Spain’s Ghosts

The Spain chapter is the latest in Alex Majoli's ongoing Titanic project, which explores the ideology and identity of Europe

THE MANAGER- “I can’t see. Let’s have a little light, please!”

– Luigi Pirandello, Six Characters in Search of an Author

Colorful protests, flags, screaming headlines — this was how most of the world saw the political struggle that Spain faced in the fall of 2017, the biggest constitutional crisis the country has faced since the failure of an attempted coup in 1981. But the series of photos that Alex Majoli took in Spain capture it in stark black and white; his photographic style uses artificial light to cast shadows, sculpting the bodies and faces of the “actors.” The effect of his use of flash is highly theatrical, turning the cityscape into a two-dimensional set — which, combined with the overall dark and dramatic tones of the photos, present scenes that blend fact and fiction. “I wanted to shine my flash on society and see how the photographed subjects would react. Over the years I came to realize we often reenact something that we have already seen,” he explains, citing as an influence the 1967 work of Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle. In this book, the French Marxist theorist presented his concept that the spectacle “is not a collection of images, but rather it is a social relation among people, mediated by images.”

This influence can be seen in Majoli’s images, which go beyond news imagery by conveying a mysterious sense of timelessness, echoing that same suspension of time that occurs on stage. The bullfighter José Padilla stands defiant, statuesque, an eye-patch covering the socket of the eye he lost in the bullring; an old man kneels down arranging his gear. His portrait seems to belong to the 1940s, right after the Spanish Civil War, when the victorious General Franco imposed a repressive regime, and along with it, a single idea of Spain. All difference — regional, linguistic, religious, sexual — was banned, and symbols and traditions that had been apolitical became heavily charged. Bullfighting was not inherently the domain of the right or the left, and many intellectuals, poets and writers who opposed Franco were ardent fans of these ritualized battles between men and bulls.

But in Spain today, many see bullfights as a cruel tradition, epitomizing some tyrannical and brutal national characteristic. The ban on bullfights in Catalonia, passed in 2010, came to represent a deeper struggle against Spain. Although the first region to approve such a ban was the Canary Islands and there are several cities and villages where the fiesta nacional has disappeared, in Catalonia the ban has been tainted with nationalistic politics. (The Constitutional Court overturned the regional ban in 2016, saying that the Catalan parliament did not have the authority to ban “one more expression of a cultural nature that forms part of the common cultural heritage.” Despite the overturning of the ban, no bullfights have taken place in the region since.)

More than forty years after the death of Franco, in 1975, and three decades after Spain joined the EU, this past fall the ghost of Francoism was alive once again —buzzing with a nightmarish, caricaturesque energy. Democratic, European Spain was presented by supporters of Catalan independence as a fraud, a deceit, a mere extension of its autocratic past. And among the vast majority of Spaniards and about half of Catalonians who do not want an independent Catalonia are also a small number of forgotten and marginal supporters of the late dictator, portrayed in these pictures saluting in Madrid with a nostalgic fervor.

The separatist movement had gained new life in recent years as Spain struggled with the fallout of the global economic crisis. Catalonia accounts for about a fifth of Spain’s economic output — though it has one of the largest public debts of any Spanish region, at more than 72 billion euros — and many Catalans believe their taxes contribute more to the country than they get in return. Support for independence also surged in 2010 after the Spanish Constitutional Court decided to strike out parts of the 2006 Catalan statute of autonomy, which was approved at referendum and would have given the region greater independence.

"I wanted to shine my flash on society and see how the photographed subjects would react."

- Alex Majoli

This long-running standoff between Catalonia and the central government in Madrid escalated rapidly last year. At the beginning of September, with a slim majority of 70 seats out of 135, the Catalan regional parliament approved a call for an October referendum on independence. Regardless of the turnout, it was decided that if a majority voted in favor of seceding from Spain, a unilateral declaration of independence would follow in 48 hours. Neither the Spanish Constitution nor the Catalan legislation allow for such a move.

The independentist cause was championed by Carles Puigdemont, the president of the regional government and leader of PdeCat (Catalan Democratic Party), the conservative nationalist party that in 2015 campaigned for independence with the leftist nationalist party Esquerra Republicana. The far-left group CUP, with 10 seats, completed the defiant political trio: These three parties were determined to break away from Spain and stay in the European Union, despite the fact that Catalonia already enjoyed among the highest degrees of self governance of any region in Europe, directly controlling education, health services and their own police force.

This fall, the central government and the anti-separatist parties in Catalonia insisted that no such illegal referendum would be held at all — but it only seemed to strengthen the resolve of many Catalans to cast their vote, and thus reclaim their so-called “right to decide.” The attempts of Spanish police to confiscate some ballot boxes during violent raids led to crowded protests and ultimately failed. Two million of Catalonia’s 5.5 million citizens turned out, undeterred by the efforts of the riot police to scuttle the vote. The press flocked to Barcelona to document the political drama, and Majoli captured them too — an essential player in this drama.

