Borderlands

Curator Jen Sudul Edwards reflects on the archive of Magnum photographers' work made on the border between Mexico and the US, and upon the role of photography in charting political change and witnessing to movement of people

Magnum photographers have for decades photographed the border between Mexico and the United States. These images have charted its transition from a fluid, liminal area of movement, social and cultural exchange, to a castellated, militarised zone. Here, Jen Sudul Edwards, Ph.D. – the Chief Curator and Curator on Contemporary Art at The Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina – reflects on the history of one of the most politicised of American spaces, and Magnum’s visual archive on the borderlands.

Sudul Edwards’ photography exhibition, W|ALL: Defend, Divide, and the Divine, about the historic use and artistic treatment of walls throughout time and the world, is now on show at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles. More information, here.

“The camera is an instrument that helps people see without a camera.”

Dorothea Lange, Milton Meltzer, Dorothy Lange: A Photographer’s Life. (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1978), vii.

“In the field of world policy I would dedicate this nation to the policy of the good neighbor – the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Inaugural address, March 4, 1933.

[The detective said] “I’d have expected over here there’d have been—you know what I mean—life. You read things about Mexico.”

“Oh, life,” Mr. Calloway said. “That begins on the other side.”

Graham Greene, 1938, “Across the Bridge,” Twenty-One Stories. (New York: Open Road Integrated Media, Inc., 2018), 53.

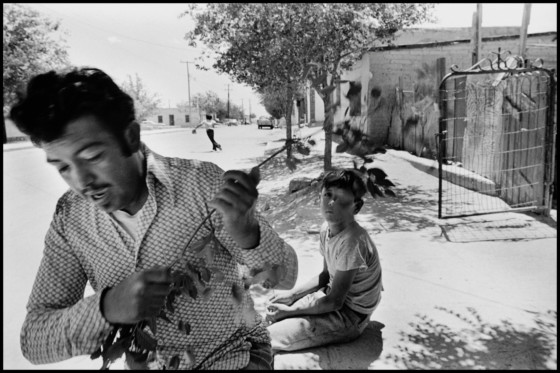

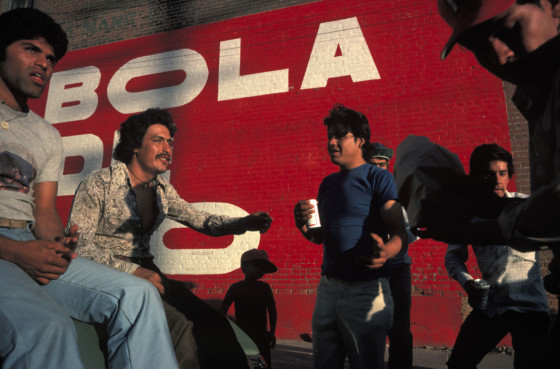

In 1975, inspired by Graham Greene’s accounts of his own travels through Mexico, Alex Webb flew to El Paso, Texas, walking across the bridge into Juarez, Mexico, to explore the shared space of the border. “That decision,” Webb wrote, “changed the direction of my photography—as well as my life.”[1]

