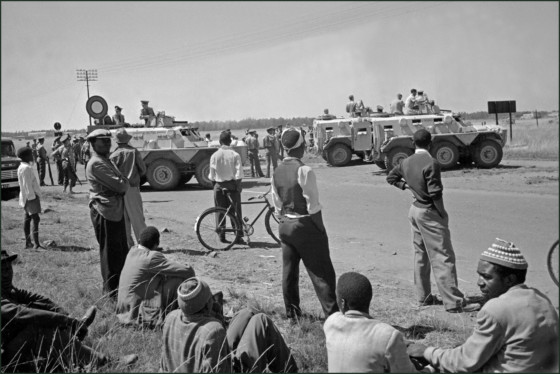

On March 21, 1960, at a police station in the South African township of Sharpeville in Transvaal (now part of Gauteng), following a day of demonstrations, police opened fire on a crowd of around 5,000 to 7,000 protestors. The crowds had gathered to protest pass laws, a form of internal passport system designed to segregate the population during apartheid. Although some reports described flare-ups and disturbances in the crowd, others state that the crowds were peaceful. Two years before he’d be invited to join Magnum, British photographer Ian Berry was present, and described the gathering as uneventful prior to the police opening fire.

Berry was working for South African magazine Drum when his editor called him on his day off to suggest he went to the black township of Sharpeville as there had been reports that somebody had been shot. He and a sub editor for the magazine, Humphrey, headed off to the area, where other members of the press were also arriving. At the gates, guards told them that without a pass they would have to vacate the area. But, knowing the area better than foreign visitors would, and having worked for a lot of African press, Ian Berry opted to stay there.

At first it seemed as if nothing much was happening, but Berry describes how the quiet scene erupted: “We came to the police station which was a building surrounded by wire with a large compound front. I told Humphrey to go around to the back of the police station and to park out of sight, and I would go and have a look. I walked into the crowd, who were all pressed up against the wire, and chatted with them; they were all friendly. Nothing was happening…. I walked back to the car, really intending to tell Humphrey that I didn’t think anything was going to happen and we might as well shove off. Just as I walked beyond the car I looked back at the police station – you know the final check that you always do before you leave – and the shooting started.”

