Pilgrimage to Uman

As the the annual Jewish convergence on the Ukrainian city begins, two Magnum photographers offer authored perspectives

Magnum Photographers

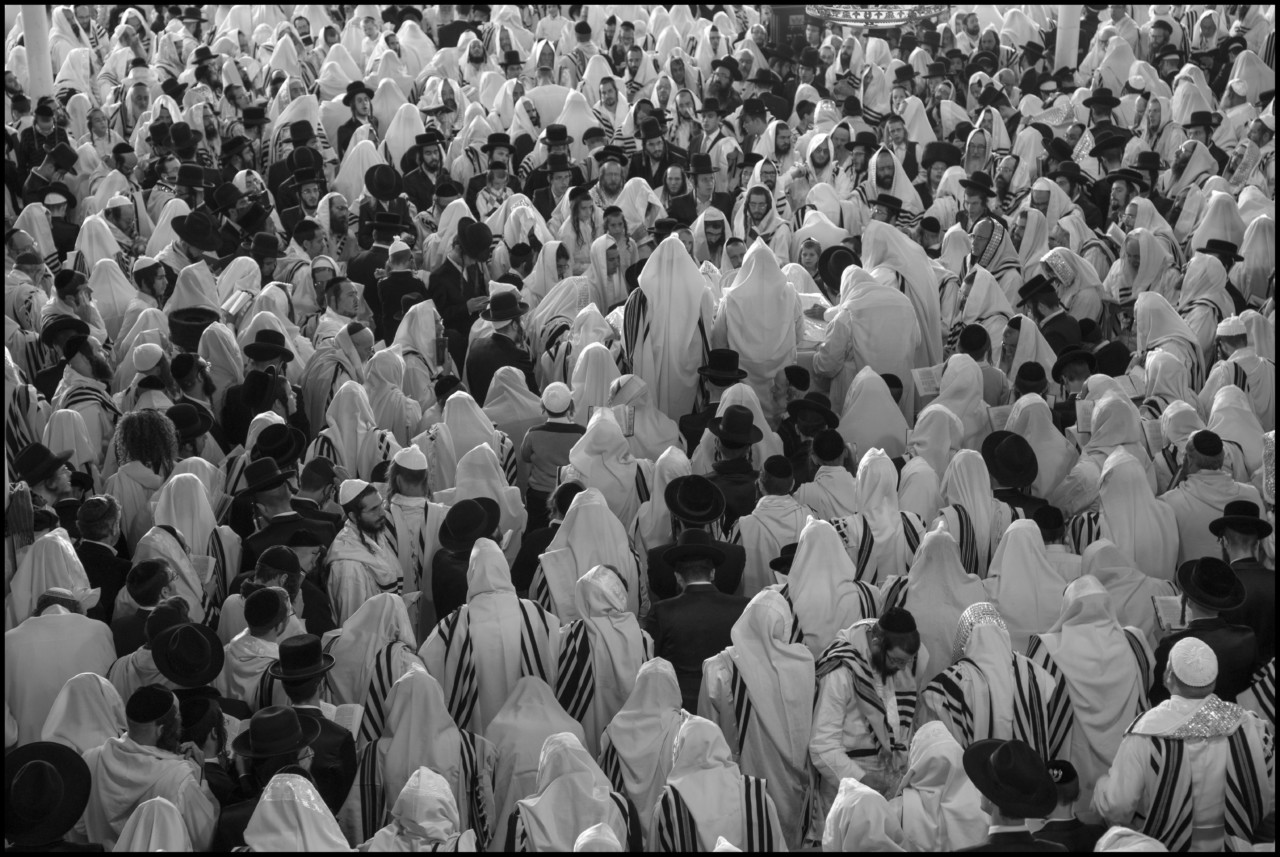

Annually, on the occasion of Rosh Hashanah – the first of the of the Jewish high holy days – tens of thousands of Hasidic Jews, and others, journey from around the world to Uman in central Ukraine. They are making a pilgrimage to the burial site of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, located on the former site of the Jewish cemetery in a rebuilt synagogue.