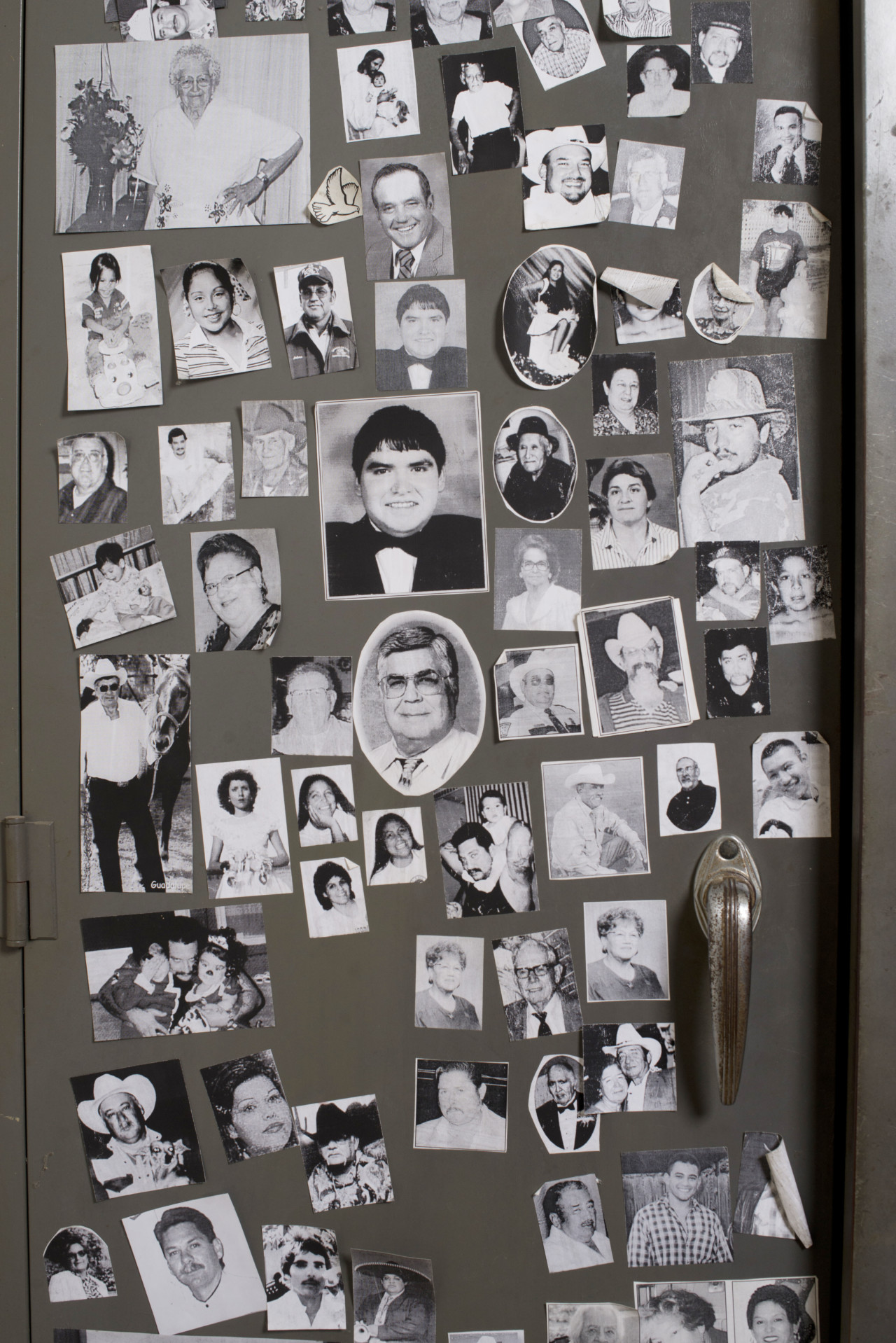

Forty-five years ago the border between the countries was palpable, if mostly invisible. Life in the United States and Mexico differed, but between the two people and cultures flowed relatively freely. “There was a sense of ease in the relationship between the two countries,” wrote Webb.[2] Children in Tijuana crossed into San Diego every morning for school. Farm workers and housekeepers left Mexican homes to work on United States properties. Webb tells the story of even basic services being found on the U.S. side: “In the late 1970’s, for example, the residents of Santa Helena, Mexico—because the mail services in Mexico were so poor or perhaps because they had relatives in the United States— would have their mail delivered to Lajitas, Texas, and walk across the Rio Grande each day to the U. S. post office to pick it up.”[3]

The border towns shared a culture as they shared a people, a commonality Webb’s photographs captured. (He published a survey of this work in his 2003 book, Crossings.) “In many ways,” Webb recalled, “the border felt almost like another country, neither the U.S. nor Mexico, but a land between, with its own traditions and a neighborly spirit of cooperation.”[4]

In 1977, a few years after Webb crossed the bridge into Mexico, Susan Meiselas traveled through the country on her way to Central and South America. Shortly thereafter, she photographed her El Salvador and Nicaragua series, groundbreaking photographs that captured and transmitted the impassioned faces and determined rebellion of people focused on taking control of their land and their government.

Meiselas kept revisiting the theme of Latin America—the place and the people, both in situ and as migrants. In 1989, she returned to the U.S.-Mexico border on assignment from Arthur Ollman, curator of the Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego, to participate in a project that documented the border with six photographers, three Mexican and three from the United States. Meiselas started the project with the knowledge of those years in Central and South America, when she lived with violence and uncertainty. That experience colored her perspective of the migrants crossing from Mexico with a specific knowledge: ““It was no surprise that people are leaving the turmoil of this region to seek some kind of ongoing, stable life.”[5]