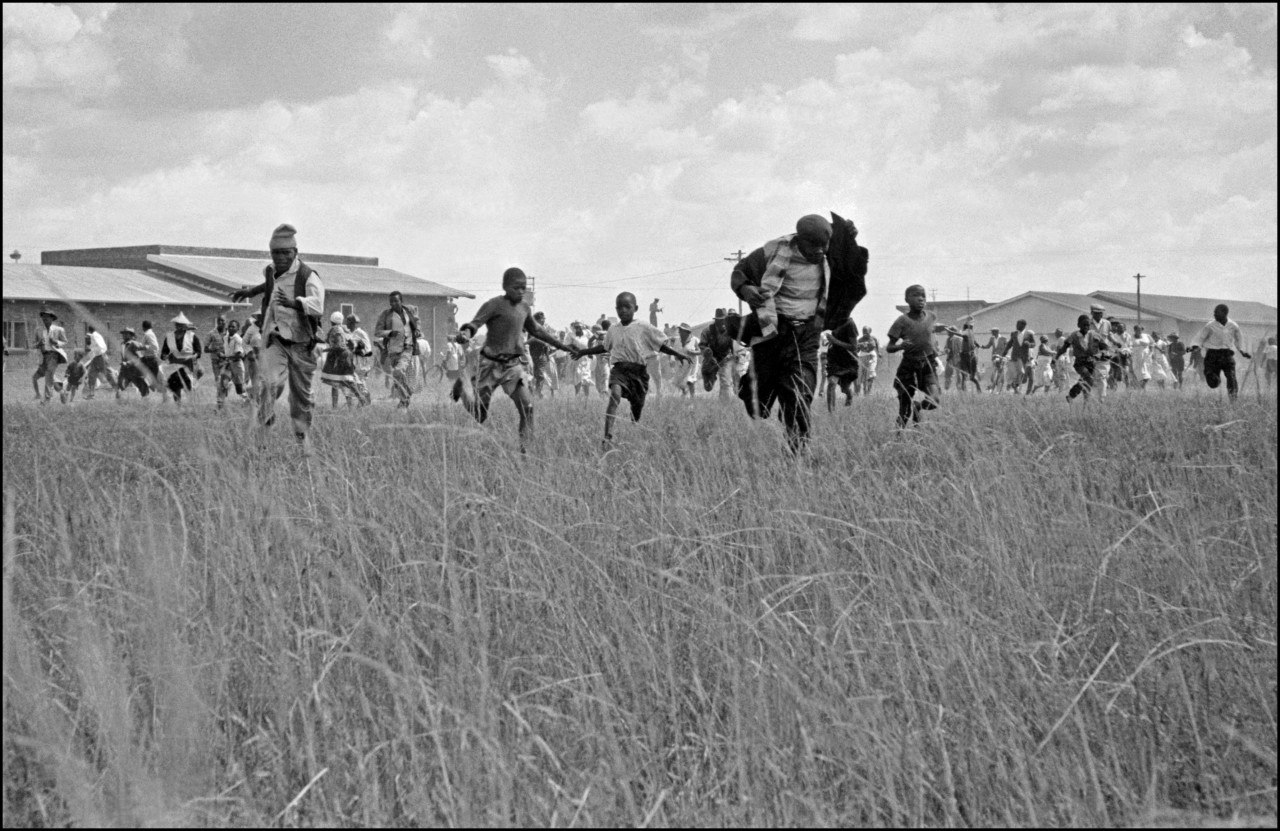

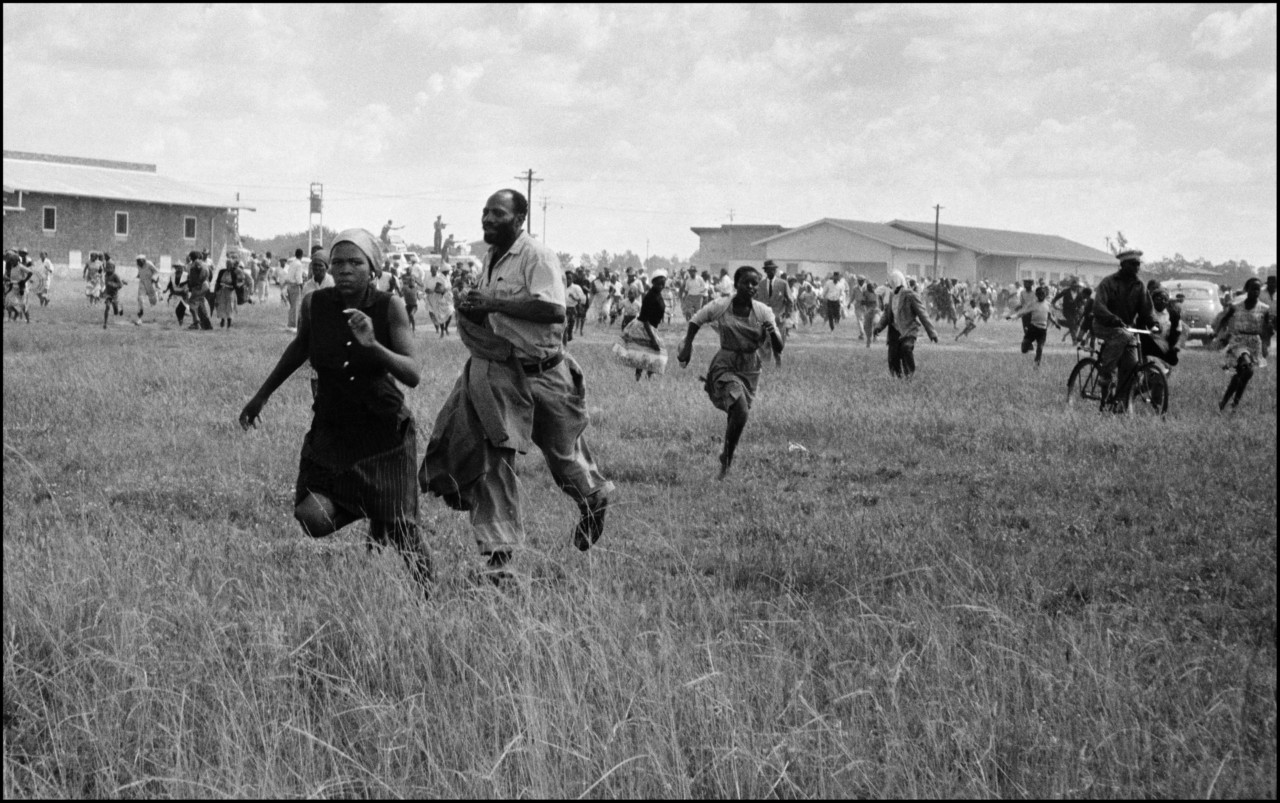

“I thought at first that they were either firing blanks or they were firing over people’s heads to disperse them,” he said. “It was only when a woman who was standing next to me fell on the ground that I realised they were actually shooting bullets. I, myself, got down on the ground quickly and shot the crowd running away in every direction.”

"Just as I walked beyond the car I looked back at the police station – you know the final check that you always do before you leave – and the shooting started"

- Ian Berry

Using a handful of 35mm cameras with both a wide angle and a prime lens, Berry snapped what he could, including a photograph of a man holding up his jacket to shield himself from the oncoming slew of bullets. “Shooting stopped once. I was about to get up, and it started again. When the shooting stopped, I was the only person still standing in the field. I thought this was not a good plan because the cops had offered to shoot me in the past as a photographer. I ran back to the car and we took off,” recalled Berry.

South African police had opened fire on the crowd, killing, it would transpire, 69 people, with 289 casualties in total, including 29 children. Many of those injured sustained back injuries from being shot from behind as they tried to flee.

Other than the testimonies of the police and the people of the township, the photographs were the only record of what had happened, the significance of which was evident to the magazine’s publisher. “The magazine owner, and this is a long story I won’t go into, refused to use the pictures in the magazine in case he got closed down,” said Berry. So at the suggestion of editor Tom Hopkinson, the pictures were filed to and distributed by an agency in London.

While the pictures were picked up by the international press, such as LIFE and Paris Match, it was their role in exonerating the black protestors who had been shot at, and then later charged with affray, that Berry values.