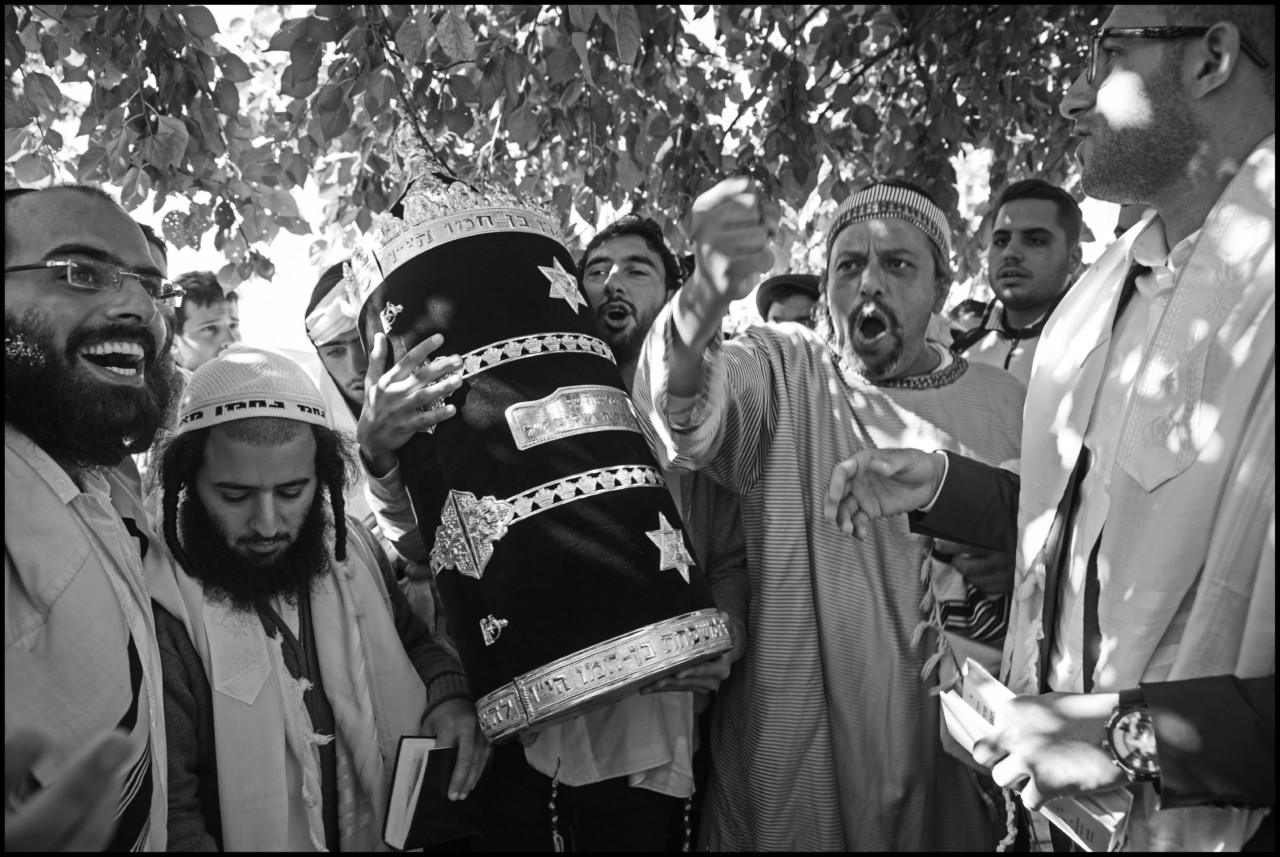

Rebbe Nachman spent the last five months of his life in Uman, and specifically requested to be buried there. As believed by the Breslov Hassidim, before his death he promised to intercede on behalf of anyone who would come to pray on his grave on Rosh Hashanah. The first Rosh Hashanah pilgrimage took place in 1811, organized by Rebbe’s foremost disciple, Nathan of Breslov.

Now, every year, pilgrims flock to the small city of Uman. Having spent much of his esteemed career documenting religious traditions, Abbas has photographed the pilgrimage to Uman. Fellow Magnum photographer Patrick Zachmann, whose interest in the Jewish rite came from a more personal motivation, has also documented it. Here, the pair of Magnum photographers present their “regards croisés” (crossed gazes).