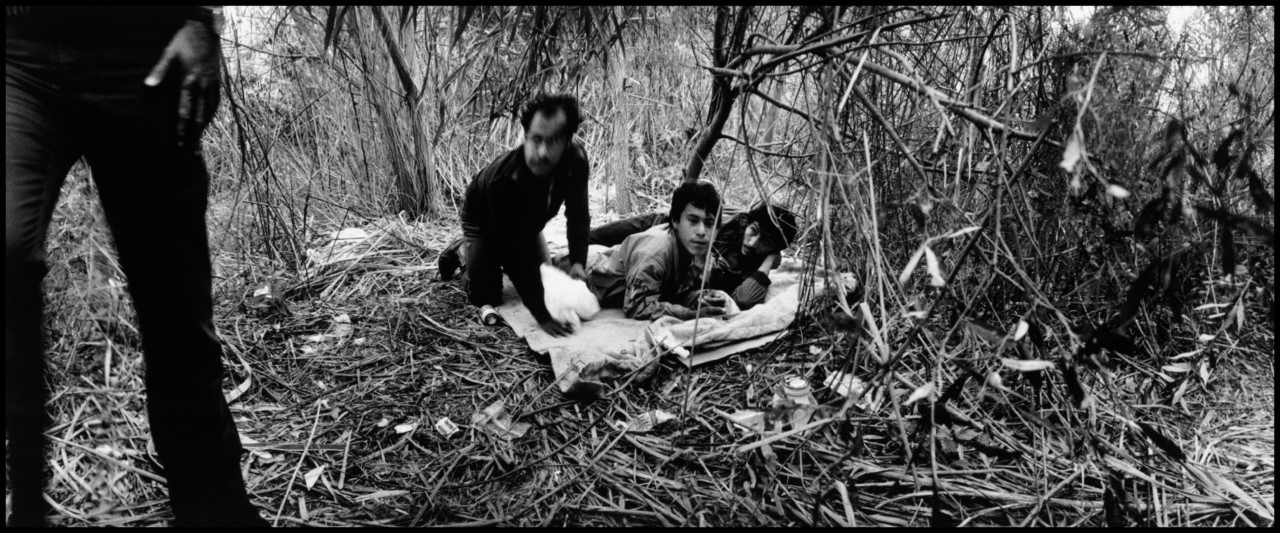

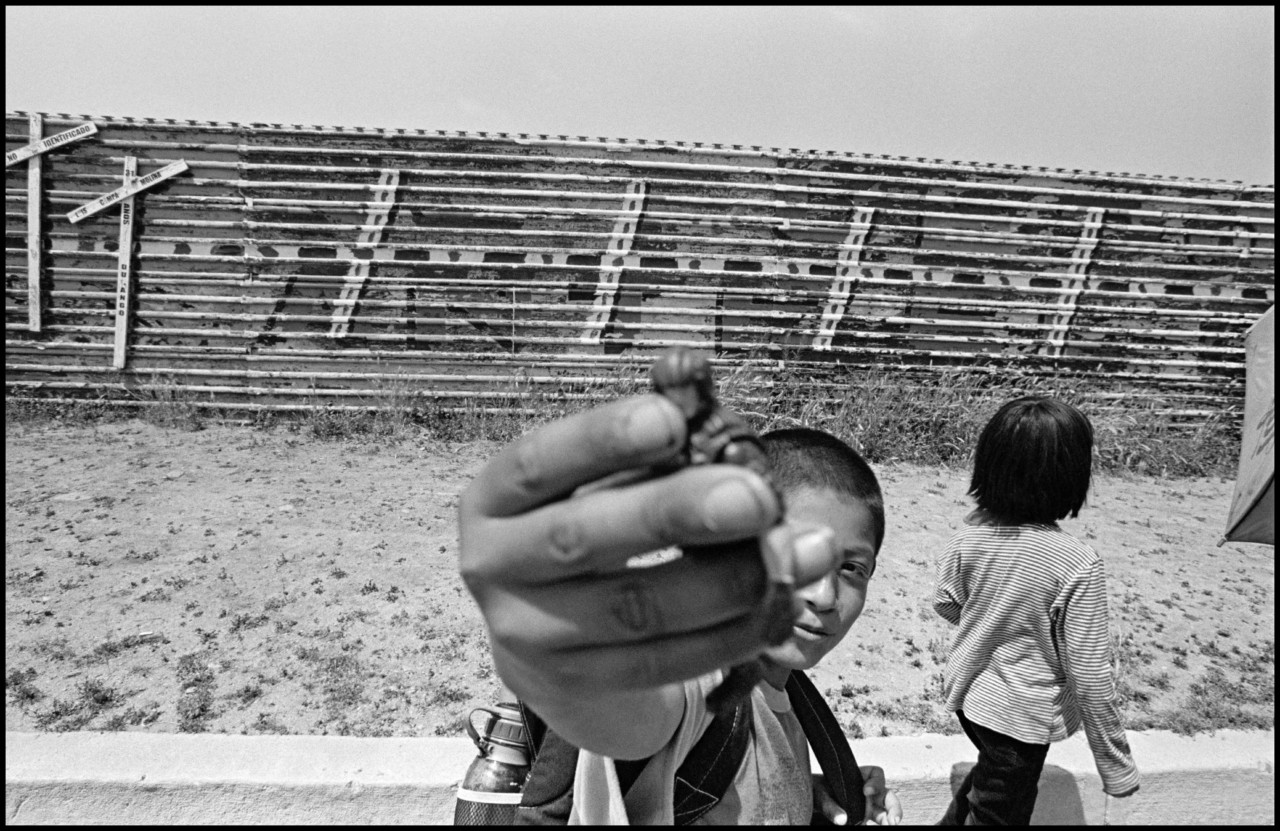

Ollman’s project led to Meiselas’s exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago exhibition entitled Crossings. She worked with both migrants and la migra (the immigration authorities) to photograph the cat-and-mouse game between the two. These images differ—in feel and composition—from the Latin American images Meiselas shot previously. When I spoke with her about the U.S.-Mexico series, I noted that the faces in Crossings appeared much more resolute, resigned, locked in the present, than in her previous series. El Salvador, Nicaragua, even Carnival Strippers and Prince Street Girls featured faces visibly struggling, either in full blown fury or in a quiet look, as if these people were striving for the next something, even if just in their minds.

