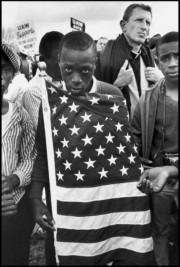

In Pictures: Tracing the Activism of Stokely Carmichael

On the 20th anniversary of his death, we look back at the life of the Black Power organizer, from student protestor, to one of the most prominent voices of the Civil Rights Movement

Magnum Photographers

From influential student activist, to a celebrity of the civil rights movement, to his eventual withdrawal from the United States and involvement with African Nationalism; photographs from the Magnum archive show the political trajectory of Stokely Carmichael, a key figure within the Black Power movement.

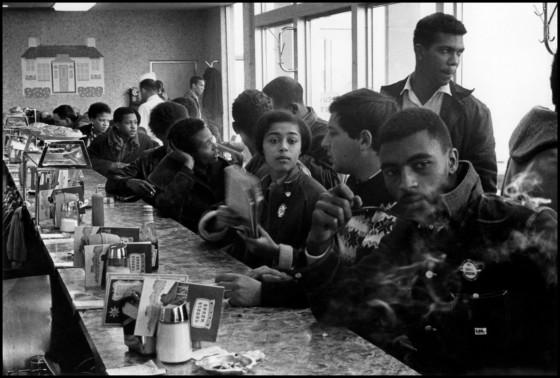

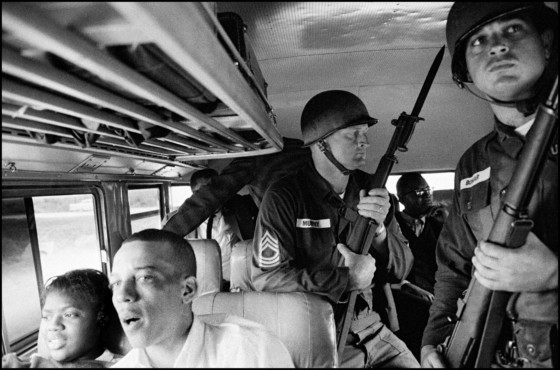

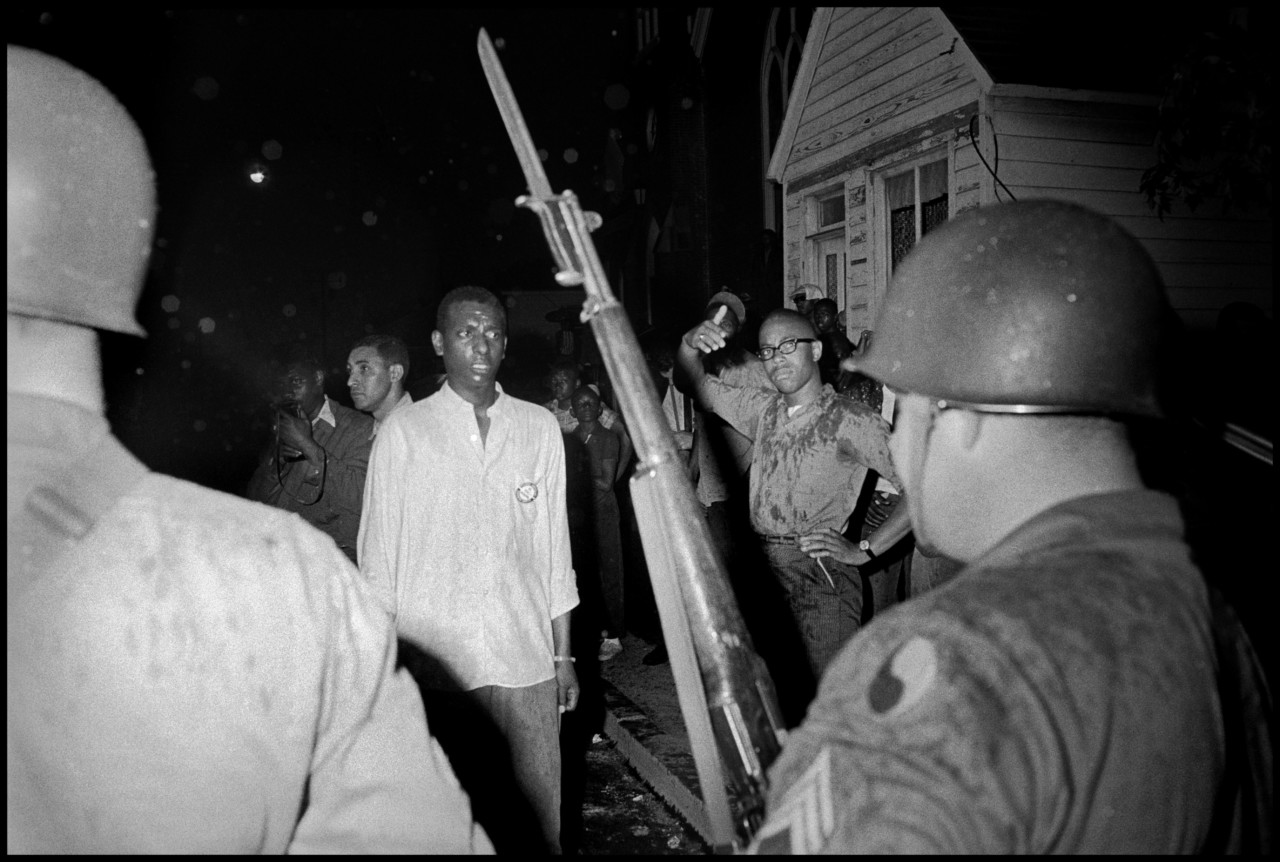

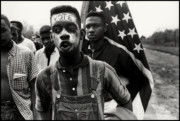

Danny Lyon was staff photographer for the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), the grass-roots activist group responsible for the ‘sit-ins’ and Freedom Rides in segregated restaurants and public transport in the Southern United States. Initially a volunteer, Stokely Carmichael was the group’s chairman in 1966-1967. When asked about Carmichael’s legacy, Lyon said: the “SNCC, a largely black organization, was integrated with blacks, whites, and Jews risking themselves and at times dying in the Movement. Stokely’s accession to the Chairmanship, replacing John Lewis, would eventually lead to the expulsion of the whites from SNCC. […] The divisions caused by SNCC no longer being an integrated group would eventually lead to its weakening effectiveness and eventual collapse.”

