Gerda Taro: The First Woman War Photographer to Die in the Field

We chart Taro’s remarkable career and her historic coverage of the Spanish Civil War.

On 1 August 1937, thousands of people lined the streets of Paris to mourn the death of photojournalist Gerda Taro (1910–1937): a 26-year-old Jewish émigré from Leipzig, Germany. Taro had died in Spain, while covering the Battle of Brunete, during the second year of the Spanish Civil War. Taro was a celebrated photographer and the first female photojournalist to be killed on the frontline.

Taro was eulogized as a courageous reporter who had sacrificed her life to bear witness to the suffering of civilians and troops during the Spanish Civil War. The media proclaimed her a left-wing heroine, a martyr of the anti-fascist cause and a role model for young women everywhere.

But, in the years that followed Taro slipped into obscurity. It was only years later that Taro was fully-appreciated as a photojournalist in her own right. In 2007, the International Center of Photography in New York opened the first retrospective of Taro’s work. Three years later, the exhibition and accompanying catalogue of the “Mexican Suitcase” of negatives from the Spanish Civil War by Taro, Robert Capa, and Chim added almost one thousand new images to Taro’s career.

Taro was born Gerta Pohorylle to a middle-class Jewish family in 1910 and grew up in the industrial city of Stuttgart in southern Germany. Her parents, who were originally from Galicia, had emigrated to Germany during the First World War. Taro attended a prestigious all-girls school where she excelled. However, in the summer of 1929 her father’s business failed, in part due to the worsening economic climate of the Weimar Republic, and the family relocated to Leipzig to start anew.

Anti-Semitism intensified as Germany descended into economic, social and political chaos. Taro was painfully aware of the rise of the far-right and became involved in left-wing politics. In March 1933, the National Socialists established control and Taro was arrested after distributing anti-Nazi leaflets around Leipzig. Soon after, encouraged by her parents and following in the footsteps of many of her friends, she fled to France – one of the thousands of political and intellectual exiles seeking refuge in the country.

It was here, in Paris, that she met Robert Capa when he was still André Friedmann: impoverished and, struggling professionally. Capa was an émigré too. He had arrived a few months earlier from his native Hungary to escape its repressive, anti-Semitic political regime. Both experienced similar hardship, struggling to survive in a city that was becoming increasingly saturated by, and hostile towards, its growing émigré population.

Capa’s career was in its infancy. He had achieved a small amount of success in Berlin, which was at the heart of the photographic revolution. However, in Paris, he struggled. In the summer of 1934, the photographer took on a job for a Swiss insurance brochure; the commission required him to find a blonde, blue-eyed model. He spotted Ruth Cerf, a friend and roommate of Taro, at a cafe and she reluctantly agreed to model. Taro, who accompanied Cerf, immediately warmed to the disheveled photographer. She was fascinated by his profession and, on seeing Capa’s work, convinced of his brilliance.

Before long the two were inseparable: first as friends and then as lovers. Taro advised Capa on his poor presentation and professional demeanor, while he encouraged her to experiment with photography. She soon developed an interest in the medium and, by February 1936, had become an accredited member of the press. However, despite their efforts, the duo struggled to make ends meet. Paris was beginning to overtake Berlin as the center of modern photojournalism; the competition for work and recognition was intense. The pair’s poverty, obscurity, and foreignness were holding them back and their names – Friedmann and Pohorylle – immediately branded them as immigrants and Jews. Taro realized this and together they both changed their names. He took on the alias of Robert Capa, who he imagined as a rich and successful American photographer, and she changed her name to Gerda Taro.

The plan worked: under the guise of Capa, his pictures began to sell. In April 1936, the pair could afford a room in a hotel on the western side of the Jardin du Luxembourg. It was as Capa and Taro that they traveled to Spain that same year to cover the resistance to General Franco’s fascist rebellion. The Spanish civil war represented an attack by the forces of fascism on the country’s democratically-elected Republican government and, galvanized by their own experiences, they were compelled to document it.

