Television and the Presidential Debate

On the 60th anniversary of Nixon v Kennedy — the first ever televised leadership debate — we explore the impact of the medium on modern politics

The first debate between Joe Biden and Donald Trump takes place on Tuesday September 29, 2020. If the 2016 election demonstrated anything, it is that debate performance will not necessarily swing an election. However, political legend suggests that it once did. The 1960 election was the closest race since 1916, culminating in the election of John F Kennedy. His rival, Richard Nixon, had had the upper hand for most of the campaign but for decades afterwards critics and pundits would suggest that he did not lose the election in November, but 6 weeks before, on September 26, 1960, when the first ever televised presidential debates aired to 70 million Americans.

“Without TV,” said Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan, “Nixon had it made.” He was more experienced, having served two terms as Eisenhower’s vice president. He was a Cold Warrior who could go toe-to-toe with world leaders, as he had with Khrushchev in the “Kitchen Debate”. However, Nixon was not as aware as Kennedy of television’s power to influence public opinion, and not as prepared.

“Kennedy took it seriously,” recalled the producer Don Hewitt in a 1997 interview. Kennedy had taken Hewitt up on the offer of a pre-production meeting, whereas Nixon had declined. “Kennedy knew it was going to be important. He rested that afternoon. Nixon made a speech to the Carpenters’ Union that day in Chicago…Arrived at the studio, banged his knee when he got out of the car, was in pain, looked green, sallow, needed a shave.”

Everything from his sweaty sheen, to his five o’clock shadow was blamed for Nixon’s unfortunate appearance on screen next to a tanned, powdered and laid-back Senator Kennedy. It seems superficial but reactions at the time seemed to emphasize how important the candidates’ appearance on television had been. Lyndon Johnson listened to the debate on the radio and felt Nixon had bested his running mate. However, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr, Nixon’s VP pick, had watched on television and was reported to have said, “That son-of-a-bitch just lost us the election.”

