The Quality of Mercy: COVID-19 in the UK

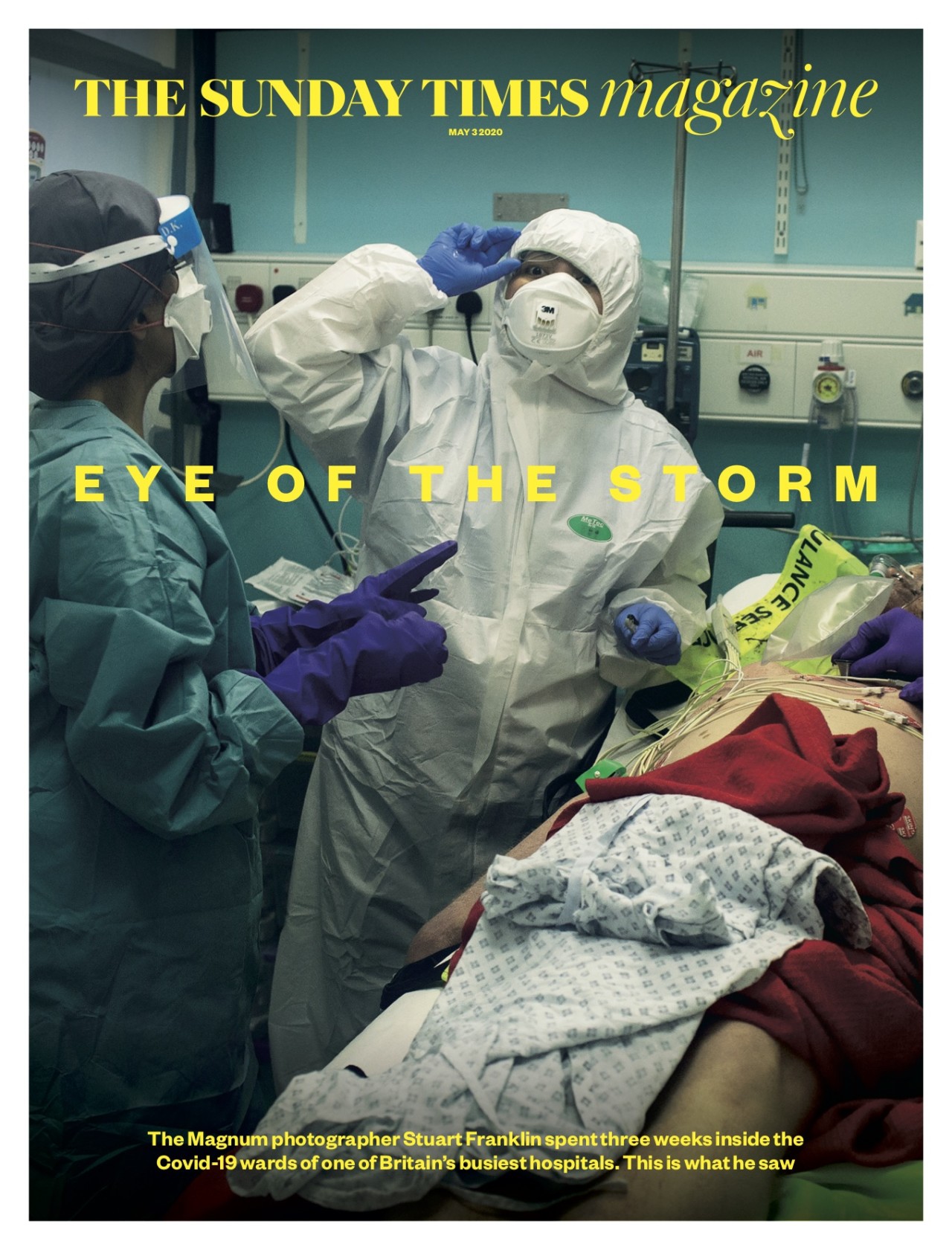

Stuart Franklin reports on the experiences of medical staff at London's West Middlesex University Hospital, examining how the UK government "endangered many who might have been safe"

The quality of mercy is not strained.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

William Shakespeare

Following the publication of my Sunday Times magazine story documenting London’s West Middlesex hospital (West Mid) during the COVID-19 pandemic, I am writing further on the physical and psychological impact of COVID-19 on doctors and nurses faced with saving lives and protecting patients. I want to talk about three doctors and three nurses and their experiences. My wife, Caroline, an A&E consultant at West Mid, made my access to the hospital possible. First, some background.