In contrast, the migrants seemed fully invested in the present, dealing only with the immediate. Meiselas pointed out the difference in their circumstances: “There was a lot of fight [in the other series]; the fight for Central America—they thought they could transform their society and make it more equitable. When people are coming across the border, they are giving up on their homeland. That’s a very hard thing to do. There’s an uncertainty; maybe it’s that uncertainty that you are seeing. . . Because at the moment of their capture, they are faced with the question of do they begin this whole cycle again. Do they have the resources? Have the coyote [people paid to help migrants cross illegally] just dumped them there?”[6] In these situations, a migrant’s condition is moment-to-moment as opposed to a long arc of action.

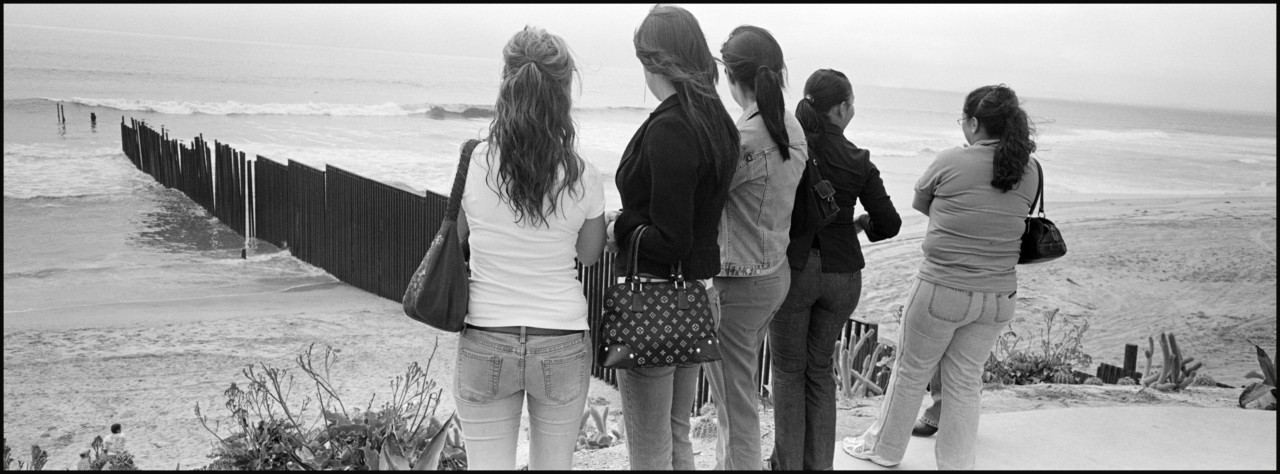

Meiselas also changed her mechanics. For the U.S.-Mexico border series, she used a widelux instead of the Leica 35 mm employed previously. “I didn’t start with a widelux,” Meiselas recalled, “but ended up feeling like that camera best captured the theatricality of what I was seeing. It got the feeling of seeing people running and moving. It’s all about moving: migra moving in and off sites along the interstate, people hiding, all kinds of surprise encounters. That particular format of the camera captures the dynamic I was trying to portray.”[7] The broader panorama shifted attention from a central action to a pervasive environment, one that, despite the movement that preceded the image, felt static and unchanging instead of frenetic and fluid, as in the pictures of revolution.

Webb and Meiselas began documenting a border on the cusp of a dramatic change. Migrants from the South had been seeking refuge in the North consistently over the last century and the relationship between the two countries was symbiotic. Whether workers came to the United States for safety or economic reasons, they also provided an agricultural and domestic work force necessary for the comfortable status quo of the United States economy. “We all like to eat,” Jerry Ferguson, a Utah farm labor spokesman, said in a 1991 interview, “They’re the only ones we can find to do the manual work to produce the food. You can’t get white people to do it.”[8]

Throughout the 20thcentury, the United States government recognized this, structuring immigration policies that allowed for migrant workers to enter the country as laborers.[9] Because passage was easier and the penalty for getting caught was release in Mexico, attempts would be repeated—and migrants made roundtrips. Workers came to the United States daily or seasonally, sent money home, and then returned to their families in the South when the work was done. Meiselas heard this story repeatedly from migrants: “I would say many of the Latins that I know in this country are here with the notion that they are going home. If it’s easy, they do; and if they can’t… they’re not leading the lives they want to here.”[10]

