Fighting for Free Speech in Ethiopia

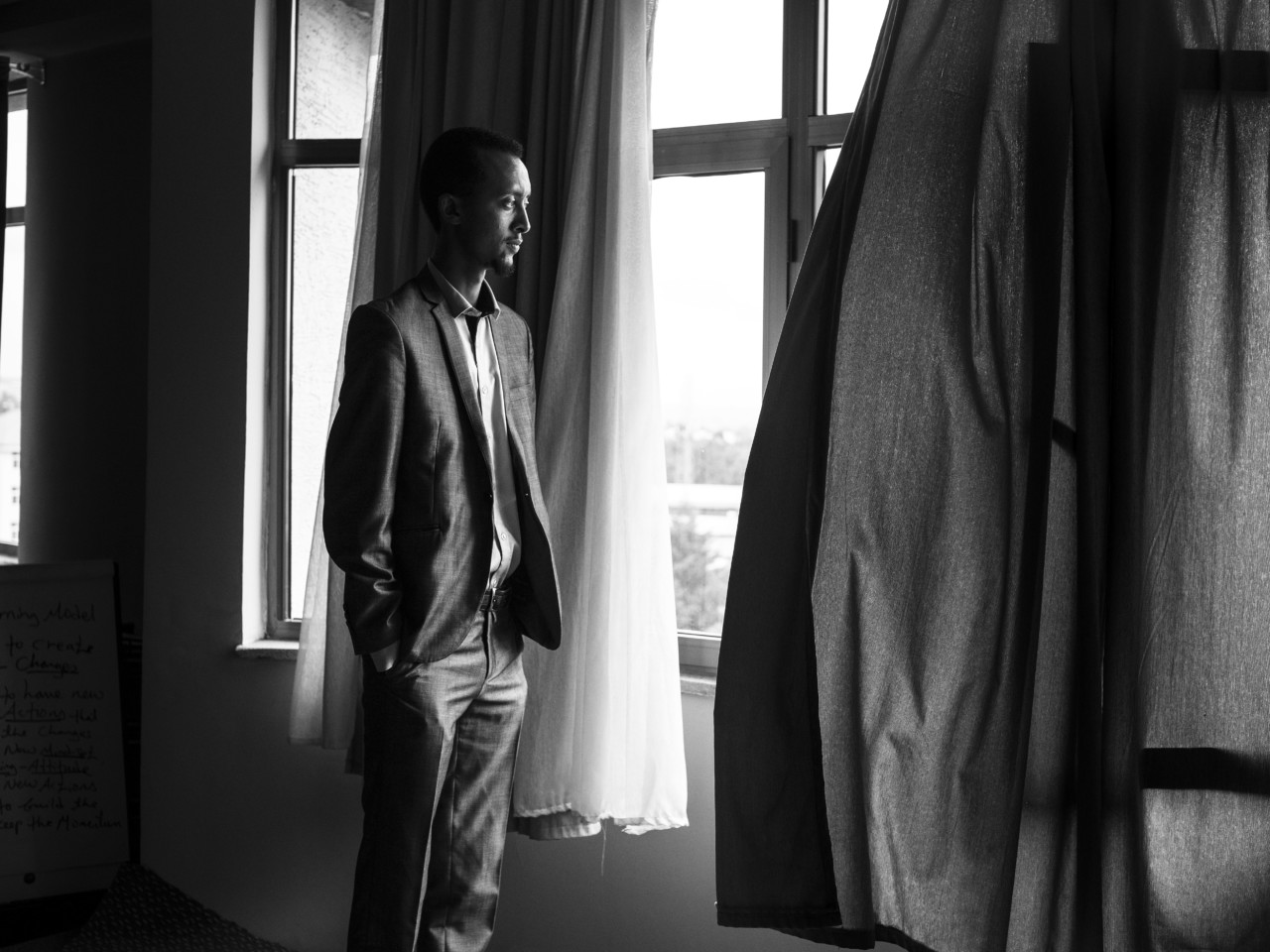

Enri Canaj follows Ameha Mekonnen, a 45-year-old lawyer battling the Ethiopian government to protect human rights

To mark 30 years of the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought — an annual prize established by the European Parliament to pay tribute to human rights work — Magnum photographers have worked with the European Parliament for a book of writings on human rights and the people fighting for them today, as well as an exhibition launching this month.

