Tipping Point: The 50th Anniversary of the 1968 Democratic National Convention Riots in Chicago

Magnum photographers documented the political and civil unrest that shook America over four days during August 1968

Magnum Photographers

“The whole world is watching,” chanted demonstrators as they poured onto Michigan Avenue to face violent resistance from Chicago’s police force on the evening of 28th August 1968. The ensuing riot marked the culmination of clashes between anti-Vietnam War protesters and the police during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The convention itself was pervaded by tensions as delegates voted for their Democratic nominee amidst debates about the Vietnam War and civil rights.

On the 50th anniversary of the 1968 DNC riots we look back at Magnum Photographers’ documentation of the unrest within, and outside of, the convention hall.

The 35th DNC took place in Chicago’s International Amphitheater from 26th to 29th August 1968. Delegates flocked to the city to select their Democratic nominee but tensions were high. “There was violence inside the International Amphitheater before violence broke out in the Chicago streets,” wrote Arthur Miller, who attended the convention as Connecticut delegate running for leader, Eugene McCarthy, in his essay The Battle of Chicago: From the Delegate’s Side.

The convention followed a string of events that had caused deep divisions within the Democratic party. In March of that year, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced he would not seek re-election; three months later, presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. Kennedy had been a staunch supporter of civil rights and ending the Vietnam War; now it was unclear who his followers would endorse.

In the lead-up to the convention, support within the party was divided between Hubert Humphrey, Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern. While Humphrey espoused the views of President Johnson, who publicly stated his determination to win the war, McCarthy’s campaign was dominated by his determination to end America’s involvement in Vietnam. These divisions were reflected on the convention hall floor. Burt Glinn and Raymond Depardon documented the heated atmosphere.

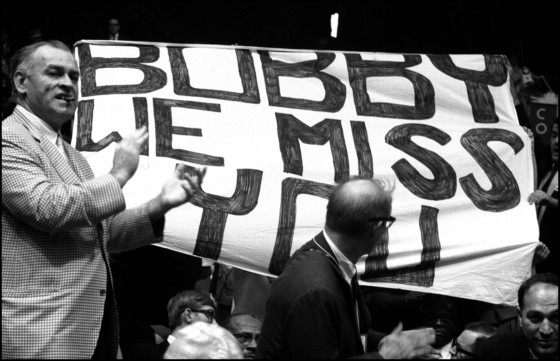

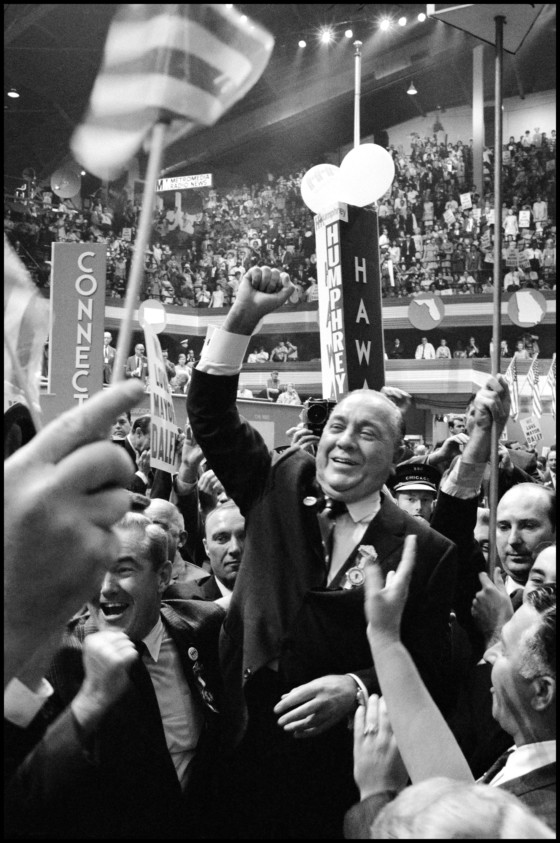

In an image by Glinn delegates clutch a banner that reads “Bobby we miss you,” while in another, by Depardon, Humphrey supporters manically wave posters and flags at the camera. Fierce debates over issues including the Vietnam War and civil rights rapidly escalated into violence, with the arrests of delegates and beatings of journalists.