Abbas

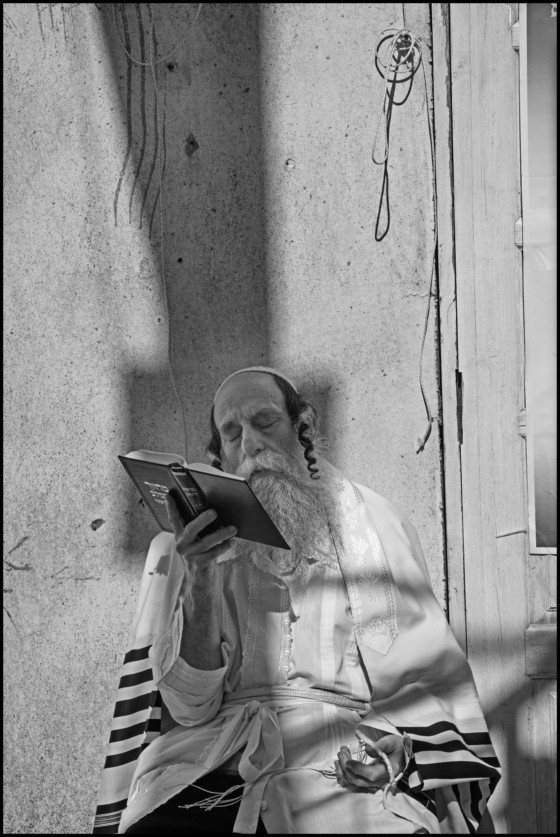

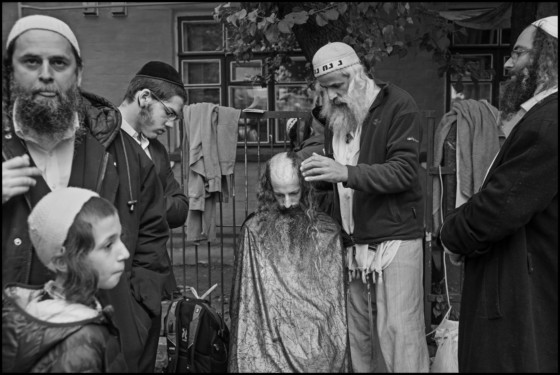

“Jewish pilgrims look as serious and as dedicated as the Muslims going to Mecca or the Christians to Lourdes; some engage in a painful dialogue with God, the weight of their sins appears as a shadow on their face. However, in contrast with other monotheistic communities, all of a sudden these pilgrims start to sing, scream, dance, bursting, for which I am thankful for as it allowed me to capture strong images.

Work, and therefore photographic practice, is forbidden to Jews duringRosh Hashanah, and sometimes, I get scolded when I shoot. When that happens, I argue the following: ‘I am not Jewish but I am kosher’.