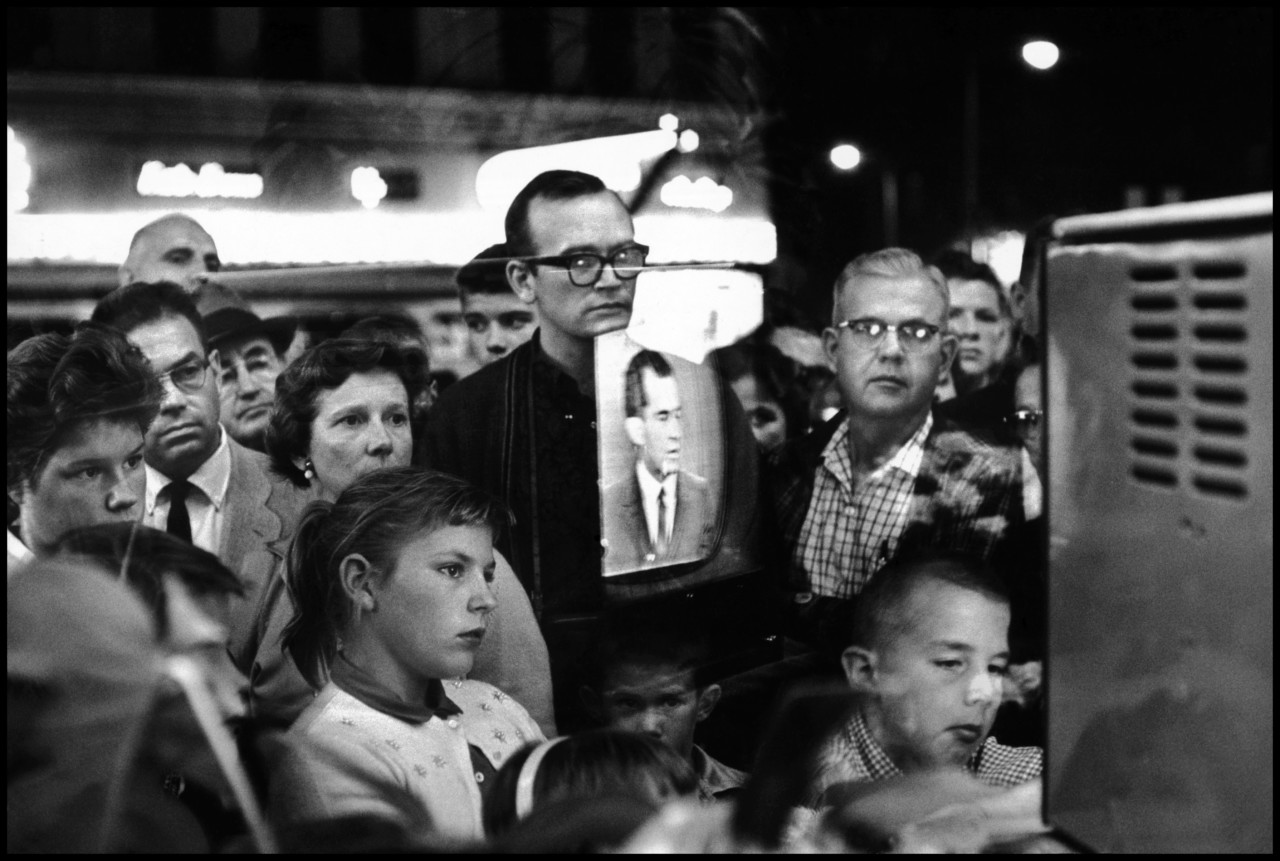

Cornell Capa captured viewers watching the debates, of which there would be four. In one photo, a crowd surrounds a monitor, looking at the screen with intense interest. Nixon’s image is reflected in the glass. In another photo, the last debate plays on a television inside a sparsely populated bar in New York. Kennedy and Nixon are just about visible, glowing gently blue. Despite the difference in the amount of people in these two photos, what they share is the sense of the debate as an “event”, something of deep curiosity and even entertainment.

Bars would continue to serve as settings for the communal watching of the debates. Alex Webb visited Club Deja Vu in Youngstown, Ohio in 2008 and photographed patrons watching the second Obama/McCain debate. In one photo, a barman with his back to the camera looks up at the screen, head cocked in absorption or incredulity, we do not know. In another, a woman stands arms folded, her head tilted upwards, her expression indecipherable.

The expressions of viewers were also Bruce Gilden’s focus when he photographed people at The Village Pour House in New York City in 2016. “I didn’t watch too much of the debate because I was looking at faces,” he tells us over the phone. “There were very limited opportunities to photograph because it was very crowded.” The crowdedness of the sports bar contrasts with earlier photographs but compounds the sense of the debate as a spectator event. Gilden’s impression of the attendees also hints at McLuhan remarks in 1970 that television is a “mythic form”. It can make politicians more than politicians, at least while they are on screen. “If I remember correctly, it was totally pro-Hillary […] Looking at these pictures, I can imagine a 16-year-old girl looking at a Hollywood movie and wishing she was on the screen. […] In a couple of the pictures, I watched them looking at the screen quite dreamily…”

Interestingly, there are far more of Gilden’s photos where people look either slightly tense or disinterested. There are no extremes of emotion. With hindsight we know that Clinton would be considered the winner of all 6 debates, but some of the facial expressions Gilden captures seem to unwittingly forecast how little that would matter.

This was in sharp contrast to the 1960 debates. The fact that there were no televised debates for the next three elections would lend a mythologizing power to those first debates and the idea that a candidate’s appearance and performance on television could directly bring about their downfall. In the opening chapters of The Selling of the President, for which journalist Joe McGinniss followed the 1968 Nixon campaign, he reports on how Nixon and his team surrounded themselves with experts on the medium who knew how to use television “as a weapon.”

