the country, are made invisible.

Exactly my point.

So you’re not seeing any social mobility then, the big American dream, Horatio Alger, and all that was that this is a country where it could pick you up by your bootstraps, and do what’s needed to get an education, skill sets, and move on up. You’re not seeing that?

I’m seeing the opposite of that. That your future is determined largely by where you are born.

And is there anything else in there? Is it also a gender issue, a race issue, ethnic issue, religious issue? Is it just the geography, or is something else part of that equation?

I mean, part of the way I’m feeling about this work, particularly in the context that we’re in right now, is that what needs to be made are universal statements. And that’s what I’ve attempted to do here in this work: to understand people united by this framework, living in areas that you don’t normally see put together in one body of work. Within that broad grouping there are many different issues, many different identities, and many different things going on. But what we’re seeing now is how these differences have been harnessed to divide. That’s completely contrary to where I’m coming from and where I think the country needs to be going.

"These hierarchies of power are what the work is exploring, who gets what and when and where, and who gets to say what America is. And that's what I'm talking about. America from the ground level is very different..."

- Matt Black

Here in New York, right now, there’s all these kinds of conversations which are based not so much on geography, but are based upon issues of race, sexual orientation, and religion as reasons why people are particularly brutalized, why people are discriminated against, why people bear burdens that other people don’t bear. And the reference is not to a particular place necessarily, the reference is to the inevitability of a diminished life potential, because one is for example, born black as opposed to white. But what you’re talking about seems to be something that’s very much like a social economic infrastructure, which involves everybody who’s born in that place. That even if you’re born Protestant or Catholic, or white or black or whatever you might be born, you’re still going to have enormous difficulties trying to extricate yourself from it or have any sense of self or self-worth?

Yes, that is precisely how I feel. And that’s something that’s just borne out by experience. None of this is to diminish those critiques, which of course are true and need to be made, but the broadening of those critiques, which I also think needs to happen. Place is important. It is another mechanism by which social power gets expressed in America.

So in your ideal vision then, the rest of us would be informed as to what’s going on in many geographies, in many parts of the country; we would take notice of it. Laws would be passed and so on, so that the benefits would be distributed more equally, so that there’d be more attention, more respect, for these other areas.

Yes, but first of all, we have to recognize what America is, and who gets to define what America is. These hierarchies of power are what the work is exploring, who gets what and when and where, and who gets to say what America is. And that’s what I’m talking about. America from the ground level is very different.

By the way, I think what you just said, that phrase you just used, “America from the ground level,” I think would be an excellent title for your project.

Well, that is what it is. If not in so many words, then through what the work reveals.

How do you compare this to, let’s say the 1930s, the FSA [Farm Security Administration], the attempts by the government to be supportive of groups of people who normally didn’t have a safety net? Are you seeing pretty much the opposite at this point? That the government is not being supportive and the people are being forgotten, as opposed to the 1930s, where we were actually using photography to look at people and to take them into account?

It is exactly the opposite, and on the part of the current government it seems to be motivated, not by caring, but by spite. If you pay attention to food stamps and other supports like that across the country, they’re being slashed to near-irrelevancy, to near-zero. And it’s being done with a sense of punishment and spite.

"I’ve attempted… to understand people united by this framework, living in areas that you don’t normally see put together in one body of work. Within that broad grouping, there are many different issues, many different identities, and many different things going on. But what we’re seeing now is how these differences have been harnessed to divide."

- Matt Black

So how do those poor respond to this? Do they think it’s with anger themselves, with bitterness, with a sense of being resigned, how do they respond?

In the work, I’ve tried to deal with the psychology of powerlessness, and how these things influence people’s thinking about themselves, and about their communities. And it is something I think is underestimated. In the end, these issues stem not just from finances.

They feel it’s their fault somehow?

Exactly. And that’s why talking about these things is so fraught, and so complicated in America because we still accept these ‘bootstrap’ ideas as being valid, when all experience is to the contrary. But people still accept these mythologies, “the land of opportunity” and so on.

So what initially motivated you to make this 100,000-mile journey?

I don’t know if you know that much about me or where I’m coming from, but just to step back for a second, my goal for many years as a photographer was to focus on the place where I live, to use my work to be a voice for this place. And when I first started this project, the focus again was on this part of California and trying to take a step back and take a different look at it. I did that for about a year.