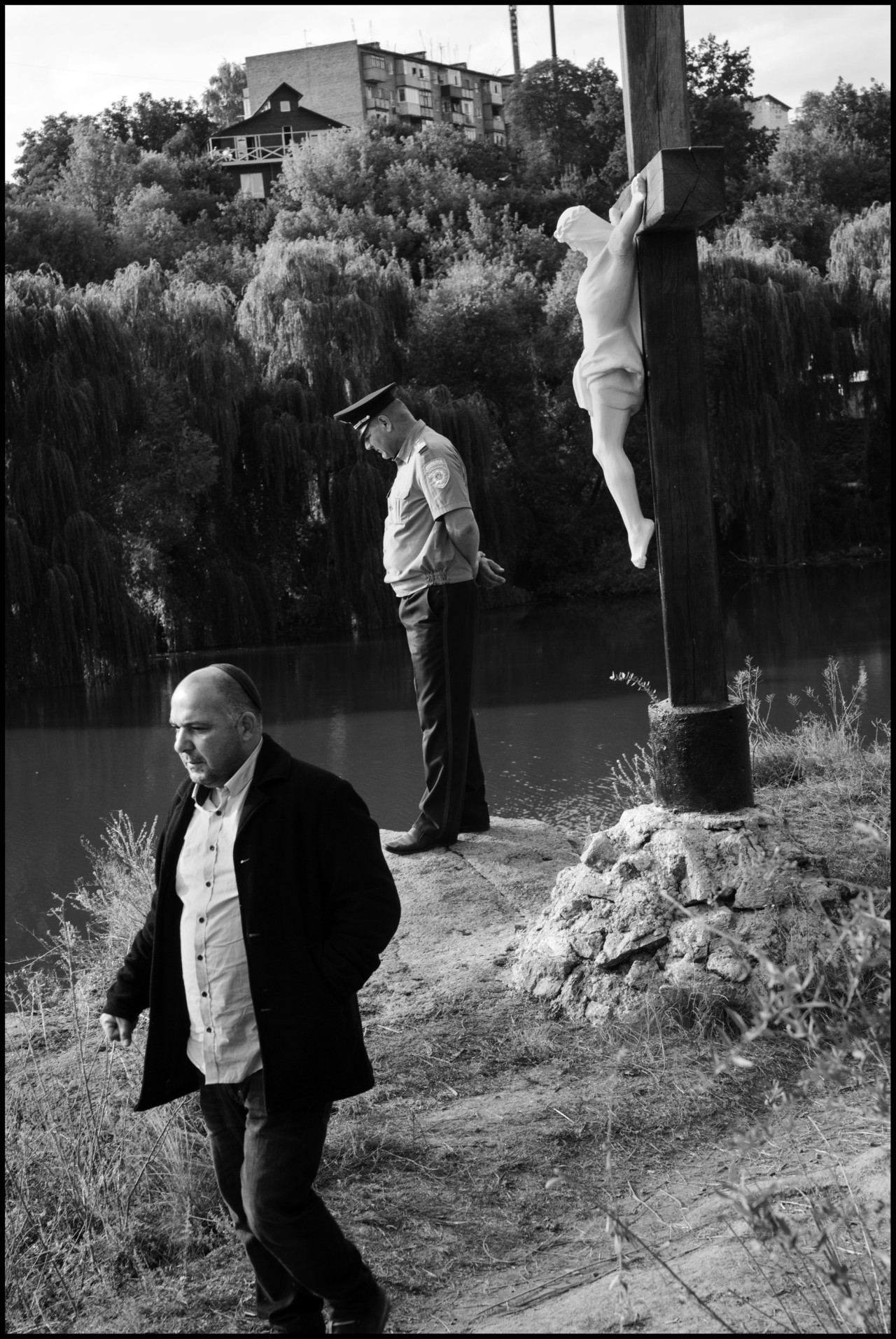

Pilgrims perform an ultimate Rosh Hashanah ritual by throwing stones in a small lake. A large cross, carrying the crucified Christ, stands above one of the banks; a crude message sent by Christians militants, who do not consider this annual gathering, this Jewish renewal, positively. The Ukrainian and Israeli police protect the cross against a potential attack. I wonder what those pilgrims think of this blatant provocation.

Many are sorry to encounter such hostility while gathering in peace. I argue that those Christians militants seem to forget that Jesus was also a Jew. I am not sure they appreciated my humor… Jewish humor!”

Patrick Zachmann

Patrick’s Zachmann’s documentation of Jewish culture began from a very personal exploration of his own, mysterious, family history. Here, he explains how he came to document Jewish rituals, which then led him to also document the pilgrimage of orthodox Jews to the Ukrainian town of Uman.

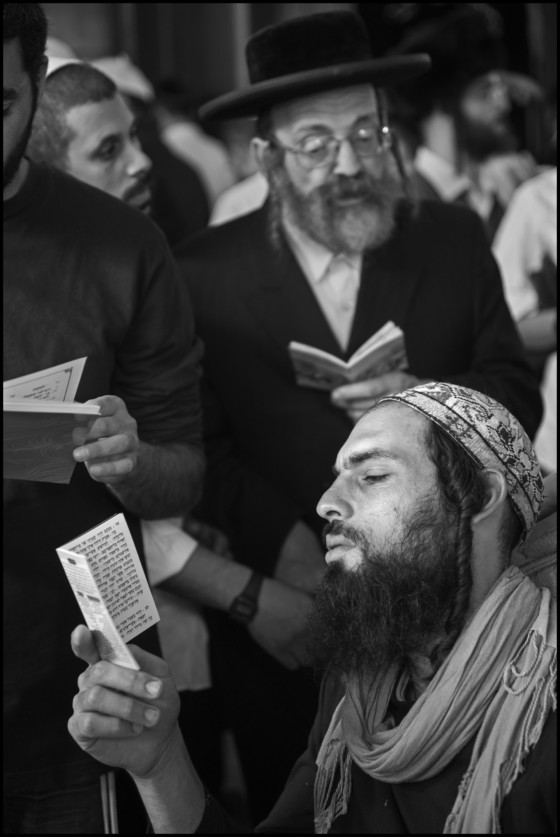

“In the early 80s I started working on a long-term project about my Jewish identity and my unspoken familial history. I began my investigation by photographing Orthodox Jews, the Lubavitch from Paris. I am neither religious nor a believer, and the figure of the Jew with a beard, a hat and a long black caftan had always seemed stereotypical to represent the whole Jewish community because this image seemed more grounded in the past than in contemporary Jewish life. In 1987, I published my book Enquête d’identité (Identity Investigation), which contained a photographic series on my own family in the last chapter.

Collecting images of unknown Jews felt like the long and necessary path to understand my own identity. In 2003, I went to Hungary, and I discovered numerous villages where a majority of Jews and Tziganes used to live. Nine hundred Jews, from the Mad village in the Tokaj region, went to Auschwitz. Only thirty came back alive and only one of them still lived in Mad. I took a few pictures of houses, formerly owned by Jews and now inhabited by Hungarians, captured images of the now abandoned Jewish cemetery, and left this haunted village with an uneasy feeling.

I decided to go back to Poland and visit different villages where, each year, hundreds of Jews reunited around other graves. And then, in front of me, images of the lost past I was looking for were displayed. Villages had, of course, changed but those Jews with a beard, hat, and long black caftans appeared unchanged, unalterable, as if they were resurrected. This was a kind of revenge memory had over reality. Being able to see and photograph those religious Jews praying their dead, drinking, singing and dancing was an overwhelming experience.

When I learnt that thousands of supporters gathered each year for a pilgrimage celebrating Rosh Hashanah, in memory of Rabbi and the wise Naham at Uman in the Ukraine, I wanted to go. This city, whose population was 40 per cent Jewish before the war, was being returned to by the Hassidim community, but also by non-Orthodox Jews, temporarily, and under the stunned, sometimes unwelcoming gaze of Uman residents.”