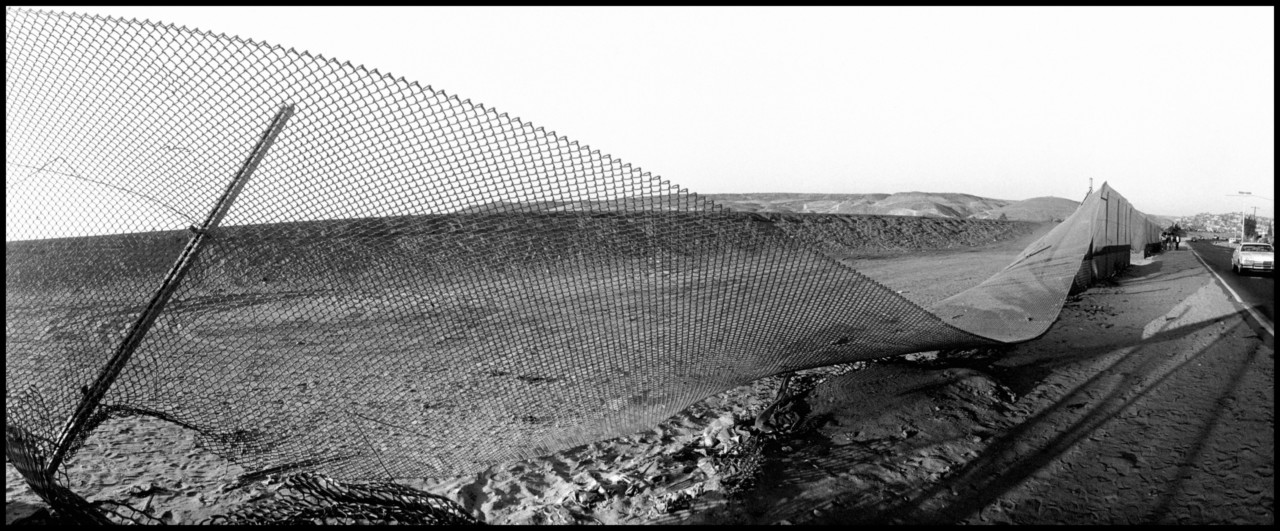

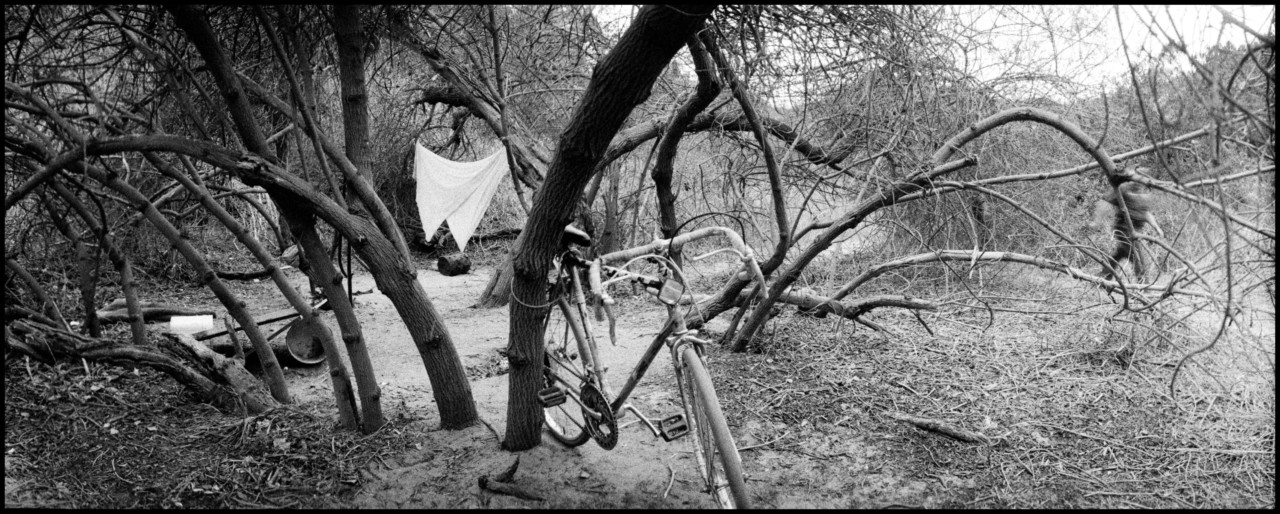

Migrant workers continued to be necessary, but at various points, both sides erected walls for reasons of security, whether physical or emotional. In the 1970s and ‘80s, chain link fences went up, like the one in Meiselas’s Tijuana photograph [see top of page]. El Paso residents nicknamed these “tortilla curtains,” because they were so flimsy.[11] Border patrol on both sides worked to prevent successful crossings, but they happened frequently.

"The increased militarization of the region, manifested in corrugated metal fences and surveillance technology... would exponentially intensify a migrant’s struggle"

- Jen Sudul Edwards

Following Mexico’s 1982 debt crisis, it became essential for many to attempt entry into the United States—legally or not—in search of work. As many as 10,000 people a day attempted to dash across the border, with only a fraction of them being caught.[12] Concerns about drug smuggling and crime rose in proportion. On September 18, 1993, the border patrol chief in El Paso, Texas, Silvestre Reyes, initiated a program called Operation Blockadein which he created a human wall of 400 border patrol agents that extended 20 miles between Juarez, Mexico and El Paso. This shifted border policy, in his words, “from a strategy of apprehension to one of deterrence.”[13] Illegal dashes ceased, petty crime declined 15%, and border patrol stopped harassing Mexican-Americans on the streets to verify their status because El Paso officials perceived the border as secure.[14]

Other border cities throughout the southwest adopted Reyes’ strategy of deterrence, which was renamed Operation Hold the Line. On February 2, 1995, President Bill Clinton formalized it as a federal policy with his National Border Patrol strategy to further police the border from California through Texas. This led to the increased militarization of the region, manifested in corrugated metal fences and surveillance technology. These strategies, in turn, would exponentially intensify a migrant’s struggle: crossing through the land.