The quality of mercy, over the period of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK, has not been a singular, unstrained, act of benevolence. Public inquiries will be held, no doubt, but the facts seem clear now that the action that the British government took to protect staff and patients in hospitals and care homes endangered many who might have been safe. Has Britain become, I wondered, what used to be called a Third World country?

In January COVID-19 was officially designated a High Consequence Infectious Disease (HCID). All healthcare workers were advised to wear a gown and an FFP3 respirator mask and visor when dealing with patients. On March 13 the government downgraded its guidance on personal protective equipment (PPE) and told national health staff to wear basic surgical masks in all but the highest risk cases. This was all reported by BBC Panorama who understood that on the same day the government took steps to remove COVID-19 from the lists of HCIDs.

A BBC investigation stated that “the government failed to buy crucial protective equipment to cope with a pandemic.” Brexit steered the government away from procuring with Europe. The quality of mercy and care from health-workers that I met, during the month that I spent in West Mid, was unstinting, selfless and unstrained. The quality of mercy and care offered by the British government and Public Heath England (PHE) remains in question. While the total number of COVID-19 deaths in the UK recently passed the 50,000 mark, the steep rise in COVID deaths between March and April (Office of National Statistics data for England and Wales) from 4379 in March to 27764 in April was catastrophic. Limited testing and quarantining of UK airport arrivals at an early stage, a chronic shortage of ICU beds and the staff to support them, the downgrading of personal protective equipment (PPE) guidance, and disregard for care home staff and patients, have all contributed to the crisis.

According to The Guardian, the number of healthcare workers who have died in the UK due to COVID-19 has reached 200. Most died in April; more than half grouped as BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) including both the Filipino parents (nurses in the same hospital) of a fourteen-year-old girl. Under these statistics lie those many, many doctors, nurses, paramedics, porters, and cleaners who fell ill with COVID-19 and whose lungs may never completely recover.

The report published by Public Health England this week, on June 2, confirmed that BAME groups were more likely to die as a result of COVID-19. The full report can be read here.

