The Making of Satellites

Jonas Bendiksen reflects on the first major body of work he made, which explored the fates of scattered former Soviet republics

Thinking back on the series of events, and “ill-advised” actions he undertook as a photographer in his 20s, Jonas Bendiksen says one of the driving forces of his landmark project, Satellites, was luck. Happening to be in a specific place, at a specific time, is what led the photographer to make some of the series’ most unique and most memorable images. Yet, through all of his reflections on the project, it’s clear that a keen sense of observation, determination in the execution of an idea, and a certain streak of recklessness were all part of the mix.

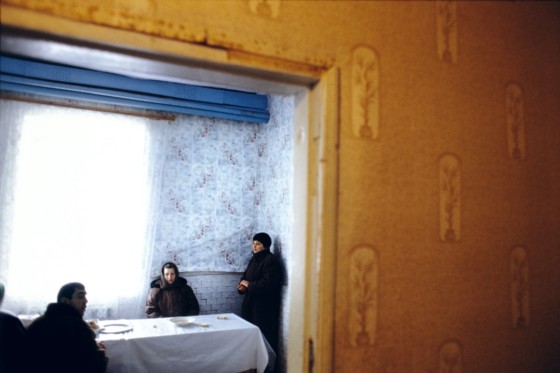

During the collapse of the Soviet Union, economic, political and ethnic disparities gave birth to a series of lesser known unrecognized republics, national aspirations, and legacies. Crafted from a series of Bendiksen’s photoessays made from 1999 to 2005, Satellites documented these places in transition. Six regions undergoing great social shifts formed the six chapters of the book: the “non-existent” state of Transdniester; the beach resort of Abkhazia; the contested region of Nagorno-Karabakh; the Fergana Valley, lying across Uzbekistan, Kyrgyztan and Tajikstan; the spaceship crash zones of the Altai Territory; and the Jewish Autonomous Region of Birobidzhan. Through this collection of vignettes, little-seen in the West at the time, Bendiksen provided an insight into how daily life was lived in liminal places, documenting communities that were experienced the breakdown of Soviet communism in varying ways.

We asked Bendiksen to reflect on the significance of that period and body of work, 15 years after the book was published. He speaks to us about how he recognized the seed of a great idea, tells the story of how he travelled in pursuit of the story, and reflects on how that work took shape in physical forms.

Hear more from Bendiksen on how to build a photographic project in his online course, Jonas Bendiksen: Curiosity in Practice — find more information about it here.

Explore nine works from Satellites available as Fine Prints, part of Jonas Bendiksen’s collection, here, as well as a Magnum Editions 8×10″ print in limited number here.

Satellites was your first book and exhibition. How does it feel knowing that this book is now 15 years old?

On a personal level it is a bit shocking. Time goes by so quickly. My gut feeling is that my whole career has lasted about 10 years. It’s weird to think that I’ve been doing this now for well over 20 years. All the experiences from the Satellites period still feel like recent events to me. I suppose it is because the Satellites years of my life were so formative that I still very much am shaped by it.

Can you talk a bit about how you became interested in Russia, and in turn the former Soviet republics? How did you recognise a promise in your original idea and how did that feel?

First of all, I didn’t start out as a 20-year old thinking I would make a project such as Satellites. At that time I was just pursuing whatever fascinated me, and was trying to figure out who I was as a photographer. Satellites wasn’t conceived until way into the work, when I discovered that all these stories I was trying to tell were pieces of a larger puzzle. The Satellites project found me, more than me finding it, if you like.

The start of it all was that I had this immense curiosity about Russia and the former USSR. This sprung out of my own family history. While I was born in Norway, my mom was a New York Jew: her parents families emigrated from the shtetls of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia to the US just before World War I. So the family I knew growing up was my family in Norway and my family in the USA.