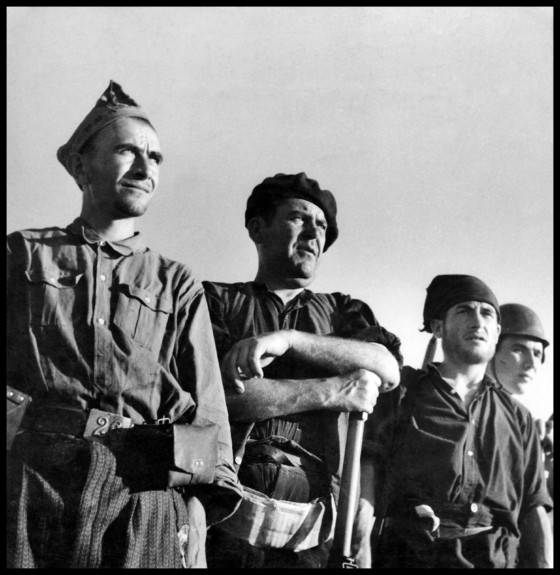

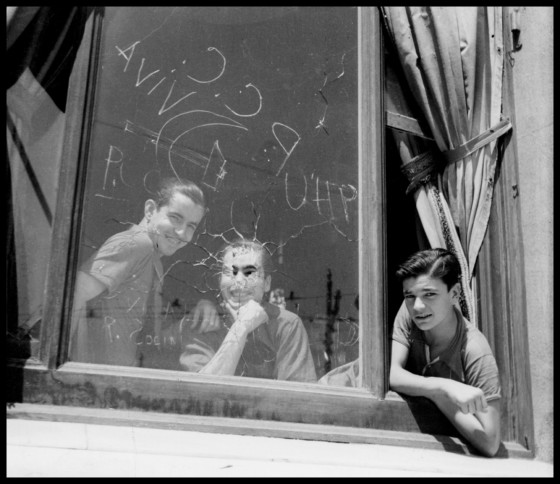

The couple arrived in Barcelona on 5 August 1936, two-and-a-half weeks after the outbreak of war. Taro had never been to Spain and the atmosphere, in these early days, was electric. One of their first stories was to document a group of militiawomen, who were members of the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (the Catalan branch of the Communist Party of Spain), training on a nearby beach. To see these women dressed in overalls and armed with guns in what was a highly-conservative society was unique. In one image, Taro captures a young militia member, wearing heels and crouched down on one knee, aiming a pistol into the distance.

Over the course of a year, Taro would return to Spain multiple times, often in the company of Capa but also alone. As she gradually established a reputation the photographer slowly distanced herself professionally from Capa and his growing success.