“From my point of view the only good thing that came out of this was that as the only non-police white guy to witness the people running away who were shot in the back, I was able to testify when they were charged with affray and it came to court. I was called to give evidence and as a white in those days in South Africa my word was taken as gospel. I was believed over the police. The police said initially that they’d only fired one burst, that the crowd had been aggressive – and certainly two minutes before the crowd had not been aggressive. Some of the pictures show the cops reloading and this proved that they had been shooting a lot longer than they alleged because of the time it took to shoot a magazine.”

"From my point of view the only good thing that came out of this was that as the only non-police white guy to witness the people running away who were shot in the back, I was able to testify when they were charged with affray and it came to court."

- Ian Berry

Berry continued to document apartheid and the racial politics of South Africa for years to come. In the immediate aftermath, “surprisingly there were no repercussions as far as I was concerned. I think the truth was that the South Africans were more concerned with the written word,” he says, although years later, like many other members of the press, he was banned from the country with no reason given – a ruling that was overturned when Mandela came to power.

Despite the Sharpeville massacre feeling seismic in its brutality, “we all thought at that moment that it would cause a change in the political situation in South Africa,” said Berry – “it was really ten years before anything changed.”

Today, in present-day South Africa, March 21, is celebrated as a public holiday in honor of human rights and to commemorate the Sharpeville massacre.