A divisive figure to this day, Carmichael’s later work represented a turning point in the civil rights movement from non-violence to militancy. Commenting on Martin Luther King’s approach in The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975, he said “In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none.” Criticized by both opponents and fellow activists in the civil rights movement for his separatist rhetoric and outspoken, celebrity leadership style, his appearances in both mainstream media and activist circuits led to some members of the SNCC nicknaming him “Stokely Starmichael”.

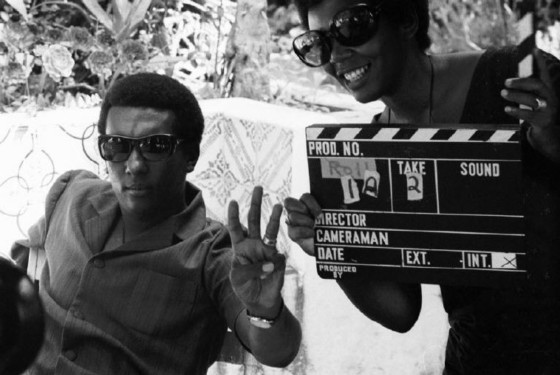

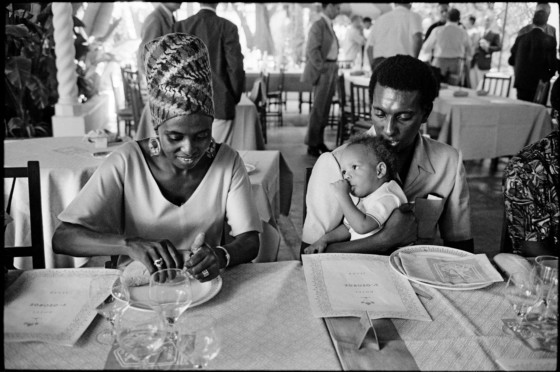

His ease in front of the camera can be seen in casual and intimate moments captured by Magnum photographers. In 1969, Guy Le Querrec and Bruno Barbey photographed Carmichael at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers: the former in candid shots with his son Bokar and his wife of five years, the singer Miriam Makeba; the latter, in several spontaneous and dynamic portraits. Reflecting on the impressions of the man, Bruno Barbey recalled his charisma – “Carmichael had an incredible big smile”.