"The sound of battle was heard long before delegates gathered"

- Mitchel Levitas

The issues under discussion at the convention itself were the same that had drawn several thousand protesters to the city. “The sound of battle was heard long before delegates gathered for the 35th Democratic National Convention,” observed Mitchel Levitas in his essay Political Response, published in America in Crisis, 1969. 1968 was a year of uprisings and unrest across America, but also around the world. In particular, civil unrest concerning the Vietnam War had intensified in the months leading up to the DNC.

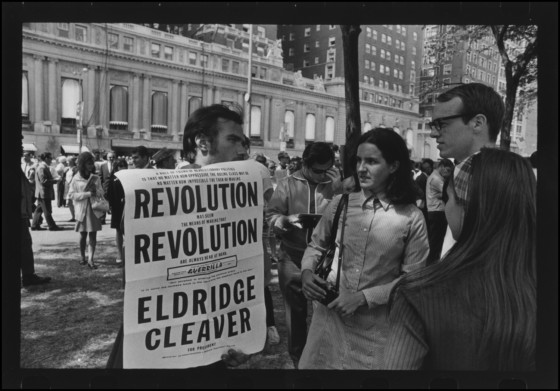

In January 1968, the Tet Offensive – a massive onslaught launched by North Vietnamese forces in which the South and the U.S. sustained heavy losses – tipped public opinion about the seemingly endless war. The extensive media coverage it received was unprecedented, opening Americans’ eyes to the reality of the war and accelerating anti-war sentiment as a result. Photographs by W. Eugene Smith, Constantine Manos, and Wayne Miller document myriad anti-Vietnam war protests that took place across the country during the following months.

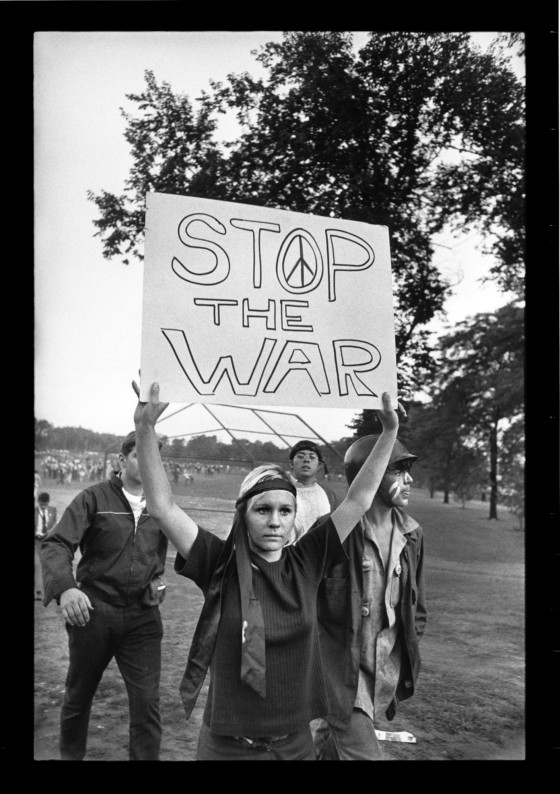

Additionally, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King on 4th April 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, worked to add fuel to the civil rights movement and was followed by weeks of rioting and rebellion. The National Mobilization Committee to end the War in Vietnam (the Mobe) and the Youth International Party (Yippies), two leading anti-Vietnam war groups, saw the convention as an opportunity to draw attention to these issues and planned a series of protests across the city.