For McLuhan, what made Kennedy a “TV President”, as he would dub him in a 1969 Playboy interview, was that he was “the first prominent American politician to ever understand [its] dynamics […] Kennedy had a compatible coolness and indifference to power…” His nonchalance left enough space for the viewers to project onto him, to make him more than a politician. In 1976, McLuhan called the televised debate between Ford and Carter, “the most stupid arrangement of any debate in the history of debating.” McLuhan felt Ford and Carter were too stiff, too scripted, too performative, not understanding that television was a “cool” medium that responded to understatement. The blurring of politics and entertainment that televising political debates had brought had also brought the blurring of politics and celebrity. It is perhaps no surprise then, that according to Nielsen, the October 28, 1980 debate between Carter and Reagan held the record for the highest audience figures for 36 years, with 80.6 million viewers.

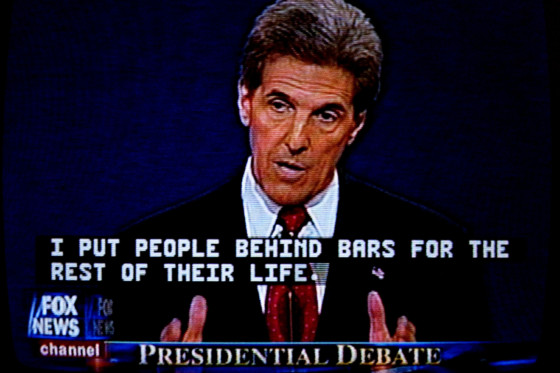

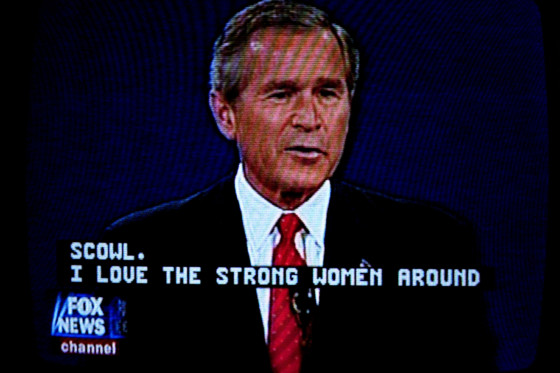

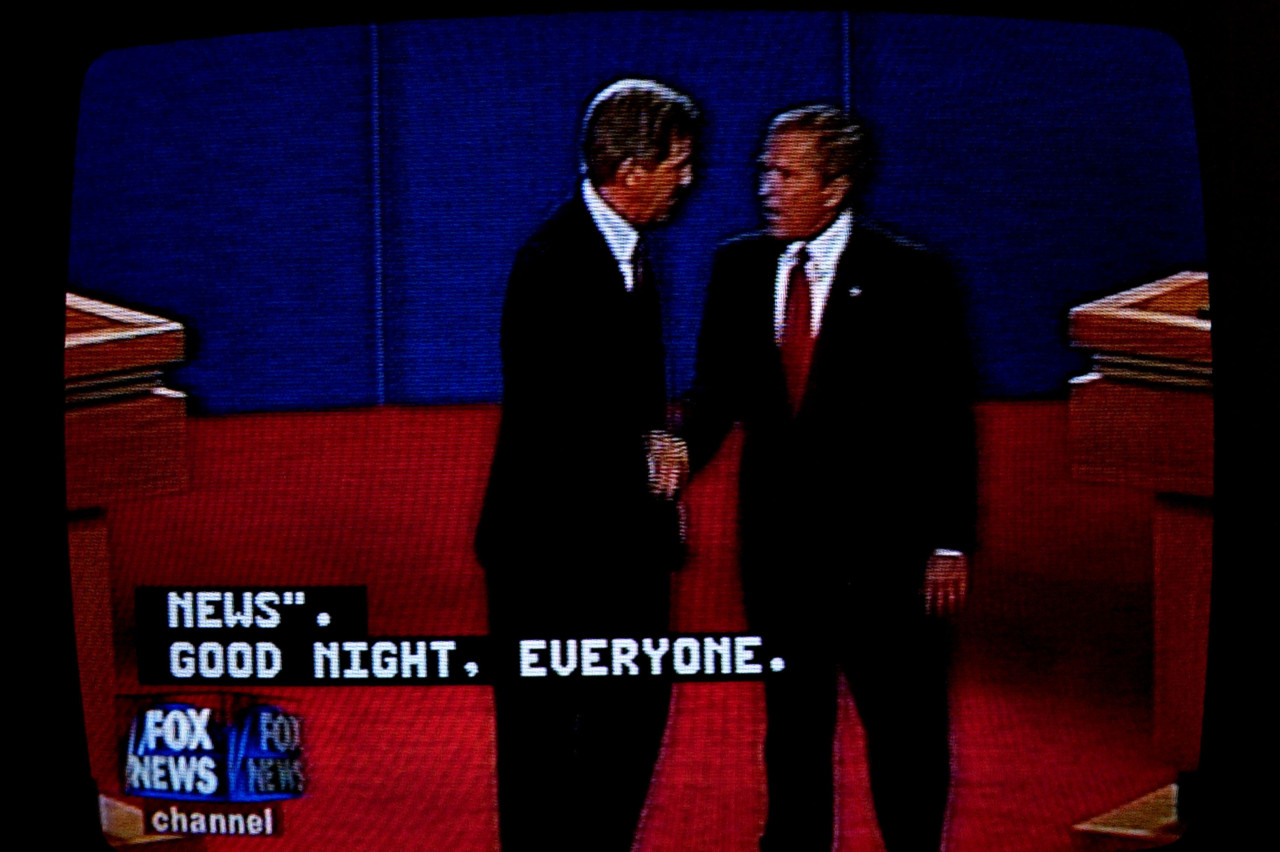

Television was still king in the early 2000s (the power of the internet in politics would not really come to the fore until 2008) and while audiences had long been accustomed to the medium itself, the debates still seemed to harbor a visual peculiarity which is expressed in Thomas Dworzak’s photographs of the 2004 debates. There are no spectators, the focus is the screen and what is on it. The Bush vs Kerry images are striking in their “tv-ness”: the black frame as a result of the small aspect ratio, the fuzzy lines across the candidates’ faces, the large subtitles which make strange poems that highlight the inherent awkwardness and drama of political speech. Kennedy and Nixon pop up in these debates too. Dworzak’s image makes them an unsettling hybrid creature, their mouths and eyes merging.

