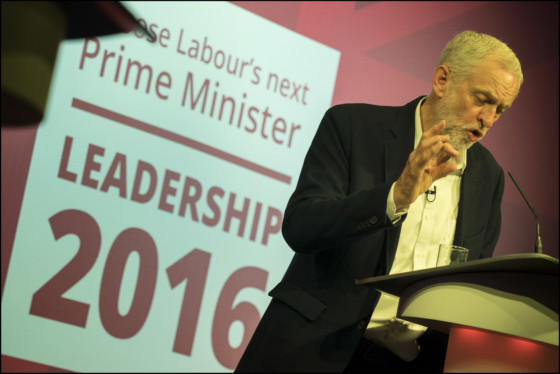

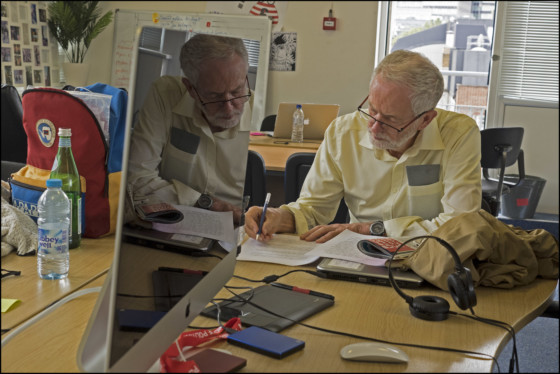

It’s been another summer in the trenches for the Labour party in the UK. Its two wings seem to be unable to tolerate one other. Vicious insults are traded online, the party has slumped in the polls, and many MPs and supporters fear a general election wipeout. Leader Jeremy Corbyn, for years a backbencher with little previous reason to leave his home city of London, has had a summer of trains across the country and being mobbed by fans searching for a selfie. Magnum’s Ian Berry was there to witness elements of this intense campaigning period, during which he also photographed award-winning British film director Ken Loach, who has been working on a promotional film for Corbyn.

Magnum was granted access to Corbyn via left wing grouping Momentum, which developed out of the 2015 Corbyn leadership campaign. It has formed much of the local activist base for the 2016 campaign, and includes past and current Labour party members. It encourages grass roots activism and galvanizes its efforts around seeking to “strengthen the Labour Party by increasing participation and engagement at local, regional and national levels” according to its mission statement.

James Schneider, a Momentum national organiser and head of rebuttal for the Jeremy for Labour campaign, says that Momentum exists in order to channel ‘the amazing energy and enthusiasm that came out of Corbyn’s last leadership campaign’, but according to critics, it has created ‘unnecessary division’ – the words of former Labour MP Tom Harris – and is not a “Labour-supporting organisation – it is a Corbyn-supporting one.”

Suspicion of Momentum amongst more centre-left Labour supporters is perhaps due to memories of divisive battles between the centre and far left that took place in the 1980s. But to paint all of Momentum’s 18,000-plus members as hard left belies the youthful enthusiasm that Corbyn has fostered since becoming leader, when he was apparently only afforded a place on the ballot due to the generosity of colleagues who had had no intention of voting for him (one of whom – Margaret Beckett – has since described herself as ‘a moron’ for doing so).

A veteran backbench rebel, Corbyn rebelled against Tony Blair and Gordon Brown’s Labour leadership over 400 times. His outspoken opposition to the Iraq War and university tuition fees made him an unlikely victor on the backs of returning members ill-at-ease with New Labour’s centrism and the young and idealistic, who were fed up with political orthodoxies.

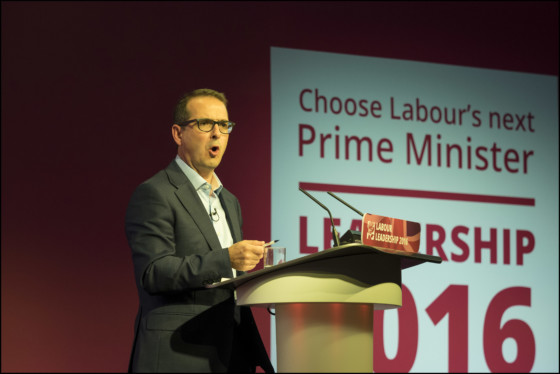

But the party mainstream has never truly taken to Corbyn and, after months of rumours, and in the wake of Britain’s vote to leave the EU, it accused the long-time Eurosceptic Corbyn of refusing to campaign properly. Corbyn weathered a string of frontbench resignations and an overwhelming vote of no confidence to remain party leader. Owen Smith, MP for Pontypridd, Wales, eventually emerged as a challenger.

Corbyn has had the support of the trades union movement, which traditionally has had some influence on the Labour Party. Unite (the largest trade union in the UK and Ireland) general secretary Len McCluskey has been unequivocal in his backing of the controversial left-winger, and another trade union, the Transport Salaried Staffs’ Association (TSSA), has donated office space to Momentum to work in. The official Corbyn campaign group is Jeremy for Leader, whose phone bank manned by volunteers was photographed by Matt Stuart.

Their rallies have attracted crowds of thousands and Corbyn’s campaign has been credited with increasing the youth appeal of Labour. According to Schneider this can be attributed to the younger demographic feeling disillusioned. He explains: “Young people need to see a large amount of change in society. They generally have far less money, fewer opportunities and less power.”

The growth of Corbyn’s brand of anti-politics is not unique within the western world. The insurgent left-wing group Syriza has effectively wiped out the Pasok in Greece, and Podemos has fractured the Spanish Socialist Workers Party vote in Spain. In America, the disaffected rallied behind Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, the former claiming the Republican presidential nomination, the latter running Hillary Clinton close for the Democrats.

Schneider credits the phenomenon to “a breakdown in the political, economic and social consensus that has governed in one form or another for 40 years”. What is clear is that an age of deference in the UK is coming to an end; what has replaced it is more idealistic, uncompromising and sometimes even abrasive.

This article is the first in the series ‘Modern States of Britain’, where Magnum Photos takes the current political temperature in the United Kingdom following the referendum vote to leave the EU.