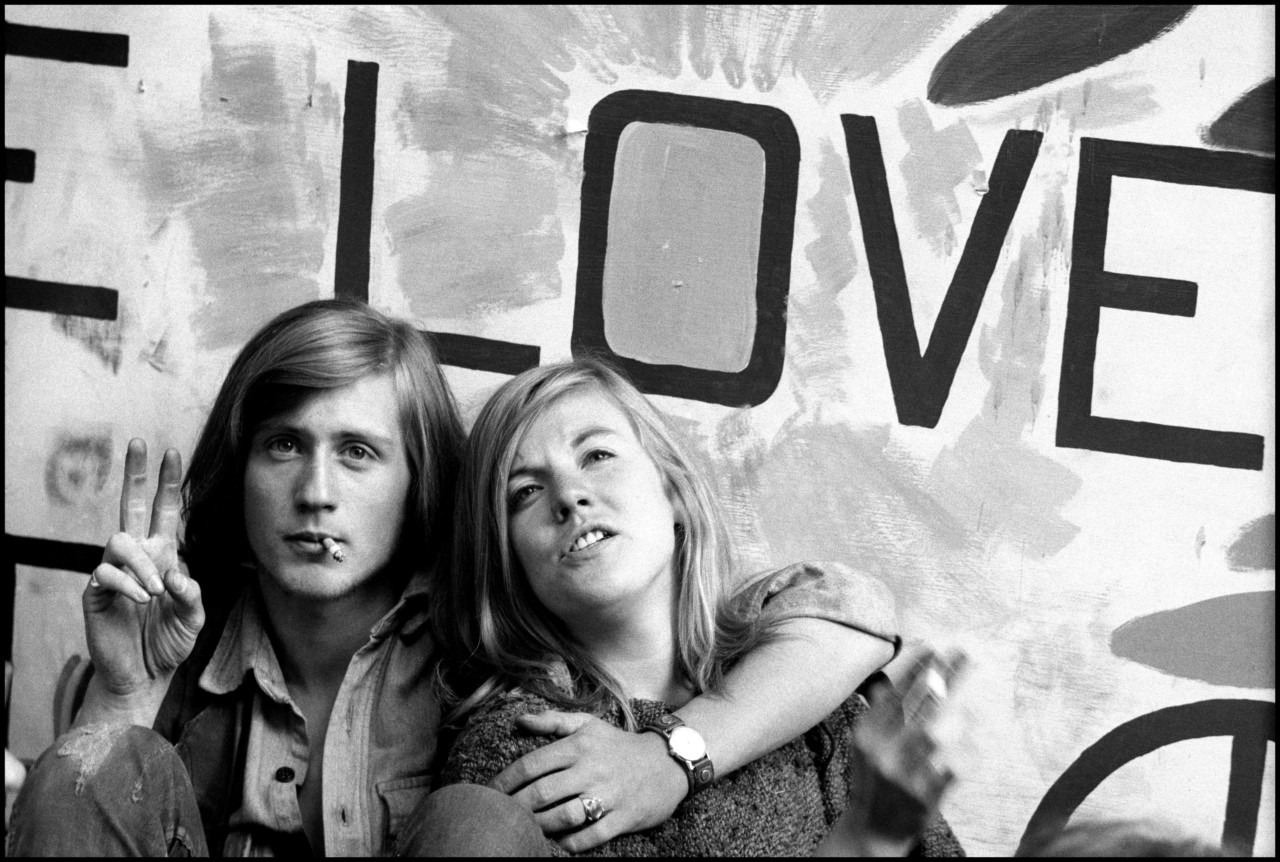

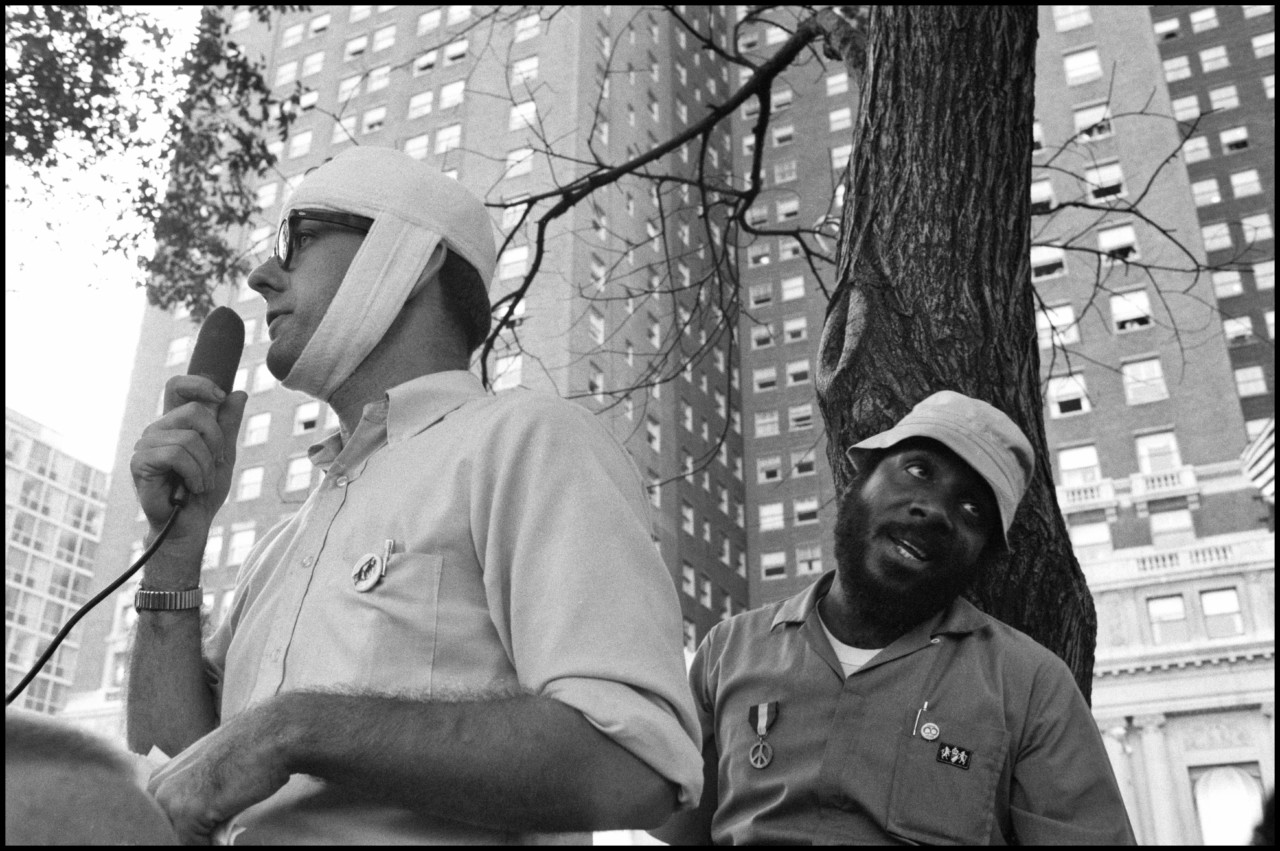

Demonstrators arrived brandishing placards and banners demanding the end of the Vietnam War and civil rights abuses. Among them were the French writer Jean Genet and American writer William S. Burroughs, both on assignment for Esquire, and the American poet Allen Ginsberg, whom Depardon photographed as they took part in an anti-war protest in Chicago’s Grant Park. Glinn also photographed outside the convention. In one image he captures two young protesters resting against a placard, while others depict animated speakers, including the American actor and activist Dick Gregory, addressing the crowds.