Although it was difficult to photograph him publicly, Albanian photographer Enri Canaj highlighted the work of Ameha Mekonnen, a former civil servant turned lawyer in Ethiopia. He advocates for journalists facing censorship from government authorities. (Ethiopia is an authoritarian state ruled since 1991 by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front and in 2016, hundreds of people were killed in a crackdown on antigovernment protests.) Canaj followed Mekonnen as he met with clients who face imprisonment for what they publish.

Terror reigns in Ethiopia. For 25 years, the ruling coalition has been violating human rights in the same way that Colonel Mengistu and his junta did during the ‘Red Terror’ of his Marxist-Leninist dictatorship in the late 1980s.

This suffocating climate, this all-encompassing dread and this feeling of constantly being followed, overheard and under threat is part of daily life for Ameha Mekonnen, a 45-year-old lawyer.

He has been waging a lone, or almost lone, battle. In Ethiopia, few people are fighting to protect freedoms that the authoritarian regime will not even contemplate granting: freedom of thought, freedom of expression and freedom to criticize, to demonstrate and to object. Mekonnen is totally innocent, and yet there are only four places he feels safe: in his car, in his office at the Human Rights Council — the only independent human rights organization in Ethiopia, at a family hotel in Addis Ababa, and lastly at home with his family — his wife, who is also a lawyer, and his two daughters aged seven and four.

The Albanian photographer Enri Canaj, who spent six days with Mekonnen, witnessed the risks inherent in his work. “I wanted to show the hope he embodies for everyone he defends and gets out of prison — the bloggers and the journalists. It was amazingly invigorating to see him in action. But I also wanted to show his everyday life, his daily struggle and the difficulties that arise. By helping people in danger, he places himself in danger.”

Canaj was unable to work as he would have wished. He had to make do with photographing Mekonnen indoors and in his car. Taking pictures in public was out of the question. Both men spoke very little on the phone and maintained discreet contact. Mekonnen was very worried. As was Canaj, who had to conceal the real reason why he was in Ethiopia; he even considered saying he had come to photograph wildlife. Mekonnen described how he had recently organized a fundraising event for his organization at a hotel in Addis Ababa. The event was all set to start when the police burst in and stopped everything.

Despite all this, Mekonnen makes no attempt to hide from the authorities, which earned him Canaj’s admiration. Canaj was able to meet five of the nine bloggers and journalists who had spent over 1 year in prison. Mekonnen had secured their release, but they had no jobs and thus could no longer support themselves. No one wanted to employ them, even if the charges of terrorism brought against them were false — the regime does not look kindly on people who extend a helping hand to these former prisoners. The group told the photographer about the terrible prison conditions and cramped, suffocating cells.

Mekonnen also introduced Canaj to a young woman blogger from the Zone 9 group who had been imprisoned for 14 months and mistreated. “Mekonnen decided to immediately act as her lawyer,” says the photographer. “He thought of his daughters and could not bear the thought of the same thing happening to them one day. His family is a pillar of strength and what motivates him to work with such fervor. I also wanted to portray all that in my photos: his courage, his values and his dedication as a lawyer, but also his devotion as a father.”

While Canaj was frustrated at being unable to capture stunning shots of Mekonnen for security reasons, there was one incident that lingers in his memory. One day, as Mekonnen was on his way to meet fellow committee members, the lift broke down. He always walks with a cane and had to go up the stairs slowly, step by step, with the end of his cane striking the floor. “It was a perfect metaphor for his battle for human rights.”

To say that Mekonnen is courageous in his defense of human rights would be an understatement. Ethiopia has been in the grip of unrest and bloody repression since November 2015, with power lying in the hands of the Tigrayans, who are an ethnic minority in the country. The Oromo, who are the ethnic majority, oppose the expropriation of their lands in the interests of foreign companies. The government has sometimes responded with violence, which, according to Amnesty International figures, has left 800 people dead with thousands of demonstrators arbitrarily arrested and detained.

