Myanmar’s Rocky Path to Democracy

30 years on from the 8/8/88 uprising, Burmese-born photographer Chris Steele-Perkins reflects on the 23 years he has spent documenting the country

The modern history of Myanmar can be carved in two parts; before and after the uprising of August 8, 1988. It began as a small student-protest but quickly grew into a nationwide general strike led by thousands of civilians against a longstanding dictatorship. Despite the bloody military crackdown that followed, spirits weren’t dampened and Aung San Suu Kyi emerged from the rubble two years later, welcomed as the country’s democratic savoir.

Thirty years on, hopes have dimmed and the Nobel winning Suu Kyi has had a dramatic fall from grace. Burmese-born photographer Chris Steele-Perkins has been documenting the country for 23 years and during that time witnessed it unfurling from a military dictatorship into a more open and accountable state. When he visited in 2013, he felt positive about its future. “Now I’m not so optimistic,” he says.

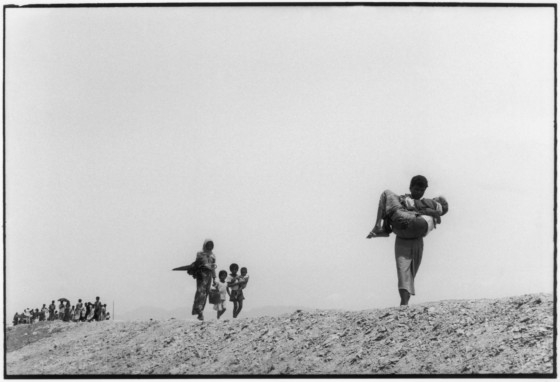

Steele-Perkins’ first experience of the country as an adult was from the border of Bangladesh. In graphic black and white, he portrayed the atrocities of the 1992 Rohingya crisis, the result of long-simmering ethnic tensions that have scarred the country for decades. He chose not to document the most recent Rohingya crisis — “I just felt like I’d be taking the same pictures I’d already taken years ago”— but believes the long-term question for Burma is how to resolve the ingrained ethnic inequalities.

“It’s the classic postcolonial issue of who controls the power and the wealth in the different ethnic groups that are bundled together,” he says. “This is the big problem and it seems to be writ large with the Rohingya situation because of the extremity of it but there are wars going on as we speak in other ethnic minority areas.”

During his visits in the late 90’s, Steele-Perkins said Myanmar was comparable to Nazi Germany. “There was a feeling of constant uneasiness. I was aware of government agents who hung around and just looked at people – they were almost everywhere, looking, looking,” he said. “And you got a sense of paranoia. The behaviour was controlled so closely by the government that families would be expected to tell on other families if they’d been doing the wrong sort of things.”

As a result, taking pictures was not a straightforward affair. “It was a difficult time because the military were in very considerable power and the locals didn’t want to be seen talking to foreigners because they would get in trouble,” says Steele-Perkins. “I have family there and the first time I went back I didn’t contact them because they were concerned about what might follow.”

When Steele-Perkins visited in 2013, the country felt markedly different. There was a gradual loosening of state control which followed the 2011 elections, when Myanmar’s first civilian government in decades took office. “Burma began to interact with the outside world and tourists came – and they realised this was actually something they rather liked,” he says. New hotels were being built, areas that were once restricted opened up and tourism was encouraged, meaning he could embark on a more expansive photographic exploration of the country as a whole.

“It became an awful lot easier to travel around,” he says. “I don’t think there were any areas I went into except military controlled ones where people treated you negatively because you were a photographer. Although bizarre things would happen still, like you’d be in a town and the police would jump up out of nowhere and drag you to a police station and very politely tell you you had to leave at 5pm because there was no way you could stay there overnight. You would get incidents like that still but they were surreal rather than dangerous.”

This political shift is evident in the focus of the post-2011 work. From rice planters toiling on the land in Hmawbi, to young boys kicking a football on a waste ground in Bago, to an elderly man enjoying an early breakfast, these small scenes—all captured through a questioning lens—accumulate to create a full and vivid picture of Burmese culture. “I realised in the 20 years or so I’ve built up more of a question of: ‘Is this country like the one I was born in?’” says Steele-Perkins. “But without any sentimental homecoming ideas.”

The work has never been charged with political intent but Steele-Perkins admits one “knocks up against it now and again”. Thirty years on from the revolution that was so hinged upon the the democratic hope of Suu Kyi as a leader, there has arguably never been less international support for her. “That was a big disappointment,” he says. “The sacrifice of her many years under house arrest seems to have been a sort of ego trip to get herself where she felt she belonged: at the ruling Junta’s top table. It’s a pity, but we’re not back to exactly the same spot. I suppose it has carved an openness which may bring its own kind of fruitfulness.”

Steele-Perkins plans to return to Myanmar in 2019. “I want to travel to the north as much as I can and maybe look at trying to put a book together,” he says. “But anything I put together would be as incoherent a narrative as my journeys there have been. Something has emerged but it’s not easily quantifiable.”