"The overwhelming presence of the landscape in this human story pervaded many of the photographers’ images of the U.S.-Mexico border"

- Jen Sudul Edwards

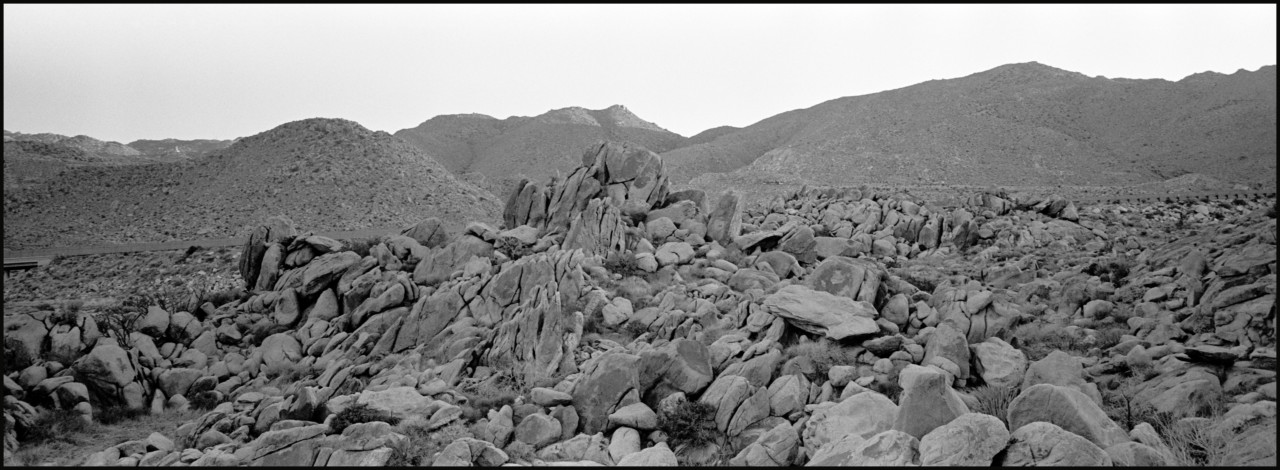

In 1994, the Border Patrol published its plan, “Prevention through Deterrence,” which recognized that militarizing the border selectively would push people to cross in dangerous, extreme environments. One possibility was that the exhausting trek would slow the migrants down and make them easier to catch, or deter them from coming at all. The other was that many would die making the journey: subsequent statistics revealed this outcome. In the 1990s, Tucson, Arizona, tallied about 18 deaths a year of those trying to cross the border through the desert; after the border was sealed in the 2000s, the count rose to over 200 deaths a year.[15] And those numbers recorded just the identified dead; many people listed as missing were never recovered, and so did not figure in the rising statistics.[16] The federal government anticipated this possibility; a 1997 report presented to Congress by the United States General Accounting Office acknowledged that “deaths may increase (as enforcement in urban areas forces aliens to attempt mountain or desert crossings).”[17]

"To see these monuments in photographs... revealed their disruptive nature and the desperate assertion of control over a land and a people"

- Jen Sudul Edwards

As in Meiselas’s photographs, the overwhelming presence of the landscape in this human story pervaded many of the photographers’ images of the U.S.-Mexico border. While the geography’s narrative was one constructed by governments—the failing regimes to the South and the frustrated responses by the United States—the subjects included the people and the land.

Walls, fences, and border markers snaked through a landscape that seemed resolutely undisturbed by people. The photographs—like those by Jerome Sessini, Carolyn Drake, and Larry Towell—highlighted the absurdity of trying to contain the vastness.

Manmade barriers cut through the backyards of residents—both animal and human—and disrupted migration for all.