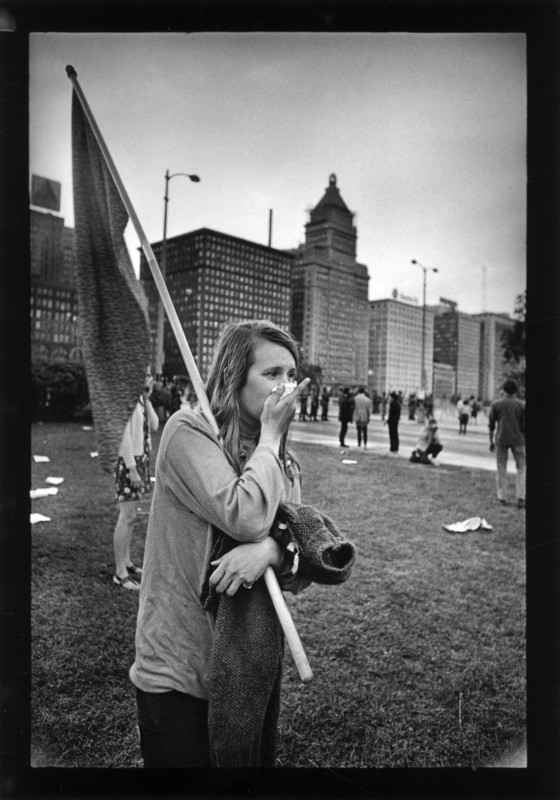

But, echoing the chaos on the floor of the convention, the demonstration rapidly dissolved into violent clashes between police and protesters. Aware of the tense political atmosphere and determined to prevent any further uprisings like those that had rocked the city following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King months earlier, Chicago’s Mayor Richard Daley had imposed tough sanctions that permitted the police to respond with force in the case of any future disturbances.

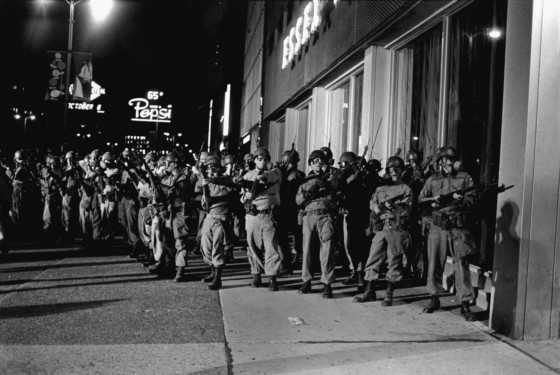

The majority of clashes took place in Lincoln Park, where the protesters had established their base, and later, also in nearby Grant Park. “It was the clearing of the demonstrators from Lincoln Park that led directly to the violence: symbolically, it expressed the city’s opposition to the protesters,” stated the Walker Report, an in-depth federally sponsored investigation into the events, which concluded that what took place could “only be called a police riot”. Glinn and Depardon documented the ensuing violence, which saw over 12,000 police officers, and another 15,000 state and federal officers, forcibly contain and resist the almost 10,000 protesters who had descended upon the city.

"It was the clearing of the demonstrators from Lincoln Park that led directly to the violence"

- Walker Report

Depardon’s iconic image of a smiling woman gently approaching a line of police, sporting crash helmets and holding guns, speaks of the majority of protesters’ peaceful intentions. Although officers were subject to verbal and physical provocations by some demonstrators, the unrestrained and indiscriminate level of force with which they responded shocked audiences across the country as events played out on television broadcasts. As the violence escalated, civilians, journalists and delegates were also caught up in the riots.