I was 12-13 years old when the Iron Curtain started collapsing, and at that moment our family suddenly got word from family members who were still living in the Soviet Union, a part of the family we had known nothing about. The working hypothesis in the family had been that whatever parts of the family that stayed behind had perished in the holocaust. So this was a huge event in my family. It was a time of great uncertainty and chaos, and what was happening with the Soviet branch became daily dinner table conversation. For me, as a 13 year old who was starting to see the world with grownup eyes for the very first time, this was very eye-opening and made a big impression on me. It was as if my own little family I was part of, in a small town in little Norway, suddenly was thrown into the very endgame of the whole Cold War.

So, as soon as I was ready to start travelling myself, I had this almost irresistible draw towards Russia and the former USSR. My first inspiration was to go to Birobidzan, in the far east, because it was a story that encompassed a lot of the elements from my family history – a place that Stalin himself chose to be the Russian Jews’ “promised land”. It had bits of Soviet history, Eastern European Jewish history, post-cold war history and an uncertain future. Before I went there, I tried to find articles about the place, but had a real hard time finding any good ones. That’s when I realized it was probably a great story to try my hands at, as, if nobody had done this story, it would have big value editorially as well as personally.

In Curiosity in Practice you talk about embarking on Satellites as ‘jumping off a cliff’. what advice do you give to photographers who are looking for confidence to pursue their project?

This is a difficult one, because everyone has a different engine. I remember being also really frightened and insecure at times when I was starting my first projects too – very few are immune to that. I’m not even sure it would be a positive thing to not have any fright, it’s probably healthy. But yes, it did feel like I was jumping off a cliff – I had a certain budget, I was blowing it all on this one journey, and I was going alone to live in a country that I didn’t know at all, and didn’t even speak the language. All I had to go on was this hunch that a story about Birobidzhan, the Jewish Autonomous Region in Russia’s far east, was a good story that hadn’t been done dozens of times.

One thing that gives me confidence when I’m embarking on a new project, is to have quite clearly articulated for myself what the idea I have is, and why it’s something that anyone should care about. I tend to write this down as a ‘pitch’, even if I don’t have any editors or grant institutions to send it into – because the one that it’s most important to convince is myself. If I’ve clearly articulated why I believe in an idea, it’s easier to remind myself why I’m there, once the doubts and insecurities start creeping in.

You had worked as staff at Magnum for a period prior to this. What photographers, Magnum and otherwise, were you inspired by during the time you were making the images for Satellites?

I was an intern at the Magnum London office for one year. It was the lowest position in the hierarchy. I was paid 250 pounds and a metro card per month. But it was really my education in photography: getting to know the archive, spying on all the other staff to understand how they worked, how they dealt with clients, and not the least, seeing all the photographers come and go, and try to study how they worked. At that time, I was seeing photographic heroes like Josef Koudelka coming and going in the building. I even met Cartier Bresson as a 19-year-old, just before I went off on this first trip. I was both inspired and probably also totally star-struck.

Inspiration-wise, I remember just a month or so before I left Magnum and went to Russia, Lise Sarfati had just been admitted into Magnum as a nominee. I was there when the team of staff got the first set of slide dupes of her images and were poring over them to get to know her work. Everyone was blown away by her photographs from Russia, the work that later became her book Acta Est. That was a huge inspiration: her quiet, dark, sophisticated way of looking at things, all in this stark color. I must have taken some of that with me.

In your course, you reflect on your first ever publication — of your Birobidzhan images in The Sunday Times. It helped you to realise that photography could be a profession. What did you enjoy about pitching your stories versus later making your own book?

It’s important to understand – at that time in my career my bread and butter was pitching stories I was interested in to various publications, and getting assignment money to go do that story. That is how most of the chapters of Satellites were made: I pitched some story about, say, Transdniester to a magazine, and got to go there on their ticket – then I would make sure I put in enough time to do my own personal work while I was there. It was after I had been doing this in lots of places that I realized that I was actually working on a book. I was repeating the same stories of unrecognized republics all along the southern border of the Soviet Unions: all these various forms of enclaves, and half-baked territories. Without the editorial modus operandi, I would never have made the book, so these two ways of working were very much intertwined.