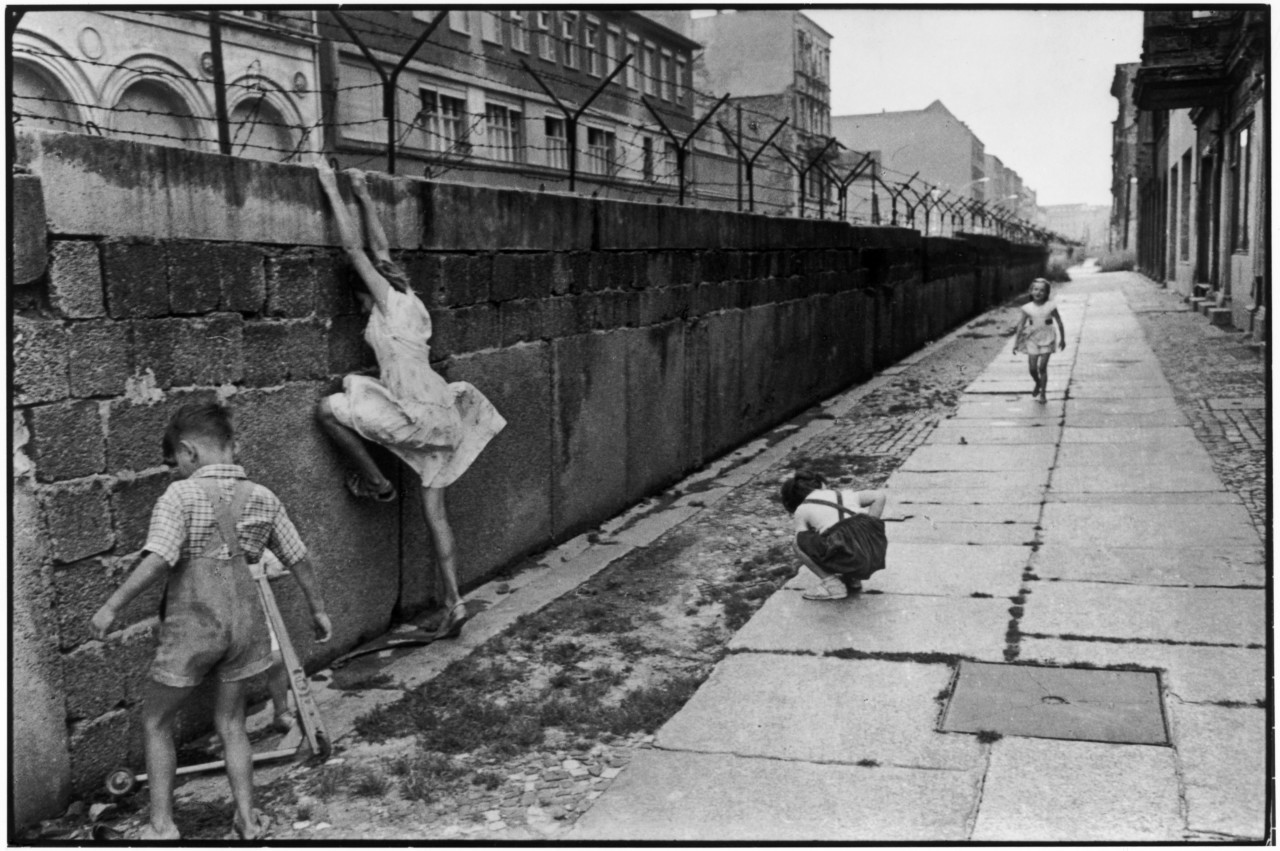

The photographs of the U.S.-Mexico wall differed dramatically from walls documented in the past. The Berlin Wall, Jewish ghetto walls erected in Poland during World War II, the “separation barrier” containing Palestine within Israel—these were urban constructs. They fit in a landscape of property markers, privacy fences, and security gates.

But in the last twenty years, as nations erected border fences in record numbers—70 were built since the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall and the majority went up in the 21stcentury—more images depicted concertina wire, corrugated metal, and concrete slabs slicing deserts, forests, grasslands—solitary stands taken by absent powers, in the tradition of Hadrian’s Wall erected millennia ago. To see these monuments in photographs—frozen in history, seemingly objectively catalogued in situ—revealed their disruptive nature and the desperate assertion of control over a land and a people.

Cristina de Middel’s series of Mexican athletes at the Tijuana border wall responded to this absurdity that morphs into tragedy. Begun in 2014 during the Obama administration, these photographs constituted a chapter in a larger, conceptual project about the U.S.-Mexico relationship that riffed on Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth. De Middel explained:

“Most of my projects come out of my frustration of reading in mass media how certain contemporary issues are approached and addressed. I’ve been living for 5 years between Mexico and Brazil and I was very disturbed by how the migrants were perceived by what’s mainly US newspapers have been telling people. I tried to shift that perception. It started in 2014—I was in the US and I decided to just drive along the border. I found this place called Felicity which is the ‘official center of the world.’ Immediately, the book by Jules Verne Journey to the Center of the Earth, came to my mind.

I found the athletes on line though athletic clubs in Tijuana. The captain of the athletic team loved the idea and we worked for three or four days by the fence. There were even athletes who had never been close to the fence. We think that it’s all Mexicans who cross the border, but it’s really Southern Mexicans who cross the border, not the Mexicans who have any trouble crossing. It’s really a socio-economic, class issue. It’s really the people from Oaxaca and Chiapas. People from the North don’t really need to make that journey. They don’t have any aspirations to go to the US. Those wealthy families just don’t get close to the fence.

