Brexit Britain: The Perfect Storm Facing British Farmers

Martin Parr documents the agricultural community in Wales as part of an ongoing project on Brexit Britain

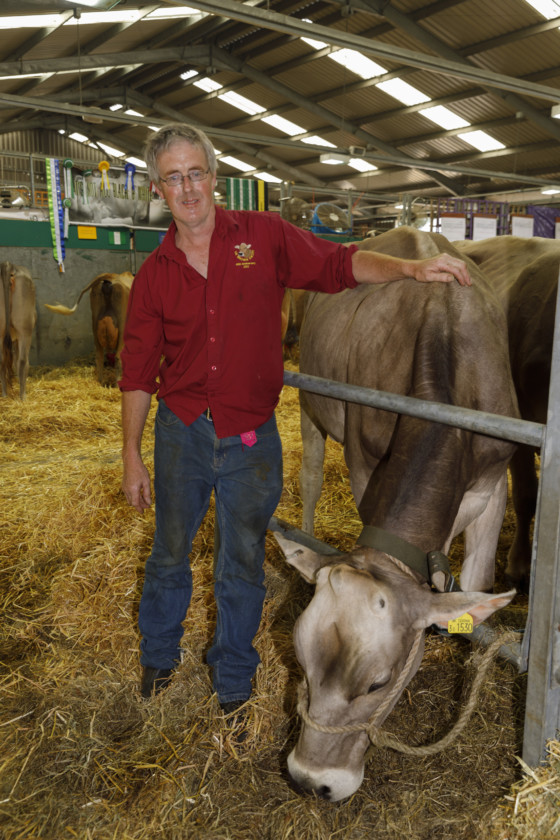

The Royal Welsh Show is winding down for another year. Red-faced farmers wrestle with unruly sheep as they battle for Best in Show, cows bask in the cool shade of the stables, while horses trot to attention. It’s business as usual for the agricultural fair, which has been running for over a century. Except this year, there’s a political undercurrent that is unavoidable—not least because Theresa May helicoptered in for the occasion.

“Everything was working quite well as it was; we’re stronger as a bigger collective,” says Remainer Bruce Ingram, who commands a flock of 3,000 sheep in Aberdeenshire and has just won first prize in the interbreed pair category for his Charollais ewe. “Europe has looked after us quite well and now we’re going to upset the apple cart,” adds his partner-in-show, Tim Pritchard, a small-scale sheep breeder from South Wales.

Photographer Martin Parr documented the RWS as part of an ongoing project on Britain in the time of Brexit. “These older professions are part of what is going on in the country right now; all of them are struggling,” he says. “I’m building up an archive about the British isles and every new thing I do contributes to that.”

The RWS is a chance for farmers to compete with world class livestock from across the UK but it’s also an opportunity to compare notes on their challenging profession and its rocky future. Louise Smith of Spath Farm in Uttoxeter voted Remain—unbeknownst to her husband who voted Leave—but didn’t make the decision easily. “I had no idea which way to vote,” she says. “I was torn right up until the end.”

Spath Farm breeds Simmental cattle and doesn’t benefit hugely from the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) payments that keep some farms afloat. “We’re paying in a lot of money and are bound by rules set by the Berne Convention that are not necessarily relevant to the UK,” Smith says. “For example we have a massive [bovine] TB problem here, we need to be spending money sorting that out and we’re not able to.” Despite this, she felt the safer option was to Remain but still has deep mistrust of politicians from both sides.

Peter Newth, a farmer from Gloucestershire who manages 60 beef cows, is in no doubt about the “stupidity” of Brexit. “Once the government stop the payments, which they will, we won’t be able to afford to keep the feed cheap and supermarkets will source from abroad,” he says. “I don’t think there’s any future in small farms. The 1,000 acre farm will be farming 3 or 4,000 acres in years to come because they have the kit and the buying power. The 150 acre farmer—unless they’re happy to work for basically nothing for their entire lifetime—will completely disappear.”

Deep in the valleys of a mid-Wales lamb farm, preparations are already being made for a predicted “perfect storm” post-Brexit. “We risk losing our export market, losing our support payments and the cost of production will go up because so much of our machinery, medicines and feed are imported. On top of that, Welsh Lamb is PGI [Protected Geographical Indicator] status and if we leave the EU we will almost certainly lose that, which is hugely valuable,” says farmer Rhodri Lloyd-Williams. “But maybe there’s a master plan no one’s told us about,” he adds unconvincingly.

Moelgolomen farm has been in the family for over 400 years. Its newest custodian, Lloyd Williams, 36, manages the 800 sheep and 25 cows with his 67-year-old father and wife Sarah, who part-times as a local GP. The farm has been organic since 1999 and as of 2013, weather permitting, runs entirely off-grid. The family even have an electric car which is powered from “the energy of the water that runs down the hill”.

Bucolic though it certainly is, the farm just breaks even on sales of stock—80 percent of which are exported to the EU—and most of their income comes from CAP payments, with a small amount from UK environmental schemes and maintenance for being organic. Post-Brexit, Michael Gove has promised to match CAP payments until 2022, after which small scale farmers may be facing economic abyss.

“All of a sudden the UK government will be deciding if we get these payments and we’ll be up against the NHS, the army, policing, education and so on,” he says. “We’re in a country where importing food is cheaper and so politically, farmers don’t have a lot of clout. The rural vote is not a big one and I don’t think there is the political will to help us out.”

This cornucopia of potential disasters makes it difficult to understand why any farmers voted to Leave. “Lies essentially,” says Lloyd-Williams. “Reading the wrong papers.” But it goes deeper than that. He explains how a lot of older farmers have a distaste for the EU because of the hoops they have to jump through to meet regulations. “Post-war, they were told; ‘Here’s the payment, go and farm as much as you can, the country is starving.’ And they spent every day doing what we as farmers love doing: being outside on the tractor with your dogs,” he says. “Now they’re spending 50 percent of the time sat in an office, filling out forms and keeping records and they hate it. They were told if we leave the EU all that will go. But it’s not going to.”

While older farmers may be looking to the past, Lloyd-Williams, who studied animal science and wildlife biology at university, is determined to forge a sustainable future. He set up a box-scheme in December 2017 that offers half or whole lambs, butchered in nearby Machynlleth and delivered directly to customers. It cuts out the middleman and generates up to 20 percent more profit than selling through supermarkets. “People actually come to pick up the boxes because they want to see the farm,” he says. “It’s about building a relationship with buyers.”

Meanwhile, an upscale tree house that sleeps four is nearing completion in one of their nearby fields. Designed by local architect Carwyn Lloyd Jones—famous for the Dragon’s Eye pod—it is being posited as a “digital detox in nature” complete with an outdoor shower and panoramic views. They have planning permission for four more and if farming doesn’t pan out, the Lloyd-Williams family can turn their hand at hospitality.

For enterprising farmers there is the potential to stay afloat through adaptability and diversification. But for others with less capacity for change, the future looks bleak. “Most farmers round here left school at 16 and started farming,” Lloyd-Williams says. “Their depth of knowledge of farming and the natural world is incredible but they don’t know anything else. If you take away farming from farms, these people are left with nothing.”