Jérôme Sessini: Afghanistan, September 2021

The Taliban seized Afghanistan’s capital Kabul on August 15th, 2021, following continued victories across Afghanistan. In September 2021 Jérôme Sessini travelled between Kabul, Pol-e Alam and Bamyam, taking photographs and speaking with people along the way.

In September 2021 Jérôme Sessini travelled to Kabul, arriving at the Afghanistan border by car through Uzbekistan. He crossed the border accompanied by Sara Daniel, senior international reporter at L’Obs, and headed to the capital. “The trip was originally planned for August 15th,” he recalls. “That was the day that the Taliban took Kabul. I was literally on a plane when the connecting flight was cancelled. I spent the next three weeks working out how to get to the country now there were no direct flights.”

Jérôme has visited Afghanistan many times over the last 20 years, sometimes embedded with French or American troops. This time he travelled independently and moved freely, and with surprising ease around the country. “I was stressed,” he says. More than 50 journalists have lost their lives in the country since 1994. “I had a lot of questions. I didn’t know if we were going to be welcomed, or if journalists and photographers were going to be safe. In the past, the Taliban’s opposition to the west and its people had been a constant concern. We just didn’t know what was going to happen.”

"“I had a lot of questions. I didn’t know if we were going to be welcomed, or if journalists and photographers were going to be safe. In the past, the Taliban’s opposition to the west and its people had been a constant concern. We just didn’t know what was going to happen.”"

- Jérôme Sessini

What Jérôme encountered was a moment of inertia. The coalition forces had abruptly left in a chaotic evacuation as the Taliban swiftly, and easily, took control of the country. “The Taliban seemed surprised with the speed that they had retaken power. There was a sense that no-one really knew what was going to happen next: there was a lot of tension.” Over the course of a week Jérôme travelled between Kabul, Pol-e Alam and Bamyam, taking photographs and speaking with people along the way. His photos show the Taliban troops, school girls, people in Kabul selling their possessions to fund an exit from the country, and, returning to a subject he has documented in the country before, heroin addicts.

“The Taliban I encountered this time was different to those I met before. They are younger, they are more educated. Some of them went to university in London or Pakistan. Some of them are very good looking and photogenic and they knew how to be nice to the press, I was extremely careful that what I was doing couldn’t be, in some way, interpreted as PR,” he explains. “It made me feel uncomfortable.” This apparent ease was in marked contrast to others that he encountered. “When we spoke to the teachers at the school, we could sense we weren’t being told the full story. They weren’t sure what was going to happen, as nothing had happened; no decisions had been made.” This sense of anticipation played out at every location that Sessini visited. Afghanistan was waiting.

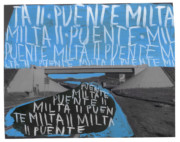

Things have changed, however, for the county’s heroin addicts. “Heroin addicts have been gathering under this bridge in Kabul for years. The people I have met there have a very high level of addiction, they take heroin just to function rather than to have fun and get high,” Jérôme recalls. “The Taliban cleared them out a few weeks after my visit and sent them to a detox center.” Their treatment was an indicator of how quickly things might change once the Taliban organised itself. Afghanistan produces most of the world’s opium supply, generating a huge amount of money. “During the Soviet occupation [from 1979-1989], farmers were encouraged to grow poppies, then when the coalition forces arrived – they were paid to destroy the fields where they grew,” says Jérôme. “There is a huge heroin problem in Afghanistan that is rarely spoken about. Whereas, before, an NGO would help addicts and prescribe methadone and the like, under the Taliban, addicts are sent to hospital and there is no treatment or help. Withdrawal from heroin without substitutes is very harsh and painful.”

Sessini, on this trip, sensed a different feeling in the people of Kabul. “In the cities I felt that some people had lost hope. There is a young generation, primarily in urban locations, that for the past 20 years, have believed that society would change. Before, when there was war, and the support of foreign nations, there was a feeling that change was possible,” he explains. “This time, when I spoke to people, there was a feeling of despair – of fear and desperation. When I returned from Afghanistan, I had many messages asking me to help people get out.”