Dworzak’s 2016 photos provide an even more surreal effect thanks to the strange “art direction” of the debates themselves. Clinton and Trump, himself a TV-obsessed and TV-savvy candidate, stood in front of a backdrop of extracts of the Constitution. Several of Dworzak’s photos capture a blur of words and faces, distorted and overlapping. For Dworzak, television is the perfect medium for this spectacle, at least visually speaking. He tells us over the phone, of the upcoming debates, “I think probably the right way to take pictures of Trump and Biden during the debate should be on TV. […] This is the right way of doing it. The virtual world. I think it should stay there.” Comparing the effect of his images over time, Dworzak laments what is lost with technical innovation. “The TV sets are too good! There used to be a thing you could do to drop the shutter speed [in order to merge multiple frames], but it doesn’t work anymore. The weirdest thing about TV [now, with its higher frame rates] is that it makes everything crisp.”

It remains to be seen how the pandemic will affect the visual presentation of the 2020 debates and how the audience will receive two candidates about whom much has already been made of age, appearance and performance on camera. On the influence of the debates Denise-Marie Orbey and John Wihbey wrote in 2016, “To the extent that the debates are important in terms of persuasion, the format may slightly favor the challenger, about whom the public knows less.” This time around Trump is not someone most people know only as a celebrity, as a man from the TV.

Airing the televised presidential debates every election for the past forty years has stripped them of their novelty and the fanfare around them shows how thoroughly they have been absorbed into the circus of the election season. But these photographs taken over the decades make the visual language of the debates strange again. We see American politics has a color scheme (red and blue). Things that were once novel, such as the split screen, reveal themselves to us anew, making still photographs diptychs. The blur of hands and pursing of lips highlight awkward gestures and strange speech. Photographs like these emphasize the surreal nature of politics on television, seeming to visually represent the distorting effect they have on viewers, an effect that cannot be gleaned from those faces as they watch the screen.