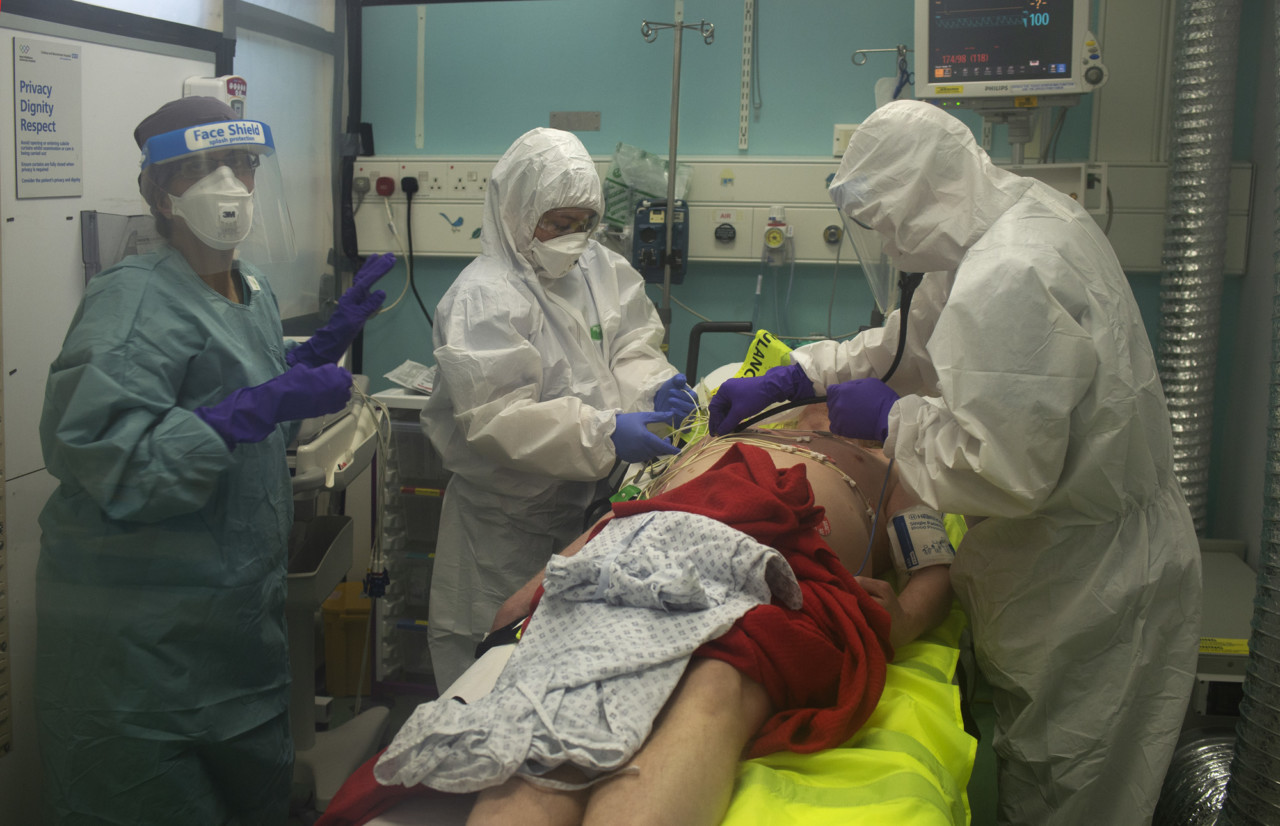

COVID-19 first appeared at West Mid in early March 2020, at the time when Charlotte Scuse, the matron in charge of A&E, was tasked with staffing a Heathrow transit hotel used as a quarantine centre for those arriving from China, Iran and South Korea. In the weeks that followed, as Charlotte and others recall, the downgrading of PPE guidance caused anxiety amongst front line doctors, nurses and ancillary staff. When I first began photographing in the hospital in the last week of March, no-one was wearing protective equipment unless dealing with known COVID-19 cases. Only on April 2 were basic surgical masks supplied for all A&E staff. A local school science lab supplied some visors. It was very basic.

Many of the junior doctors off-shift talked with worried family members. “We are all lying to our parents,” Dr Ece Nur Cinar, from Istanbul, told me on my first day. She was referring to the six or seven junior doctors from, for example, Sri Lanka, Syria, Nigeria and Pakistan – all of whom expressed their concerns about PPE and that, because the British PPE problem was so well known worldwide, they each struggled to persuade those at home that they felt safe at work. Ece told me that she suffered from anxiety and periodic COVID symptoms. At the end of March about a quarter of the doctors and nurses in A&E were off sick with COVID-19, including at least two of the seven consultants. One was Jasmin Cheema, 45, a British-Asian A&E doctor who appeared (wearing green) on the cover of The Sunday Times magazine.

"According to The Guardian, the number of healthcare workers who have died in the UK due to COVID-19 has reached 200. Most died in April; more than half grouped as BAME including both the Filipino parents (nurses in the same hospital) of a fourteen-year-old girl."

-

It was her first day back at work. She tested positive for COVID-19 at the end of March and remained at home sick for two weeks. “There were two days when it took me one and a half hours to come downstairs,” Jasmin recalls. At her lowest point, listless and dogged by breathlessness, severe muscular pain and exhaustion, Jasmin adds, “I remember closing my eyes and thinking, I don’t care if I don’t wake up.” Feeling guilty about not helping her colleagues in the hospital she pushed herself to return to the front line. It was on that first day, April 13, still suffering from tiredness, that I captured her in the cover photograph. Another doctor, Parisa Amiri, 37, a locum registrar from Iran, fell ill at the same time with similar symptoms. I visited Parisa in her north London flat on April 11. She had been in bed for two weeks. She was barely able to reach the door. She was exhausted, breathless, and it was not until April 27 that I saw her back at West Mid. “I thought I was going to die,” she told me of her time with COVID-19.

On April 18 I met Felix Soriano, 51, a much-loved Filipino staff nurse working in West Mid’s A&E department. His 21-year-old daughter Seth brought him to hospital on April 8. He was struggling to breathe and was put on a CPAP oxygen mask in ICU. “That CPAP,” he recalls, “I had to learn how to breathe with the machine. I saw death there, if I made a mistake. I was really, really, really scared.” But Felix prayed and never lost hope. He found succour in the incredible upwelling of support from his wife, Maria, from Seth, and from the nurses and doctors around the hospital who sent hundreds of supportive WhatsApp messages. “They consider me as family. Without their prayers, their advice, their love, I would have lost hope.”

Felix, a British citizen who has worked at West Mid since 2009, went home just three hours after I visited him for a second time and he’s back at work now. He had a message for others in peril: “if I could do it, they could do it too.” While it seems comforting to report that Jasmin, Parisa and Felix are back at work, physical and psychological symptoms persist. Today, at the end of May, Jasmin reports functioning on about 65% capacity in terms of stamina, breathing and fatigue. “I have a lot of anxieties about what state my lungs are in,” she says. A&E doctors and nurses are a tough lot, but, as Jasmin underlines, “it’s seeped under all our skins … I am much more emotional than I used to be.” Whilst the peak of the pandemic in the UK may be past in hospitals, the summit of psychological trauma, for many, is still wrapped in cloud.