But then what happened – with the work and also with myself – is I felt like I had 20 years of working in California, but when I would work on ideas here, I always had in mind the universal. To me, the connections were obvious, it was clear that we’re all connected, but I found that few people were willing to make that leap with me. It almost becomes a self-defeating thing. Because to say, okay, for example, “in the Central Valley of California or in rural Mississippi, these stories exist” — by doing it that way, it makes it easier to ignore. That approach allows people to say, “Keep it over there, somewhere far away from us.” So, the idea was to try to bring it as close as possible, to show how universal these issues and these sorts of experiences are in this country.

Also I’m trying to grab at something else that I think is really important. Coming back to the Central Valley, it’s essentially a colony, an interior colony of America. It’s an extractive thing. It’s not included in this American story that’s been written elsewhere. It just feeds the raw materials for that American story to unfold. For me growing up, there was a sense that the place I’m from is not part of what I see on TV. And there’s a built-in sense of disempowerment that goes with that. Anyone who’s from a place like this knows the feeling very well. I tried to harness and internalize that feeling as much as possible, the tragedy and disillusionment that goes along with that. I used that to inform the pictures.

"To say, for example, 'in the Central Valley of California or in rural Mississippi, these stories exist' — by doing it that way, it makes it easier to ignore… So, the idea was to try to bring it as close as possible, to show how universal these issues and these sorts of experiences are in this country."

- Matt Black

How big is that America that you’re talking about? What percentage of the country in your mind do you see it as?

This is the country. It is. If you go and look on the ground level, this is America.

And these people and these areas have been not only disenfranchised through TV, movies, newspapers and magazines… They’ve been failed through negligent government policies, lack of support networks, denied the chance of higher education, skill training, and other services?

And clean water, clean air, health care, life expectancy — just go straight down the list, any which possible way that injustice can be manifested, it’s there.

So it seems to me then on this trip, you went from the geography of poverty, like you said before, to a sense that this is the country. It’s not just a segment of it, but this is the way the country operates.

Yes. And if this can help broaden people’s understanding of what America is, and if it can help build connections between these different places and more of a sense of universality in these experiences, then good.

Do you feel that the impact of Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” could be replicated today in any way? Do you think that image, your images, anybody else’s images could focus the country, or do you think we’re in a different place now?

Yes, I think they can, they have, and that they continue to. The hard part about trying to identify those pictures is we don’t have the benefit of retrospect. I don’t think we’re going to know what those images are until later. But I still believe that photography has the ability to crystallize thought and emotion, and to motivate people to think and connect with each other. If I didn’t believe that, I couldn’t be doing this.

But do you think it works better on a local level, nationally, or internationally? I’m not seeing that many iconic images. We are going through a massive depression, a pandemic, but I don’t see the equivalent of the Lange images, an icon to focus upon. Yes, I agree with you that there many images have impact, but I’m trying to get at is it a series of images that make a difference now? How does it work differently? Does Facebook do it better than The New York Times used to do it? What’s your opinion?

Yeah, I mean, photography has changed. It’s much more common. And I think you’re right, now it’s more about a sustained engagement than the individual image. And maybe that’s good, maybe an individual image can simplify things too much, but I still think despite that, despite the fact that we’re just kind of awash in images, photography still can and does perform that function. It communicates on a human level and an emotional level. I don’t think that ability has changed at all.

But do you think it’s possible somebody in New York will look at one of your images and say, “Well, the Horatio Alger lives. We have upward mobility. It’s that person’s fault. They didn’t get the education. They didn’t do what they could have done.” Whereas if you show it in the Central Valley, somebody would say, “Well, there is no education they could get. There is no chance they could have got.” So that the context or seeing the image would be different or do you think that we transcend all that?

I think cynicism is not limited to any particular group. We can have cynical reactions from across the spectrum.

"[These places] feed the raw materials for that American story to unfold [elsewhere]… And there’s a built-in sense of disempowerment that goes with that. Anyone who’s from a place like this knows the feeling very well. I tried to harness and internalize that feeling as much as possible, the tragedy and disillusionment that goes along with that. I used that to inform the pictures."