But the skills you need to finish that journey, to cross that wall, they are the same. The physical part of it is the same; they just don’t have the emotional or financial need to do it. But they are very well-prepared to do it. So taking the elite of people who can do it, but don’t need to do it. They don’t need to cross, but they are speaking for others.”[18]

Once Donald Trump took office, de Middel realized that photographers could not afford such levity in their images; the situation had become too dire. Since the athletes series in 2014, de Middel returned to the border to work with refugees, beginning a more sober chapter of her Journey to the Center of the Earth project. These photographs continued to convey resilience, depicting people determined to live life despite the barriers before them. Juxtaposed with James Sessini’s heartbreaking image of a Sunday mass held before the dense grates of a border wall section, that determined resilience is elevated to perseverance.

How many ways to consider the walls we erect? They isolate; they protect. They delineate; they disrupt. They articulate another space, formalizing that feeling Alex Webb had of the border land as “another country, neither the U.S. nor Mexico, but a land between.” Despite the new barriers and new rhetoric, that feeling continues, as Susan Meiselas captured poignantly in her 2018 image.

In the United States, at least, for the last century, many romanticized the border wall; people often toss around the final quote from Robert Frost’s poem Mending Wall–“Good fences make good neighbors”—to justify the poetic musing.

But as with so many artistic expressions that become cultural aphorisms, the ambiguity of that poem has been lost in a soundbite. While the narrator’s neighbor asserts the need for defined borders, the narrator passively consents, but considers the absurdity of humans imposing physical borders on the natural landscape. The poem begins, “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,/That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,/And spills the upper boulders in the sun; And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.” Humans and nature alike undermine the determination and confidence with which the architect builds the barrier—one removing, the other repairing, though Frost leaves it to the reader to decide who does which task.

The sculptor Cannupa Hanska Lugar has remarked that, in Native American culture, we belong to the land, the land does not belong to us. Once we forget the former and assert the latter, the land becomes property—something to own, to mark, to possess. Yet that posession is always temporary, tenuous. No matter how thick the concrete, it can crumble. No matter how dense the concertina wire, it can be cut. No matter how high the mesa, it can erode. Like tides, walls rise and fall with time and the gravitational pull of political powers. And like those waters, they leave their mark, but can be elided and subsumed with the new bodies that subsequently assume the space. Fortunately, we have photographers who record that change and both their momentary and lasting effect. In the words of the critic Fred Ritchin, they “bare the questions that have been hidden by the answers.”[19]

Jen Sudul Edwards, Ph.D., is the Chief Curator and Curator on Contemporary Art at The Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina. Her photography exhibition, W|ALL: Defend, Divide, and the Divine, about the historic use and artistic treatment of walls throughout time and the world, is on view at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles from September 21, 2019 through January 5, 2020.

Notes

[1]Email with author, April 19, 2019.

[2]Ibid.

[3]Ibid.

[4]Ibid.

[5]Conversation with the author, April 2, 2019.

[6]Ibid.

[7]Ibid.

[8]Tony Semerad, “Migrant Farm Workers: Utah’s Invisible – but indispensable – population,” The Salt Lake Tribune, 3 Nov 1991, A1.

[9]The first formal program for allowing Southern migration was the Bracero Program, active from 1942-1964, which allowed foreign workers, predominantly Mexicans, to come in under contract with agricultural entities. It brought in approximately 4.5 million workers. Ultimately, many employers abused the program—not paying workers, offering deplorable housing—which led to the government disbanding it. Over the years, a series of programs replaced it, allowing noncitizens to cross the border to work in the country, principally in farming. In recent years, employers applied for HB visas for one to three years. With the recent tightening of immigration policies, the United States presently issues only 200,000 HB visas a year, not nearly enough for farms to have a legal workforce to manage the land. (Statistics from Cokie Roberts, “Ask Cokie,” Morning Edition, June 14, 2019.)

[10]Conversation with author, April 2, 2019.

[11]RadioLab, “Border Trilogy Part 1,” March 23, 2018. Transcript: https://www.wnycstudios.org/story/border-trilogy-part-1

[12]Ibid.

[13]Silvestre Reyes, interviewed in RadioLab, “Border Trilogy, Part 2: Hold the Line,” April 5, 2018.

Transcript: https://www.wnycstudios.org/story/border-trilogy-part-2-hold-line

[14]Ibid.

[15]Jeff Gammage, “The other side of the fence: Nations everywhere are building border walls, but do they work?” Philadelphia Daily News, 10 December 2018: 8.

[16]Anthropologist Jason De León wrote extensively on this subject in Land of Open Graves, a publication detailing his research into the fundamental difficulty of tracking accurate data for those who have died crossing illegally into the United States.

[17]United States General Accounting Office, Report to the Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate, and the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, “Illegal Immigration: Southwest Border Strategy Results Inconclusive; More Evaluation Needed,” December 1997, Appendix V, p 84. https://www.gao.gov/assets/230/224958.pdf

[18]Cristina de Middel, interview with the author, April 8, 2019.

[19]Carole Naggar and Fred Ritchin, Magnum Photobook: The Catalogue Raisonne. Phaidon Press, 2016, 16. Ritchin wrote this to describe the opportunities afforded Magnum photographers who published their work in long form books, but this can be used to describe any photoessay.