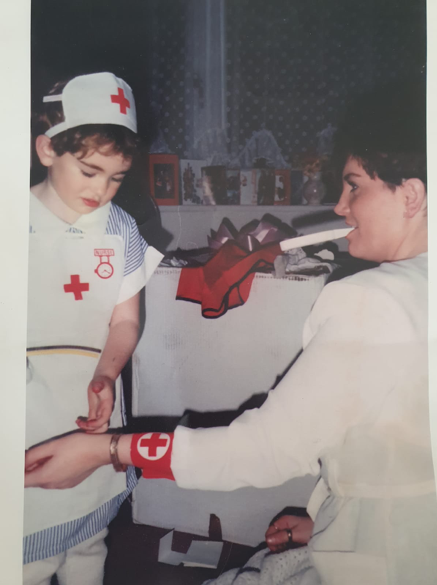

“I have honestly never been more proud to be a nurse,” Jade Thorne, 29, a senior diabetes specialist nurse, told me after spending the most traumatic few weeks of her life tending to COVID-19 patients in two London hospitals. Her last shift at the Nightingale hospital was on May 4. Nursing, for Jade, was always a vocation: “I have never, ever, wanted to do anything else,” she said.

There’s a family photograph of the aspirant nurse, aged four, playing at caring for her mother, Tracey, a hairdresser. The picture was taken in Ensbury Park, a Bournemouth suburb where Jade spent her formative years. Moving to London in 2016 she worked first at Charing Cross hospital before settling in at West Mid. Everything changed on March 27 when Jade answered the call to attend an intensive care orientation day. Akin to wartime expediency nurses were needed to support the expanding intensive care unit (ICU). “I wasn’t scared of coronavirus,” she said, but was apprehensive as to how she might be effective as “a fish out of water” in the ICU.

Her first shift, on April 1, was “horrific”. “I watched someone die on a ventilator … the man was the same age as my Dad.” Jade tried to stay near him, by the window, so that he wouldn’t be alone at the end. It is the nurses’ role to conduct the “last offices”: to wash and prepare the bodies, place them in a shroud and remove any jewellery. When the patient died, she recalls, “I remember removing his wedding ring to give back to his family and it absolutely broke my heart. Tears were running all over my face. I remember telling myself to be strong … I thought how it would feel to receive that ring, but not the patient.” Her experience of losing patients in the ICU has made her reflect on the preciousness “of love and life and family.” She did witness a patient successfully transition off a ventilator on her last shift at the Nightingale hospital at London’s ExCel centre.

The patient was under light sedation. Jade played Gujarati chants from a computer, then shouted out the one Gujarati phrase she knew: “Kem cho? Majama?” (roughly, “How are you, all fine?”). The man opened his eyes. Subsequently, his condition improved and he could be extubated, the result of a team effort, where, during the COVID crisis, nurses have come together. In Jade’s words: “we have been brave and tried to adapt our profession, supporting and teaching each other to get through this … we’d look into each other’s eyes to give each other strength.” Earlier, at West Mid, when a patient awoke while under sedation, he signalled for a pen. On a paper towel he wrote, “please call my wife and tell her I’m OK.” On another day, passing the nurses’ station, Jade took a phone call. It was the son of a patient on CPAP about to be put on a ventilator. “Just tell my Dad that I love him,” the son asked. That was the last family message the patient heard.

I first met Jade a few days after she finished at the Nightingale. “I’ve hit a bit of a wall,” she told me. Off “the treadmill” of long twelve-and-a-half hour shifts she described replaying her time in the ICU. “My heart just feels very heavy now.” Painting by numbers and gardening help to lighten her sorrow. Although many health workers are used to seeing death, Dr Andrew Molodynski, mental health lead for the British Medical Association and a consultant psychiatrist, insisted to BBC news, “We aren’t used to seeing lots of people die when we can’t do anything about it.”

Teresa Uithaler, 27, a nursing sister from Port Elizabeth, South Africa, was drafted into the West Mid ICU from A&E on April 3 where she shared shifts with Jade Thorne. Unable to return to her home in Lewisham (her boyfriend is an asthmatic) Teresa has been lodging in a local hotel, subsisting on room-service hamburgers and beef stew. It’s a boxed-in world at “home” and work. For a week she woke up spontaneously each morning at 4 AM.

4 AM was when her patient for three weeks, Melvin Gwanzura, a 43 year-old teacher, passed away on April 23. “We were never prepared to see young people actually dying of it [COVID] despite trying everything,” Teresa admits. “I would talk to him. I would sing to him. I was really willing for him to be OK. You’ve got so many people who love you, I would tell him,” recalling the worst moments of her nursing career when she witnessed his seizures: “I have never felt so helpless.”