- Matt Black

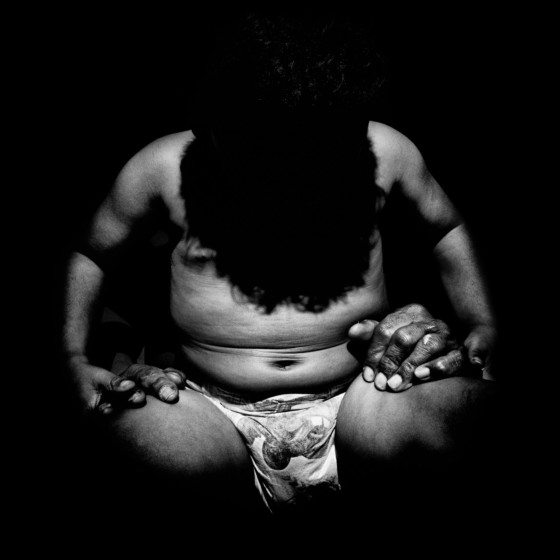

Okay, now let’s switch to something else, which is your printing. You have a very distinctive quality of print that you make. You’re also working in black-and-white. And what are you trying to get at with the print? They’re very dramatic images the way you make them and so on. What’s your intention in the printing and the choice of black and white?

The pictures look to me how pictures should look. And I can go into a little bit of detail about what it’s like to photograph in an environment like that of the Central Valley – it’s very difficult to get a full-range image in a place that is so saturated with sun. When I learned photography, it was all in black and white, and to get a full range image, you had to push your film in order to get a black and a white. You had to use contrasty film, or everything just came out grey. And since then, I’ve never really changed or questioned it. To me, that’s just how photographs look.

It’s funny, David Goldblatt said pretty much the same thing as you. Living in South Africa, they asked him, why don’t you have light like the Europeans? And he said, the light here is completely different, that it’s never going to look like them. So that’s what you grow up in, that’s what you see.

Interesting. Yes, that’s it. And to press that idea further, there’s a lot tied up with what you grow up in, that’s what you see. It’s a part of you, it’s how you see things. It’s what makes your work distinctive, and you can hone it but not make it up from scratch, and every photographer has to find it for themselves and then explore it as fully as possible because that’s what they have.

Just to get a little deeper in this, you grew up in the Central Valley, you’re still in the Central Valley. Is the choice because of culture, because you really like it there? Is the choice because of family, friends, because you’re familiar with it? What went into that choice? A lot of people move away from where they grew up, especially from areas that have their share of hardships as the Central Valley does.

Well, first of all, it’s home and yes, family is here. And then secondly, there is a degree of commitment, of feeling like I have an obligation to continue to work here. And then third, it gives me the proper perspective. It would be hard to maintain my own clarity without being here. So it’s all three of those things together, equally weighted.

I started working at my hometown newspaper out of high school, and my understanding of the role that photography can play and that stories can play in places like this, has been there right from the start for me. It’s about who gets to choose what gets photographed and who gets to define what’s important and the power that comes with that. That was embedded in photography for me from the start.

So as an insider there’s an authenticity for you in remaining in the Central Valley, being the inside guy. That allows you to see things differently than an outsider would, I’m assuming.

Well, I think the insider versus outsider thing is really complicated. I think the moment you pick up a camera, you are automatically outside the situation you’re in. So I don’t presume to adopt any sort of personal morality out of what I’m talking about. What I mean is for me personally, to maintain my clarity of thought, it just serves me better to be here.

"I still believe that photography has the ability to crystallize thought and emotion, and to motivate people to think and connect with each other.” … “It communicates on a human level and an emotional level. I don’t think that ability has changed at all."

-

How do you know when you’re doing the right thing? This is part of what I was asking about your working method, do you talk with the people? You wouldn’t make an image of somebody you just passed on the street standing in front of something. You’ll talk to people.

Absolutely. A big part of this project has been interviewing people and getting their voices and stories. I would never make an image that I felt was going to harm somebody.

Okay, and how would you define doing harm to people with photos? What does that mean?