Over the following weeks, independence was withheld, proclaimed and then suspended. Amid the political upheaval, more than 3,000 businesses moved their legal headquarters out of Catalonia, Spain’s third most prosperous region. Puigdemont and several members of his regional cabinet escaped to Brussels, and public prosecutors charged the leaders of two Catalan associations behind the protests with sedition and rebellion. The judges put both under provisional detention, along with the leader of Esquerra Republicana, Oriol Junqueras. The pro-independence camp denounced the incarceration of these leaders, seeing them as political prisoners.

"The drama is in us: we are the drama, and we are impatient to represent it"

- Luigi Pirandello

In the stage directions of Six Characters in Search of An Author, Pirandello writes about a “dream lightness” in which those searching characters enter the stage, and appear “almost suspended,” though, he adds, “this does not detract from the essential reality of their forms and expressions.” It is precisely such a dreamlike atmosphere that Majoli captures, exposing the myths that underpin reality. The woman behind bars, photographed by Majoli, was part of a civil performance where citizens rotated entering a fake prison to denounce the arrest of the Catalan leaders. The performance within the drama, citizens playing out as characters searching for an author, or eager to be part of the play, reclaiming a role in a historical time. As the character of the Father says in Pirandello’s work, “the drama is in us: we are the drama, and we are impatient to represent it: our inner passion drives us to this.”

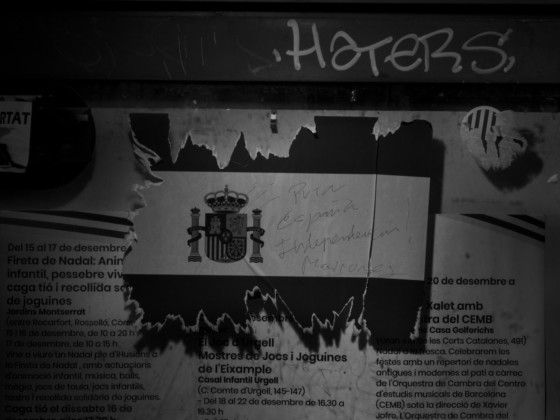

In early November, the Spanish government, supported by the main opposition party, took an unprecedented step and applied Article 155 of the Constitution, suspending Catalonia’s autonomy and allowing the central authorities to take over the regional government. It was presented as a temporary measure that allowed for the organization of a regional election on December 21. The protest against the implementation of Article 155, portrayed by Majoli, shows a group of men building a human tower, the traditional castell, a Catalan tradition that dates back to the 18th century. The performance aspect of reality is heightened once again. Another image features a sticker on a streetlight demanding their freedom — an urban metaphor of the crossroads and, perhaps, of the need to come to a halt?

"This does not detract from the essential reality of their forms and expression"

- Luigi Pirandello

The photographer cites Pirandello’s play as the theoretical foundation upon which he’s built his ongoing Titanic project, which explores the ideology and identity of Europe. His reflections on the crises affecting Europe have resulted in a solid body of work shot in 10 countries over the past four years. The rise of the populist far-right, the arrival of refugees from war-torn countries, and the reception these people have had in Europe constitute the three main axes of Majoli’s exploration of the current challenges facing the EU. After a long career shooting in conflict zones all over the world, Majoli turned his camera to the place where he grew up, highlighting the growing cracks in the European project. “We are so scared, everybody is confused and confronting a deep identity crisis,” he says.

Catalans turned out for the December election in high numbers, with over 80% of the electorate casting a ballot. The results showed that the majority of Catalan voters were against seceding from Spain, but the pro-independence parties succeeded in holding onto a majority of seats in the Catalan parliament. Former president Carles Puigdemont, since fleeing to Belgium in October at risk of potential charges of rebellion, sedition and misuse of public funds, now heads a new group called Junts per Catalunya, the second-most popular party in the elections. His former ally Junqueras, from Esquerra Republicana, remains in prison; he has pledged to support Puigdemont as president of the Catalan government. Carles Riera, leader of the far-left CUP, who raised his fist as he voted, lost six seats. In the end, December’s vote showed that there is no unified Catalan stance against Spain; no clear majority to break away. Catalans and Spaniards as a whole are confronting one another and some uncomfortable truths.

Again, Pirandello’s words ring true: “You who act your own part become the puppet of yourself. Do you understand?”

Andrea Aguilar has been a contributing writer to the Spanish daily El Pais since 2003, and a contributing editor to Ideas, its supplement, since 2013. Her work has also been featured in The Paris Review and El Malpensante, amongst other publications.