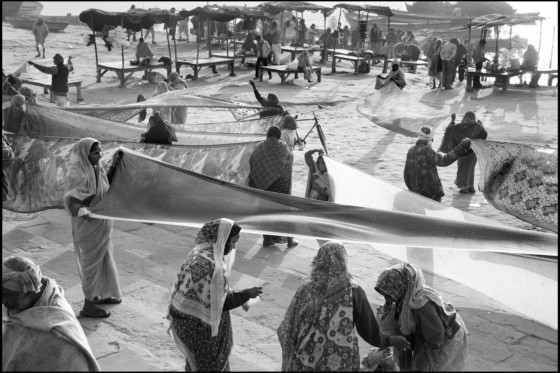

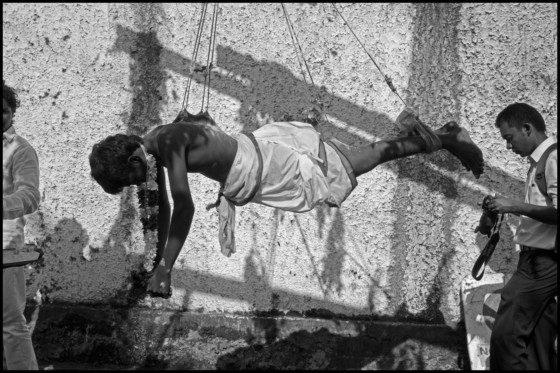

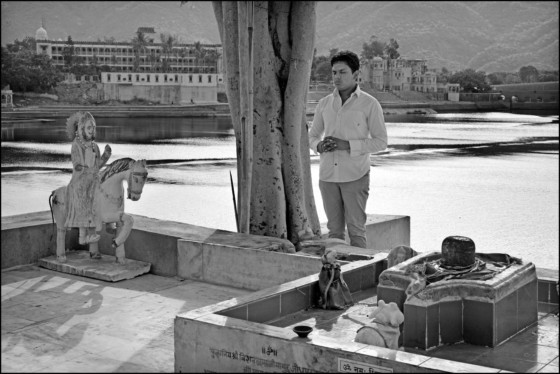

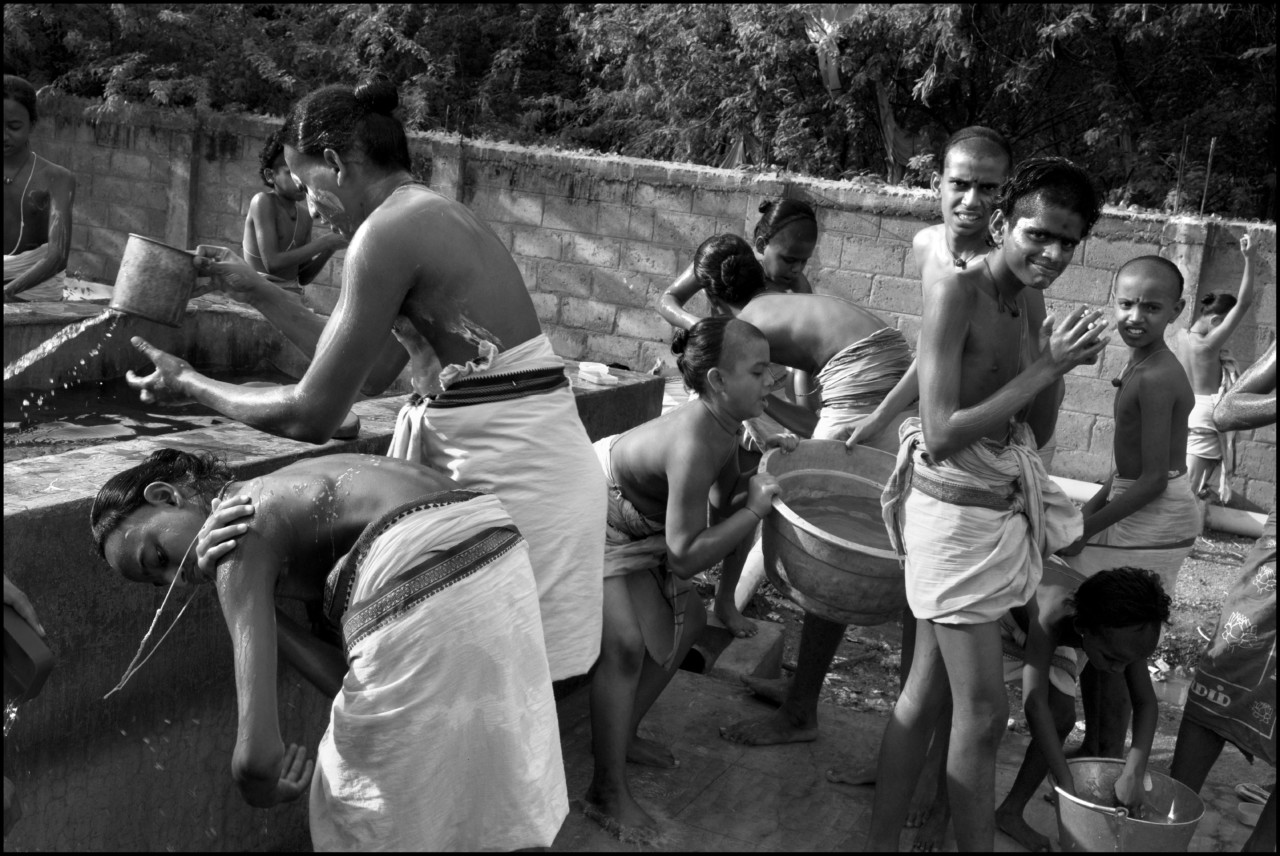

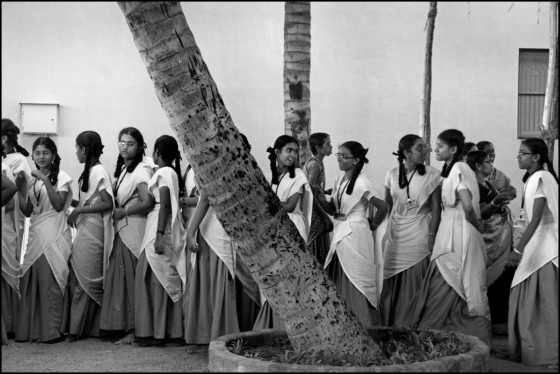

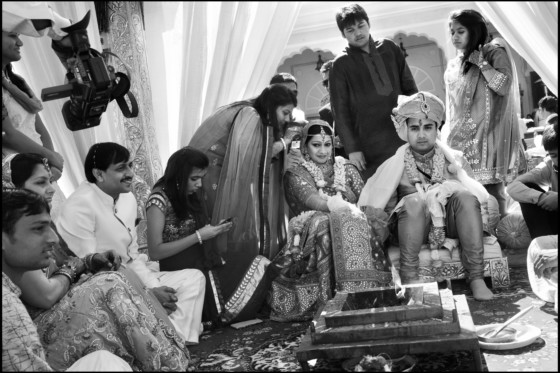

Abbas introduces his book ‘Gods I’ve Seen’, which draws on three years’ worth of travelling across India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bali, photographing the ceremonies and artefacts of religions jostling side by side in the region, including Hinduism, Sikhism and Jainism. The tome is a continuation of Abbas’s study of major world religions, featuring ritualistic elements – wind, water, earth, and fire, magic, and the spiritualism of animals.

I am not the first, nor, I suspect, the last traveller, to have been enthralled by India – and irritated, if not exasperated by the Indians. My reading induced in me a certain feeling of goodwill towards Hinduism, this religion of 330 million gods and goddesses who change name, nature and sex, who marry, divorce and ask for alimony, who are strangely familiar to us in their doubts and weaknesses and so are, all in all, very human gods. These gods do not have the loftiness or the arrogance of the monotheistic gods; like us, they are capable of the best and the worst.

Rituals

In Bikaner, at five o’clock in the morning I wake up with a start to the yelling of a pandit reciting the sacred texts through a loudspeaker at full volume. I am surprised by this blunt intrusion into my room and my sleep, for Hindu temples only rarely employ the human voice. The puja bells at dawn are much more of a nuisance – the gods must be well and truly deaf! At six o’clock, when the muezzin calls the pious to prayer, I understand the reason for this use of technology: the two priests are evidently in vocal competition, each making sure that the other may not monopolize the airwaves. I would no doubt have enjoyed this sacred spar had it been in the afternoon, for one voice proclaims the uniqueness of god, the other praises multitudes. But at dawn, with a long day’s work ahead of me? What to do, other than clear out of this city?