The situation has deteriorated since October 9, 2016, when the government declared a state of emergency. That state of emergency was renewed in March 2017 before being lifted on 4 August. Prior to that, almost 30,000 people were arrested, including many journalists and opposition leaders. The few activists who speak to the press strive to remain anonymous, while the former prisoners find their degrading treatment hard to forget.

“Not content with hitting us, the police forced us to crawl like snakes on gravel, to stare at the sun and to jump like kangaroos for hundreds of meters with our feet tied together,” wrote the Ethiopian blogger Seyoum Teshome, as reported by Émeline Wuilbercq in Le Monde Afrique on May 26, 2017. Their crimes? Denouncing corruption at the highest level and protesting against the trading of land to the detriment of people already excluded from a share in the country’s wealth, as well as against blatant inequalities and the deterioration of living conditions for the very poor.

While critical of the government, Mekonnen refuses to attack it along the lines of the ethnic antagonism that exists between the ruling Tigrayans and the other ethnic groups. “That approach is contrary to my beliefs,” he stresses. “I see the people and the governing party as two separate entities.”

This highly committed man is walking a tightrope. Behind his genuine humility — “there are many other human rights defenders whose names should be put forward before mine” — lies a tenacity that means he does not shrink an inch in the face of intimidation and threats.

He states his beliefs clearly and directly: “I am fighting for freedom of expression. What is happening here in Ethiopia is very serious. There is nothing at all wrong with our constitution in terms of human rights. But our government sees no need to abide by that constitution! The members of our organization are constantly harassed, and three of them are regularly thrown into prison. Terrorism is given a broader definition in Ethiopia than anywhere else I know in the world. Those in power view each and every one of us as a terrorist! That includes journalists and opposition leaders whose only offence is to have stated opinions that conflict with those of the government. I could also end up in prison simply for speaking with you. I live under constant threat, but that does not stop me from speaking out in public to denounce wrongdoing. The work I do goes beyond what a lawyer would normally do. I am adamant that any infringement of human rights should be public knowledge.”

Mekonnen is completely clear-headed. He has all the facts at his fingertips and is constantly playing the ringmaster to the government’s lion in defending his clients — most of whom are in prison. He visits them there and works tirelessly to ensure their rights are respected. Some of the prisoners are from Germany, Norway and the United Kingdom.

Nothing would be possible without the Human Rights Council, which despite its very limited resources, has three lawyers among its permanent staff of five. “What I do is legal work,” says Mekonnen, “but I don’t take a meek approach to upholding my clients’ rights.” This is a euphemism for saying that his ‘full-on’ approach is likely to put him in great peril someday. Until then, he will carry on. That is his mission in life. His raison d’être is to ensure that no one dies in fear or despair in Ethiopia, that no one dies through ill-treatment or for arbitrary reasons and that no one dies for their views.

Mekonnen’s commitment to upholding fundamental rights was forged in 2006. At the time he was a lawyer in the service of the government. One day, the government decided to punish a leading professor for remarks he had made to his students. Mekonnen refused to toe the line. His reluctance to do so brought retaliation and many problems: He was banned from completing his legal training and acquiring a master’s degree. He had made up his mind. He left his job in order to entirely devote his energies to defending people charged with ‘crimes of opinion.

“I am not politically motivated,” he explains. “There are currently 36 people accused of terrorism who are depending on me. At the Human Rights Council, where I work as a volunteer, I am responsible for three areas: the fundraising committee, the committee responsible for external relations and the committee for human rights education.”

Despite his responsibilities, he is always calm and relaxed when at home with his family. He sees his country’s future in his daughters’ eyes. It is a future he wishes to be peaceful, calm and joyful. “I am full of hope. That is why I am staying in Ethiopia,” he says, and then repeats: “I do not deserve this recognition.”

See the stories from this series here.