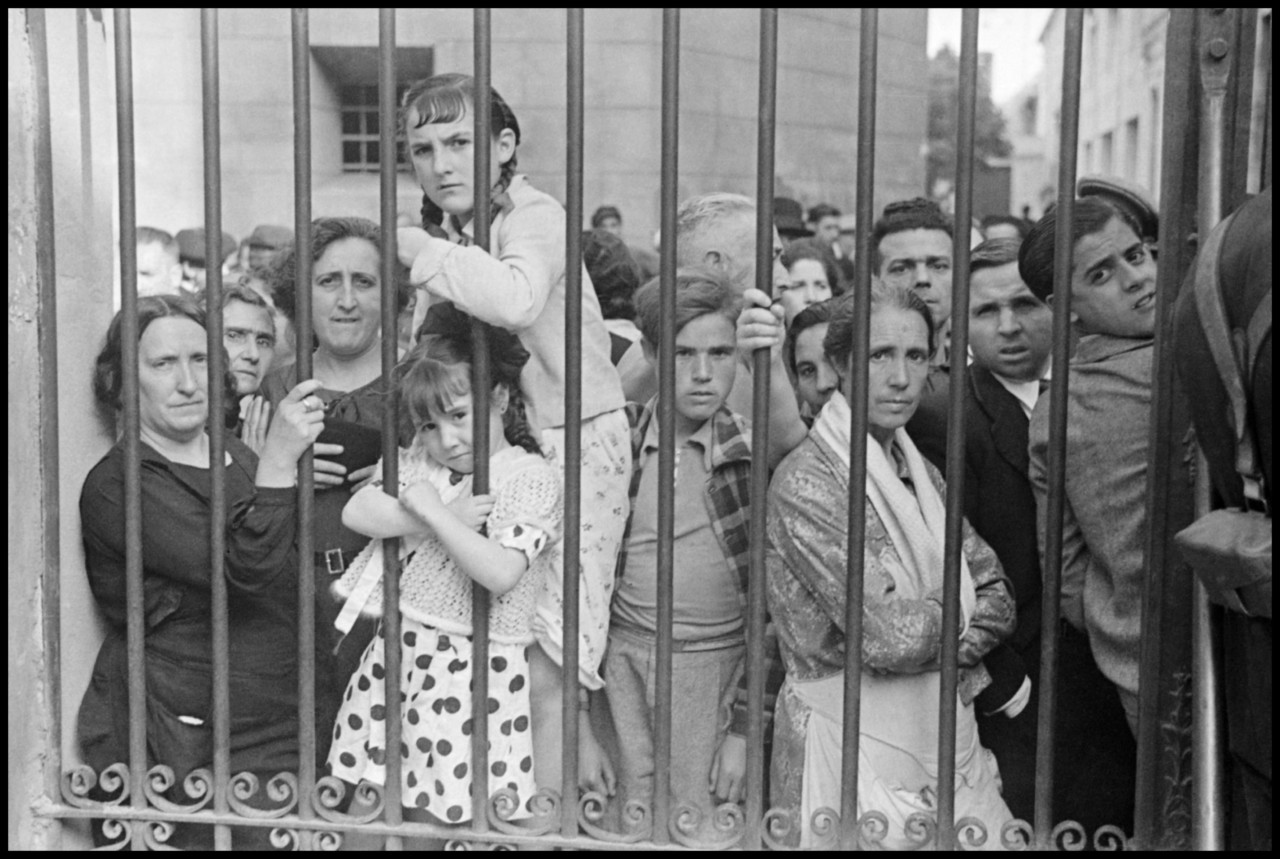

Travelling across the country, Taro bore witness to the suffering of the civilian population and the realities of life for soldiers on the frontline. In February 1937, she journeyed with Capa to the Andalusian coast to cover the thousands of civilians fleeing a nationalist advance on the southern city of Malaga. The French title Regards ran a number of her images and the story was credited to “Capa et Taro”.

"She threw herself into the heart of the action, compelled to experience the conflict first-hand."