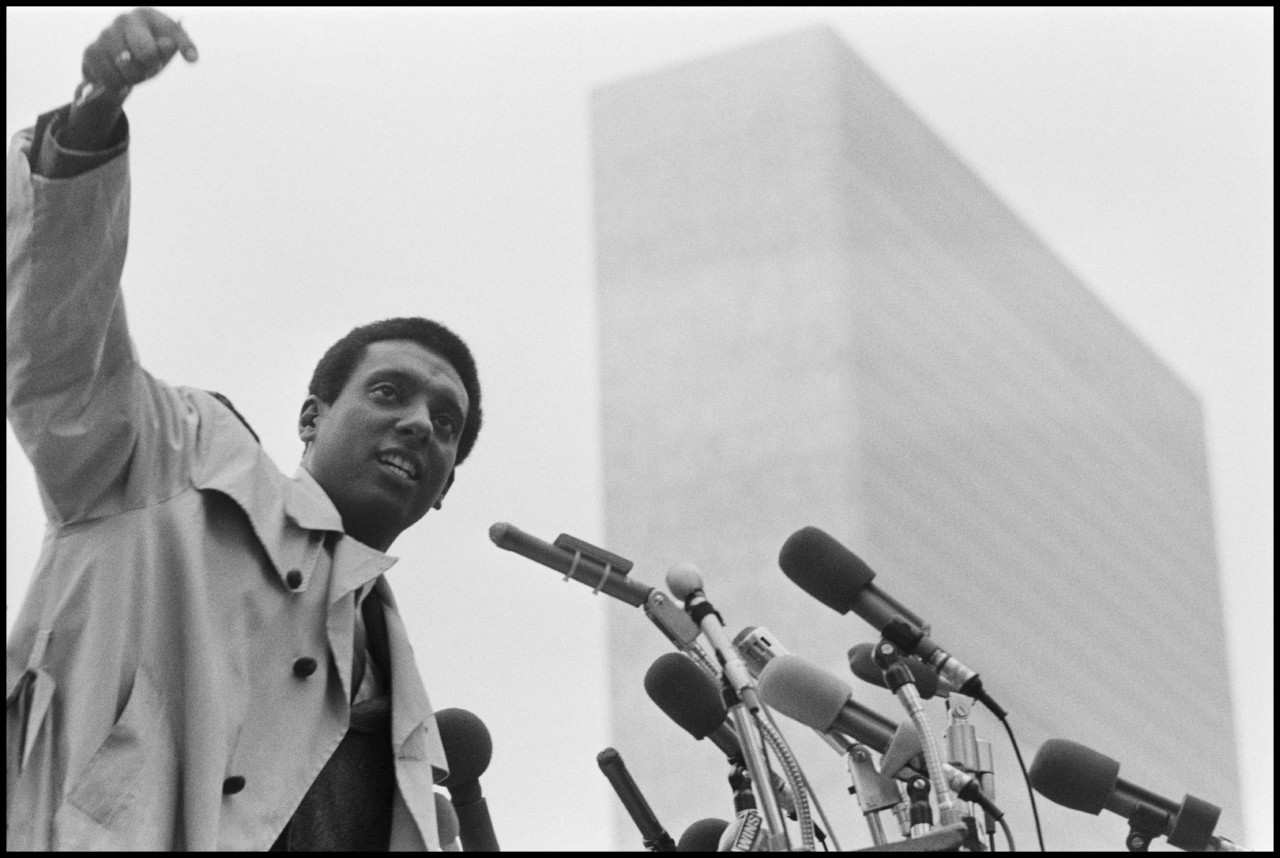

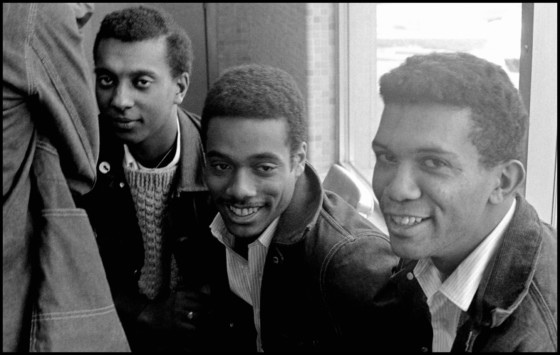

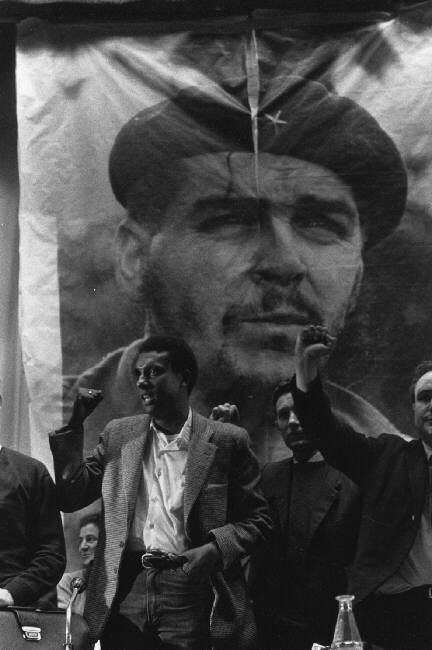

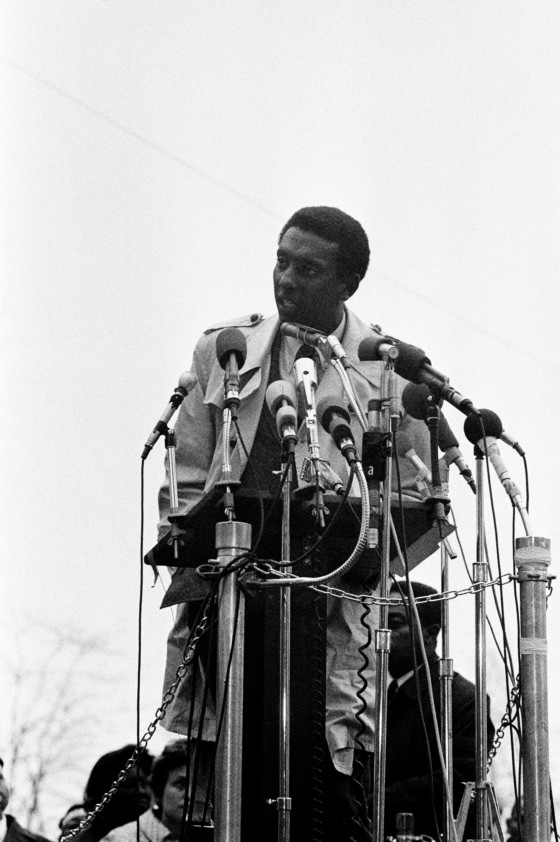

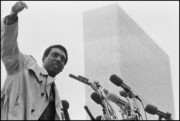

Hiroji Kubota and Burt Glinn captured Carmichael’s speech at the NYC Peace March in protest of the Vietnam War in 1967, where he shared the stage with Martin Luther King. The same year, Raymond Depardon photographed Carmichael at the anti-Vietnam War meeting in Paris. Bruce Davidson shot Carmichael after another speech in 1966, just as he had become chairman of the SNCC, with friend and writer Claude Brown. When asked about the role of photography in the struggle for civil rights, Davidson said: “The movement was about black power and it was important for the camera to capture the pain and the oppression during that time.”

The violence student activists faced from authorities was a constant during their nonviolent protests of the early 1960s. Danny Lyon’s 1993 memoir Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement reflected on a demonstration in Cambridge, Maryland in 1964: ‘Stokely Carmichael, then twenty-two years old, was seated at the very front of the line of demonstrators, and the gas was sprayed directly into his face. He must have suffered terribly. That night most of the staff went to visit him at the hospital.” Lyon’s photographs were used in promotional and fundraising materials for the SNCC, and served the role of bringing media attention to racism that the students faced. Writing about Lyon’s Civil Rights photography, Julian Bond said: the “SNCC’s idea of photography was functional … Danny Lyon took this function and made art”.

"The movement was about black power and it was important for the camera to capture the pain and the oppression during that time."

- Bruce Davidson

After a year in the position of Honorary Prime Minister of the Black Panther Party, Carmichael changed his name to Kwame Ture in 1969, after the Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah and the Guinean president Ahmed Sékou Touré. Increasingly radicalized over his activist years, he became known for his socialist, Pan-Africanist speeches and essays.