Can you talk about the process of expanding the images into the physical forms of book and exhibition?

This was a first for me, and a big challenge. The fewer amount of images you are boiling it down to, the harder it gets. Satellites is quite sparse, just 55 images or so. The images have no captions. The information is all condensed into a narrative text spread that prefaces each chapter. With the book, I was trying to get away from the overtly journalistic or pedagogical – and rather – to try to create a visual poem for each place, in as distilled a form as I could. The book has a lot of ambiguity in it because of that, and that was very different from the various editorial pieces from each territory that came out along the way.

Being kicked out of Russia and ending up exploring the satellite regions was an unplanned turn of events. How much would you attribute your landmark first project to serendipity? What’s the place of circumstance and luck in photography?

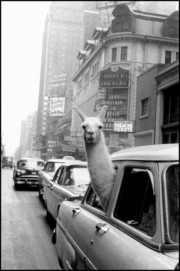

When I look back, it is almost scary to consider the amount of luck. What were the chances of that happening, of those elements lining up? Not only that I was tossed out of Russia, but along the way, I did so many ill-advised things. It’s a long story, but for instance, there’s the example of how I got to finally meet the space rocket crash metal dealers in Kazakhstan. After weeks of trying to get in touch with anyone remotely connected to them, I drove a rusty rented LADA car alone way into this region, a desert-like steppe, trying to get as close as I could to what I had suspected would be a rocket crash site. With the help of some rocket experts, I had analyzed the likely launch trajectories, and had a spot marked on a map in the middle of nowhere.

The car obviously broke down on the way there. Its engine had choked up with sand and dust. I was standing there alone, trying to calculate how I could walk back to the nearest village, probably over a day’s march away, in blistering desert heat. I had some supermarket jugs of water with me. To be honest, it was a terrible idea, and I had no business going there so badly prepared.

But, just as I was starting to prepare my escape from this hairy situation, I saw a column of dust in the distance – and, soon enough, three or four huge trucks were coming my way, Mad Max-style. It turned out that they were the scrap metal dealers I had spent weeks looking for, and they had no other choice than to let me hitch a ride. We drove off, and I got to hang out with them as they chased their crashing space rockets.

This stuff just cannot be planned.

Throughout the stories in the project, your camera is attuned to the unusual, the under-documented, the bizarre – in a highly-connected world, how do we try and resist a preset mold for photography?

That is exactly the question I am asking myself all the time. Much of photography follows templates, pre-fab styles for this or that genre. It worries me. I think it makes us go blind. What does it take to excite me photographically? What will make people actually stop and look, instead of just think, “seen it all before”?

My instinct is to not worry so much about photographic language, but rather to chase after the stories and questions that fascinate me. Then, photography becomes a method of exploring those questions or issues. We might run out of new ways to photograph things, but we won’t run out of interesting ideas, or human beings who find themselves in thought-provoking or challenging situations. It’s those scenarios that get me up in the morning and inspire me to make new work.

How might you approach this project differently if you had to do it again?

I think any attempt at making Satellites again would surely fail. What is unique about this project in the arc of my career is that it was made when I was figuring out how to do things for the very first time. I didn’t have the ballast of experience – that is why it feels so raw, so unfiltered. Now, I know too well how to attack each of those situations. It would probably result in other good images, but it would surely lose the unpolished rawness that makes Satellites so dear to me.

Having said that, I am looking to make a new edition of the book. It has been sold out for years, and I get messages all the time from people who ask for a reprint. As part of that process, I would want to go through all the raw material from scratch… perhaps tweak a few things. I know of at least one image I regret not having put in back then.

You can hear more from Bendiksen and learn to build your own photographic projects in 18 video lessons online now. Find out more about Jonas Bendiksen: Curiosity in Practice here.