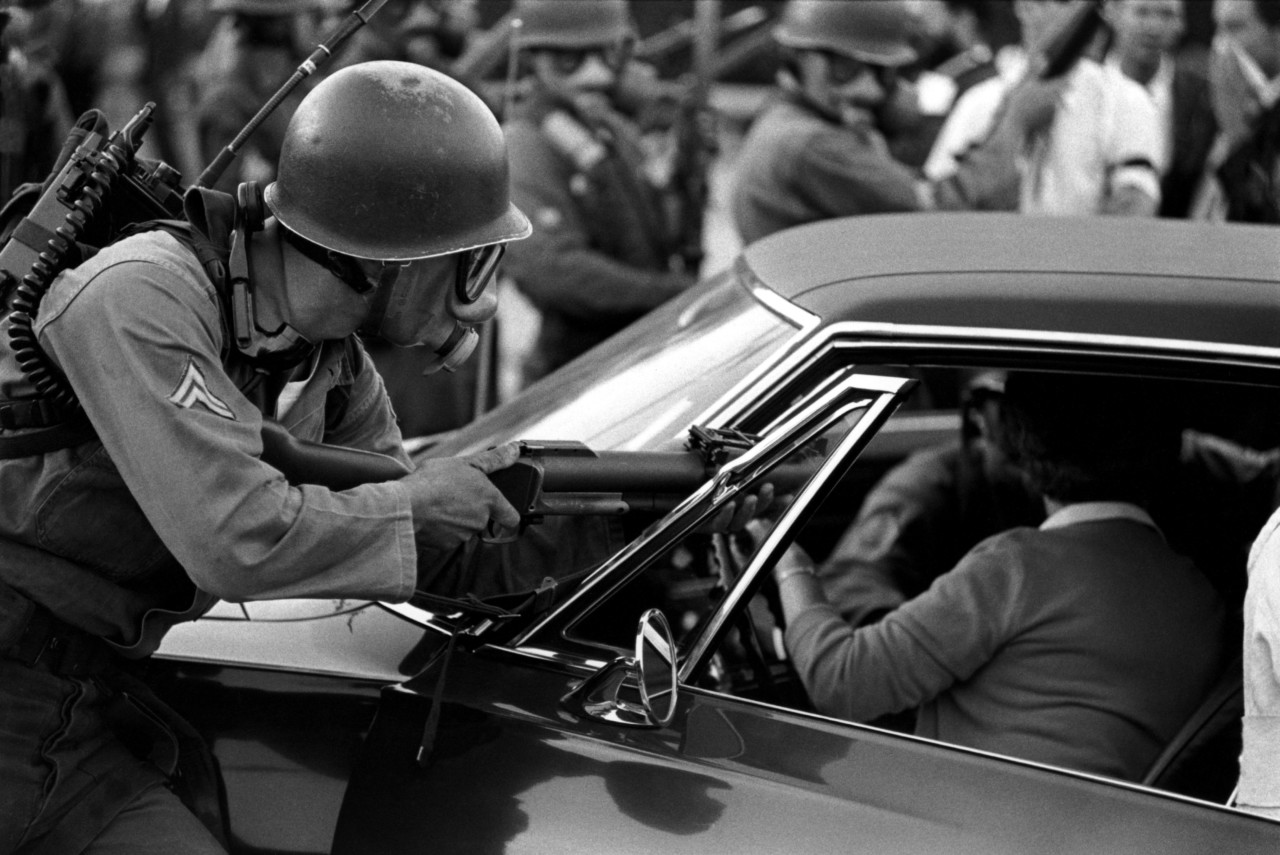

In one photograph by Depardon, a heavily armed officer, his face obscured by a gas mask, can be seen driving his gun through the window of a moving car; another image depicts a wall of heavily armed police advancing up an eerily desolate street.

The occupants of the convention hall were far from oblivious to the carnage engulfing Chicago. Daley – who had been a central force in bringing the convention to the city – was present and had filled the balconies with his supporters. Glinn photographed the Mayor with his fist raised, chastising the anti-war protesters who the police were violently repressing outside. However, other delegates were critical of the situation. Connecticut Senator Abraham Ribicoff famously used his nominating speech for McGovern to condemn the violence; Arthur Miller remembers partaking in a march with other delegates past the carnage in solidarity with the demonstrators.

Chicago was a pivotal moment in American political discourse, where the flashpoint surrounding the DNC had wider implications for America. The convention acted to deepen divisions within the Democrat party. Many believed that President Johnson and Daley had influenced the vote in favour of Humphrey, who was selected as the Democratic nominee and went on to lose the election to the Republican candidate, Richard Nixon.

Although polls indicated that the majority of Americans were sympathetic towards the police, the riots were emblematic of the tensions between the authorities and civilians, which had been mounting across the country for months. Ultimately, the event galvanized the protest movement and exacerbated the drive for political reform.