Worship

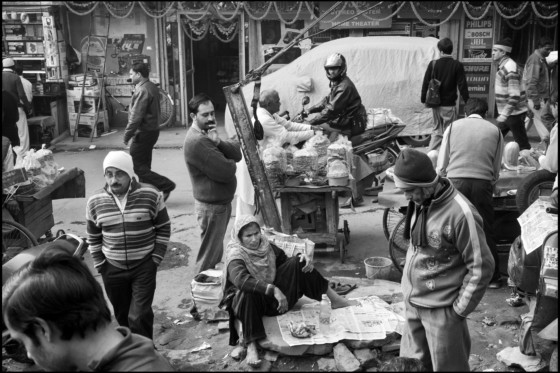

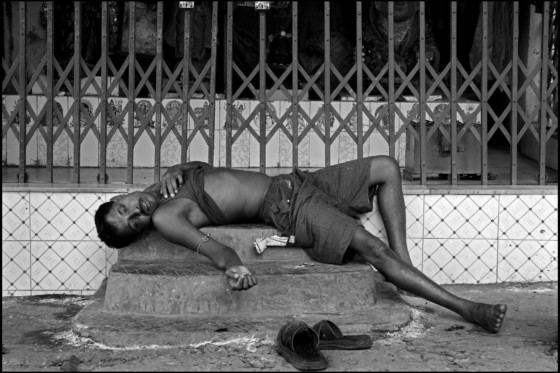

In Kolkata, having worshipped Durga for several days, the Bengalis then drown her in the river Hoogly. Merry processions bring her to the riverside to bid her farewell and throw her into the sacred waters. The same holds true for other divinities: the celebration of Wishwakarma, the divine architect and god of labour, precedes that of Durga, after which comes the festival for Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity. An exercise in wastefulness, repeated every year. I ask a Bengali professor why the authorities do not decree a puja (prayer ritual) for cleanliness, to clean the city of its all-pervasive filth using just a portion of what is spent on statues. “It is because Kolkata is the city of joy, and we must celebrate our gods and goddesses,” she retorts. Obviously.

On The Road

At the Chennai museum, contemplation of a statue of Shiva Nataraja elevates me to the highest spheres of spirituality, as would a painting by Cézanne or a Beethoven symphony. I also discover Shri Devi and Bhu Devi, Vishnu’s two companions, one of whom displays an aristocratic gentleness while the other has the look of a voluptuous country girl. I am amused by my own sensual and spiritual communion with these two goddesses, ever so carnal in their bronze bodies. Who were the great artists who brought them to life? Why have they remained anonymous?

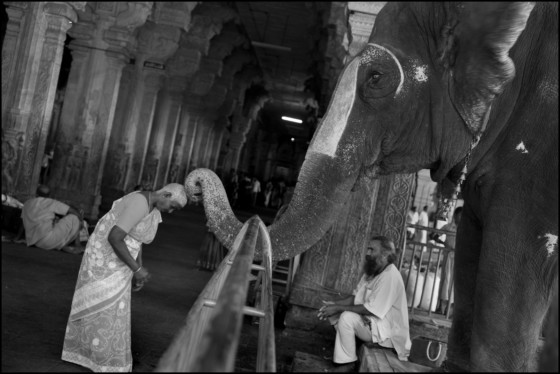

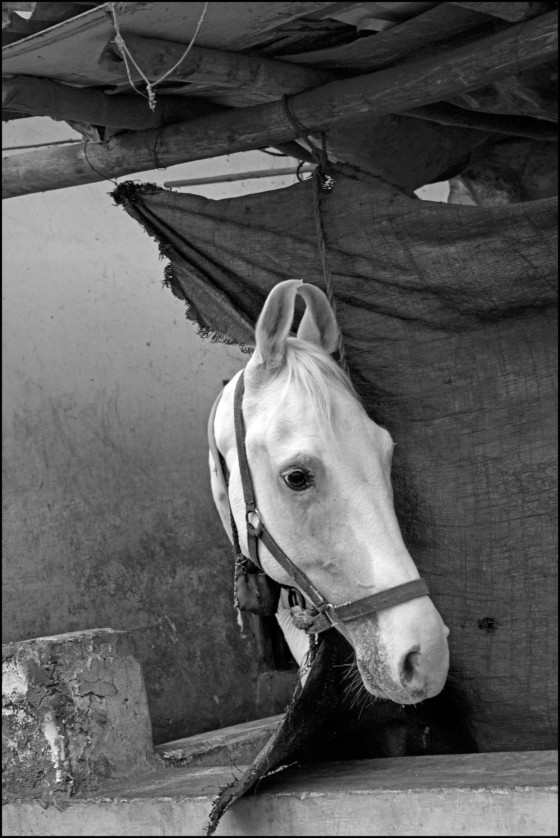

Beasts

As soon as I arrive in the karni Mata temple, a little rat comes to sniff me, probably a scout sent ahead to see if I am rat-compatible. Clearly I am, for immediately afterwards another rat, fat and no doubt holy too, climbs up my leg. I let him know, this fat, sacred rat, that despite having immersed myself in Hinduism for more than two years, it has not made me a rat-lover, and that I see in him neither a god nor the reincarnation of a maharaja, but a simple fat rat, and that I would prefer us to keep our own counsel – me, a bipedal Homo sapiens, and him, a four-legged Rattus norvegicus. I ask him firmly but politely – for we are being observed – to get off my leg. He complies.