-

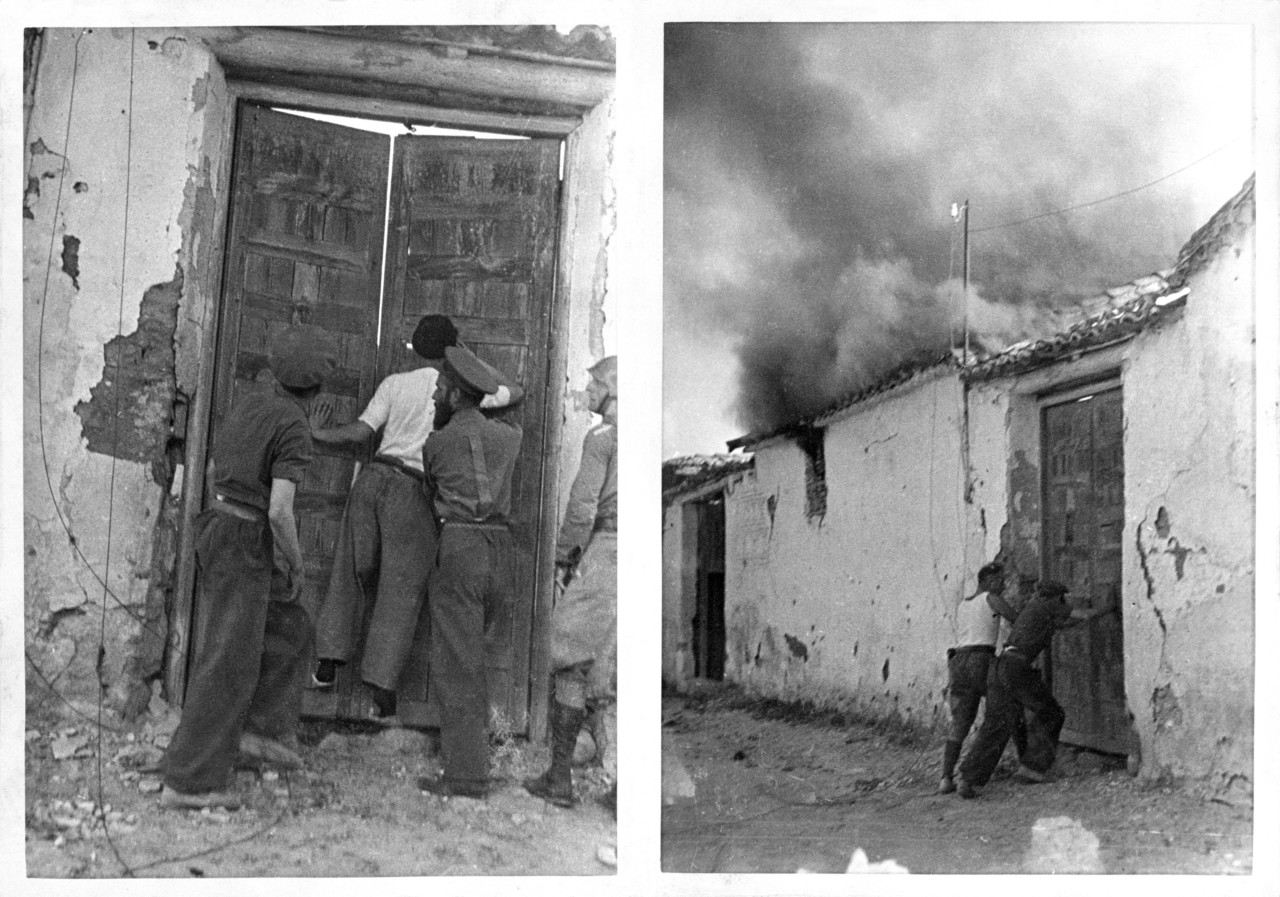

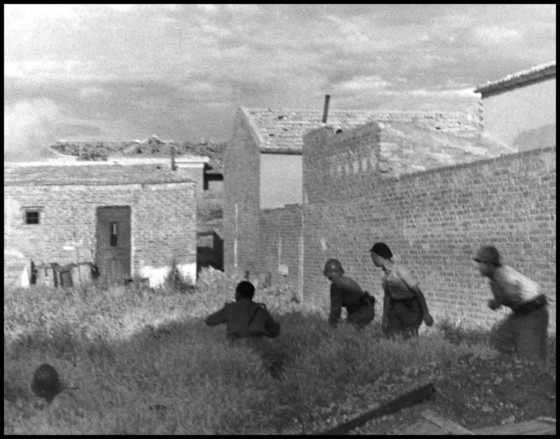

Taro was motivated by a desire to raise awareness of the plight of Spanish civilians and the soldiers fighting for liberty. Her affinity to those she was documenting is evident in her work; the longer she spent in Spain, the deeper she embedded in the conflict. In May 1937, Taro produced a series of haunting photographs that capture the terrified civilian population who endured the nightly bombardments of Valencia. Two months later Taro documented the biggest republican offensive yet: The Battle of Brunete. She threw herself into the heart of the action, compelled to experience the conflict first-hand. The experience sealed her reputation as a photojournalist but it also marked the end of her remarkable career. On 26 July 1937, Taro was wounded by an out-of-control tank while hitching a lift back from the front; she died the following day in hospital from her injuries. Despite having worked for less than a year, she left an indelible mark on the history of war photography.