To me, it’s important that you’re taking an image that is truthful and not denigrating. An earned image that’s fair. This project has been made up of two very different ways of working, sandwiched into one body of work. One is walking the spaces, walking the streets, cities, and towns, just observing and making images like that. The other has been the series of very focused stories where I’m working much more as a traditional photojournalist, which my own personal history and background is more aligned with. For example, I just finished a big project about drinking water across the US, incorporating a half-dozen or so different areas of the country connected by contamination and lack of access to clean drinking water. Other stories included going to Puerto Rico after the hurricane, the run-up to Standing Rock, Flint. With those focused stories, it’s about spending time with people, working in a much slower fashion, it’s very much a collaborative journalistic enterprise.

Explain collaborative, collaborate with the subject, with the writer?

Collaborative in terms of communicating a story. For instance, when you’re photographing contaminated drinking water, you’re going into people’s houses and you’re seeing bathrooms and how people interact with water in all these different ways. Mothers trying to give their children baths by pouring in little tiny bottles of drinking water. So it’s collaborative in terms of agreeing this is something that should be documented. And respecting the ability of the camera to change things.

So you’re not taking advantage of the people, you’re working with the people to show.

Absolutely, how else could you enter these intimate spaces? It’s a collaborative process in order to achieve those images.

"There’s a lot tied up with what you grow up in, that’s what you see. It’s a part of you, it’s how you see things. It’s what makes your work distinctive, and you can hone it but not make it up from scratch."

- Matt Black

In American Geography, this big project, do you ever allow a stream of images? Let’s say you’re talking about drinking water and you have many images to show that this problem exists all over the place, not just in Flint. To convey that would you allow a stream of images, or is it always the single image that you’re working off of?

I believe very strongly in the power of an image. Like what we were talking about earlier, how to establish that kind of emotional response that photography can do. Of course, the more single images you have that can do that, the better. So it’s not fetishizing the single image; I want my images to evoke this response, this emotional response. I need to feel convinced that my pictures do that.

No, my question is only that if I’m the viewer I see an image of this, let’s say taking a bath with these bottles of water being poured in. And I say, “That’s terrible. Where is that?” And it says it’s in Flint or wherever it is. And I then say, “I didn’t know anything about that.” Then if it was on the screen, I could click and see 20 more images of other places, same subject. Or if it was in a book, I’d turn the page and suddenly instead of a single image, there’s a double page with 12 small images. I’m asking if you ever think of things like that or you remain committed to the single image.

I remain committed to a strong emotional reaction in response to the photographs. To me, photography works best when the images provoke a visceral response. And the fact is those images are pretty rare.

Let’s talk about text a little bit, because it’s outside the frame and a way of contextualizing the imagery. You have a lot of these kind of diary segments describing meeting people, what it was like, what you felt. Is your intention to contextualize your photographs this way? For example, here’s somebody I met without access to drinkable water. And the text then says X percent of Americans don’t have drinkable water. Do you think of it that way, or is it a more lyrical approach without those kinds of overarching statistics and so on?

My feeling about both the photographs and the text is that I am taking you with me, and I’m anticipating us both to be approaching things in an emotionally open way. And then we will experience those realities and become better through it, become more aware, become more sensitive to other people’s experiences. I have a hard time using facts as kind of a bludgeon. We’re surrounded by facts; what we’re not surrounded by is meaning. That’s what I feel photography does best.

The emotional side, the empathetic side, the experiential side.

Absolutely. To me, the important thing is to make sure that I’m constantly feeling that my intention is pure and that I’m staying true to that. Then all these other things can come through. And what I mean by these other things is sometimes very specific things, in terms of documentary, but also very abstract things and things that are hard to pin down, feelings and emotions. But if all of those elements are encompassed in a true way, it comes across. It comes through. And that’s where I think photography works best.

Do you get more response to the work outside the US, from Europe or elsewhere? Or do those in other countries see your work as a more exotic?

I talk to people from elsewhere, and they say this is the first thing they see when they come to America. They’re shocked by the visual, street-level reality of America. And I think that just points out… again, this myopia that we were talking about before, Fred, this blind spot that Americans have. It becomes so easy to unsee ourselves.

Signed copies of “American Geography” are available on the Magnum Shop. Three images from the project are also available as a part of the curated Magnum Editions Posters.

The companion volume to the original book, titled “American Artifacts,” is also available to pre-order.